Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Philaphotographologist – what a highfalutin word! The word does not actually exist. Rackham (2022) applied his creativity and constructed the word following some discussion on the internet.

Personally, I rather like the word. It did take me a minute or two to get my tongue around the pronunciation though (feela-foto-grafologist).

Rackham (2022) constructed the word as follows: Phila (to love), derived from French, followed by the two Greek words phōtós (light) and graphê (drawing) and concluding with the Latin word logia (branch of knowledge).

The word philaphotographologist translates into more understandable language, namely photograph enthusiast or photograph collector. That is what this article is about, an early South African photo enthusiast.

As a psychologist, I am intrigued by the visual orientation, or the lack thereof, in the human race.

Some of us are more inclined to a heightened visual curiosity compared to others. Those of us who have a lower level of aesthetic visual appreciation will be less inclined to give much attention to visual imagery, in this instance photographs, whilst to the visually curious, photographs provide visual stimulation.

In my mind, a person has to be visually curious to be referred to as a photo enthusiast, or a philaphotographologist for that matter.

One such person was Frederick William Willis. British-born, he became a South African citizen, initially attached to the South African Constabulary.

He loved photographs – so much so that he passionately constructed photo albums containing various themes.

I was privileged enough to get my hands on two of these albums constructed by Willis. These were offered to me by a Pretoria-based antique dealer who is aware of my enthusiastic research on South African photographic history.

Something never seen by me before is an album filled with more than 500 South African-themed picture postcards whilst the second holds a combination of some 150 personal photographs inclusive of crime-scene imagery. The latter album consists of a combination of amateur photographs as well as professional photographs which would have been purchased directly from professional photographers or over the counter back then.

1. Frederick William Willis (1880 – 1966)

Little is known about Willis. Family, who must have inherited the albums, could not be traced.

The brief reconstruction of Willis’s life narrative was obtained directly from the albums, the South African National Archives or from internet sites.

Willis was born on 13 March 1880 in Maidenhead, Berkshire. He had one brother, Alfred John Willis.

As a young man, whilst still based in the UK, he derived income as a wine merchant’s barman as well as a calling porter.

His relocation to South Africa followed when in July 1902, aged 22, he applied for a role with the South African Constabulary (SAC) recruitment team based at Kings Court in Westminster. Although he could not shoot or swim at the time of his application, he was appointed to the SAC on 16 October 1902. Before his official joining, he first had to obtain some target practice, duly signed off by an officer.

On his appointment, he was granted a free passage to British South Africa and on arrival completed a 6-week training program whereafter he was appointed as a depot trooper in March 1903.

Willis only served in the SAC for 175 days. He resigned to join the Transvaal Town Police (TTP) on 7 April 1903.

The SAC was a paramilitary force set up in 1900 under British Army control to police areas captured from the two independent Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State during the Second Anglo-Boer War.

After the hostilities ended in 1902, the two republics became British colonies. The SAC was disbanded on 2 June 1908 with the Transvaal Police and Orange River Colony Police replacing the SAC in those respective locations. Many SAC constables joined one of these two forces and continued to serve the new Union of South Africa in the state-wide, centralised South African Police (SAP), which was formed in 1913.

Willis was one of several SAC constables that made South Africa his permanent home.

Towards the end of 1905, Willis took three months leave to return home (Acton, London). It is assumed that this was the first time he had returned home after arriving in South Africa in late 1902. Could he have gone home to get married?

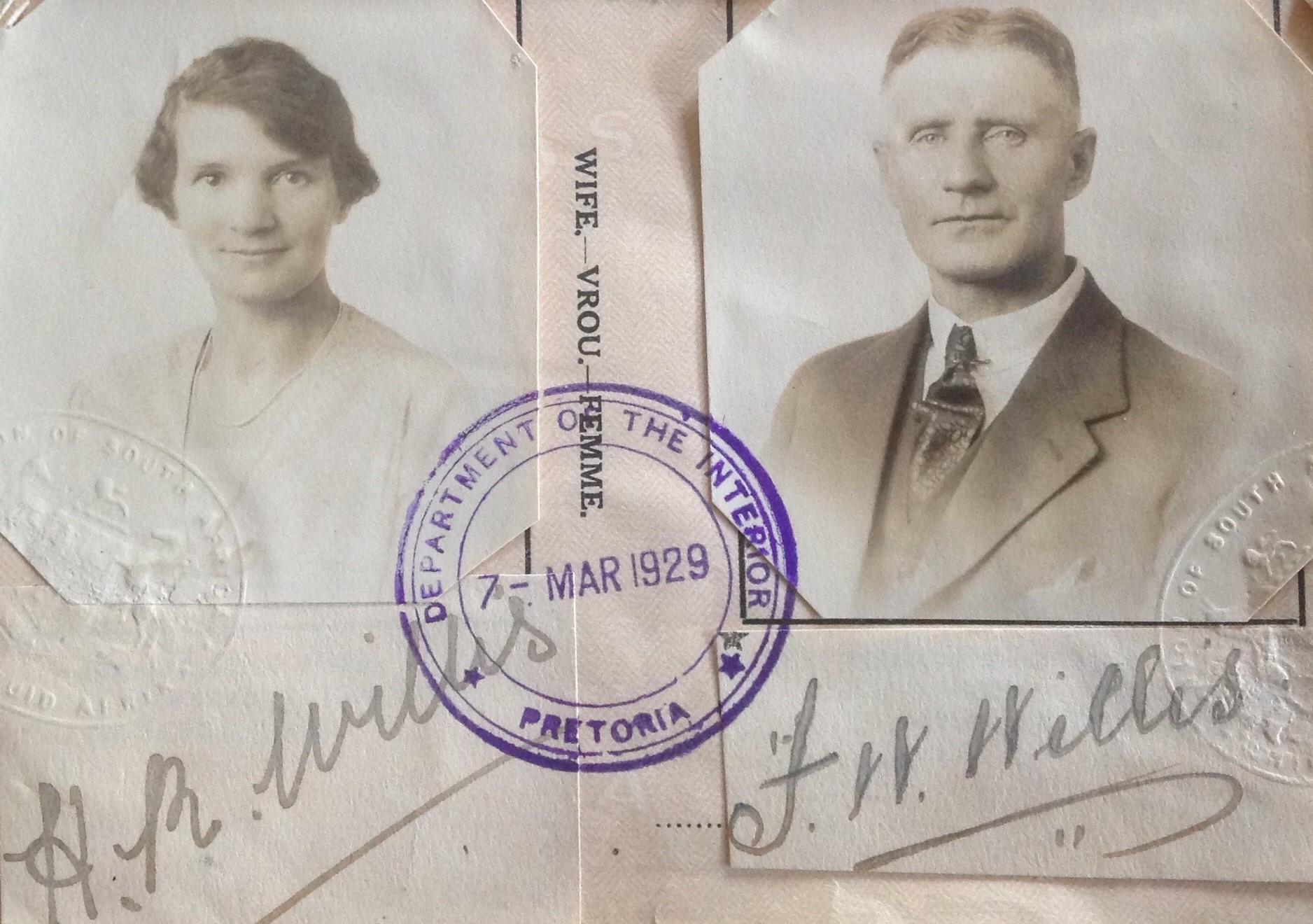

He was married to H.R. Willis. At the time of publishing this article, I have not been able to determine her full name or her maiden name. It is also not known when or where the couple got married. Family photographs found in the back of the album suggest that they had two children - a boy and a girl. The two albums referred to in this article in all probability originated from the offsprings of these two children.

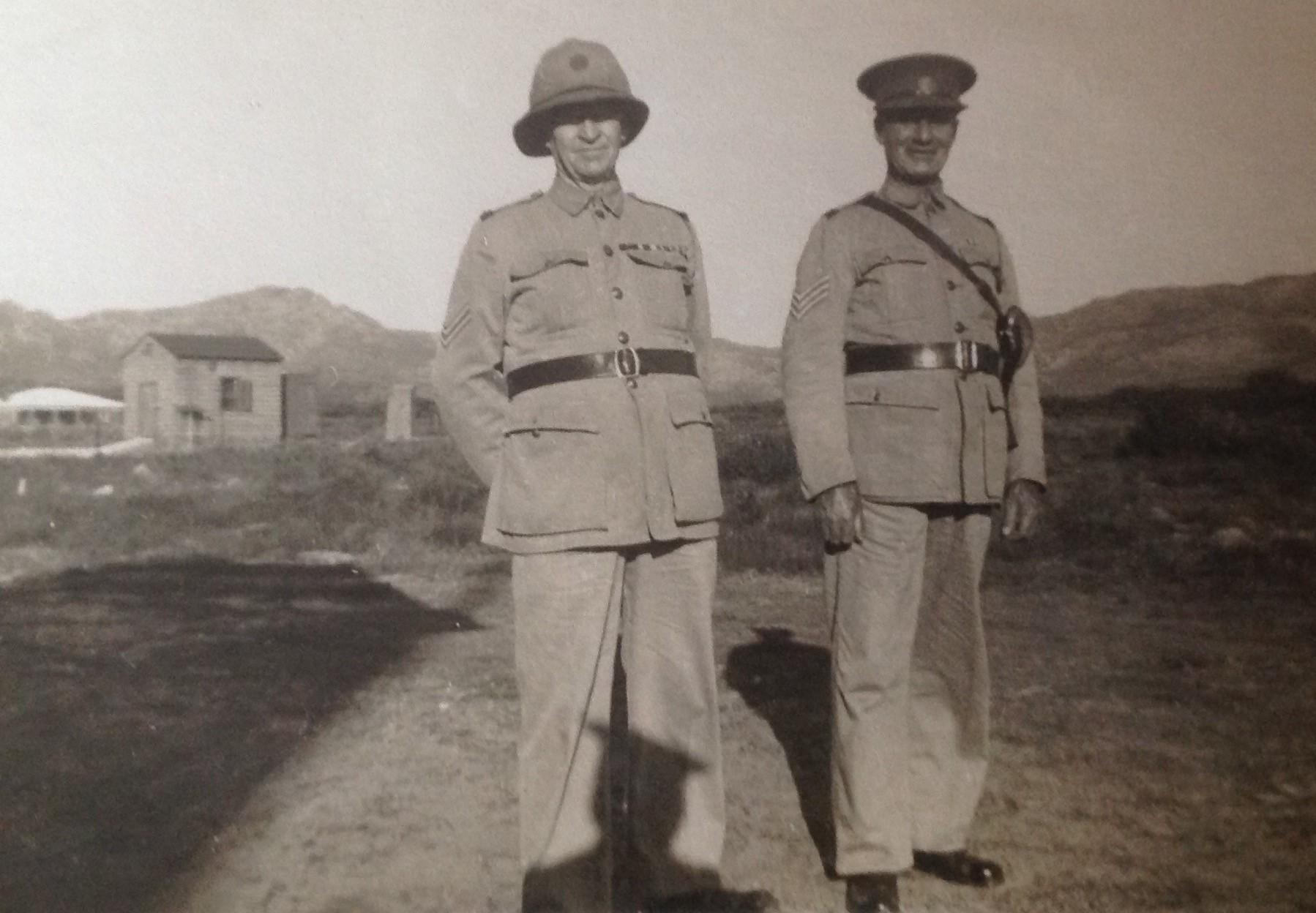

Willis’s personal photographs indicate that he progressed from Constable to Detective and then Detective Sergeant. From this it is assumed that he retired from the South African Police service in the early 1940s.

Passport photographs of FW Willis and his wife taken in Pretoria during 1926

Sergeant Willis on the right (circa 1940s)

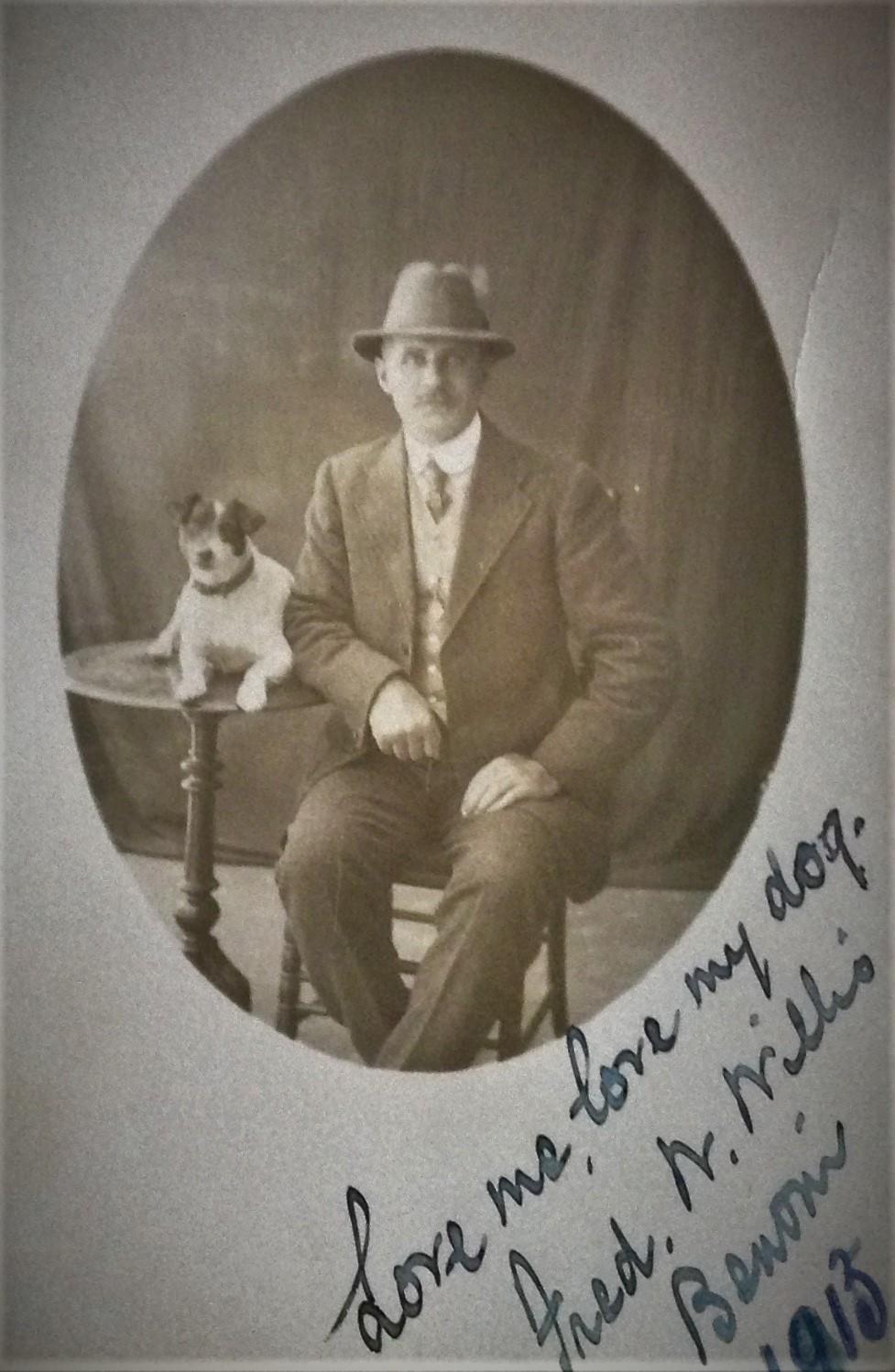

Love me, love my dog. Picture Postcard photograph captured in Benoni in 1913.

