Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

John Lincoln's series on the history of Cullinan continues. This article looks at the village and surrounding area during World War II. Click here to view the series index.

In 1932 the mine closed for a second time and the village became a virtual ghost town. That was until 1939, when the military arrived. It was probably the vacant houses and the abundance of open veldt in which to practice manoeuvres that led the military to decide to select the Village and surrounding area to construct a massive camp.

The village was also connected to the railway network. The decision to construct the Italian POW camp at nearby Sonderwater (now Zonderwater) was probably influenced by its location well inland, as well as the close proximity of the SA Armed Forces.

The regiments of the forces decided to construct emblems of their military regiments on a koppie in the village. The two bagges visible in the above photograph are the “Regiment de la Rey” and the “Witwatersrand Rifles”. Other badges are “The Second Royal Durban Light Infantry”, the “Pretoria Regiment (Princess Alice’s Own)” and the “Central Army Training Depot” (John Lincoln)

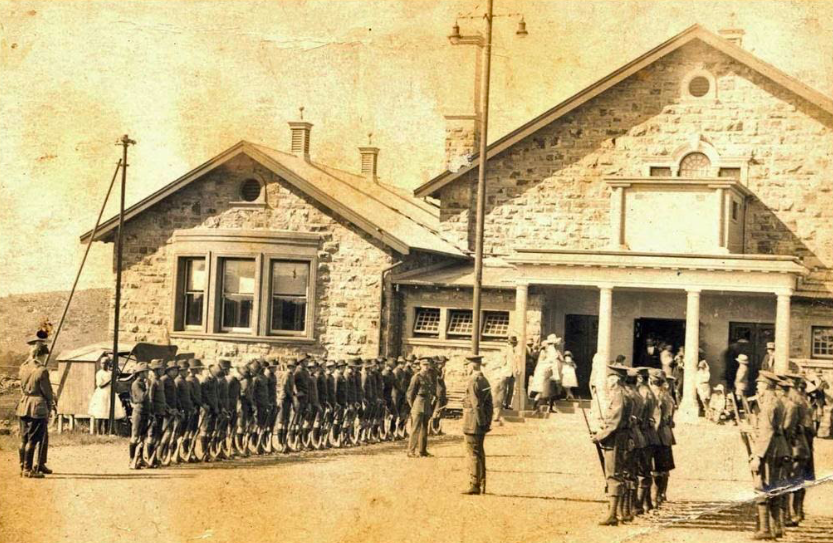

Men of the South African Army arrive at the Cullinan railway station (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Besides occupying all the empty houses in the village, the Army built massive army camps close to the village, even on the local golf course. They took over the local hospital as well as the hotel, where the bar was out of bounds except to officers. At the hospital a memorial plaque was dedicated to the SA Medical Corps in 1940. Many additional buildings were constructed around the hospital.

Memorial to the South African Medical Corps (John Lincoln)

Monument to the Dental section of the South African Medical Corps (John Lincoln)

The hospital itself was constructed in 1908, the corner-stone being laid by Lady Cullinan. The hospital is still in use today. The instruments and operating theatre used by the Army doctors are believed to be those on display in the history room at Cullinan Tourism and History.

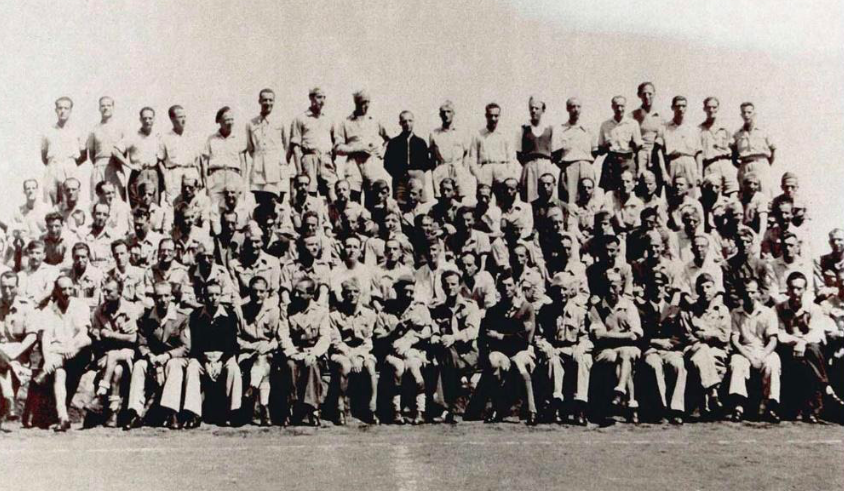

The South African Medical Corps outside the mine hospital (Cullinan Mine Archives)

At nearby Zonderwater, another memorial plaque to the Dental Corps of the SA Medical Corps was unveiled, which still exists.

The Army in Cullinan

A section of Oak Avenue, the main street down to the mine, was cordoned off with fencing and guard huts, housing the women of the SA Army. Many of the off-duty women used to meet in the McHardy household. The original manager of the mine who came here in 1903 was a William McHardy. Two of his daughters were still living in the house and off-duty women would meet there to play billiards and cards. The house is now a museum.

