Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

During the 1980s, the Pietermaritzburg Society was dedicated to the preservation of the city’s red brick Victorian architecture. The president was architect Gordon Small who had been commissioned by the Natal Provincial Hospital Services to advise on the restoration of some of the old buildings at Fort Napier, originally the headquarters of the British garrison in Natal, but then as now, being used as a mental health facility.

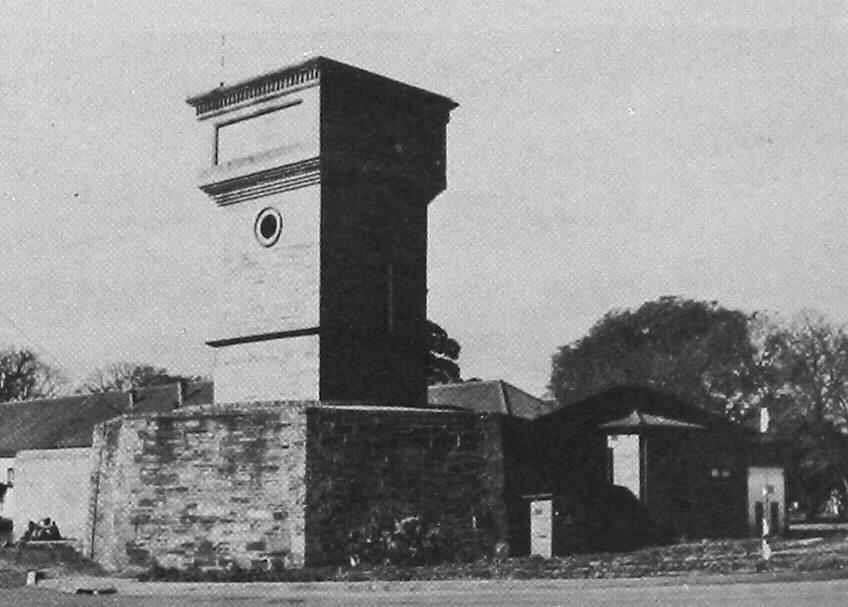

First and last structures of the fort: The turn of the 20th Century water tower built into the 1843 redoubt.

Gordon arrived at a society meeting sometime in 1987 marvelling at the wealth of heritage buildings and at the history of the old fort that lay cut off from the world by strong gates, tall trees, and the general inaccessibility of a mental health institution. Paul Thompson, a history professor at the University of Natal (who had trained at a military academy in the USA), jumped through several bureaucratic hoops, but received permission to do a survey of the surviving military buildings on the site.

There was some talk of turning some of the buildings into a museum, but this would have fallen foul of the Tri-Cameral Constitution beloved by “Die Groot Krokodil”, one PW Botha, and it would have been hijacked as a “White-Own Affair”.

My wife, Anne, was Secretary of the Society at the time and she managed to arrange for a delegation to meet Dr Fred Clarke, the Natal Provincial MEC in charge of Hospital Services who enthusiastically endorsed a heritage use for the old military buildings. Unfortunately, Fred and his colleagues were rendered politically extinct within a matter of days by the implementation of the Tri-Cameral System and the incoming nominated National Party politicians were less sympathetic. So, no museum has ever eventuated.

Far too much has been written about the British Army during all the wars in Natal, but far less was known about what the garrison got up to when not fighting Boer and Zulu foes. In fact, Fort Napier was garrisoned by the British for seventy-one years (from 1843 to 1914) making it arguably the longest occupied British garrison post in South Africa and possibly on the African continent.