A Willis family outing. Willis stands with his two children at the back with his wife in the foreground (circa 1930)

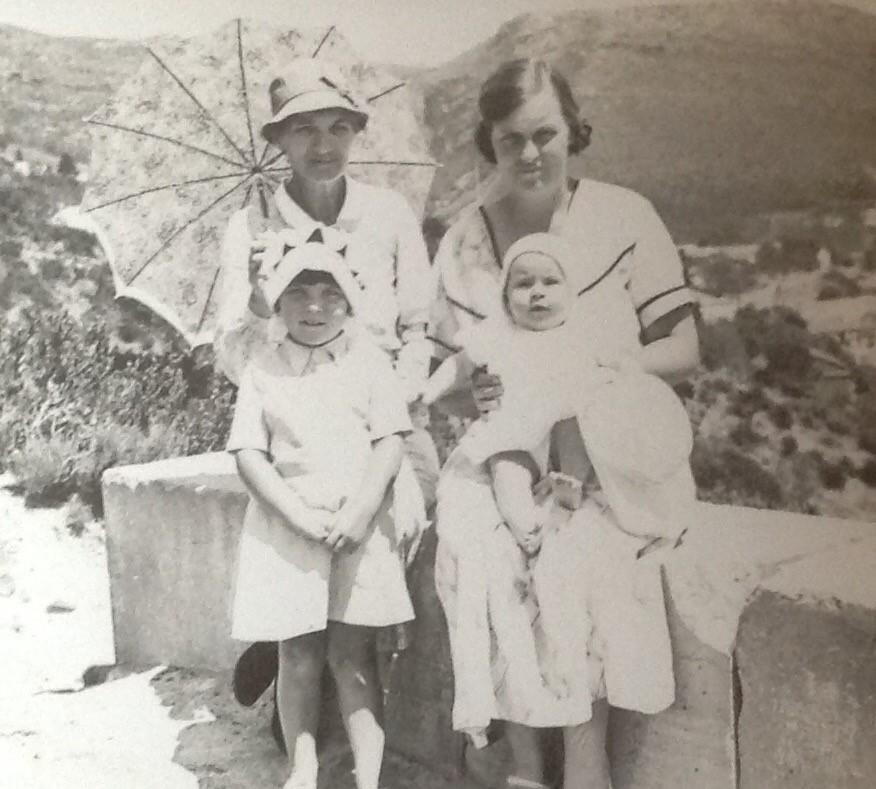

The Willis family of four clearly loved travelling. Somewhere in the mountains (circa 1930s).

Granny Willis with her daughter and two grandchildren (circa late 1940 early 1950)

2. Album analysis

On the front page of both these albums, Willis has applied a rubber stamp containing his name followed by the acronym PCC (which probably stands for Pretoria Constabulary Constable) and Transvaal Police – Pretoria.

The first of the two albums is described below as the “Photo Album” whilst the second album is described as the “Postcard Album”.

2.1 Photo album

The photographs contained in the albums date back to the early 1900s, with the large majority dating from pre-1915.

The back of the photo album contained several unmounted black-and-white family photographs dating between the 1910s and 1930s. None of these photographs had information captured on them, other than two passport photographs of Frederick and his wife dated 1929. These two images alone assisted in reconstructing some sort of narrative around the Willis family, albeit incomplete.

There clearly was strong camaraderie amongst the men in uniform in that the album contains photographs of a few of his colleagues as well. The camaraderie was so strong that Willis included photographs of the gravestones of two of his colleagues (Constables Jones & Tully) who died in action.

Although Willis seems to have been Benoni-based for most of his career, he was so taken by Pretoria that the album contains several photographs taken on Church Square during military parades. At some of these events, his colleagues were on duty. Handwritten notes in the album point them out on the photographs (see photographs at the end of this article).

In the album, Willis included some crime scene images. These photographs are clearly amateur photographsAn amateur photographer took these, many of them presumably by Willis. These images in themselves, create a perspective of early South African crime scenes.

Although it would have been difficult to regulate at the time, I cannot imagine that it was allowed for detectives in the police force to have crime-scene-related images in their possession.

My personal favourite photograph contained in the album is that of Willis and five of his Benoni Flying Squad colleagues standing next to their motorcycles.

Amateur photograph of fatal vehicle accident. The driver, one Gross, drove his vehicle into the ditch in Benoni in 1914.

Amateur photograph of Willis and colleagues captured in 1914. Standing at the back from left to right: Constable Viljoen, Constable Morgan, Detective Joyce and Detective McLean. In front, from left to right: Detective Willis, Detective Baker and Detective Murphy

Amateur photograph of the Benoni Flying Squad in 1916. The detectives standing at their motorcycles are from left to right: Murphy, Burns, Willis, O’Connor, Grosvenor & Rae. The registration plates on the bikes are TA (Benoni), TB (Boksburg) and TJ (Johannesburg)

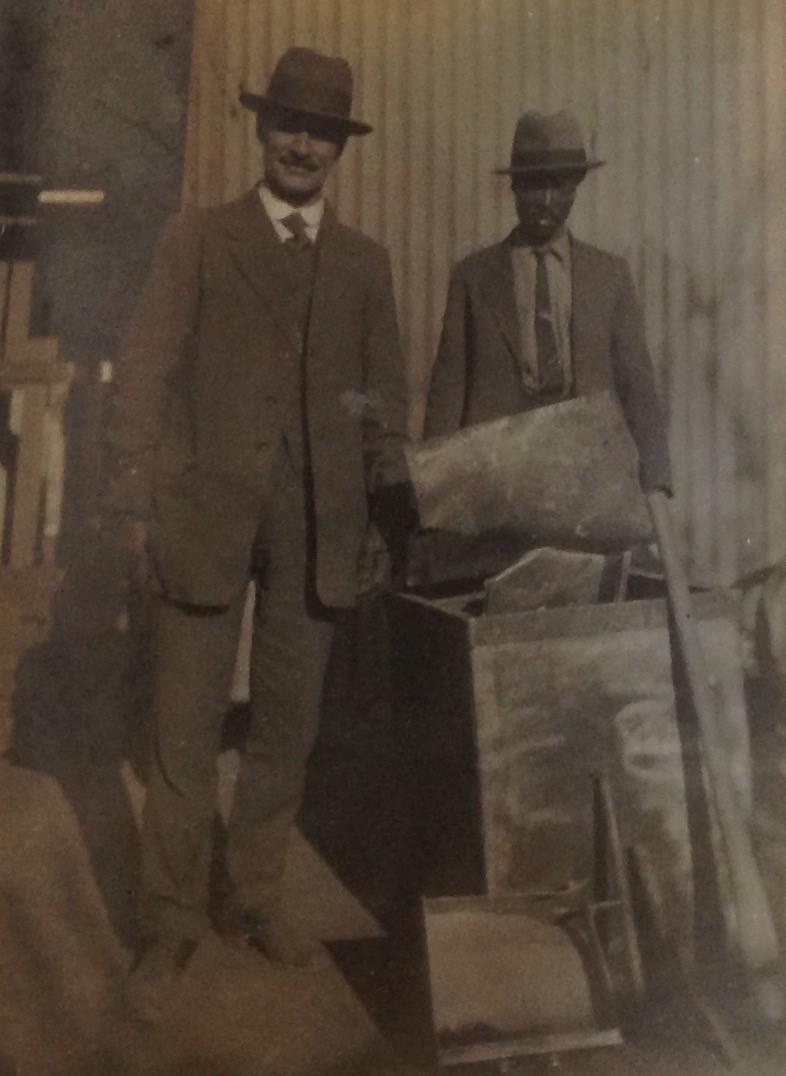

Amateur photograph of Detective Sergeant Willis with Detective Jim in 1918 standing at a safe that was forcibly opened by criminals in Benoni.

Amateur photograph of Leliebloem House in Woodstock in the Cape where a murder was committed in 1918. According to the inscription in the album, the house was built in 1768.

During the 1913 miners’ strike in Johannesburg, Willis was clearly on duty in that the album contains some photographs of the consequences of the strike. These photographs he would have bought from the professional photographer O’Byrne at the time.

The strike came about when workers at New Kleinfontein mine embarked on action in June 1913 to persuade management to recognise their union rights, an eight-hour day, and the reinstatement of workers who had previously been dismissed.

Mine owners attempted to sidestep the unions and kept the mines in production by using scab labour. Strikers urged the scab workers to join the strike, but police forced Black miners to work or remain in the compounds.

By the end of June, about 18,000 miners, attached to 63 mines, were out on strike throughout the Witwatersrand. Strikers were instructed to come armed to resist any unlawful force which may be used against them.

With no army in existence, Smuts called in the police, mounted riflemen, and the remaining troops of the British garrison and deployed them to the Rand.

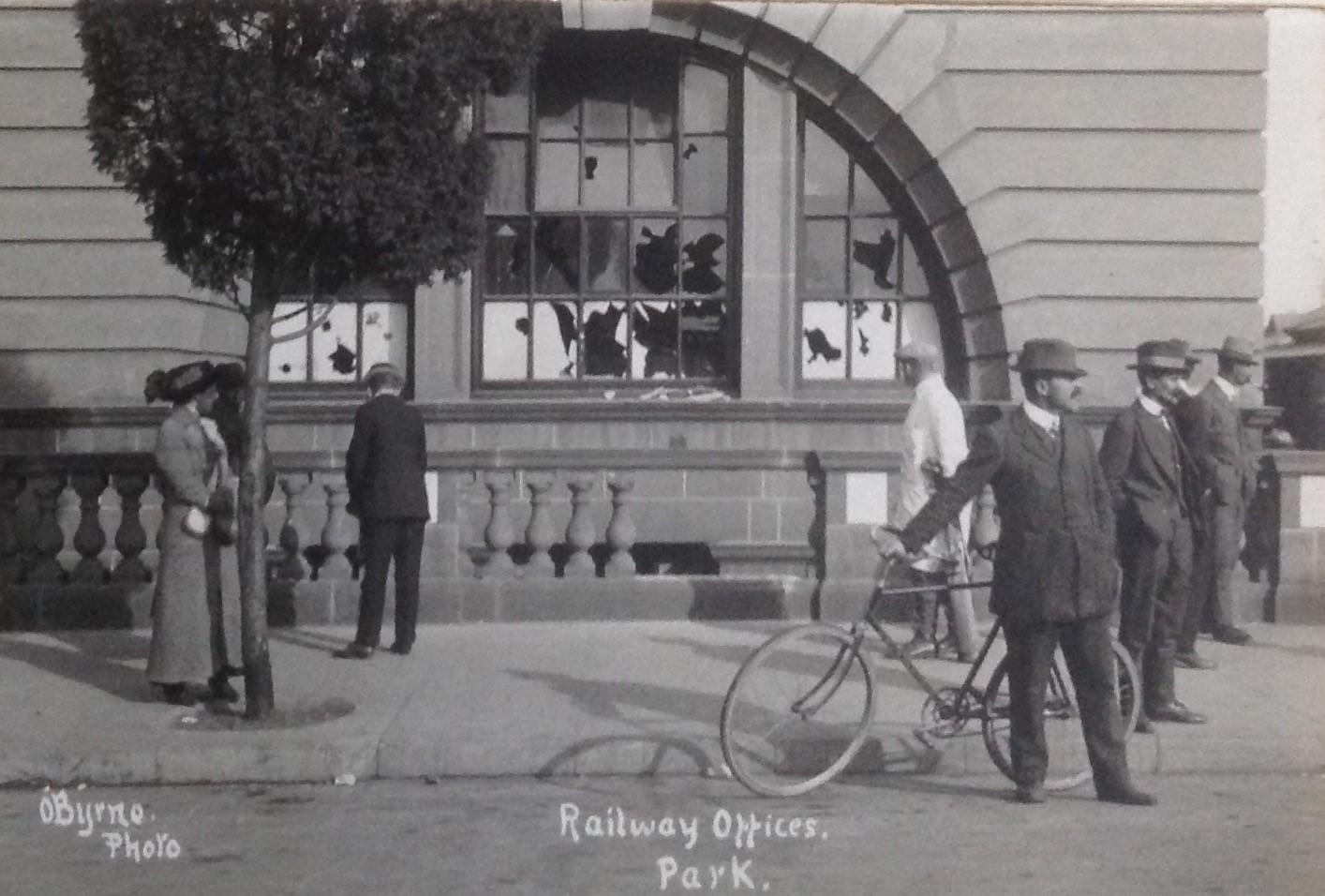

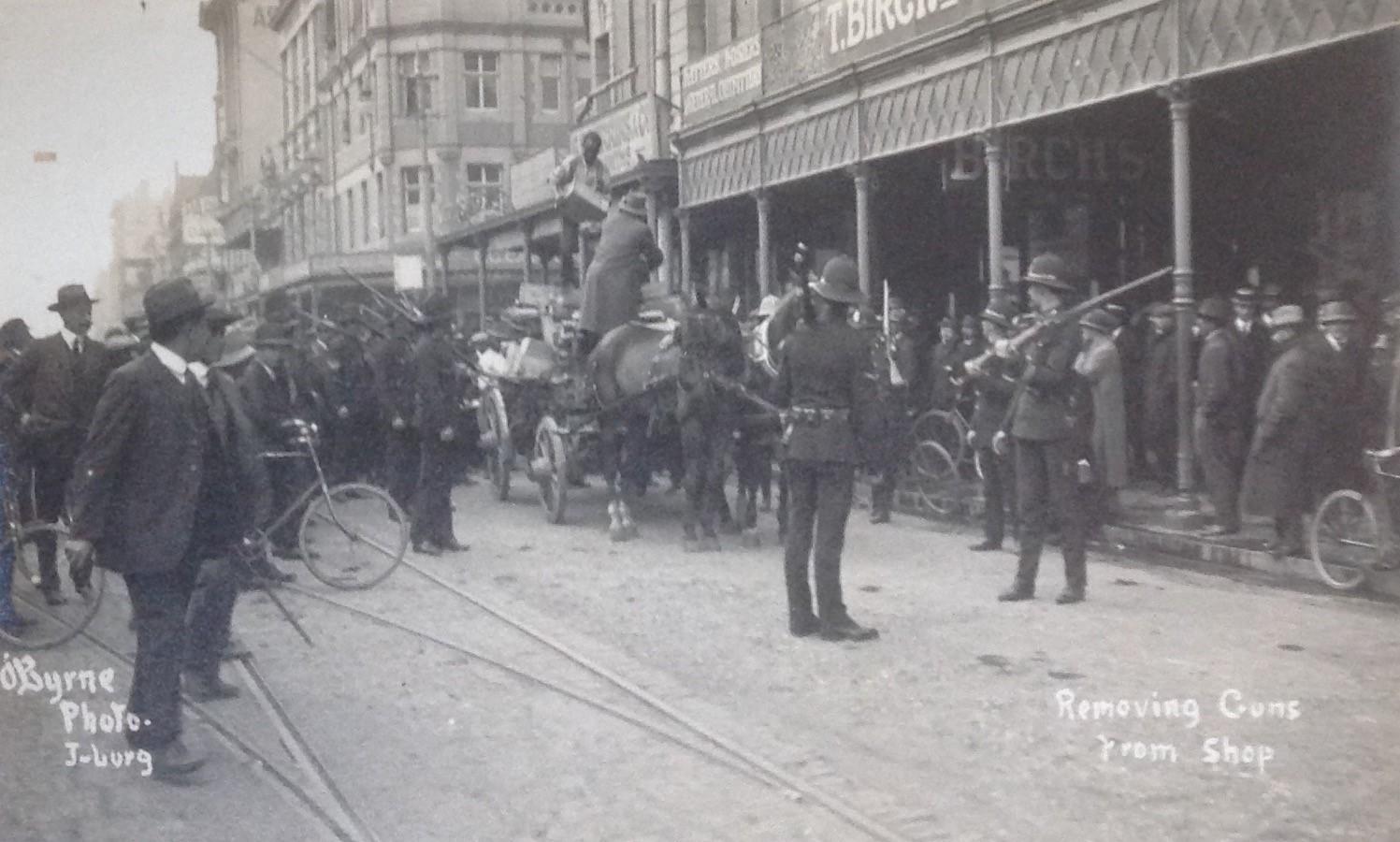

Mayhem ensued as crowds rioted, stopping trams, forcing staff off the trains, and engaging in destructive behaviour. A wooden ticket office at the main railway station was burnt, the bar was raided, and the premises of The Star newspaper were set on fire as the newspaper was seen as the mouthpiece of the mining magnates.

Clashes also took place outside the Rand Club, the favourite venue of mine owners. Demonstrators tried to enter the club, but they were fired upon by the armed Dragoons.

