Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Remembrance Day, or Poppy Day as it is sometimes known, is observed every year on 11 November, or on the nearest Sunday to that date. How many people these days know what this date signifies? Over the years, many South Africans have lost sight of the significance of the term 'remembrance' in the military sense. This short article will attempt to rectify this.

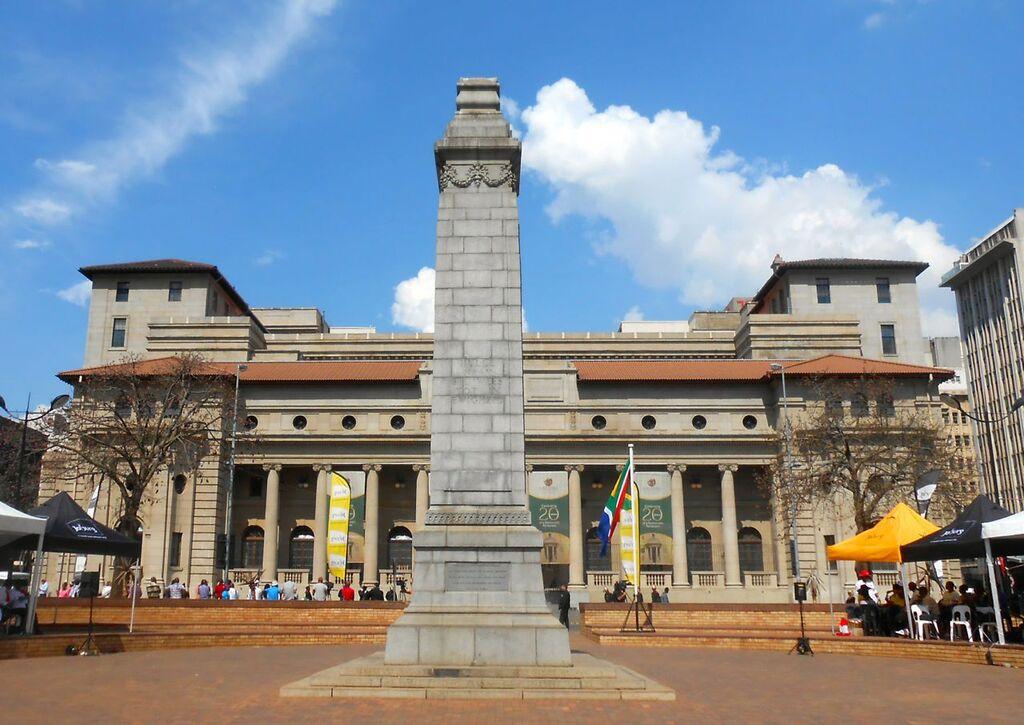

Cenotaph Johannesburg (The Heritage Portal)

In 1918, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the guns fell silent to end the First World War (1914-1918), the largest global man-made catastrophe known until that time. The 'war to end all wars' cost the lives of a total of 8 634 300 soldiers. Twenty years later, the Second World War (1939-1945) saw the loss of 24 517 000 combatants' lives. In addition to these statistics, millions of civilians died during both conflicts.

As a comparatively young country which permitted only a small segment of its population to bear arms, South Africa nevertheless made significant contributions to the Allied causes in both world wars and in the Korean War (1950-3). In the First World War, 245 419 South Africans of all races volunteered for military service; during the Second World War, 342 692 South African men and women of every race came forward; and in the Korean War, 826 men saw service with No 2 Squadron, South African Air Force while ten officers of the South African Armoured Corps served with the British Army. Will we remember them?

A scene from the Remembrance Sunday Commemorations Johannesburg 2014 (The Heritage Portal)

Ideas of silent remembrance for those who died for their country emerged around the world at the time of the First World War. The horrendous slaughter of that war and the grieving it caused sent shockwaves around the world. When the war took a turn for the worse in 1918, many areas in South Africa called for a halt of activity at midday to '...direct the minds of the people to the tremendous issues which are being fought out on the Western Front'. The Mayor of Cape Town, Sir Harry Hands, declared this policy official on 14 May 1918 and, on 14 December 1918, following the signing of the armistice in November, an impressive public display of remembrance was observed in Cape Town. At the firing of the midday gun, traffic came to a halt, all hats were raised and the public stood in silence as the Last Post and Reveille sounded through the streets.