The local Recreation Club was handed over to the YMCA for the duration of the war to entertain the troops. A letter submitted to the Premier Mine’s in-house magazine by Lucy Nichol in 1975 might better explain the connection between the Military and the Village:

Three years ago while travelling on one of those mini-buses striped like a zebra, through the dust of the Wankie Game Reserve, a gentleman sitting opposite enquired where I was from. ‘Cullinan, where Premier Mine is,’ I replied. ‘Oh, ’he explained with a smile and a look of fond recollection. ‘Were you one of the ladies who fastened the teaspoons to the ceiling with string? Fellow travellers looked rather startled at this. 'Yes, all three of them,’ I said. ‘Do you know by any chance what happened to the other 497?’ And so our memories returned to the war years in Cullinan, when the Recreation Hall was handed over to the YMCA ‘for the duration’ for the entertainment of the troops, and the canteen was opened where the local ladies served every night.

The Recreation club during the war years (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Mr. van Buuren came from Johannesburg to organize and cheeky ‘Mickey’ Rooney was in charge locally, helped by Messrs. H Bennet and OG Philip who handled the projector where needed.

Miss Elie Robson and Mrs Jean Lynott donned khaki and ran the canteen during the day and Mrs Lynott continued alone after Miss Robson left. Miss E McHardy was appointed Commandant and Miss E Cheffins, Adjutant. Mrs D Philip organized the local ladies into shifts to run the canteen in the evenings, beginning at 5pm and continuing to the end of the entertainment or the last soldier had reluctantly departed. We generally worked 2 shifts each weekly, but often the cry for help was sent out, ‘a new draft is in, we are crowded out, collect as many as you can and come at once or sooner.'

A long counter stretched across the far end of the canteen laden with cups and saucers, the urns of coffee bubbled behind, flanked by heavy teapots, and tea and coffee was sold at one penny per cup. We all took a turn in the kitchen at the bread cutting machine, slicing through crates of tomatoes, mashing dozens of eggs, grating pounds of cheese and passing the continuous relay of dishes of sandwiches through the large hatch.

At times our customers stood 5 and 6 deep, but when a show started, half would stampede away for a while to surge back at the interval.

In the corner, bottles of cold drink were on sale, everything but soda water. ‘Why?’ I enquired once. ‘Because the YMCA is a temperance association,’ I was told severely. Dear innocent far-off days, when only a soda was a temptation for mingling with strong liquor.

A long counter dominated by a large and noisy till ran between the two hall entrances and it was stacked with an extensive variety of cigarettes and confectionery, and all those items a man away from home needs, such as writing and mending materials, hankies, penknives and toiletries.

Well, shall we get to those spoons? We opened with 300 new thick white teacups and saucers, spoons and plates, but as the months passed their number became depleted and another 200 were issued and if possible they disappeared even quicker. ‘A man needs a tooth mug’ said one, putting his into his pocket, and of course many were lost in the crash and bang of the frequent washings up. When these faded out, we were issued with glass cups and saucers ‘with knobs’ the only kind obtainable now with prices astronomical, and we were instructed to look after them.

Of course, they dwindled too and finally we unpacked cases of shining silver mugs, no condensed milk tins, carefully finished off, with inch wide handles soldered on. The point of no return seemed to have been reached when a would be customer had to first hand in a used mug which we plunged into buckets of hot water under the counter.

The evening came when I entered to see 3 spoons hanging on strings from the ceiling at intervals, each lying neatly on a plate next to a huge bowl of sugar, and even then a customer was seen trying to use a surreptitious pen knife.

So that is how Cullinan became famous for ‘spoons on strings.’

Bioscope shows were generally given twice weekly, concerts of varying talent, and every play produced in Johannesburg came over for at least one night’s free performance. An out-standing occasion was when Noel Coward, who was touring all the camps, came out and provided a full evening’s entertainment.

'For those in uniform only.’ We were warned beforehand and stories were whispered round of a certain place where he had refused to begin until every civilian had withdrawn.

We were very thrilled when extra chairs were erected in the aisles, defying fire regulations and all canteen workers resplendent in white starched overalls and YMCA badges together with members of the nursing staff were gathered in.

Noel Coward really gave one of his best and held the audience from start to finish. ‘Don’t put your daughter on the stage Mrs Worthington’ and the nostalgic, ‘I could have danced all night, ’excerpts of dialogue from his plays, little jokes and big laughs, and song after song. Never before, or since, can the hall have echoed to such tumultuous cheering and applause.

An endearing memory has recently returned to me while thinking of those times. For some reason, possibly bad acoustics, the film shows were given one summer on the natural terrace on the side between the Hall and the main road, and it was most relaxing to sit on a mild evening under a starlit sky with the dark shadowed trees around. Gradually the little golf caddies and their pals would creep up, and sit in rows on the ground at the very front, their reactions very often more fascinating to watch than the film. Local families gathered round complete with prams, the natives shyly stood near, and cars passing along the main road stopped.