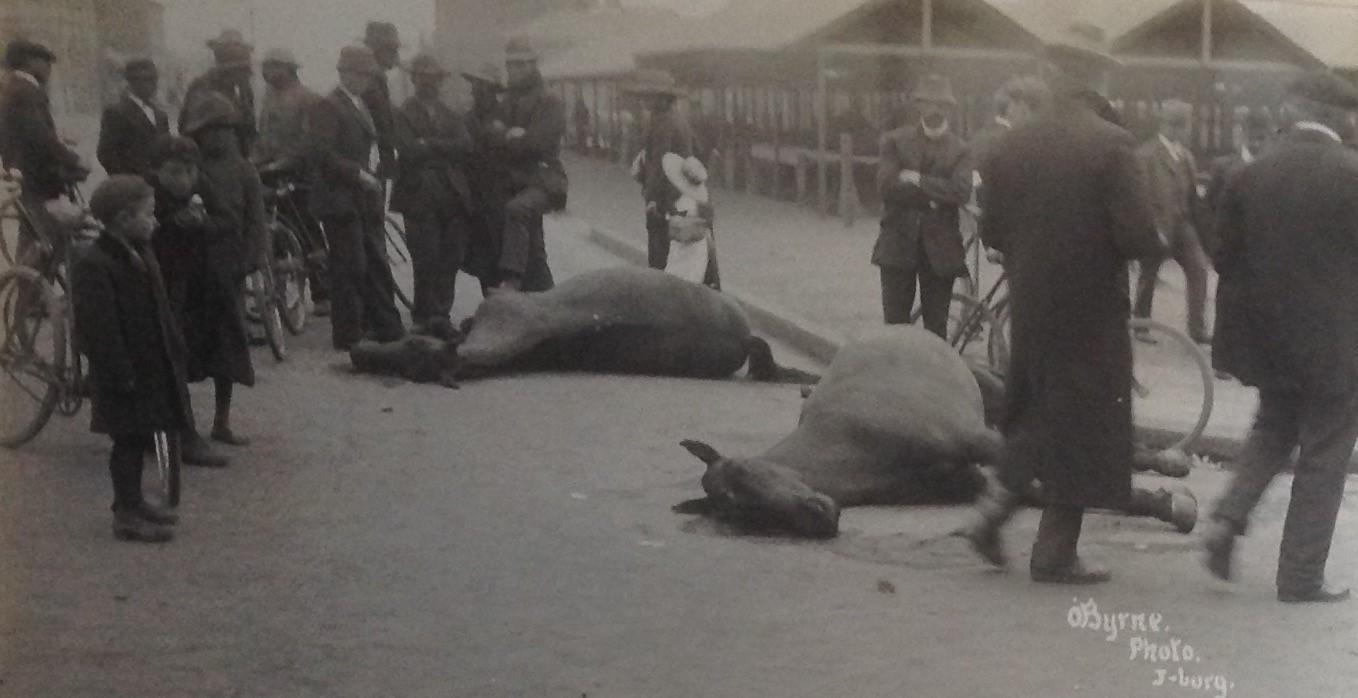

More than 20 people lost their lives during the riots.

Alarmed by the reports of violence and death, Botha and Smuts rushed to Johannesburg from Pretoria to negotiate with the strikers. The demands of the strikers were acceded to.

The strike events clearly had Willis intrigued, so much so that he had to include images of the event in his photographic “storybook.”

Damage caused to Johannesburg railway offices during the 1913 miner strikes. The male in the foreground with the bicycle is Detective Parker. Photograph by professional photographer O’Byrne.

A wooden ticket office at Park Station burnt to the ground following the 1913 miner strike. Photograph by professional photographer O’Byrne.

Firearms being removed from Walshe’s shop under police guard during the 1913 miner strike in Johannesburg. Photograph by professional photographer O’Byrne.

Curious onlookers at the Fountain Bar in Johannesburg observing bullet holes in the windows of the bar following the 1913 miner strike. Photograph by professional photographer O’Byrne.

Curious onlookers standing at horses shot by miners during the 1913 strike in Johannesburg. Photograph by professional photographer O’Byrne.

2.2 Postcard album

When antique postcard albums are uncovered in South Africa, they usually contain only a few South African cards amongst the multitude of foreign, often dull and boring, cards.

The Willis-constructed album is however significantly different in that it contains only South African cards – more than 500 of them. What an unusual find! The visual content of the album relates to significant cultural, social, and historical events in South Africa.

This album confirms that Willis had a keen interest in his newly adopted country – South Africa. The content of the album touches on a broad spectrum of themes such as ethno-photographic imagery, the Anglo-Boer War, Pretoria, South African railway stations, Chinese labourers in Johannesburg, mining, and many more. As an avid deltiologist myself, even I have not seen many of these cards before.

The visual evidence, as presented on these cards, is undeniably imagery that was produced while events and changes in South African society were unfolding during the turn of the 19th century. Today, these miniature historical records of life at the time, provide us with a rich reflection and insight into our own ethnic/cultural history.

It is worthwhile briefly reflecting on some of the themes contained in the card collection:

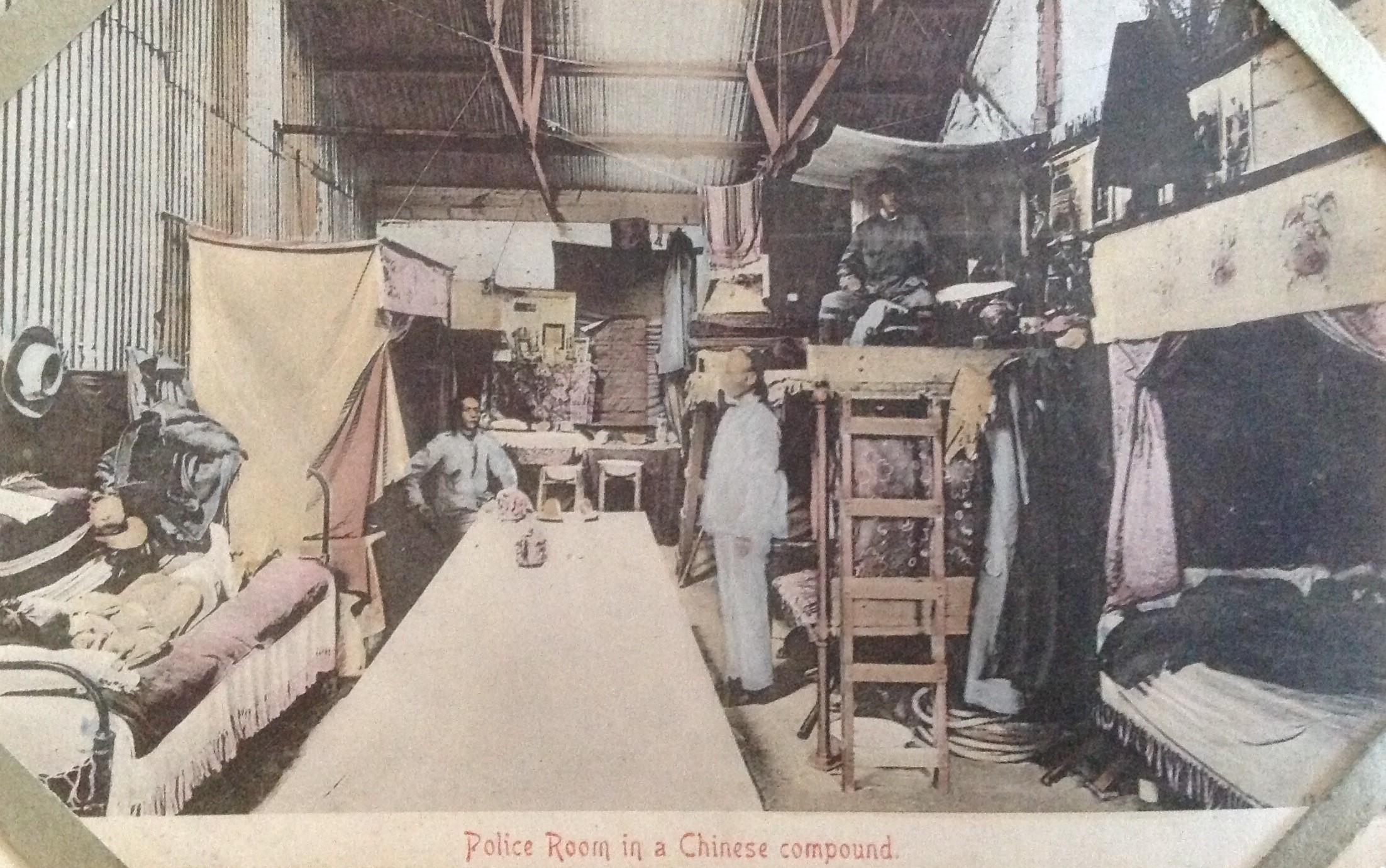

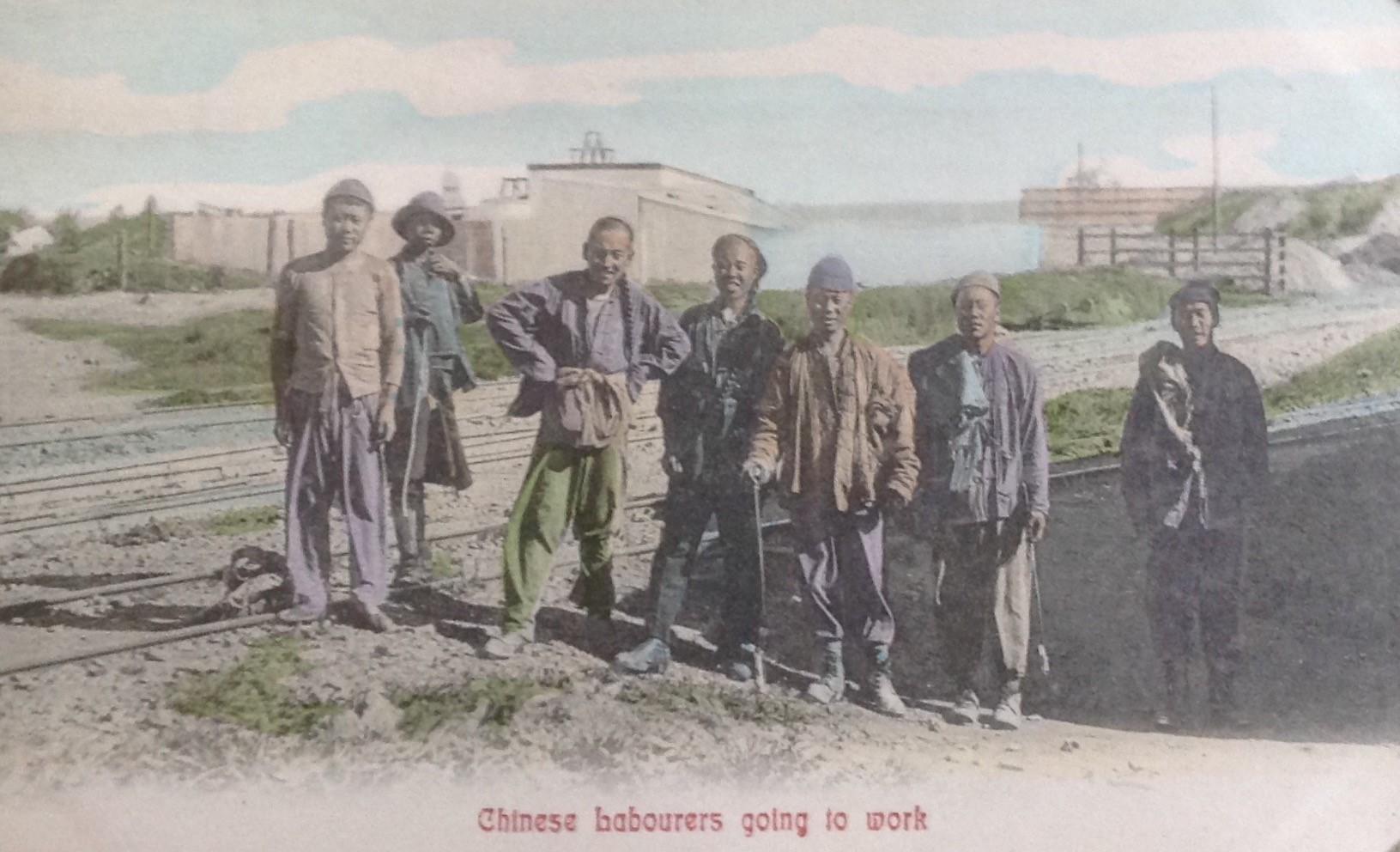

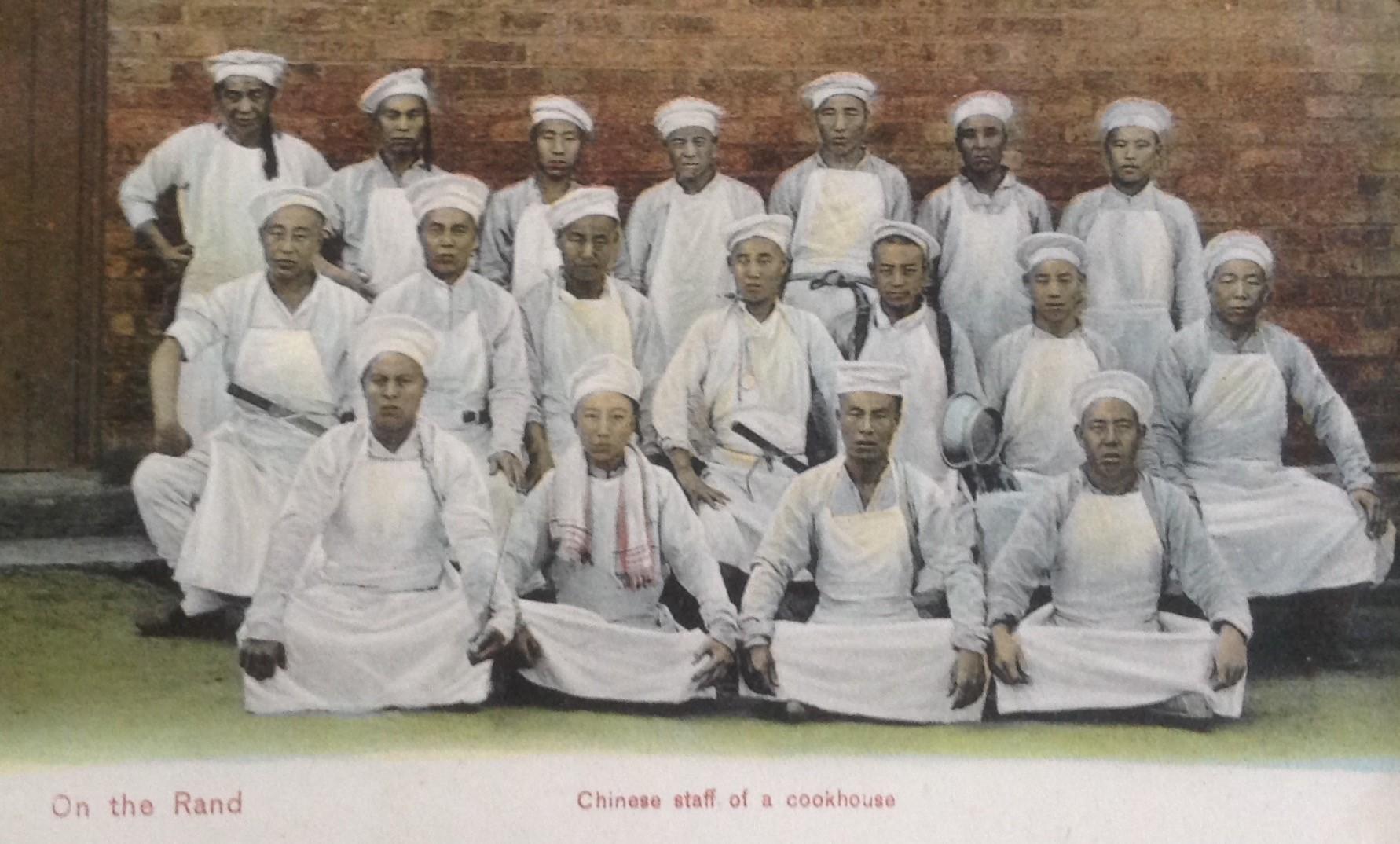

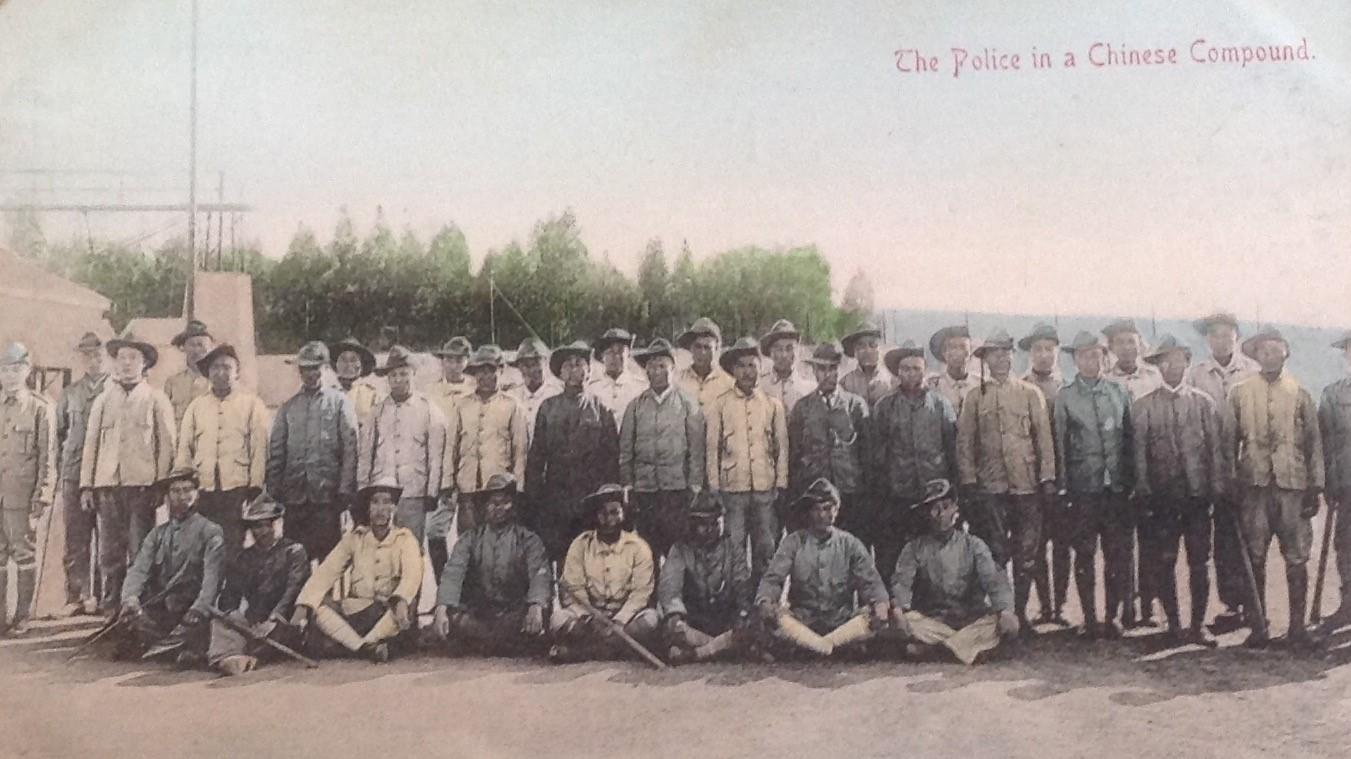

Chinese

A labour shortage at the gold mines on the Rand resulted in the importation of Chinese labour in 1904. This situation, in part, was the result of the Anglo-Boer War (South African War) of 1899 - 1902, which had displaced large numbers of the indigenous population resulting in a labour shortage of around 130,000 unskilled labourers at the mines. The mines had also become unpopular with Black Africans due to attempts to reduce wages to maximise profit margins and the fact that some Black Africans had saved money during the war years to be able to tide them over for a few years.