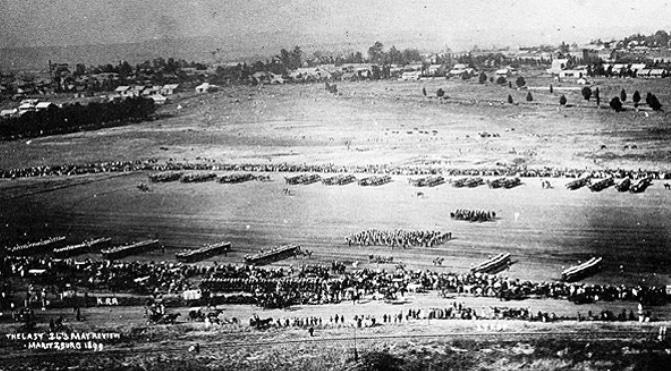

The British garrison parades shortly before the 2nd Anglo-Boer War

I decided to write my PhD as a socio-economic history of the garrison at Fort Napier, as I was determined to demonstrate that this was an African fort and its history belonged to all South Africans, not just to one racial group. I was then ambushed by Professor John Laband, co-editor of the commemorative publication being prepared for the pending 150th anniversary of the city, Pietermaritzburg 1838 - 1988: A new portrait of an African city. John ordered me to produce a piece on Fort Napier and ignored my protestations “But I don’t know anything about Fort Napier yet!”

The cover of the Pietermaritzburg 150th anniversary publication 1988

I started learning quickly and managed (with Hamish Paterson at the SA Military History Museum in Johannesburg) to produce the required text. What the exercise taught me was that I would have to do extensive research into War Office and regimental records in the United Kingdom. I was extraordinarily fortunate to be accepted as a PhD candidate by Professor Shula Marks, then Director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London.

I travelled the length and breadth of the United Kingdom from Enniskillen in Northern Ireland, to Edinburgh in Scotland, Brecon in Wales and to numerous regimental museums in England. The bulk of the research material was at the Public Records Office at Kew on the outskirts of London. I soon discovered that while many historians had used the Colonial Office records, the War Office records were largely academically unexplored. It took me more than five years to complete, submit and defend the thesis (a terrifying ordeal that took place in London on 27 April 1995, South Africa’s first Freedom Day public holiday).

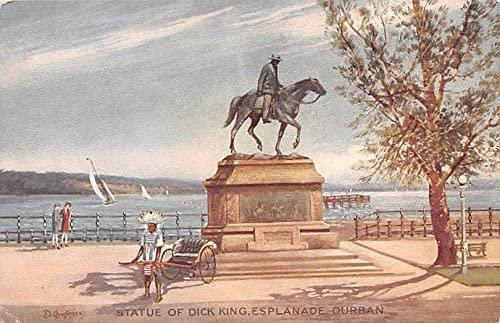

The story of Fort Napier begins in 1842 in Durban when the Boers or Trekkers clashed with a detachment of the British army under Captain Thomas Charlton Smith, and Dick King undertook his epic ride to Grahamstown to fetch reinforcements. When the reinforcements arrived and raised the siege of what is now called The Old Fort, Andries Pretorius and the Trekkers withdrew to Pietermaritzburg. The British subsequently sent a diplomat, Henry Cloete, to negotiate with the Volksraad and cement British control over what would eventually become the Colony of Natal.

Old postcard of the Dick King Memorial

Smith refused to send troops to protect Cloete on his mission to the Trekker capital, so off he went alone. His negotiations were successful, and the Drakensberg were agreed upon as the edge of British control. Those irreconcilables among the Boers retreated to the mountains. While Cloete was writing his report to the Governor in Cape Town, he was confronted by a rowdy deputation of Boer women, led by Susanna Catherina Smit (wife of a preacher and a sister of Gert Maritz). The delegation declared that they had suffered alongside their menfolk and demanded to be heard. Susanna Smit declaimed in ringing tones that she “would walk out by the Draaksberg barefooted, to die in freedom, as death was dearer to them than the loss of liberty”. Cloete was appalled and informed the delegation that they were presuming upon liberties that no married women were entitled to claim. The defiance of the women has been commemorated by the statue of “Die Kaalvoet Vrou” standing in the mountains near the Oliviershoek Pass between Bergville and Harrismith. Sadly, poor old Susanna Smit lived out her life and died in Pietermaritzburg under the Union Jack.

