Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

I had completed cataloguing the Schrire’s collection of about 650 maps and sea charts about nine months ago. Then, last week, the family came across a roll of twenty-five maps at the back of a cupboard, while they were packing to move into a smaller house.

‘We probably set them aside because they needed some repairs.’ Well, we repair old maps.’ ‘Would you look at them?’ ‘What a question!’

Ten of the maps were gems. One was a bit of a mystery too.

The mystery map

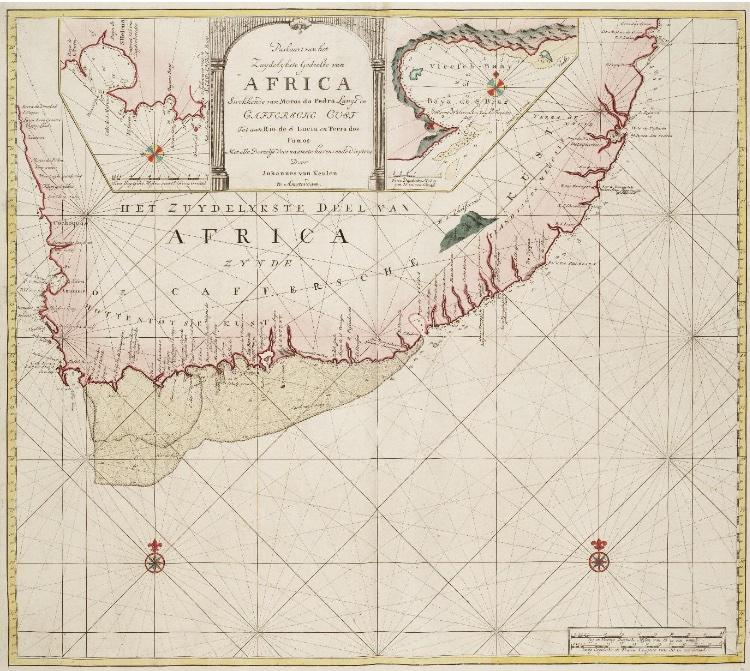

The map (see main image or click here for a high resolution version) is titled ‘Paskaart van het Zuydelykste Gedeelte van Africa … Met alle Desselfs Voornaamste havens ende dieptens Door Johannes Van Keulen te Amsterdam’ (Map of the Southernmost Part of Africa … with all its principal harbours and depths by Johannes Van Keulen in Amsterdam). It is quite large (58.5 x 50 cm) and certainly needed restoration. The map had been applied to a sheet of stabilizing backing paper: paper moths and their hungry larvae had been attracted to the map. The backing paper was coming loose, needed to be removed and replaced with thin archival tissue paper to restabilize the weakened paper of the page with the map

The map with its red-coloured coastline is is also aesthetically attractive. There are two inset maps, one of St. Helena Bay and one of Vleesch Baay [now Vleesbaai], with an alternative Portuguese name: Bay de San Bras. The latter is the early Portuguese name of Mossel Bay to the north-east of Vleeschbaai. This naming error was introduced in 1652 by Jodocus Hondius III on his chart ‘Paskaart van de Zuyd-west-kust van Africa’ [Chart of the south-west coast of Africa]. His map was included in Hondius’s 'Klare beskryving van Cabo de Bona Esperança' [A clear description of the Cape of Good Hope], published when the Dutch settled at the Cape.

The lines of latitude and longitude intersect on the map at right angles, which means that the chart is drawn on Mercator’s Projection. The Agulhas Bank is prominently displayed. The placenames are in either Portuguese or Dutch. Van Keulen assigns the name M.S. Christoval (Montes São Christoval, perhaps a corruption of Cristóvão, i.e. Saint Christopher?) to a mountain range; possibly part of what we now know as the Drakensberg Mountains.

The map is too ‘pointed’: Algoa Bay is depicted north of False Bay (but they are on similar latitude). This error was partly responsible for shipwrecks… and this is where the map becomes particularly interesting. Three shipwrecks are described below.

Map historians will investigate the publication history of the map. I could track down only one other copy of the map: at the Scheepvaartmuseum [Maritime Museum] in Amsterdam. The Schrire’s map is listed in R.V. (Mick) Tooley’s seminal Collectors’ Guide to Maps of the African Continent and South Africa (page 117 and Table 45). This is not surprising because most of the maps listed in the book came from the Schrire Collection (click here for more details).

Tooley gave a publication date of 1753, as does the Scheepvaartmuseum. That is the date on which the VOC’s Secret Atlas was published by the van Keulen family. Indeed, I learned from Diederick Wildeman, the helpful curator at the museum, that the map is included in one of the copies of the Secret Atlas at the Museum; but not in its other copies. I determined from the website of the Dutch National Archives that the map is not in its copies of the Secret Atlas. So, I have concluded that the map came from a few ‘composite’ atlases (I do not know many copies were so bound) that contained other maps in addition to those in the usual secret atlas. So, this map in the Schrire Collection is both rare and scarce.