In December 1903, the Chamber of Mines, the Chamber of Commerce, and the nominated Legislative Council of South Africa recommended that labourers be imported from China on short-term contracts that terminated with compulsory repatriation, resulting in the first Chinese labourers arriving at the Witwatersrand on 19 June 1904. Between 1904 and 1910 there were almost 64,000 Chinese working on the Witwatersrand gold mines near Johannesburg. This measure was successful in increasing the production of gold from mining.

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the police room in the Chinese compound. Card number 2028 was published by Sallo Epstein & Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Chinese labourers on their way to work. Card number 1329 was published by P.S. & C. (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Chinese cookhouse staff. Card number 420 was published by Braune & Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Police based in the Chinese Compound. Card number 2069 was published by Sallo Epstein & Co (circa 1900).

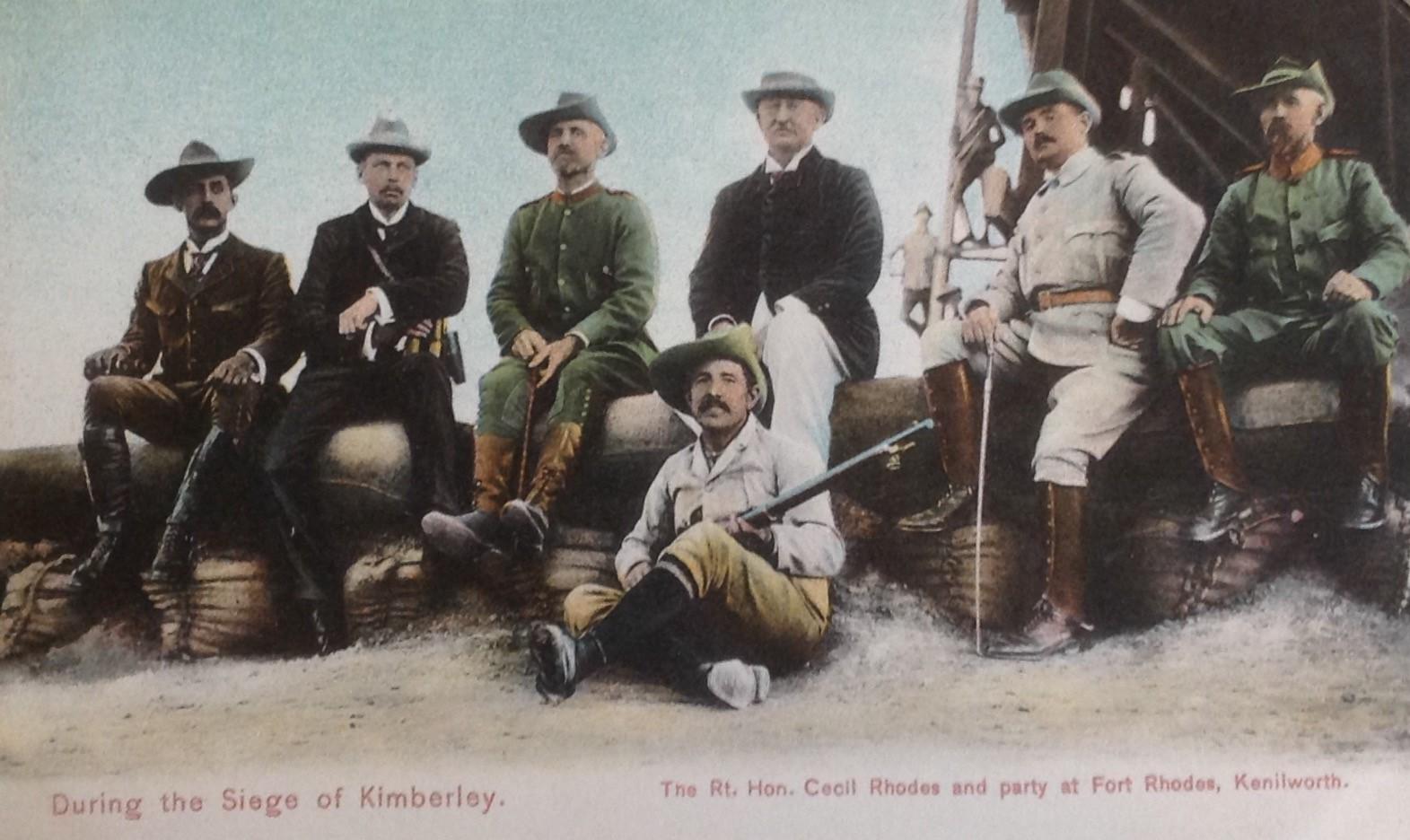

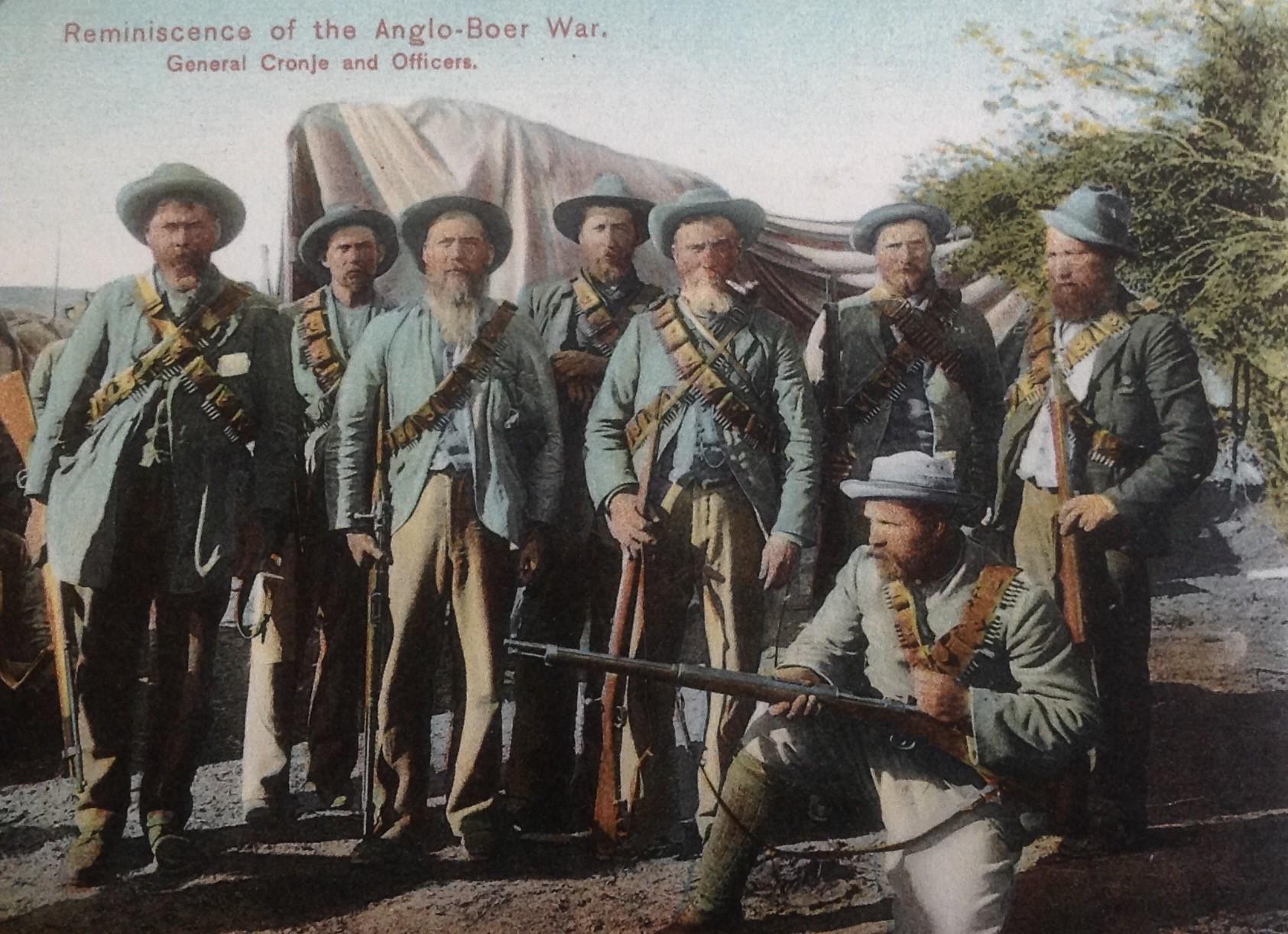

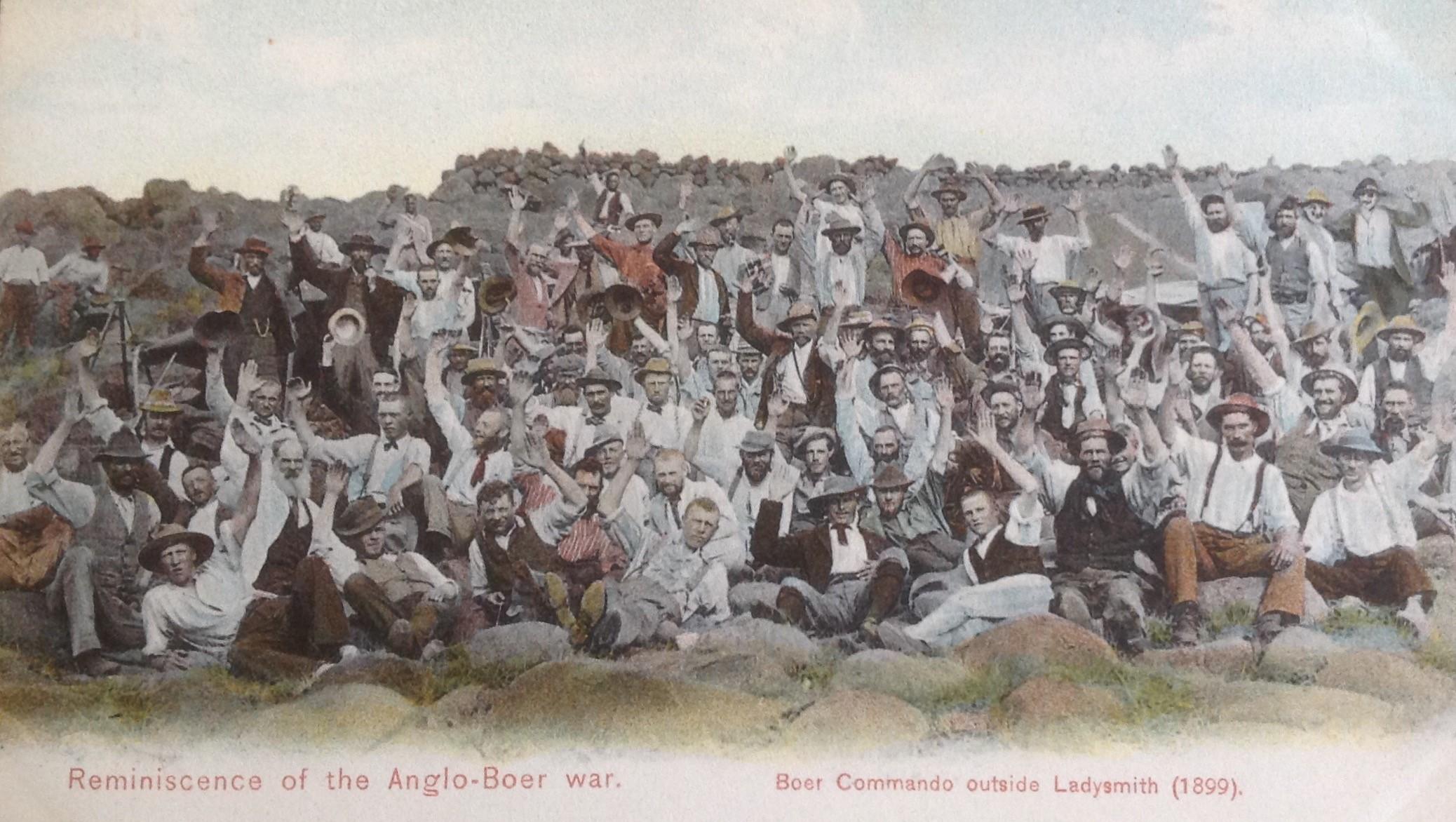

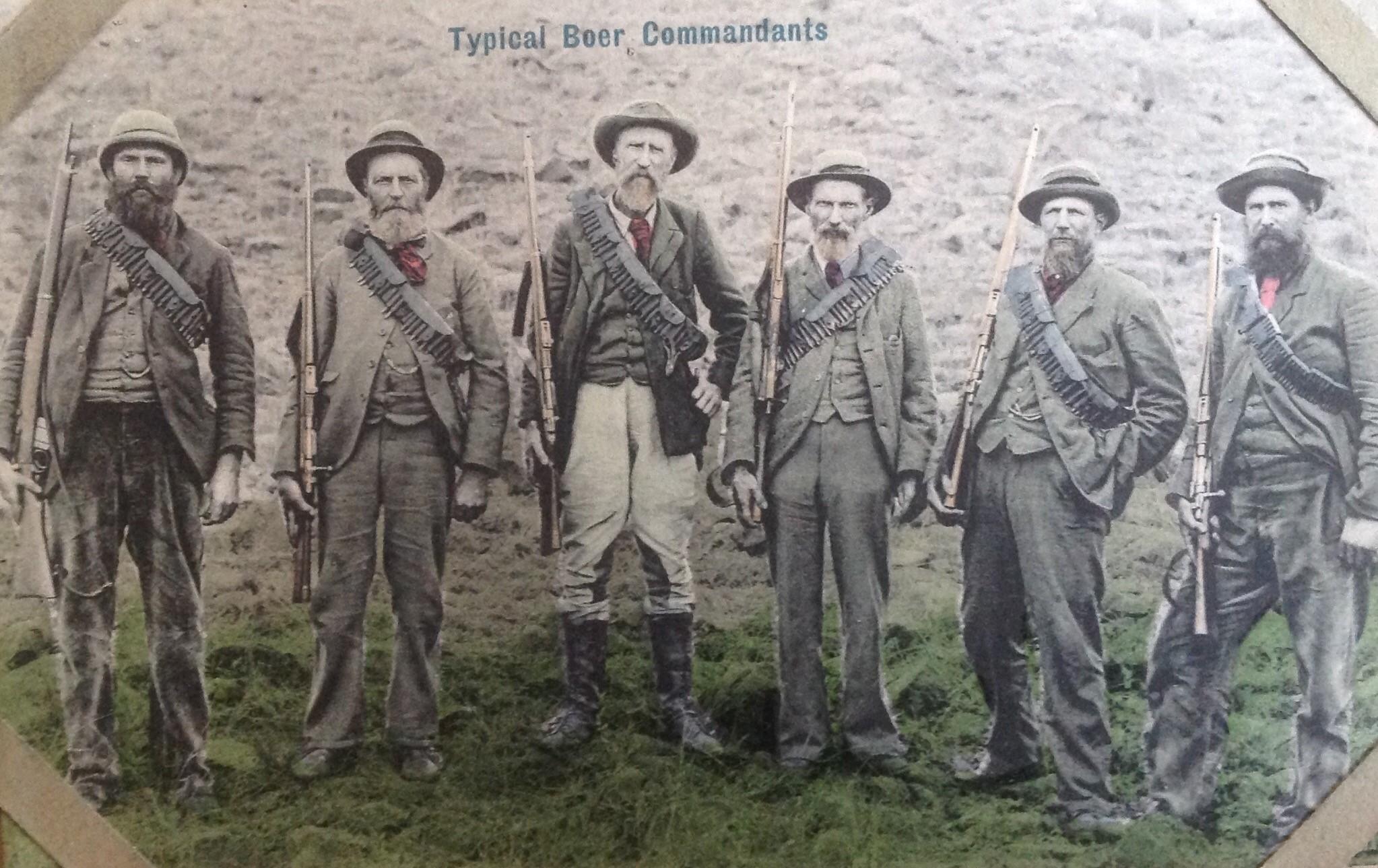

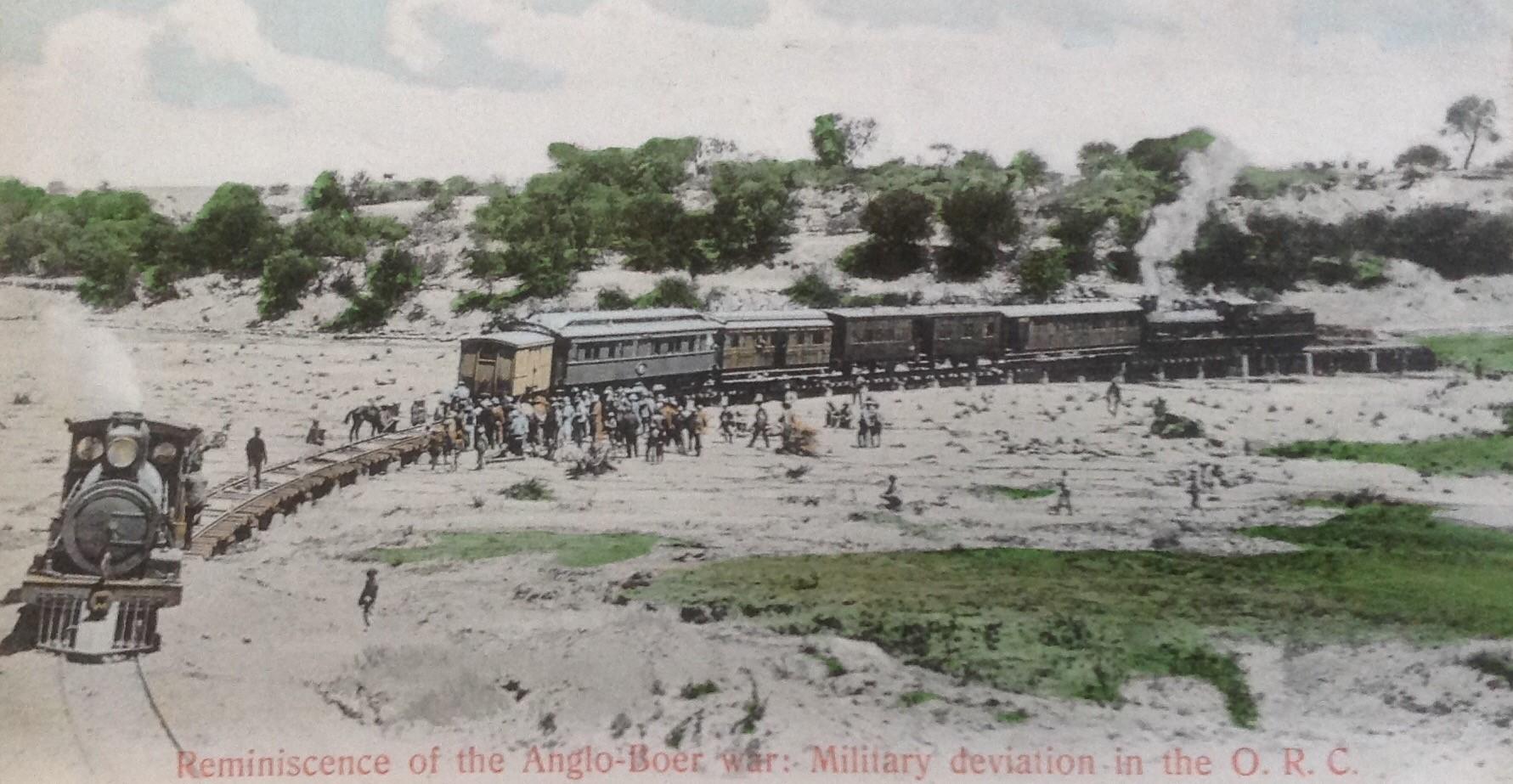

Anglo-Boer War

Although Willis was not present in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer war, he would have been aware of his countrymen being involved in the conflict down south. He most certainly also experienced the societal aftermath in that he arrived in the country the same year peace was achieved between the conflicting parties.

The origins of the Boer War lay in Britain's desire to unite the British South African territories of Cape Colony and Natal with the Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (also known as the Transvaal).

Recognising from the onset that Britain was not seeking a peaceful settlement, the ZAR and its ally, the Orange Free State, resolved to strike first.

On 9 October 1899, the ZAR issued an ultimatum demanding the withdrawal not only of British troops from their borders but of all reinforcements sent to South Africa since 1 June 1899. This ultimatum was rejected and on 12 October the allied republics invaded Cape Colony and Natal, resulting a.

As a result, the bitter colonial war British Army fought a bitter colonial war against the Boers in South Africa between 1899 and 1902.

The Boers soon laid siege to the towns of Kimberley, Mafeking, and Ladysmith and, in December 1899, defeated British attempts to relieve them in the battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso.

'Black Week', as the period of these defeats became known, was a major shock to the British public who were used to hearing of victories throughout the Empire.

Although outnumbered, the Boers were a skilled and determined enemy. After initial setbacks and a prolonged period of guerrilla warfare, the British eventually prevailed, but not without adopting controversial tactics.

Hand coloured Anglo-Boer war picture postcard showing Cecil Rhodes and party at Fort Rhodes in Kenilworth during the Kimberley siege. Card number 2530 was published by Braune and Levy (circa early 1900).

Hand coloured Anglo-Boer war picture postcard showing General Cronje and Officers. Card number 2534 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured Anglo-Boer war picture postcard showing a Boer Commando outside Ladysmith in 1899. Card number 2513 was published by Braune and Levy.

Hand coloured Anglo-Boer war picture postcard showing six Boer Commandants. Card number 2593 was issued by Sallo Epstein and Co (circa 1900). Tinus le Roux’s recent book cover of the Anglo-Boer war in Colour shows the same three men in the centre (2nd, 3rd and 4th from the right).