The implementation of the 'Two Minute Silence', traditionally held throughout the British Empire (now the Commonwealth of Nations), has its roots in South Africa. There were various people around the world who felt that an official period of silent remembrance would be appropriate. In Melbourne, Australia, a plaque commemorates Edward George Honey, who, it is believed, first promoted the idea. In a letter published in the London Evening News on 8 May 1919, Honey called for a five minute silence to mark the first anniversary of the armistice, but no evidence exists to suggest that any official action was taken in this regard.

It was the proposal by Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, well-known South African philanthropist, author and politician, which was acted upon. Fitzpatrick had been deeply affected by the loss of his son, Nugent, in France in December 1917. In commemoration of the Armistice, he appealed to King George V for a two-minute pause to be observed annually throughout the Empire at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month: one minute in remembrance of the fallen in war; and one minute in gratitude for those who survived. Fitzpatrick had access to the King, who was moved by the idea. The official call of the King was published in the Sunday Times on 7 November 1919 and read as follows:

THE GLORIOUS DEAD

King's call to his people

Armistice Day Observance

Two minutes' pause from work

The King invites all his people to join him in a special celebration of the

anniversary of the cessation of war as set forth in the following message:

To all my people

Buckingham Palace

Tuesday next, November 11, is the first anniversary of the Armistice, which stayed the world-wide carnage of the four preceding years and marked the victory of Right and Freedom. I believe that my people in every part of the Empire fervently wish to perpetuate the memory of the Great Deliverance, and of those who laid down their lives to achieve it.

To afford an opportunity for the universal expression of this feeling it is my desire and hope at the hour when the armistice came into force, the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, there may be, for the brief space of two minutes, a complete suspension of all normal activities. During that time, except in rare cases where this may be impracticable, all work, all sound, and all locomotion should cease, so that, in perfect silence, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the Glorious Dead.

No elaborate organisation appears necessary. At a given signal, which can easily be arranged to suit the circumstance of each locality, I believe that we shall gladly interrupt our business and pleasure, whatever it may be, and unite in this simple service of silent remembrance.

George R I

Two months later, Fitzpatrick received the following letter from Lord Stamfordham, private secretary to the King:

Dear Sir Percy Fitzpatrick

The King, who learns that you are shortly to leave for South Africa, desires me to assure you that he ever gratefully remembers that the idea of the two minute pause on Armistice Day was due to your initiation, a suggestion which was readily adopted and carried out with heartfelt sympathy throughout the Empire.

Yours truly

Stamfordham

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, the observance of Remembrance Day has also embraced silent remembrance of all those who have died in conflict since the First World War. As South Africans unite as one nation, we should use 11 November to remember the 12 452 South African casualties suffered in the First World War, the 38 208 casualties suffered in the Second World War, and the 34 pilots killed in the Korean War. Many war graves to South Africans lie far from home, in Namibia, in France and Belgium, in Tanzania, Ethiopia, the Middle East, Italy, Korea and elsewhere. Closer to home, we should remember the many South Africans who died in the conflicts on our borders and in the Liberation Struggle of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. As yet, there are no reliable figures for these casualties, but what is important is that they all contributed to building our country as we know it today.

A veteran shows off his medals at the 2014 Remembrance Sunday Commemorations in Johannesburg

The observance of 11 November is not about celebrating any victory, nor about boasting about our achievements in conflict. It is about showing respect for those who were willing to serve their country and, if need be, to make the ultimate sacrifice so that we who are here now can have the life that we know. As the soldier's prayer states,

And when you go home tell them of us and say

For your tomorrow we gave our today

Our gift was great, but you must now give a greater gift

We died. Now you must nobly live

To complete the plan

And make man brother unto man.

In conclusion, I quote the Remembrance Prayer:

They shall not grow old

As we that are left grow old

Age shall not weary them

Nor the years condemn them

At the going down of the sun

And in the morning

WE SHALL REMEMBER THEM

Veterans at the Cenotaph

References

- Abrahams, J C, A Debt of Honour (Printed as a token of gratitude to the fallen by the South African National Defence Force, copyright 1997).

- Blake, A, Not For Ourselves (History of the South African Legion, 2004).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.