Epic Travels

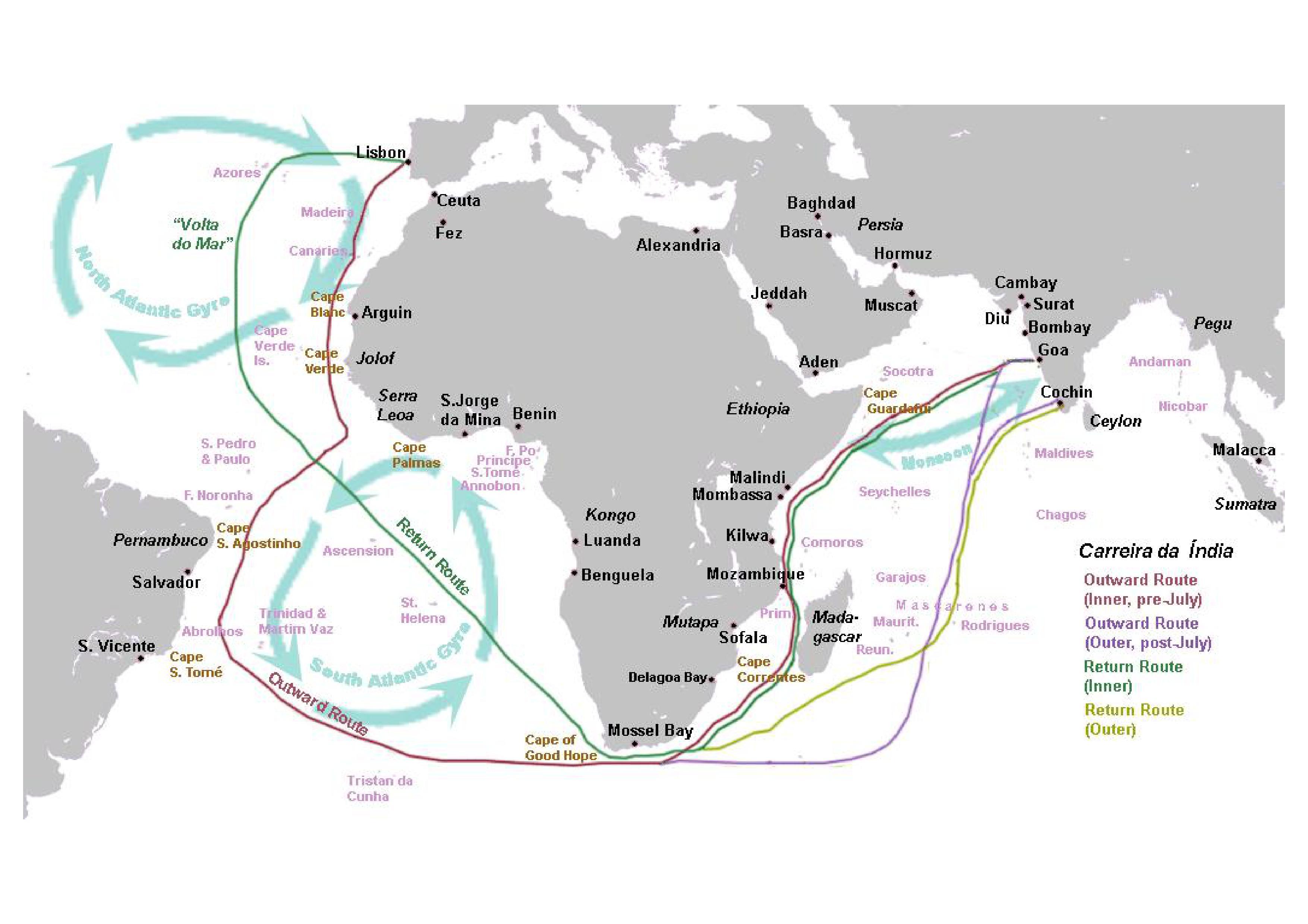

The Portuguese Carreira da India (India Run) of the sixteenth century followed a set route of travel between Portugal and the east coast of India. The route varied according to the seasonal monsoon winds.

In the sixteenth century Portuguese ships on the India Run followed these routes past the southern African coast (Wikipedia).

Some of the sea voyages must have been epic, but no specific voyages are depicted on the map. So where are the epic travels? They are off the map yet connected to it: Johannes van Keulen identified three shipwrecks, but the epic travels are of the castaways on land and one group also by sea.