Kaalvoet Vrou (Image: Petronel Fourie)

Rather rattled, Cloete demanded that Smith send troops up to Pietermaritzburg claiming (rather disingenuously) that this could be accomplished “with as much security as through any part of Her Majesty's dominions”. Reluctantly Smith despatched Captain Kyle and two companies of the 45th Regiment (later known as the Sherwood Foresters) together with a detachment of Royal Engineers under the young Lieutenant CJ [Charles] Gibb, a troop of the Cape Mounted Riflemen (or Cape Corps whose skilled Khoisan mounted soldiery were known affectionately but derogatorily by the British troops as the “Totties”) and all the assorted hangers-on needed to drive the waggons, manage the baggage and herd the cattle. Those soldiers who had been allowed to marry were accompanied by their wives and children. So, the British military occupation of Natal and the construction of Fort Napier was never purely a white, let alone a white male affair.

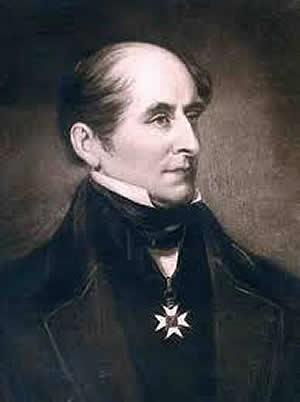

On 1 September 1843, the new garrison marched through the dusty streets of the Voortrekker town with the regimental fifes and drums playing Major Smith's favourite Irish marching tunes such as “Garry Owen” and “The Sprig of Shillagh”. Lt Gibb identified the hill at the western end overlooking the long streets of the Trekker town as the site for their camp. The drums rolled, the fifes squealed, and the officers saluted as the Union Jack was raised and Fort Napier was proclaimed into existence. The fort-to-be was named in honour of Sir George Napier, the Governor of the Cape, who had sent the troops to Natal. Cloete reported to Cape Town with some satisfaction, that “The British flag is now displayed as an emblem of peace and security”.

Portrait of George Thomas Napier

While this remark reeks of imperialist complacency, what is significant about the British occupation of the Colony of Natal (south of the Thukela River) is that it could be said to have begun as a relatively benign presence (however things may have developed over time). The Zulu King Mpande supported it, and, in many ways, the new colony was a safe haven for many refugees and other groups. The guns of Fort Napier were never fired in anger, but the fort did serve as a place of refugee during various crises (including for members of the Zulu royal family). However, from the 1870s it served as a base for more aggressive and assertive actions such as the clash with Chief Langalibalele and of course the major thrusts against the Zulu Kingdom and the Transvaal Republic.

Langalibalele

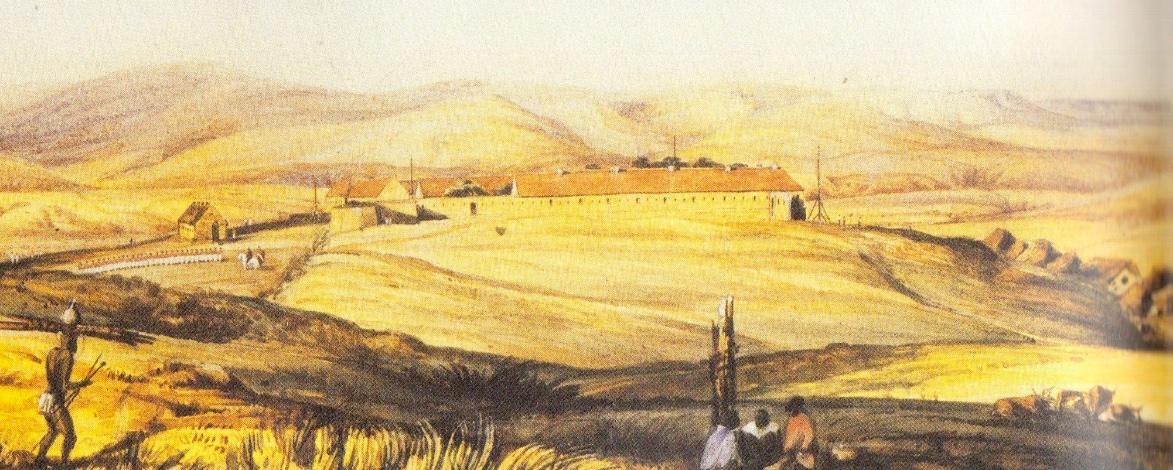

On 1st September 1843, Gibb began the construction of the fort, which was the first major building project in the city, and it took more than two years to complete. The Trekkers had only built a few simple domestic dwellings during their rule so Fort Napier was the first major public work in Natal.

