Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

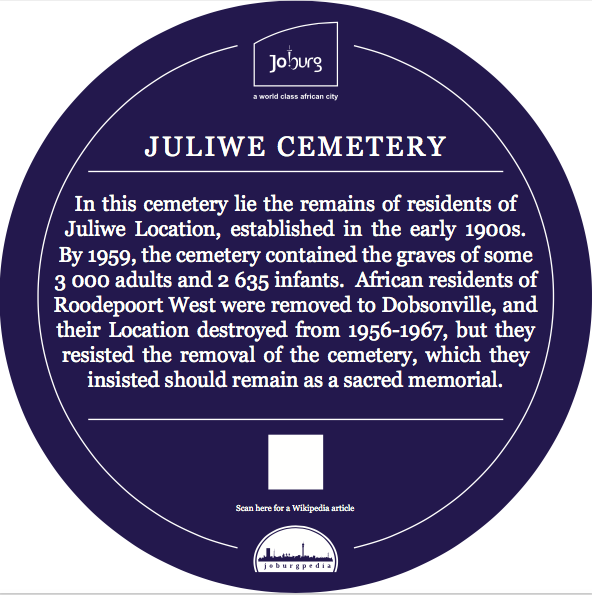

Below are notes prepared by the heritage team from the City of Johannesburg for a speech delivered at the unveiling ceremony of a blue plaque for Juliwe Cemetery during Heritage Month 2017. The speech was read out by Mr Kepi Madumo, Executive Director for Community Development, on behalf of the MMC. The notes tell the story of the forced removals of the African community from Roodepoort West to Dobsonville and the fight to save the cemetery from destruction. Click here to download a detailed history of the Roodepoort-Maraisburg Location, compiled by a team from the Wits History Workshop led by the late Prof Phil Bonner.

MMC: Community Development, Clr. Nonhlanhla Sifumba, officiating at the plaque unveiling ceremony (City of Johannesburg)

Today as we mark heritage month, we take the opportunity to recognize a community who were not only evicted from their homes in Roodepoort West, but also forced to leave behind the graves of their loved ones.

The destruction of such communities as Sophiatown and District Six have become well-known, and these names have become by-words for mass eviction. And we are honoured today to have members of the legendary Sophiatown community joining us in solidarity today.

Yet around the country, many other victims of forced removal have been largely forgotten and unknown to the wider public. The destruction of Juliwe Township, from the same time-period as the destruction of Sophiatown, is one such case of neglected history, and it is that story of 50-plus years ago from Roodepoort West which we are sharing today.

The beginnings of the Roodepoort-Maraisburg location go back to the early 1900s. The location soon became known as Juliwe, with many of its first residents coming from the local mines. In the words of the Greater Dobsonville Heritage Foundation:

“Juliwe was established as a cheap labour reservoir for the growth of industries in the Roodepoort area. Our ancestors who were housed in pitiful conditions, were able, through hard work and organization, to form themselves into a vibrant and well-structured community”.

Starting in the late 1950s, African residents of Roodepoort West were removed to Dobsonville, and by 1967 their location was destroyed. By the mid-1960s, the population of the old location had been reduced to a fraction of its size, and the few remaining buildings reduced to ruins.

In January 1963 an article appeared in The World, with vivid descriptions of the ghost town:

‘At the moment, the condition of the location is appalling. Grass is growing on the footpaths, and the remaining houses are surrounded by the debris of demolished houses … Since the mass removal of the residents to Dobsonville last year [1962], the Old Location, as it is popularly called, has fallen terribly down in communal amenities. From a distance it looks like a bombed town after an air attack”.

In negotiations over the removal of the residents of Juliwe to the new township of Dobsonville in the late 1950s and 1960s, the future of the cemetery became the most contentious issue.

Residents were firm, steadfast and determined in resisting the removal of the cemetery, which they insisted should remain as a sacred memorial.

The cemetery was located on the west side of the location, with a large cattle kraal located nearby. A report from 1959 records 2 000 adult graves in which 3 000 bodies had been buried, along with 2 635 infant graves.

As the last resting place for the population of Juliwe, the cemetery played a great role in cultural, community and religious life. The old cemetery was the focus of much ritual activity – a place where both Christian and African ancestral rites were carried out.

Ex-residents remember the generosity of Rev. Maake, who headed the Zionist or Ethiopian African Anglican Church. Rev. Maake owned a flourishing business selling coal and firewood, and offered a mule and cart free to carry coffins to the gravesite. If the family were unable to afford the undertakers, Rev. Maake’s cart would carry the deceased.

Funerals were a key moment for expressing public solidarity and family grief. On the day of the funeral, ministers from different churches would come, and all church denominations would unite. Different ethnic groups would unite in solidarity, with Xhosa people catering for Tswana tastes, and vice versa. Cooking ‘Mnqusho” (samp), for example.

The planned removal of the cemetery, like the removal of the Old Location, was never consulted with the people who would be affected on a most personal level. By June 1968, the Council resolved to take immediate steps to close the cemetery.

Once the cemetery was closed, residents of Juliwe first heard rumours of the proposed sale of their cemetery to the Horizon Development Company, and the possible exhumation of the bodies of their dead, which would then be re-interred in a mass grave.

The response of the residents was one of indignation at the removal of the cemetery. The Town Clerk was warned of growing anger and resentment among residents, with the Advisory Board urging that the cemetery was held sacred by residents and should be left intact.

Should the Council go ahead with the destruction of the cemetery, the Advisory Board warned that the consequences would be dire:

“We would respectfully urge that unless such assurance is given by the Council, [that the cemetery would remain], a grave and permanent sense of injustice and wrong would be bred, that would pass from generation to generation and would never be forgotten”.

Faced with these pressures, the Roodepoort-Maraisburg Town Council finally decided against removing the cemetery.

With the rest of Juliwe Location having been erased by the development of a whites-only township, only the cemetery remains as a stark reminder of a community which was uprooted, now surrounded on all sides by suburban homes.

Residents were spared at least the removal of the cemetery, as the graves were not bulldozed. Yet, the victory had more than a touch of bitterness, as residents of Dobsonville could not visit the graves of their ancestors for as long as they were kept away by the Group Areas Act.

Today, we have placed a heritage plaque as a mark of respect at Juliwe Cemetery, to help keep alive a memory which should endure for all generations.

Let me close by quoting once again the words of the Greater Dobsonville Heritage Foundation:

“We remember our ancestors with pride and admiration for their sacrifices and dedication, so as to be able to raise us, their descendants, to be upright citizens of the country of our birth”.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.