Gail Vernon, formerly director of the East London Museum, and Carl, her ornithologist husband, read various accounts of the shipwrecks and stories of the survivors and followed their terrestrial routes in the field. Drawing on her Ph.D. dissertation, Gail described in some detail, and mapped, the castaways’ routes in her fascinating book, with a fascinating title: Even the cows were Amazed. Shipwreck survivors in South-east Africa 1552 1782. The title is drawn from the narrative of João Baptista Lavanha, one who described the castaways’ observation of the seemingly astonished reaction of the indigenous peoples’ cattle when they came across and sensed these odd-looking and odd-smelling castaways.

Shipwreck São João (1552)

Between 1497 and 1650, there were 1033 departures of ships from Lisbon for the Carreira da India (the ‘India Run’). The ostensible purpose of these voyages was to trade in spices but as evidenced from the description of the survivors, there was active slave trade even in the mid-1500s.

‘Hier verongelukt het galioen Ian’ [The galleon Jan wrecked here]; the fate of the São João was the first recorded shipwreck on the South African coast, a century before the Dutch settled at The Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese ‘galleon’, actually a very large carrack (AKA nau), was on its return voyage from Cochin (Kochi), which was the first European settlement in India.

The great galleon, the São João, ran aground on the 7th of July 1552, slightly east of the mouth of Rio do Infante according to the map. The Rio do Infante has been thought to have been the Kowie River or possibly the Great Fish River. However, some artefacts have been recovered (400 km north-east, at the Mthamvuna River, near today’s Port Edward and this is now considered to be where the São João ran aground.

Map showing where the São João ran aground

Recovered artefacts (Archaeology Digital Library)

Five hundred souls survived (including 300 slaves) the calamity. The castaways set off for the bay that Lourenço Marques had visited a few years earlier, Delagoa Bay. André Vaz, the pilot, and the captain led the party. They decided on a route close to the shore and one hundred and twenty survivors reached Delagoa Bay in December 1552. The party leaders did not develop good relationships with the indigenous inhabitants, although some individual castaways, with an unknown number of survivors remaining with the locals. Some castaways died in conflicts, and many died of hunger and diseases, including malaria.

Eventually, in January 1553, eight Portuguese and seventeen Asian slaves reached Inhambane, the Portuguese settlement (about 400 km north-east Delagoa Bay). They had travelled about 1000 km over a period of five and a half months. In Inhambane, they boarded a Portuguese trading vessel to return to India.

The story of the survivors was one of the great maritime disaster stories of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The author of the original account of their story is obscure, but it was the epic travels were included in Gomes de Brito’s História Trágico-Marítima. There is an informative memorial to the São João at Port Edward.

São João Memorial (SJ de Klerk)

Shipwreck Santo Alberto (1593)

The Portuguese carrack, Santo Alberto was on the return voyage from Cochin (Kochi) on the south-east coast of India. On 25 March 1593 ‘Hier verongelukt het galioen Albert’ [Here the galleon Santo Alberto ran aground]. Subsequent investigation revealed that she ran aground at today’s ‘Sunrise-on-Sea, near the mouth of the Kwelera River, about 20 km north-east of East London (left, a 1597 woodcut of the shipwreck).

1597 woodcut of the shipwreck

There were 285 survivors, 125 Portuguese and 160 slaves. They elected Nunho Velho Pereira, one of the heroes of the shipwreck, as their leader. It was a wise choice because it turned out that Pereira was an outstanding leader who also established good relationships with the indigenous population. Also, in contrast to the São João survivors, the Santo Alberto survivors took an inland route along established paths selected by local guides whom they had befriended.

They too set out for Delagoa Bay; on arrival they were ferried to nearby Inhaca Island: their journey had taken 88 days, they travelled more than 1000 km and 182 of the 285 survivors made it to Inhaca. They then waded across the nearby smaller island (now Portuguese Island), so named today after the burial of many Portuguese who initially survived the loss of São Thomé in 1589 near Dog Point, 25 km south of Kosi Bay. There were about fifty thatched huts and Portuguese trading vessels. There is no remaining evidence of the huts or graves. In July 1593 they departed for Mozambique Island where there was a well-established Portuguese settlement. Sixty-five Asian slaves and 91 Portuguese safely returned to India.

The informative account of the tragedy and epic journey was written by João Lavanha and the narrative is included in Gomes de Brito’s História Trágico-Marítima. Lavanha’s narrative is the earliest account of the indigenous people along the coastal plateau from the Kei River to the Lebombo Mountains – Gail Vernon considers it as one of the most significant accounts of pre-colonial southern Africa.