Gibb began with the erection of two redoubts at opposite ends of the barrack square for the placing of artillery pieces, carefully sited to cover the town, the river crossing below the fort that marked the end of the road from Port Natal and the road to the interior that wound up Town Hill to the Midlands. The soldiers did the manual labour: digging the foundations, siting the artillery positions, and knocking loopholes through the walls, shaping stones, carving wooden beams from the yellowwood trees on the hills in the vicinity and establishing a modest, but nevertheless imposing fort with the original quadrangle largely built of stone. Many of the later additions were made of Pietermaritzburg’s famous red brick.

In 1991, the Natal Provincial Administration reroofed Ward A of the Fort Napier Mental Hospital and the original yellow-wood roof beams were exposed still showing the marks of hand-sawing and the wooden pegs and handmade nails which were used to secure the beams. So much for a temporary structure.

The reports on the construction of the fort in the War Office archives, cover issues such as construction costs (a bitterly contentious issue with the Treasury), the exploitation of natural resources, the use of troops as labourers and the early employment of African labour in a developing urban environment. They also give a completely different angle on early Natal colonial history. The standard definitive history of Natal by professors Edgar Brookes and Colin Webb (A History of Natal, 1965) firmly declares that by 1845, Natal can be regarded as a permanent British colony. The War Office records show that no firm decision was ever taken to make Fort Napier a permanent post because of the dithering of the Colonial Office as to the permanence of the colony.

Therefore, Fort Napier was constructed as, and classified as, a “field operation” structure, in other words it was temporary, but it stayed and grew and defined much of cultural character of settler Natal. Most historians of the colony of Natal record that the British garrison brought organised sport to the city (rugby, cricket, polo, football, etc). Also, many cultural organisations were originally established by the garrison: The Natal Society (on the model of an English Learned Society) out of which grew the amateur dramatic society, the library and later, the Natal Museum. The garrison was seen as a benign and positive influence.

A recent photo of the Natal Museum (The Heritage Portal)

The garrison also imported the British system of class distinction with the officers living out of barracks in what became the posher area of the city and the troops living in barracks. John Robinson, editor of Durban’s Natal Mercury, and later the colony’s first Prime Minister, wrote: “Maritzburg is the most clique-ridden town it has been my lot to dwell in!”

The garrison, and its band, hosted frequent balls, dances and performances in public spaces. Settler mothers used these occasions to aim their daughters at eligible young officers. These intrigues were satirised thus by the Durban newspaper Times of Natal:

Mamma: “Now miss, have you written down the distinctions of rank as I told you?”

Alice: “Yes, Ma”

Mamma: “Very well, then, recollect you've no excuse this time; and if I catch you dancing with anyone below a captain, you don't go out for a month!”

Tom Sharpe, the writer whose name became famous with Oxbridge satires such as Porterhouse Blue, cut his teeth as an anti-apartheid activist in Pietermaritzburg. He was expelled from the country by Dr Verwoerd in the early 1960s and, in revenge, pilloried the city (barely disguised as Piemburg and Fort Napier as Fort Rapier) in his debut novel Riotous Assembly (published in 1971):

In the town itself the streets were prickly with waxed moustaches. Blanco and brass polish stood high on the list of life's necessities. In the Imperial Hotel the mornings and afternoons were liquid among potted plants and wicker chairs with the music of a Palm court orchestra. Sam Browne belts and whalebone waist pinchers restrained the officers and their wives who listened to the whine of the violins and recalled the shires and parishes of England with thankful melancholy. Many would never return and those who stayed and were not buried in the military cemetery in Fort Rapier would build their houses as close to the Governor's mansion as their seniority and overdrafts allowed.

