Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

As the war persisted into late 1900, the British intensified their attempts to cut off local support for the Boer guerrilla forces. Farms suspected of harbouring Boer commandos were burned and crops and livestock destroyed, and the intensification of the scorched earth policy precipitated the biggest battle in the Magaliesberg campaign and an overwhelming Boer victory.

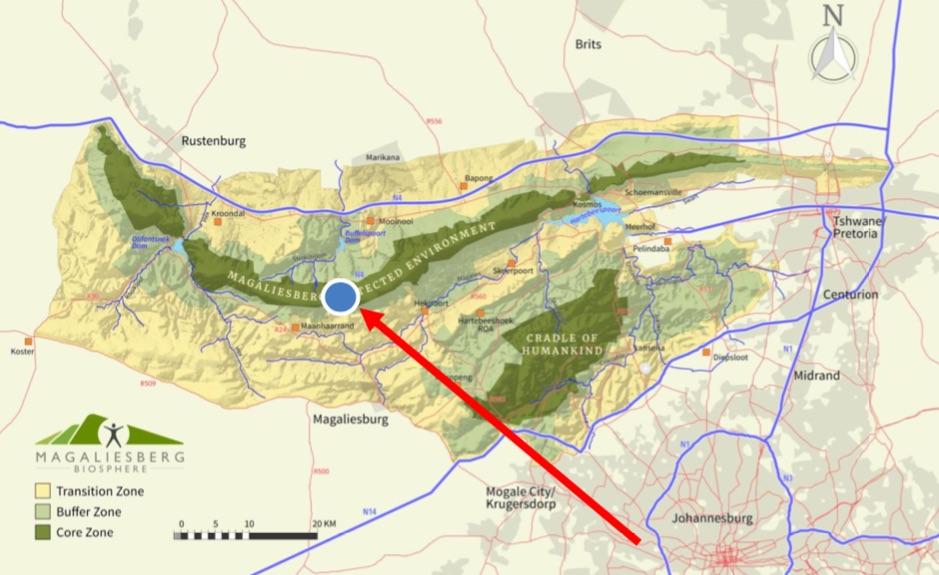

Location of the Battle of Nooitgedacht in the Magaliesberg Biosphere Reserve

A force of about 1500 men, nine guns and more than 100 wagons under the command of General R.A.P. Clements had been plundering the Magaliesberg valley since October 1900. On 8 December Clements was warned of a large Boer presence in the area and, while he waited for reinforcements from Krugersdorp the column camped on the farm Nooitgedacht at the foot of the highest cliffs in the range. A steep gulley gave access to the top of the mountain where Clements posted a signalling corps and picket guards of about 150 men on either side of the gulley.

Looking up at the high cliffs (The Heritage Portal)

From hidden observation posts De la Rey and Smuts watched the establishment of the camp. The isolated pickets on the cliffs could easily be overcome leaving the camp completely vulnerable. General Christiaan Beyers, De la Rey’s counterpart in the northern Transvaal, was approaching Bethanie with another 1500 men. The addition of these gave the Boers a strength twice that of Clements’s column and with this advantage they could be confident of victory.

Between the two Boer detachments, however, Broadwood’s cavalry was encamped near Kromrivier and his intelligence had informed him of Beyers’s presence in the area. Beyers solved the problem by letting it be known among the local people that he was intending to attack Rustenburg; within twelve hours the disinformation had reached Broadwood and he led his column westwards to protect the town. However, he neglected to pass on to Clements his knowledge of the new Boer arrivals and so contributed to the eventual British disaster.

Soon after dawn the pickets posted on the summit were overpowered by the Boer commandos. (H.H. Wilson From After Pretoria: The Guerrilla War)

Beyers and De la Rey met on 12 December and the combined attack was put in motion. Operating from a base on the Breedtsnek road, two of Beyers’s commandos under Commandants Van Staden and Krause climbed up the northern slope to capture the pickets on the western buttress of the Nooitgedacht cliffs. Another pair of commandos, under Commandants Kemp and Marais, took the eastern buttress while a fifth, under Commandant Badenhorst, moved along the southern base of the cliffs and attacked a mounted infantry camp posted outside Clements’s main camp. The rest of Beyers’s force remained at their base in anticipation of the possible return of Broadwood from Rustenburg.

De la Rey in the meantime led his men against the main British camp in the Moot while Smuts moved to the south-east to cut off Clements’s line of retreat. The attack started before dawn. At the base of the cliff Badenhorst’s commando was repulsed by the mounted infantry outpost on what is now African Hills Safari Lodge. In a fierce battle the British commander of the outpost, Colonel N. Legge, was killed. On top of the mountain Beyers’s men were wavering in the face of volleys of fire from the entrenched pickets. However, in Deneys Reitz’s account of the battle, “the troops facing us on the mountain now made a mistake ...when they saw Badenhorst’s men retire in confusion they set up loud shouts of triumph. Stung by their cries our whole force, on some sudden impulse started to our feet and went pouring forward, shouting and yelling, men dropping freely as we went. Almost before we knew it we were swarming over the walls shooting and clubbing in hand to hand conflict.”