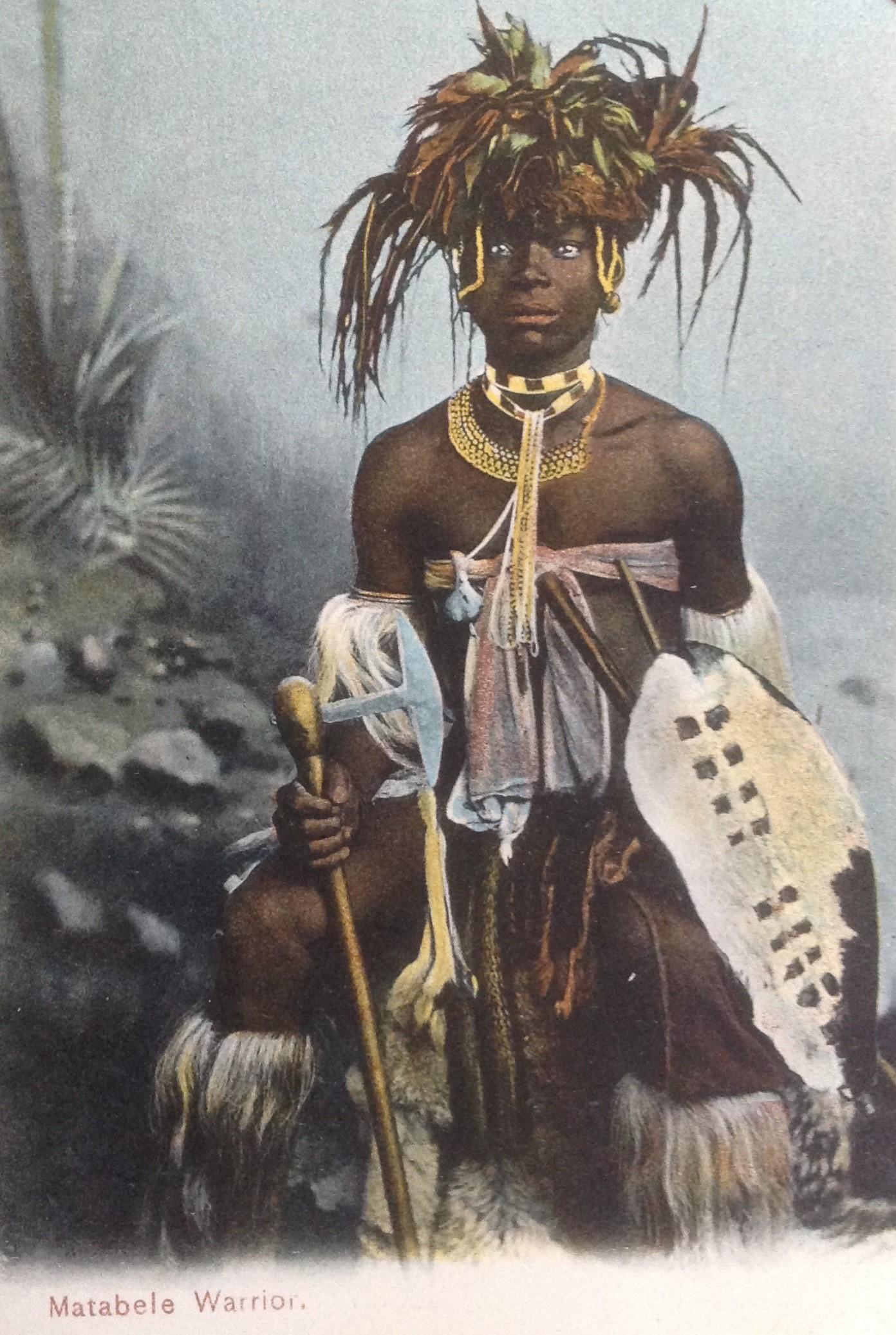

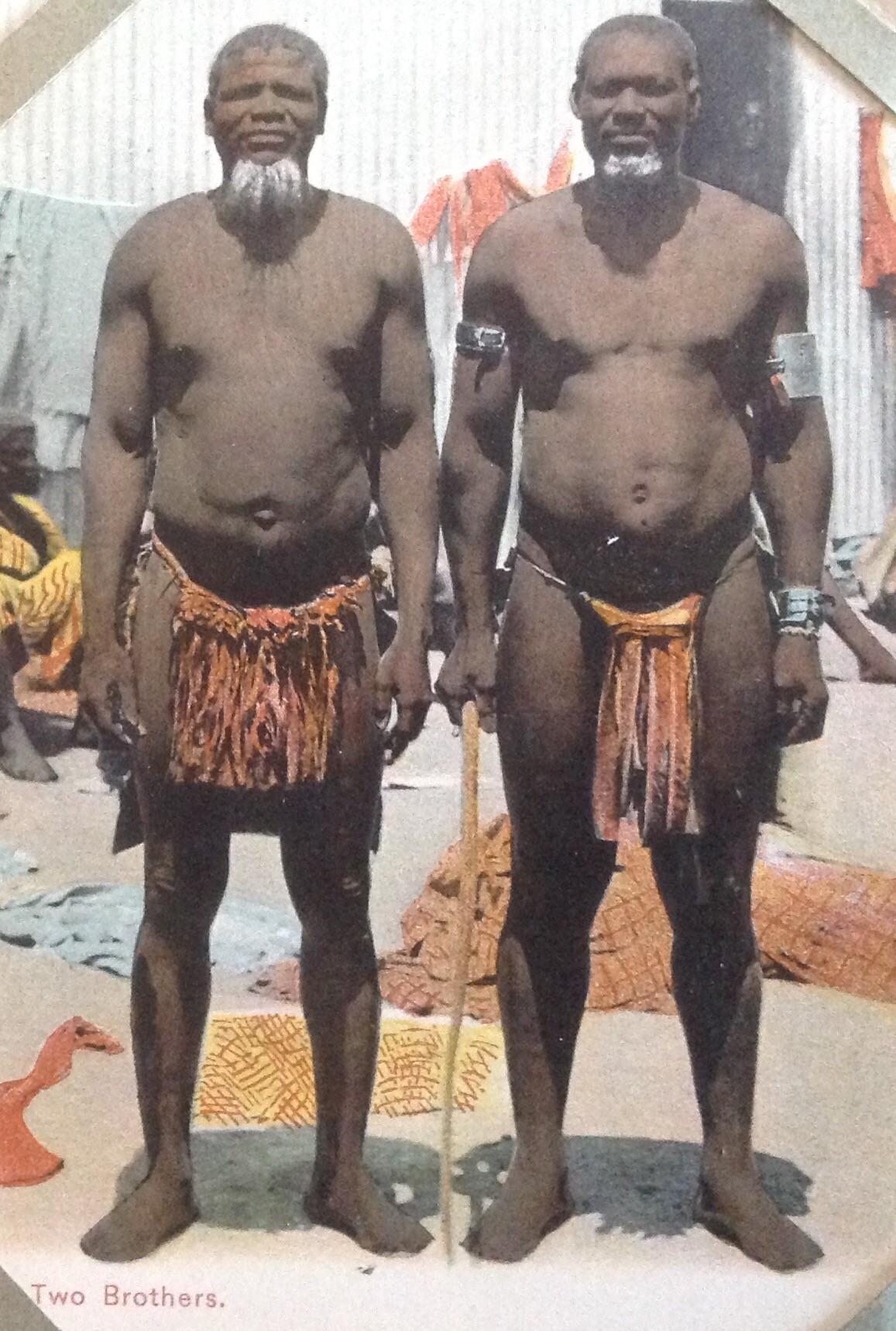

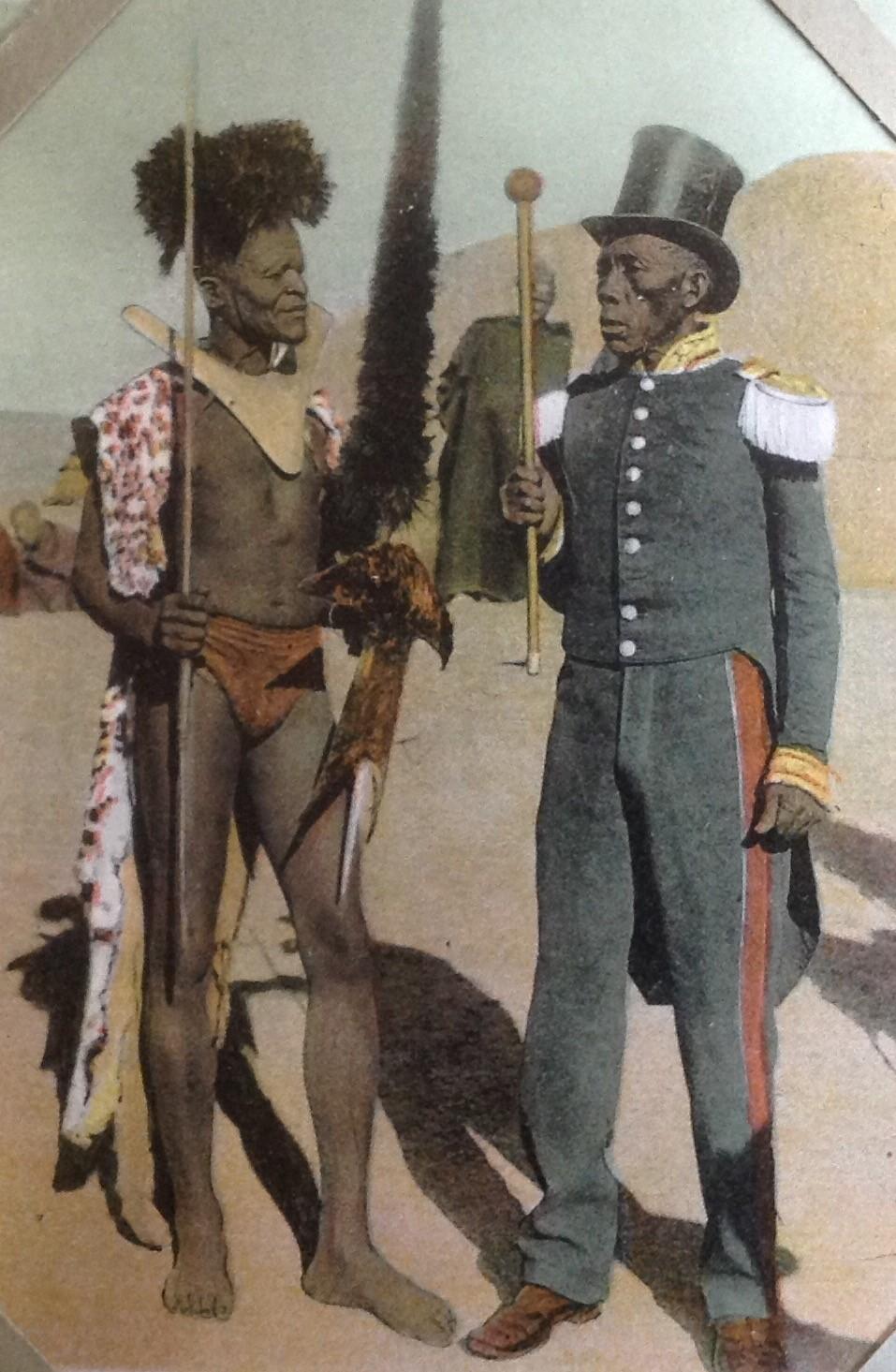

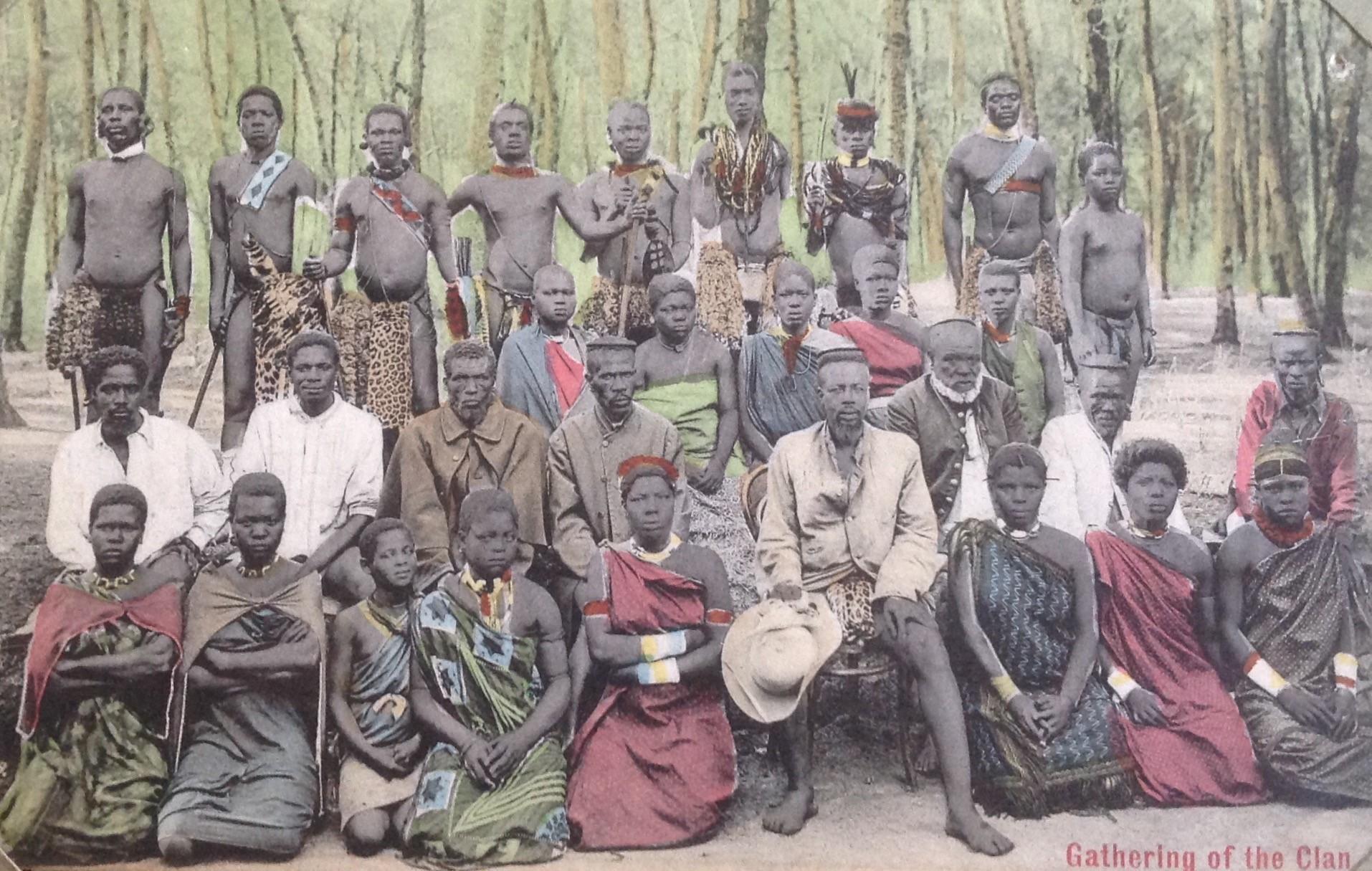

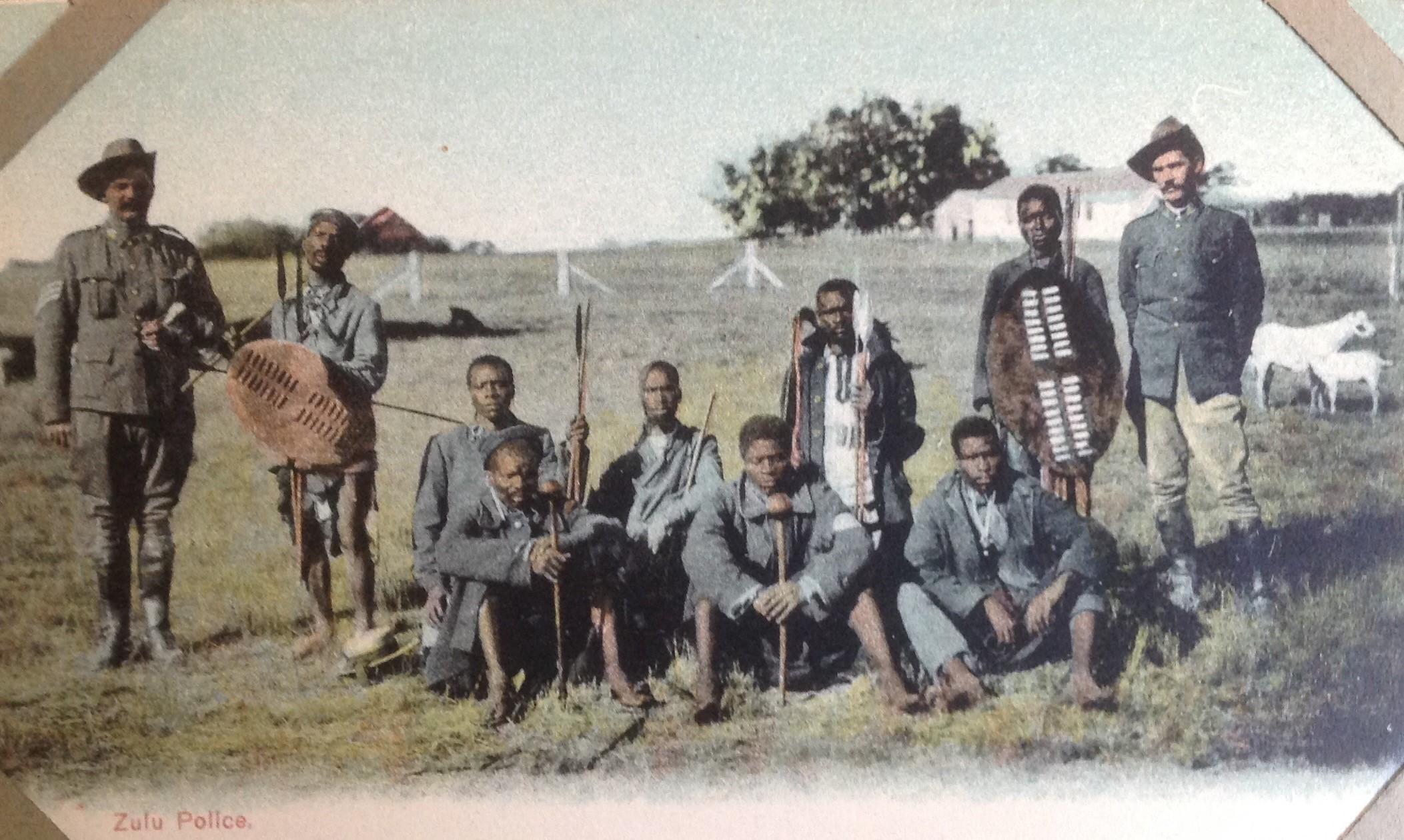

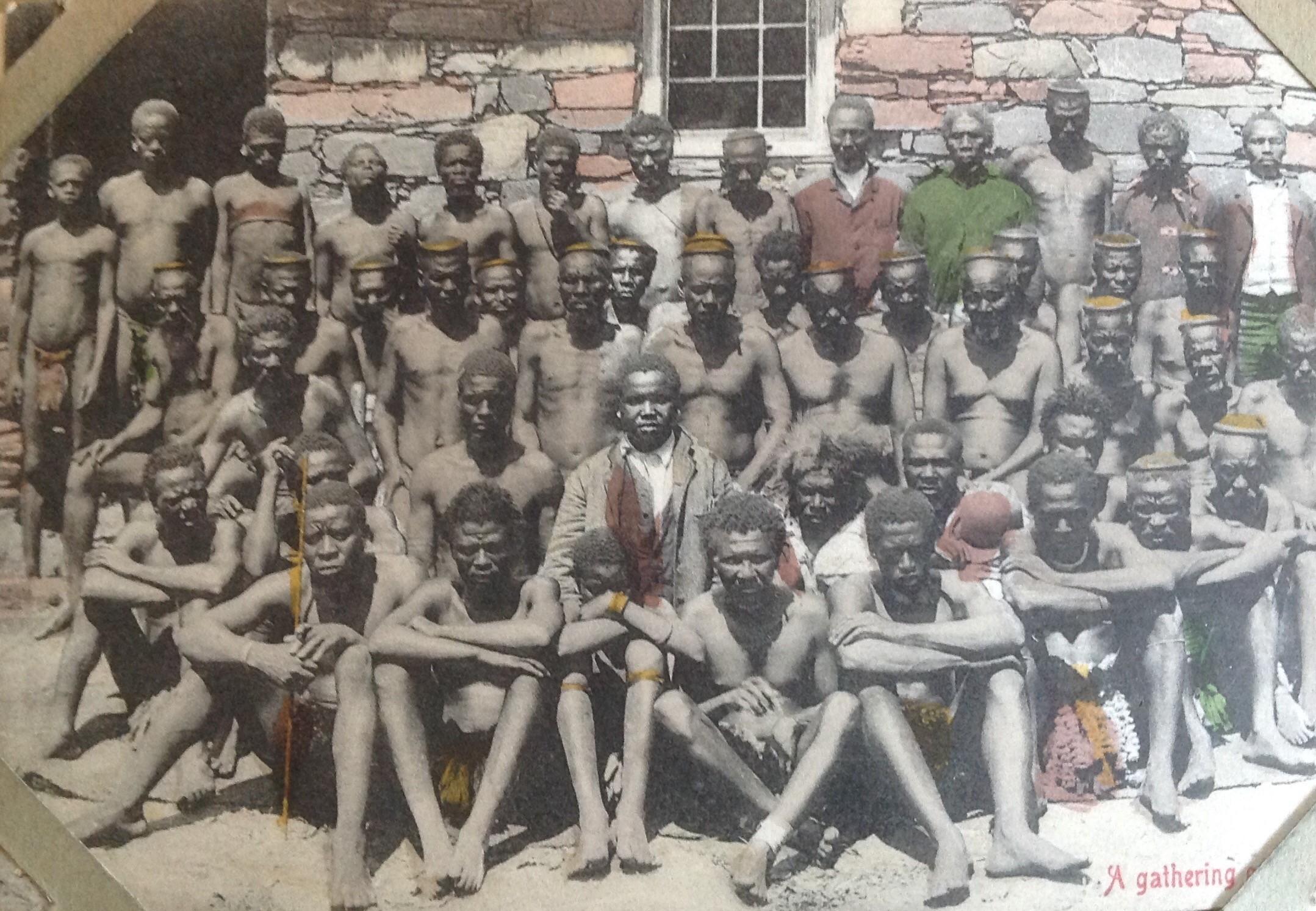

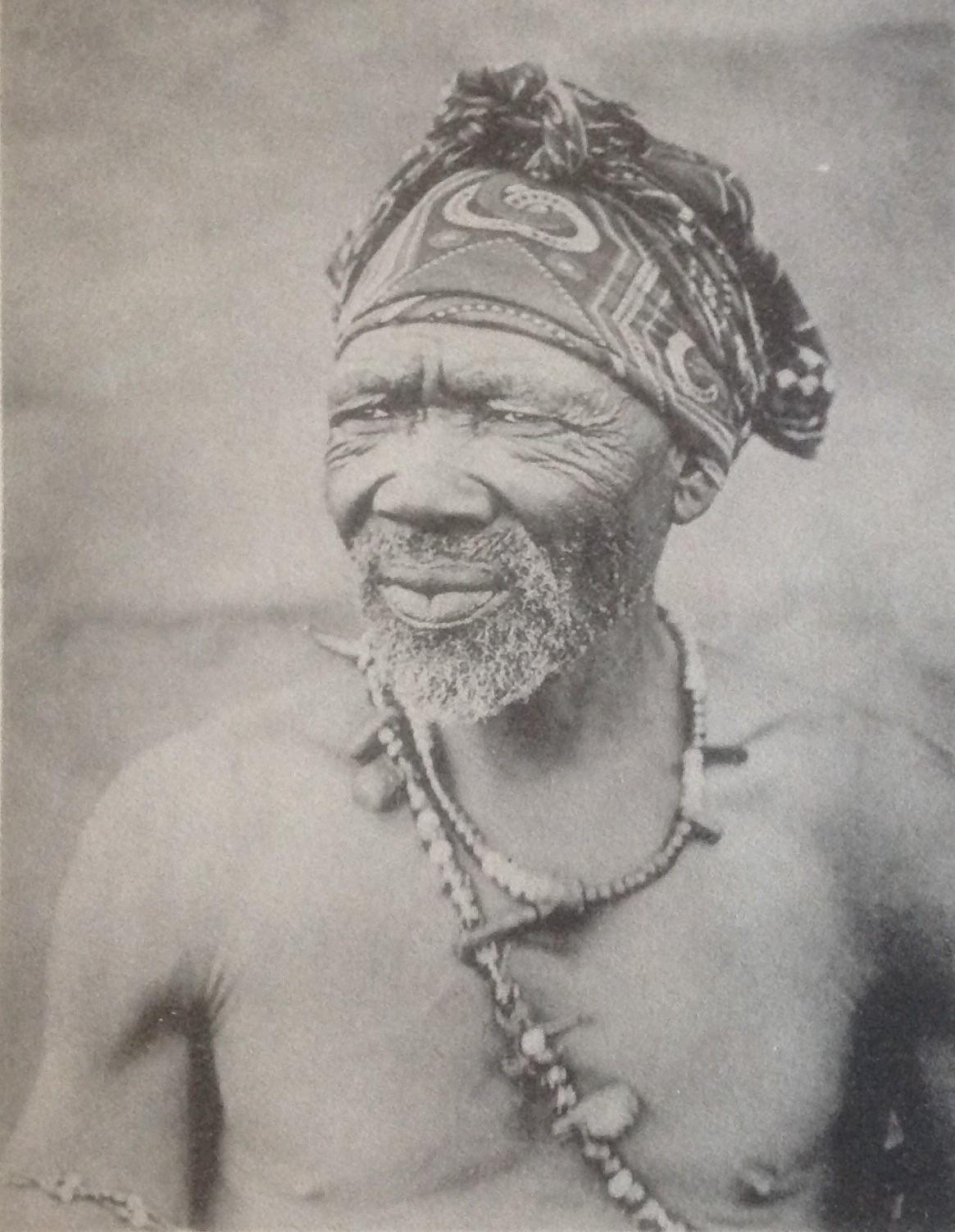

Ethno-photographic images

Ethnographic photography has had a place in photographic history since the invention of photography. Western nations were curious about people in places far away and cultural traditions different from their own, which resulted in photographs of indigenous people being produced since the mid-1840s.