While the garrison stayed, Piemburg prospered. Piemburg was even, briefly, gay. The Garrison Theatre was made brilliant by performances of plays and revues that bred one great English actor and playwright and charmed the Governor and his wife. Bazaars and garden parties were bright with the parasols and bustles of wives who had been swept from the terraced suburbs and semi-detached houses of South London to the grandeur of the lawns and shrubberies of Piemburg by the surprising good fortune of having married husbands whose mediocrity won for them the reward of being posted to this distant sliver of the empire. The taste of the Victorian lower middle class imposed itself indelibly on Piemburg and has stayed there to this day.

The pub culture of Maritzburg developed around the garrison and until late in the 20th Century, popular student watering holes could trace their origins back to taverns established for the troops. Prostitution in the city was also driven by the presence of young soldiers without partners. The isolation of the garrison in the early years and the lack of amenities bred ill-discipline and drunken misconduct offences were frequent. This has tended to be glossed over by other historians and, while overall the troops at Fort Napier were well disciplined and popular with the city’s inhabitants (of all races), there were some standout incidents of ill-discipline or worse.

Two examples will suffice: In the late 1840s, some of the men of the CMR attempted to desert and one of those captured was sentenced to death by execution at Fort Napier. In October 1887, a serious incident occurred when the Inniskilling Fusiliers (the old 27th Regiment) was in garrison. A brawl broke out in the barracks on a Sunday evening, one soldier was killed, and the alleged perpetrators stormed out of the gates of the fort spreading mayhem in the city. They roamed the streets trying to break into closed taverns, attacking churchgoers, and even killed a military policeman who tried to stop them single-handed. They fled down the road to Durban where they passed out in drunken stupors and were pointed out to the pursuing policy and cavalry by African wagon drivers.

The army tried to hush things up, but since there had been chaos in the city streets and civilians had been assaulted and a murder had occurred, there was an enquiry in the colonial courts. There was evidence that the cause of the brawl in the fort could have been political as the Inniskilling Fusiliers were an Irish regiment and some of the insults shouted by the mutineers were Fenian slogans. One shout recorded was “I’ll rip and roast the Queen.” It was clearly more than a drunken brawl because the General Officer Commanding, based in Cape Town, arrived in Natal on the next ship. He transferred the regiment out of South Africa within weeks and the officer commanding was quietly cashiered.

By the time the Second Anglo-Boer War (or South African War) broke out in 1899, most of the British garrison was redeployed on the borders of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Fort Napier remained a regional headquarters and supply depot. Refugees from the Witwatersrand were housed there and later Boer women and children whose farms had been burned down were given accommodation there. One young boy grew up to be General Dan Pienaar, a famous commander in the Union’s Army during World War 2. He never forgot the kindness with which he was treated by the British tommies at the fort.

After the war, the garrison was reduced to a few details of the Royal Garrison Regiment, a third-grade unit composed of men on the verge of pension. It was known as the Royal Dugouts. Since the 1880s the withdrawal of the garrison had been a burning issue in Natal colonial politics; the imperial government wanting to withdraw the troops as an economy measure and the colonial government and the people of Pietermaritzburg desperate to retain the troops for economic, political and prestige reasons. So, in 1902, the Royal Dugouts were left at Fort Napier as a sop to the colonial government. Many of the buildings of the fort were crumbling around them.

In 1906 the Bambatha Rising took place and Natal went into a complete panic and over-reaction. Colonial forces were mobilised to put down the rebellion and the imperial government (with a young Winston Churchill as a responsible junior minister) ordered a battalion of the Cameron Highlanders to Fort Napier to provide backup. Once more bagpipes skirled and parades and dances were held. Fort Napier came back to life. However, the imperial troops were not deployed in the field as the British government (and the Transvaal Government under General Louis Botha) strongly disapproved of Natal’s ham-fisted and repressive approach to putting down the rebellion.

Given the dilapidation of some of the buildings at Fort Napier, some of the temporary structures at the base in Middelburg in the Eastern Transvaal were transported to Pietermaritzburg. A magnificent, corrugated iron officers mess building was constructed at the highest point of the fort, overlooking the river. The settlers were enchanted with the new venue for dances and social gatherings. The structure is a slightly grander version of the Smuts House in Irene, that was also sourced from the camp in Middelburg. Both buildings were prefabricated in Britain, taken to India where they performed sterling service at a British military base. Then they were shipped to South Africa in the latter days of the Anglo-Boer War and within South Africa they moved from Middelburg to the Smuts farm (in the first instance) and to Fort Napier in Natal in the second.