There was such a feeling of ‘togetherness’. Our greatest and most important occasion was the visit of Ouma Smuts to thank all who were working for ‘my boys.’ She was accompanied by her daughter, Mrs Weyers and a senior YWCA lady official I think, and in a photograph you will see most of us gathered to welcome her.

Ouma Smuts outside the Rec. Club with ladies of the YMCA (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Perhaps our war years in Cullinan sound too light hearted and carefree but I know there was not one worker in white without some of her family involved in the fighting and there were many anxious times and shared sorrows and personal tragedies before it was over.

Officers swimming pool at Zonderwater Prison (John Lincoln)

Guard hut inside the grounds of Zonderwater Prison (John Lincoln)

Around and at nearby Zonderwater are many buildings going back to when the Army was here during the war. Some are in the prison block, and others are looked after by residents of a house in Zonderwater Road. (John Lincoln)

Unknown group at Sonderwater (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Possible concert at Sonderwater (Cullinan Mine Archives)

The Army marches past the hotel (Cullinan Mine Archives)

The Italian POWs at Sonderwater

During the Second World War, the South African Armed Forces accepted the surrender of the main Italian force in Abyssinia. These POWs were transported to South Africa, to Sonderwater to be exact. It made sense to open a POW camp close by one of your main Army camps. At first there were few facilities to house these POWs, but gradually life was made a little easier for these prisoners when the tents they had been housed in were replaced by permanent barracks. Roads, churches and soccer fields were constructed.

Camp schools were started to teach those Italians who had never had the luxury of a formal education, to read and write and over 200 POWs were employed as teachers in these schools.

A training centre was built to train the prisoners in the basics of mechanics and carpentry.

Many of the POWs were allowed to work on the nearby farms and were often allowed to wander freely through the streets of Cullinan. In fact, the shops of the Co-operative Society in the village even stocked pasta to sell to them.

There were up to 63 000 prisoners in the camp, 263 of whom died there and are buried in the graveyard at Sonderwater.

Italian POW named Mario (Gouws Family)

Italian POW (Gouws Family)

Sweetheart of Italian POW (Gouws Family)

Mr and Mrs Orselli at Zonderwater (Gouws Family)

Cemetery at Sonderwater, now Zonderwater

There were 20 theatres in the camp and as many as 1000 POWs were employed as actors, producers, stage hands etc. The productions varied from the very serious to light-hearted comedies. The costumes for these productions were made by the prisoners themselves.

Concert performer, Italian POW (Gouws Family)

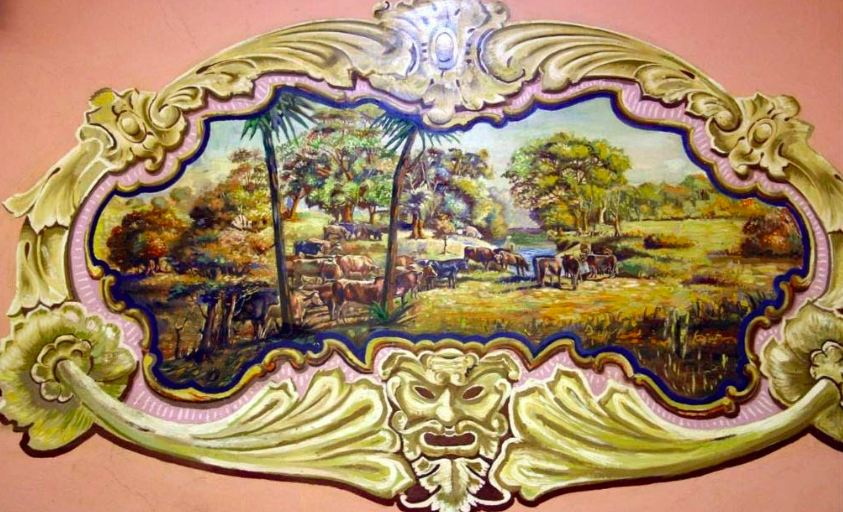

An art centre was established in the camp, and some of these gifted Italians painted massive four metre by three metre murals, depicting British and South African scenes, onto the walls of the Premier Mine Recreation Club. The names of the artists are unknown. The paintings, of great historical value, were unfortunately covered over with soft boarding in 1948 to improve the acoustics in the hall for the newly installed cinema projectors, and it was only in 1993 that these works of art were rediscovered. All of them were damaged, some severely, due to the boarding being nailed to the wall. There are eight paintings in all: three are copies of South African paintings, one each of Westminster, the Union Buildings, Tower Bridge in London, a sailing ship and finally a bush water scene.

All the paintings have been restored to their previous splendour and since the discovery have been seen by thousands of visitors from all over the country and outside the borders.

Murals painted onto the walls of the Premier Mine Recreation Club circa 1942. They were covered over in 1948 to improve acoustics for newly installed cinema projectors. (John Lincoln)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.