In simple terms, ethno-photography can be defined as photographs of any indigenous culture that is ethnically and culturally different from that of the photographer.

Photographers who focussed on ethno-photography presented their own bias or documentary styles in that the visual and psychological interpretation of the photographer played a vital role in how the culture of the indigenous people was captured.

The photographs produced from the undiscriminating lens rather than the selective human eye, however fudged or posed, possess an inadvertent truthfulness about them. The uniqueness of these images is undeniable – some even have a sense of theatre about them.

Ethno-photographs had a strong colonial influence during the late and early 19th century in that it was often the colonialist photographing the colonised. Photographs ethnic in origin were mainly captured by Europeans living in or visiting South Africa. The primary purpose and intent of the “picture- postcard photographer” was to capture images for commercial reasons.

Some of the images contained in the album are condescending in today’s terms.

Hand coloured picture postcard of Matabele (Ndebele from Zimbabwe) . Card Number 1340 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing two Zulu brothers. Card number 1313 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Basutoland chief and warrior. Card number 1410 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing a Fingo Witchdoctor and his wife. The Xhosa speaking Fingos (or Mfengu) are from the Eastern Cape. Card number 1349 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing a Zulu gathering. Card number 1931 was published by Sallo Epstein and Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Zulu police. Card number 6453 was published by RO Fusslein (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing a Zulu gathering. Card number 2128 was published by Sallo Epstein and Co (circa 1900).