Photographs of the Officers Mess Building (via AngloBoerWar.com)

Smuts House (The Heritage Portal)

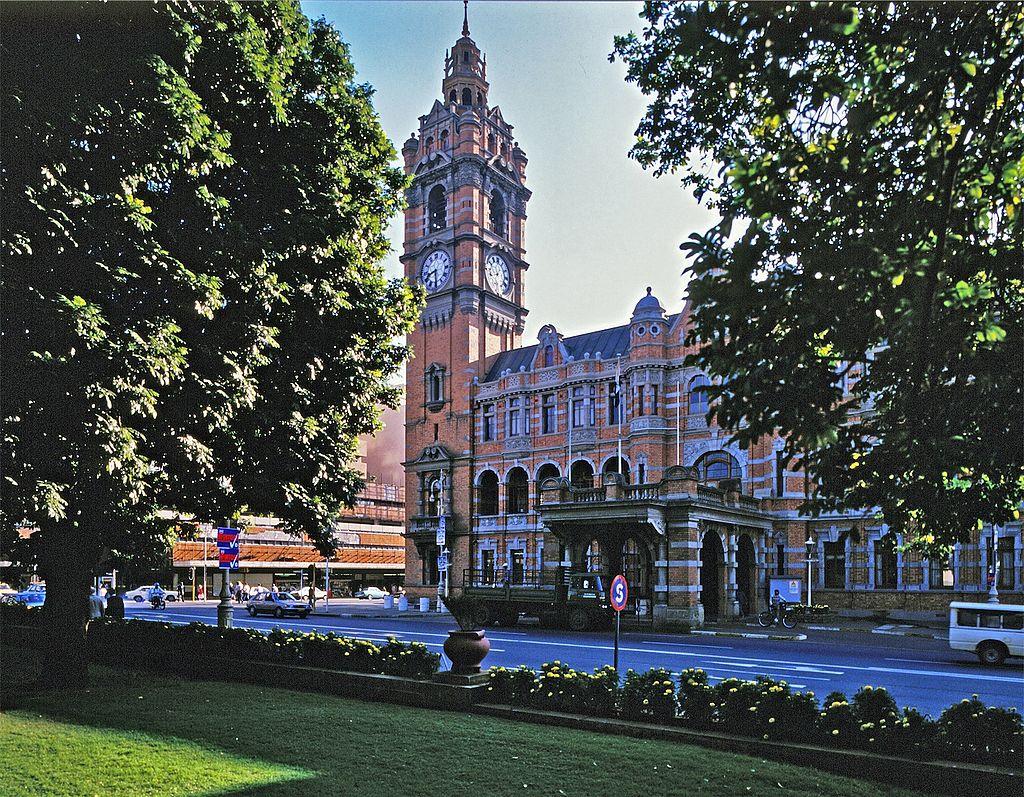

The garrison remained at Fort Napier after the establishment of the Union of South Africa. It was left as a security blanket for the pro-British settlers, still uncertain about their role in the new largely Afrikaner-dominated Union. So, for a while, the band played on. However, in 1914, the outbreak of the First World War resulted in the immediate withdrawal of the remaining British troops across South Africa. The South Staffordshire Regiment was at Fort Napier when the orders for embarkation arrived. There was a week of frantic activity, the Natal Witness reported on the auction of soldiers’ assets; there was a last patriotic concert in the City Hall addressed by the regimental colonel, the mayor, and the new provincial administrator. The regimental band, dressed in field khaki, not parade ground red, beat the retreat in front of the City Hall for the last time. The actual date of departure was a military secret, but as the troops boarded the train to take them to Durban and to the slaughter of the Western Front in France, a young officer ran across the road to Wykeham Girls School and disrupted the mealtime so that; the girls could run to the railway line and wave the train goodbye.