Most of the draft animals had been shot by the Boers on the summit so the men were ordered to manhandle the guns to safety. (H.H. Wilson From After Pretoria: The Guerrilla War)

By 7:00 the Boers were in control of the summit and fired relentlessly into the camp below. British soldiers scattered in disarray. Clements ordered a detachment of Cameron Highlanders to climb the narrow path up to re-take the summit, but they were mercilessly shot down. Sergeant Donald Farmer won a Victoria Cross for carrying a wounded officer to safety on that treacherous path.

Uncharacteristically, De la Rey withheld his attack on the main camp for some time, explaining later that he had awaited confirmation of Beyers’s success before attacking. The delay allowed Clements to regain control of his panicking men and organise a disciplined retreat.

While the Boers were looting and celebrating their victory, Clements was able to conduct an orderly retreat and to direct artillery fire back into the camp he had vacated. (H.H. Wilson From After Pretoria: The Guerrilla War)

Smuts, too, was tardy in closing off the British retreat so that Clements, having been unwise in his choice of campsite, now demonstrated very competent leadership. Despite the initial chaos of the surprise attack, he calmly led his stricken column to a small hill called Vaalkop (Yeomanry Hill to the British) to the south-east. Here he was able to stage a rearguard action that prevented Smuts from inflicting any damage.

At the evacuated campsite the Boers were indulging in what Smuts later described as “pandemonium in which psalm-singing, looting and general hilarity mingled with explosions of bullets and bombs” the latter emanating from the burning ammunition wagons. Clements was able to retreat leaving more than a third of his men dead, wounded or captured.

For more than 50 years those who fell at Nooitgedacht rested in quiet cemeteries, one at the foot of the magnificent cliffs, two on the summit and one at Vaalkop. They were tended by the Jennings, Sanders and Hinds families, the owners of Nooitgedacht. In her unpublished story of the farm, Muriel Sanders tells of Lieutenant Mudge, buried with his comrades on the summit: “Each year regularly ... a sprig of heather from the family garden at ‘Sydney’, Plympton, would be sent out at Christmas time to be placed on his grave.” In 1965 vandals desecrated the graves. As a result, the British Forces Committee of the South African War Graves Board arranged for the remains of the graves to be exhumed and re-interred in the Garden of Remembrance at Krugersdorp. A small monument erected by General Clements still stands at the old cemetery below the nek. A plaque has been added to it explaining the whereabouts of the other graves. The only grave that remains undisturbed is that of a Boer scout, Veldkornet T. van Zyl. Other Boer casualties of the Battle of Nooitgedacht are buried at Breedtsnek.

Fortifications on the summit of the Nooitgedacht battlefield (The Heritage Portal)

The date of 16 December is sacred to Afrikaners in commemoration of their defeat of the Zulu in 1838. It was also the day on which they had re-declared their independence at Paardekraal near Krugersdorp in 1880. To celebrate the day and their victory at Nooitgedacht, Beyers, De la Rey and Smuts led their men south-west of the battlefield to the farm Naauwpoort, which belonged to Commandant Steenkamp of the Rustenburg commando. The farm stood high on the Witwatersrand ridge with a magnificent view across the Moot to Olifantsnek.

In addition to fighting commandos, women and children arrived from farms throughout the region to share in the occasion. Each general spoke at length, calling upon those present to reaffirm their oath to observe the day as a sabbath. Then each person carried a stone to the summit of the hill and placed it on a cairn, just as had happened at Paardekraal 20 years before. The Reverend A.P. Kriel delivered a prayer of thanksgiving and proclaimed the name of the site Ebenhaezer, “stone of our salvation”. The cairn remains to this day and is now surmounted by a monument which was erected in 1958.

The following day the Boer force moved back towards Hekpoort. Clements’s column, reinforced to more than twice its original size, chose that day to return to avenge its earlier humiliation. At the same time General French bore down on Hekpoort from the south with a similar-sized force from Krugersdorp. In the face of these overwhelming odds, the three Boer generals split up and retreated separately to the west. For two months the British pursued them and minor engagements took place, although seldom with any serious outcome. By February 1901, De la Rey had established a well-concealed base in the Swartruggens, Smuts was operating in the Gatsrand near Klerksdorp and Beyers had returned to the northern Transvaal.

The Ebenhaezer monument as it is today. The original stone cairn is contained in the inner circle. (Vincent Carruthers)

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

Further Reading on the Battle of Nooitgedacht

- Amery, L.S., ed. The Times History of the War in South Africa. London: Sampson Low: 1907. Spies, S.B. & Nattrass G., eds. Jan Smuts: Memoirs of the Boer War. Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg, 1994.

- Wilson, H.H., After Pretoria The Guerrilla War. London: Amalgamated Press, 1902.

- Wedepohl, A., The Battle of Nooitgedacht, 13 December 1900. The author. Available from: Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

- Wulfsohn, L., Rustenburg at War. Rustenburg: The author, Rustenburg. 1987 revised 1992.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.