Picture postcard showing a Natal medicine man. Publisher unknown

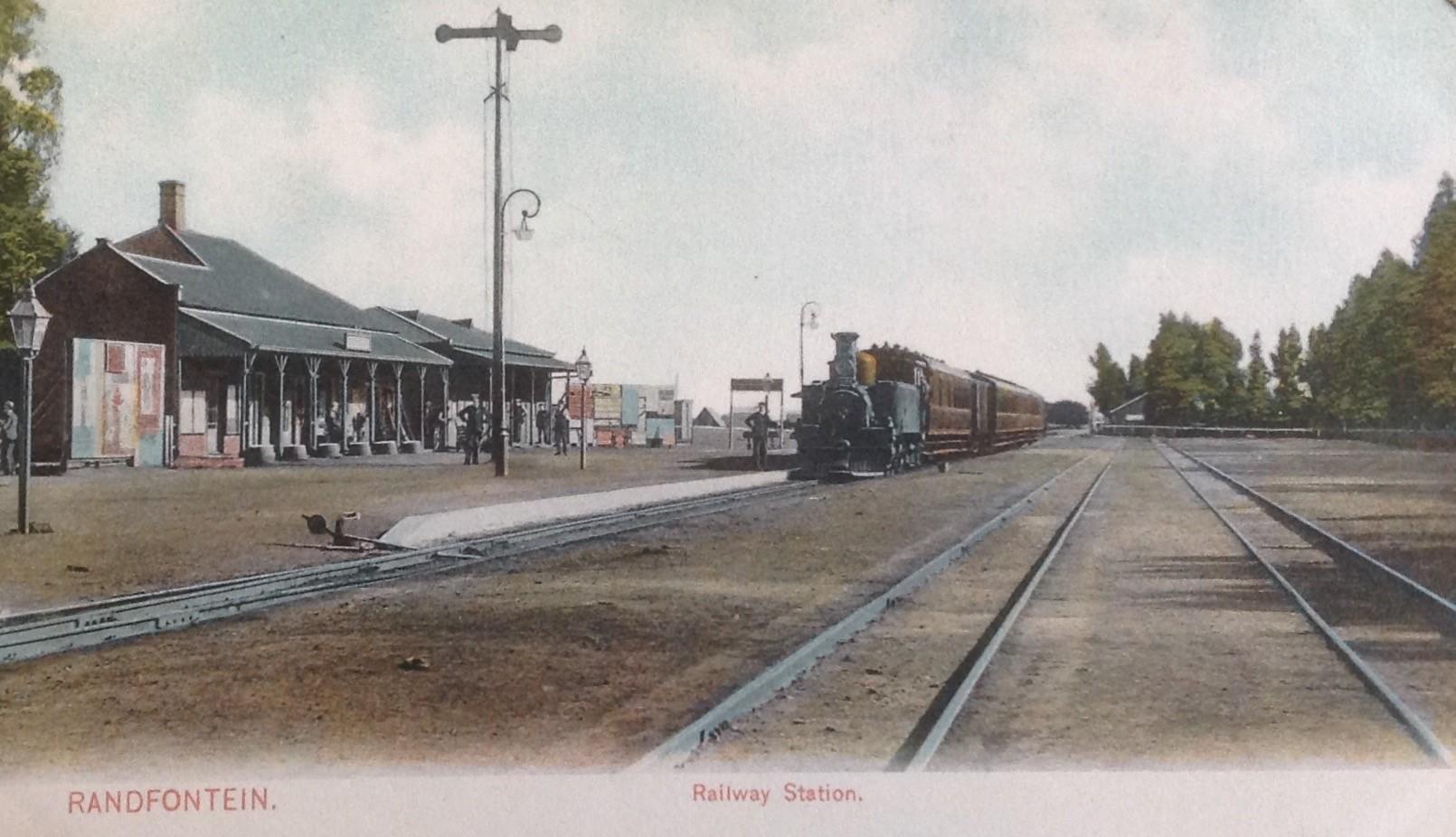

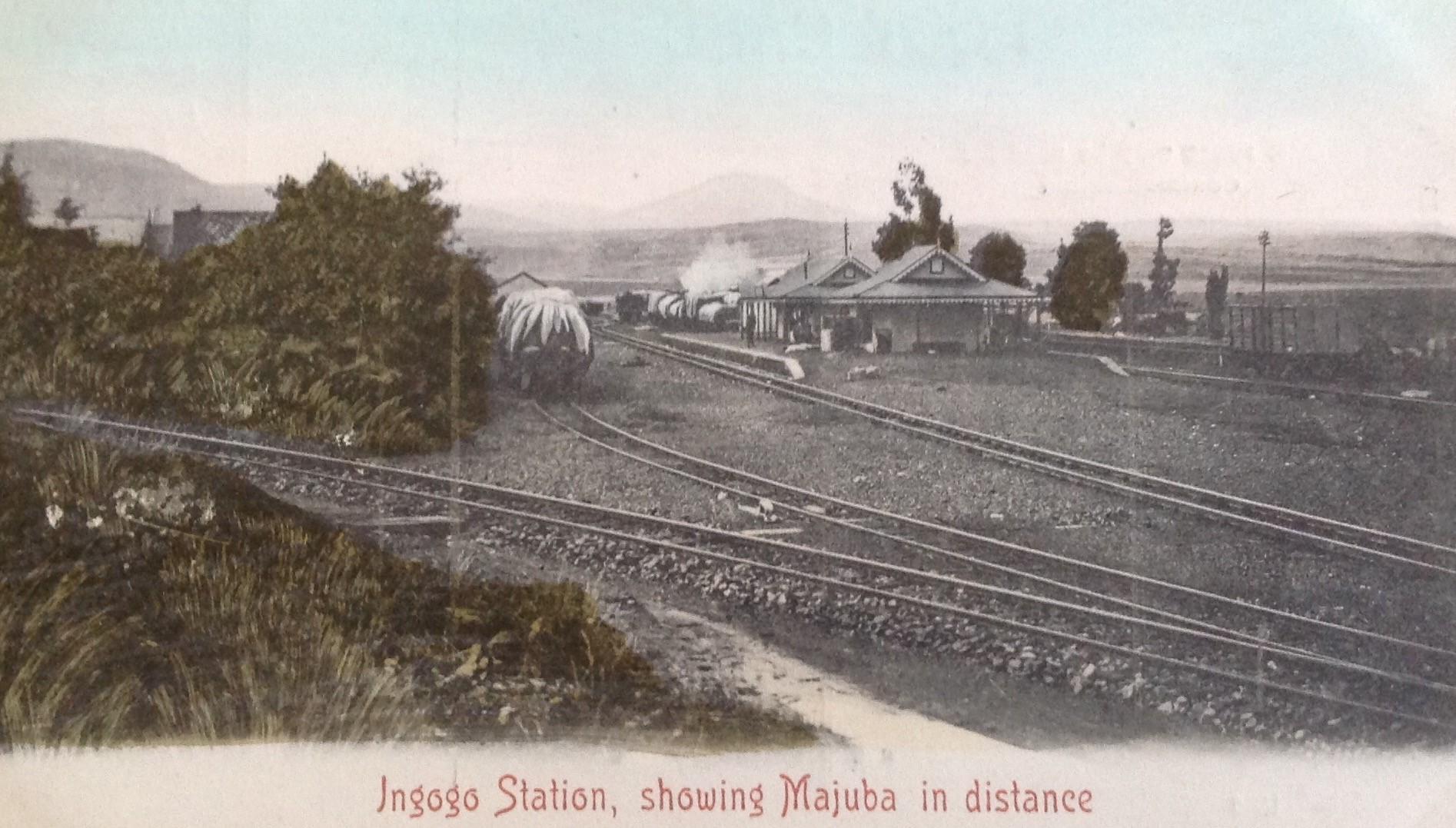

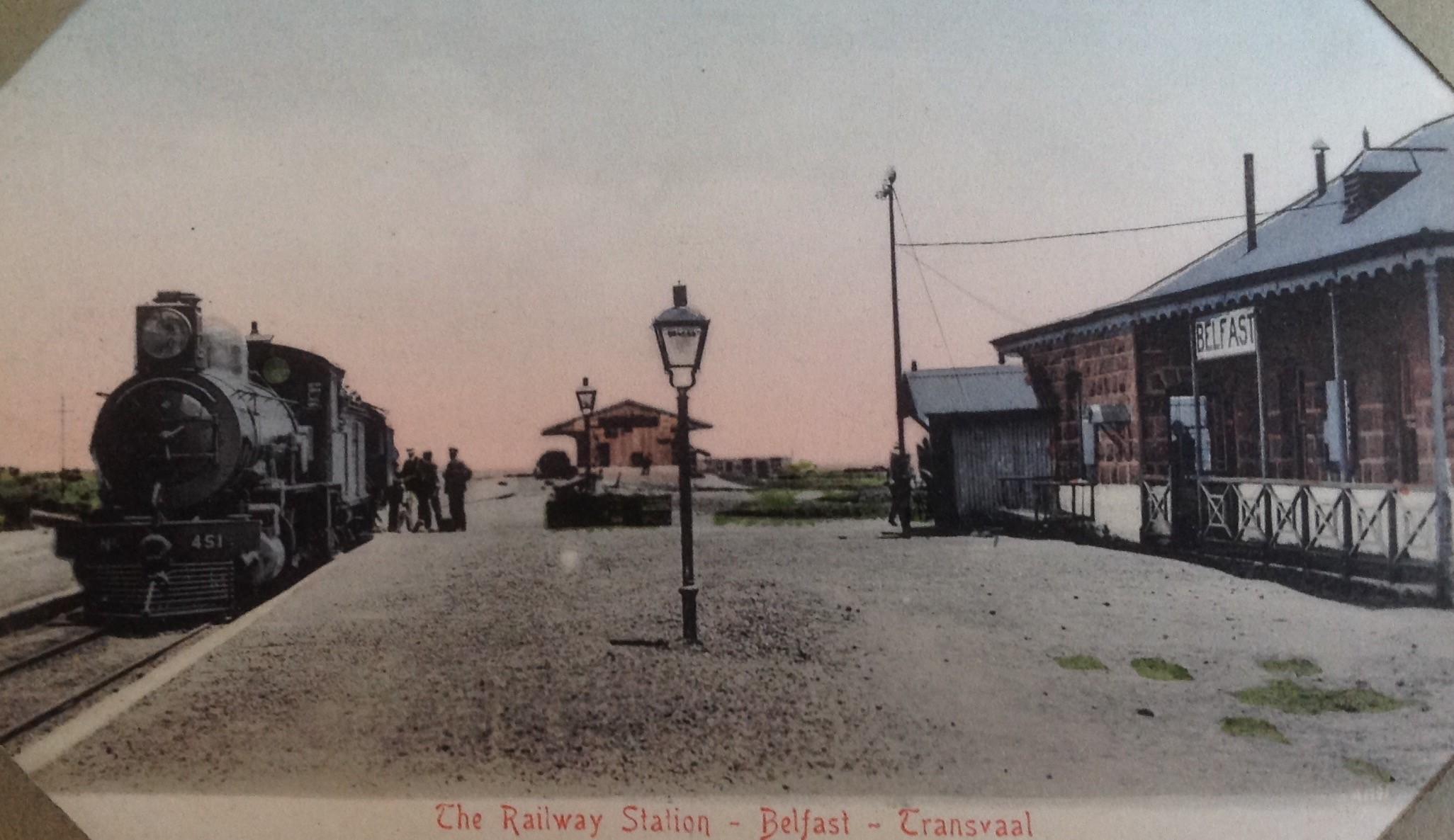

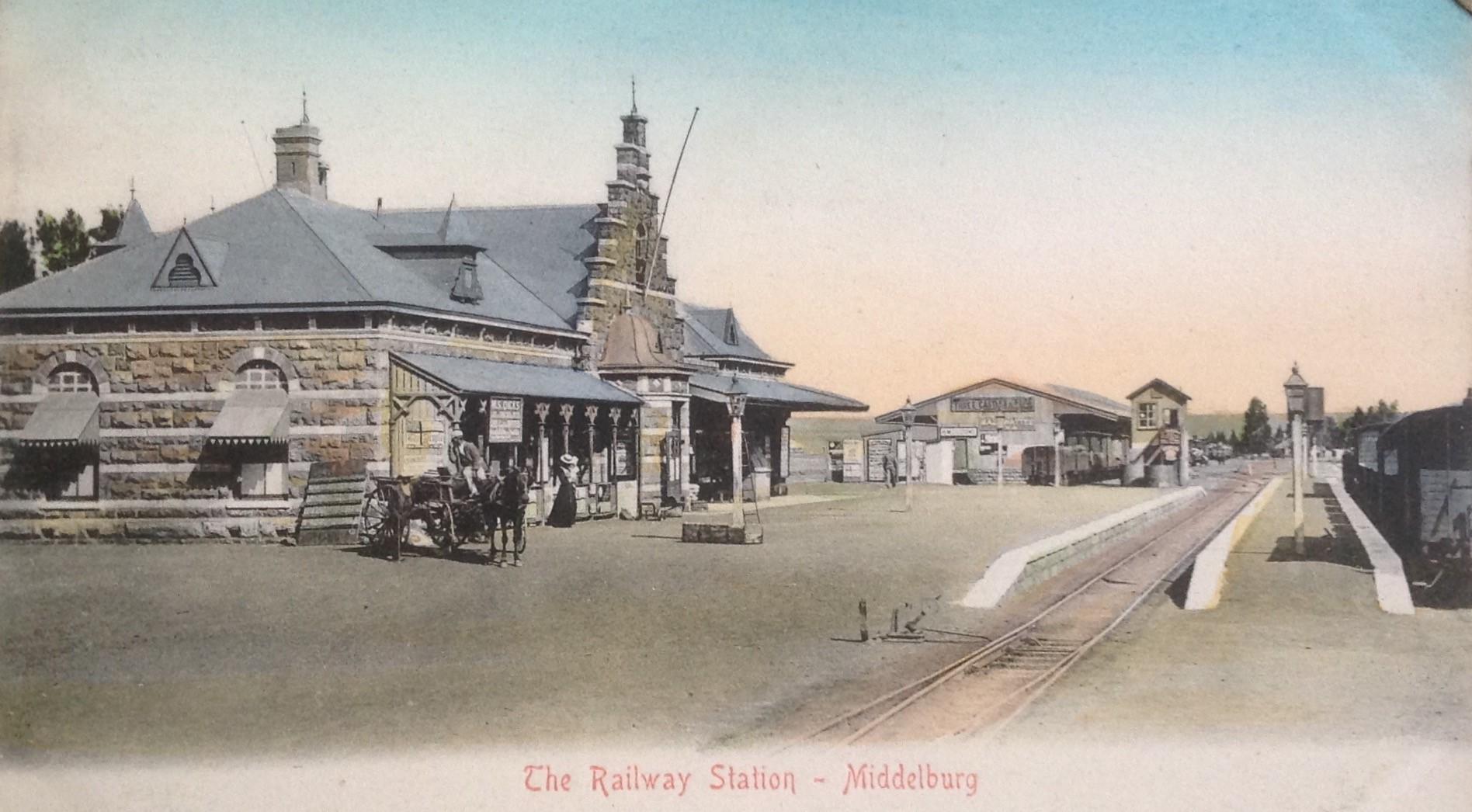

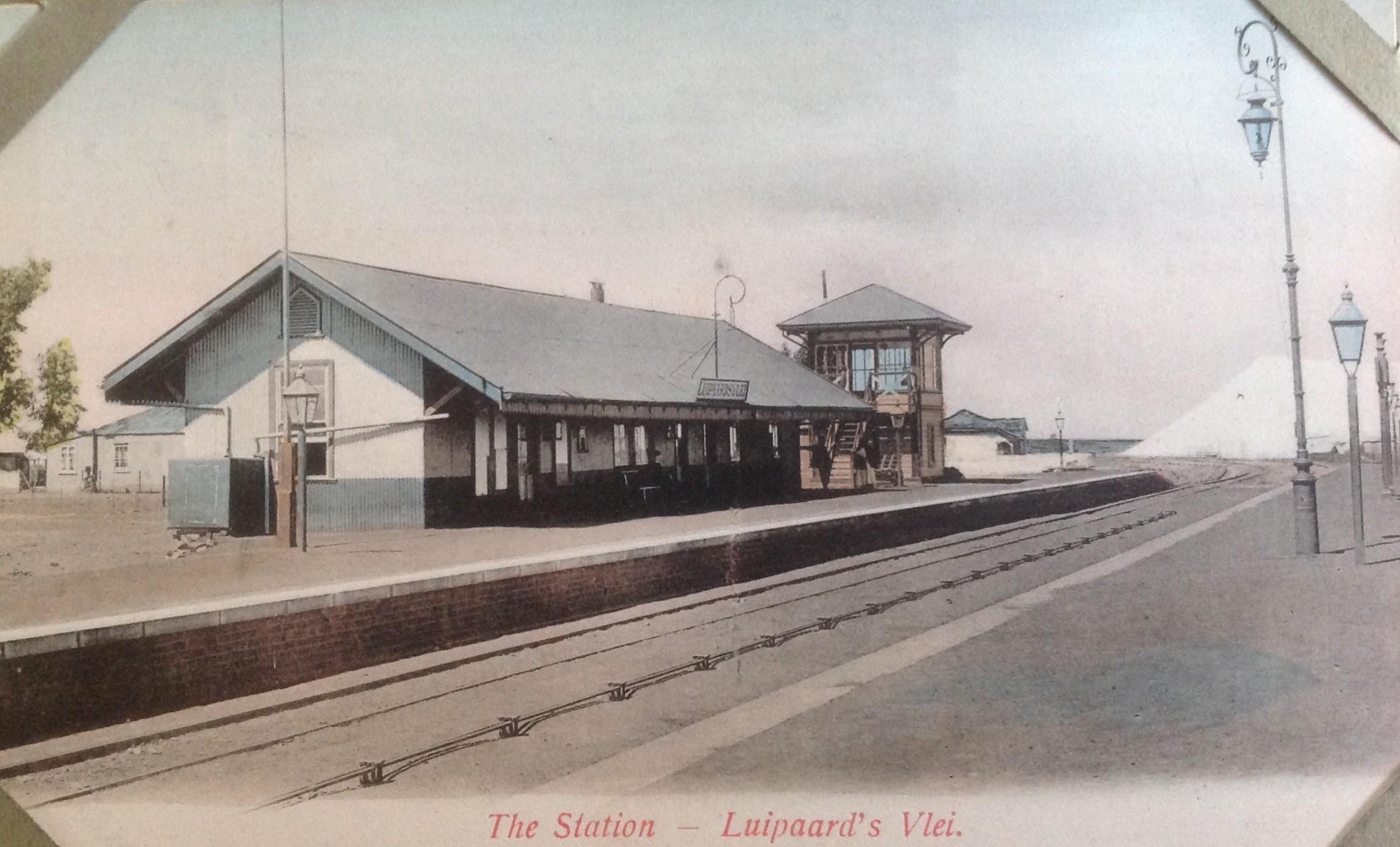

Railway stations

The first railway in South Africa was from Cape Town to Wellington and was worked by a small locomotive in 1859.

The first passenger-carrying service was a small line of about 3.2 kilometres built by the Natal Railway Company, linking the town of Durban with Harbour Point which opened on 26 June 1860.

After the formation of the Cape Government Railways in 1872, the Cape railway construction began a massive expansion.

In the north, in the independent South African Republic, railway construction was done by the Netherlands-South African Railway Company (NZASM), which constructed two major lines: one from

Pretoria to Lourenço Marques in Portuguese East Africa Colony, and a shorter line connecting Pretoria to Johannesburg.

The A national rail network was largely completed by 1910. Upon the merger of four provinces to establish the modern state of South Africa in 1910, the railway lines across the country were also merged. South African Railways and Harbours (SAR & H) was the government agency responsible for, amongst other, the country's rail system.

Many of the railway stations as they appear on the picture postcards are sadly no longer operational or in existence, confirming the value of these historical images.

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Randfontein railway station. Card number 1618 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing Ingogo Station with Majuba in the distance. Card number 1500 was published P.S. & C. (circa 1900).

Hand coloured Anglo-Boer war picture postcard showing a military deviation in the Orange River Colony. Card number 2527 was published by Braune and Levy (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Johannesburg Electric Railway Shed. Card number 2554 was published by Sallo Epstein & Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Grahamstown railway station. Unnumbered card was published by Sallo Epstein and Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Belfast railway station. Card number 1345 was published by Sallo Epstein & Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Middelburg railway station. Card number 1354 was published by Sallo Epstein & Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Luiperd’s Vlei railway station. Card number 529 was published by Sallo Epstein & Co (circa 1900)

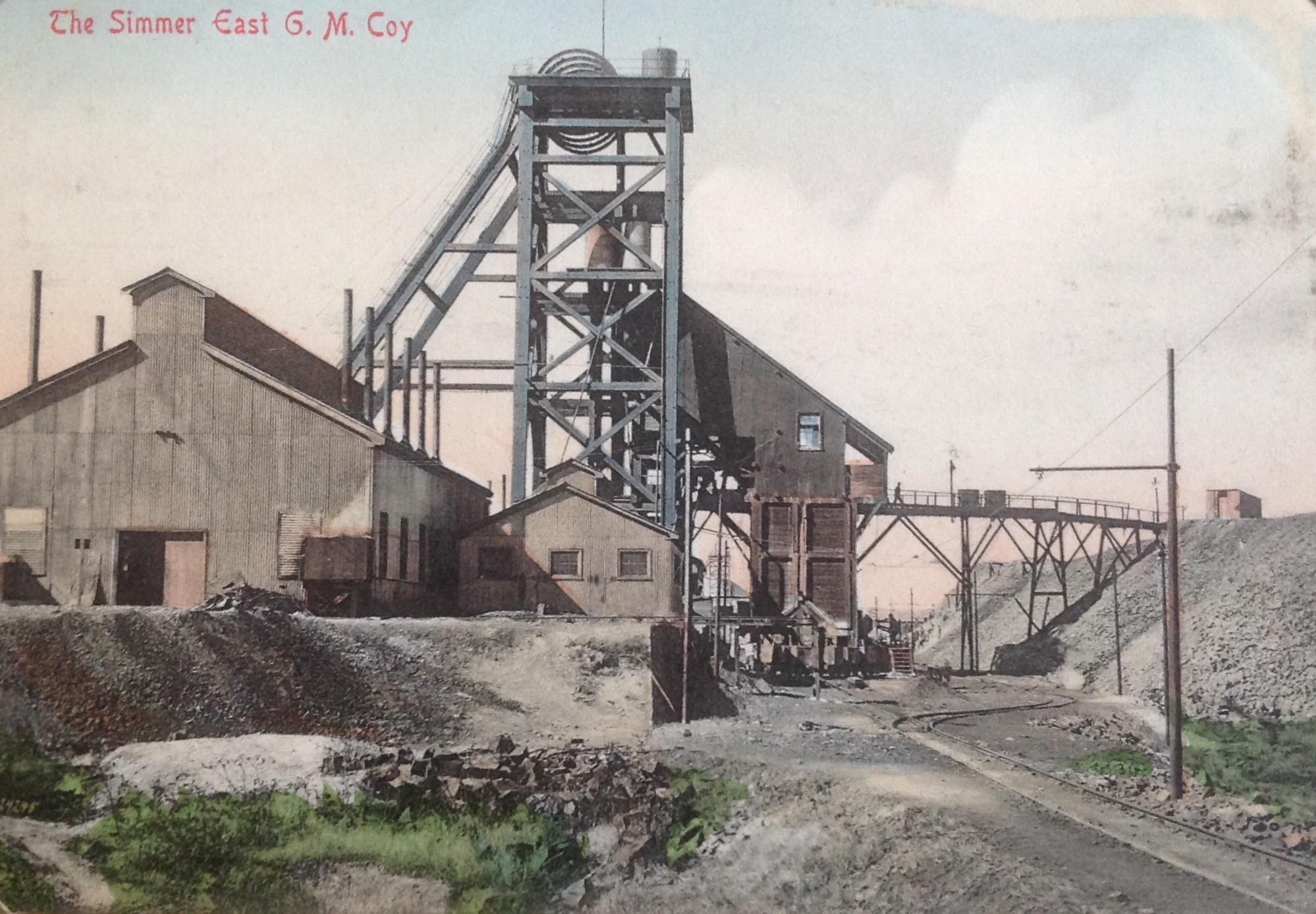

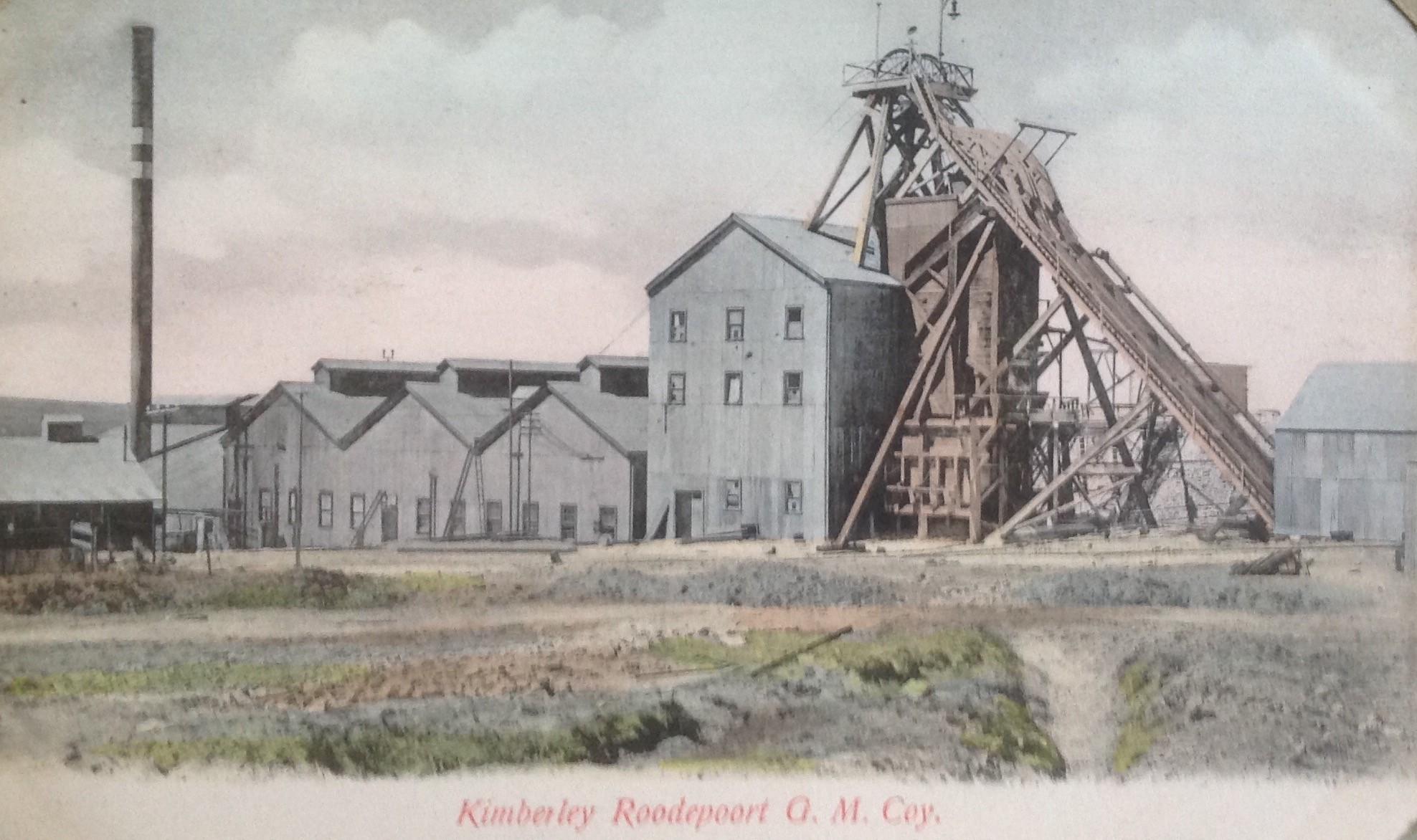

Mining