Pietermaritzburg City Hall (Janek Szymanowski via Wikipedia)

The fort did not remain empty for long as the Union Government decided to use it for the internment of enemy aliens for the duration of World War I. So, it filled up with Germans, Austrians, Hungarians and even the occasional Turkish citizen. South Africans of German origin were swept up in the net as well, one of the most prominent being the scientist Dr Hans Merensky who found detention a severe physical and mental challenge. Apparently while he paced around the old fort, he worked out in his mind a theory that enabled him to locate diamonds off the Cape West Coast in the post-war period.

In the 1920s, after the usual bureaucratic squabbles over the disposal of British military assets in the Union, Fort Napier became a mental health facility and remains so to this day.

To return to one of the key investigations I made, Fort Napier may not have had to withstand a siege, or form a key strong point a battle line, but it had a profound effect on the economic and social development of Pietermaritzburg. In the early days, wages of the soldiers introduced the first measurable amounts of currency into the financial system. The soldiers not only built the fort itself, but they worked with the civilians in constructing the infrastructure of the city from domestic homes to schools and much more. Many soldiers took their discharges in Pietermaritzburg and settled in Natal (until the joined the diamond and gold rushes). They married young local women and caused local scandals. The cultural character of colonial and even post-colonial Natal was set in no small measure by the lengthy presence of the garrison at Fort Napier.

Among the famous visitors to the fort were Queen Victoria’s son, Prince Alfred, Eugene Louis Napoleon, the French Prince Imperial, young Winston Churchill and numerous writers and literary figures.

Above all, this was not a “white” endeavour. There were the so-called coloured troops of the Cape Mounted Riflemen and Natal Africans were recruited into the British army to act as auxiliaries during the Anglo-Zulu and Anglo-Boer wars. The Christian amaKholwa community of Edendale (which provided some the earliest leaders of the ANC) was closely associated with the garrison. The fort was the nearest market for produce grown and sold by the Kholwa. The educated members of the community acted as translators and interpreters and the troops of the garrison often paraded and manoeuvred in the areas around the mission settlements in the Edendale valley.

Today, the hospital still operates out of the fort, the oldest buildings still have a limited function, and the military cemetery is immaculately maintained (although the inscriptions on some of the oldest graves have been worn away). My favourite tombstone is of a regimental farrier who died in the execution of his duties through being kicked by a horse.

So let us spare a thought for one of the longest lasting and most peaceful military structures in the country on its 180th anniversary.

Fort Napier, Pietermaritzburg 1843 – 2023 A museum that never was: A personal reflection on a 180-year-old “temporary” structure.

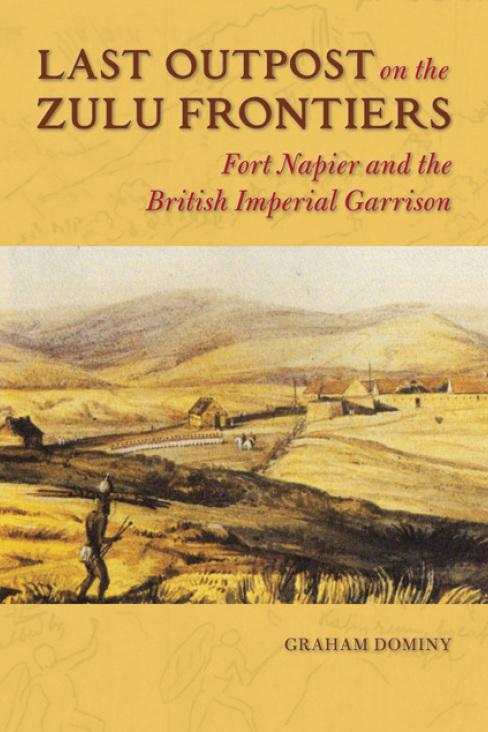

Dr Graham Dominy is a former National Archivist of South Africa and is also an historian and author. He is the author of Last Outpost on the Zulu Frontier: Fort Napier and the British Imperial Garrison (University of Illinois Press, 2016). He currently serves as a member of the National Heritage Council.

Book Cover

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.