Shipwreck Stavenisse (1686)

On the 6th of February 1686 ‘Hier is verongelukt het schip Stavenisse of Stephens’ [The ship Stavenisse or Stephens ran aground here] … at R. das Forinigas, on the map.

Portion of the map

This Dutch flute was fully laden on its return voyage from Bengal to the Netherlands when it ran aground about 60 km southwest of Durban, to the north of the mouth of the Mzimkhulu River. There were sixty initial survivors who made it to land, one of whom was a French Huguenot teenager, Guillaume de Chalezac. He had joined the Stavenisse after an extraordinary adventure, which was recorded in English by Randolph Vigne in Guillaume Chenu de Chalezac, the 'French Boy' (Cape Town: the Van Riebeeck Society), 1993. The somewhat conflicting narratives of other survivors were captured by J.G. de Grevenbroek, secretary for the Council of Policy at the Cape of Good Hope. There are numerous castaway stories associated with the Stavenisse.

Group 1 - The forty-seven survivors of the shipwreck set out on a trek to Cape Town but were not successful. Despite numerous attempts, they were unable to make progress beyond Cove Rock, near today’s East London and remained in the area for almost two years; some castaways settled there permanently.

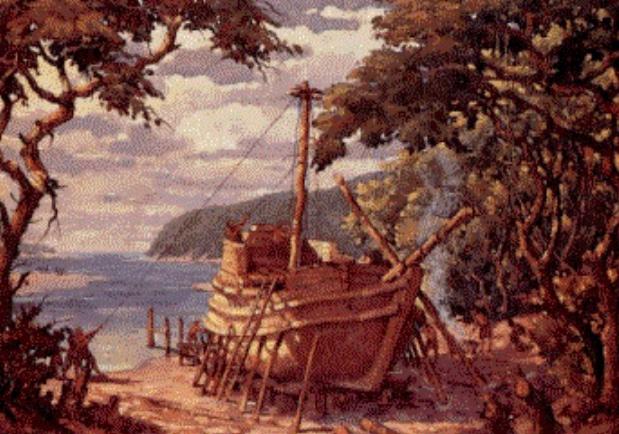

Group 2 - Soon after starting out for the Cape of Good Hope, thirteen of the survivors, including the captain, left the party and returned to the site of the shipwreck. Coincidentally, in May 1685, the British Good Hope ran aground off what we now know as Durban Bay; two Good Hope survivors visited the Stavenisse survivors once they heard that they were nearby. They invited the Stavenisse castaways to join them in Durban Bay in order jointly to construct a vessel from Good Hope material that they had retrieved from the wreck. This enlarged group was also joined by nine survivors from the Bonaventure, who trekked south from the wreck of the British ketch that had run aground in December 1686 at the St. Lucia estuary.

This enterprising group of diverse castaways constructed a seaworthy vessel from the wreck of the Good Hope, naming it the Centaurus - the name no doubt reflecting the hybrid vessel. On 17 February 1687 all but five of the party boarded their ship and set sail for Cape Town, which they reached without mishap twelve days later. Simon van der Stel, Commander of the Cape, was so impressed with the ship and stories of ivory to the north-east that he bought the Centaurus.

Centaurus (Van Riebeeck Society)

After some repairs and additions, the Centaurus set sail in November 1687 and rescued the survivors of the Stavenisse at Cove Rock. Two other Stavenisse survivors, still at Durban Bay, were rescued by another small ship, the Noord, which collected yet another castaway still at Cove Rock. In all, nineteen from the Stavenisse shipwreck made it back to Cape Town, including Guillaume de Chalezac, the ‘French boy’.

Conclusion

So, an investigation into the publication history of a scarce map has transformed into a laconic story of the epic travels on land and even on sea of castaways of three shipwrecks on the southern African coast.

A notable feature of the stories is that both São Joã and Santo Alberto carried numerous slaves from India who were destined for Europe, some African and some Asian. It is well known that the Portuguese took slaves from Mozambique to their factories in India, but relatively little seems to be known about the Asian slaves sent to Lisbon. Gail Vernon devoted s chapter to the subject of slaves on the shipwrecks; it seems most were servants of the Portuguese returning from India. Surviving African slaves integrated into the local communities, while the Asians returned to India.

‘That's the thing about maps. They let you travel without moving your feet.’ With apologies to Jhumpe Lahiri (The Namesake, New York, 2003)

Main image: ‘Paskaart van het Zuydelykste Gedeelte van Africa … Met alle Desselfs Voornaamste havens ende dieptens Door Johannes Van Keulen te Amsterdam’ / Map of the Southernmost Part of Africa … with all its principal harbours and depths. By Johannes Van Keulen in Amsterdam. (The map at the Scheepvaartmueusm may be viewed in high resolution here)

Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.