The Witwatersrand Main Reef eluded searchers until 1886, when George Harrison, an Australian prospector, chanced upon an outcropping on a farm called Langlaagte.

By mid-1886 an army of diggers had descended on the Witwatersrand, hacking away with picks and shovels along a line that soon stretched 40 miles west to east. In response to this influx, the government of the Transvaal, the small Boer republic under whose jurisdiction the Witwatersrand fell, dispatched two men, Vice President Christiaan Johannes Joubert and Deputy Surveyor-General Johann Rissik, to inspect the goldfields and identify a suitable city site. The new city was called Johannesburg, apparently in their honour.

As the scale of the gold deposits became apparent, Johannesburg became the 19th century’s last great boomtown. Fortune hunters from as far afield as Australia and California joined skilled Cornish and Welsh miners, who brought to South Africa a strong trade union tradition. Destitute Afrikaners, driven from their rural homes by debt and drought, clustered in slums such as Brickfields and Vrededorp. Black people from every corner of the southern-African subcontinent migrated to the city, often in large ethnic cohorts, adding a dozen more voices to the cultural and linguistic babel. Most Black people worked in the mines, completing six- and nine-month contracts before returning to their rural homes. Others settled permanently in the swelling city, carving out niches as rickshaw drivers, domestic workers, and washermen. By 1896 Johannesburg had expanded to a city of more than a hundred thousand people.

The rest is history.

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Simmer East gold mine coy. Card number 2122 was published by Sallo Epstein and Co (circa 1900).

Hand coloured picture postcard showing the Kimberley Roodepoort gold mine coy. Card number 547 was published by Sallo Epstein and Co (circa 1900).

Closing

The fact that Willis had such an extensive South African postcard collection also means that he can be referred to as an early South African deltiologist.

The exceptional find, as described above, raises several additional questions.

Willis’ passion for photographs was obvious. Did Willis also collect South African-themed stereoviews and magic lantern slides? My hypothesis is that he did. These were not images that could be collated into a photo album. Where did these images end up eventually? Also, did he construct more than just the two albums? Again, I would suggest that he did.

Whilst the unique Willis photograph collection stands out, Willis was not the only early photo enthusiast. Many citizens collated photographs and placed them in albums at the turn of the 19th century. In the process of completing this article, I stumbled upon another historic photograph album of the same era at a local car-boot sale. This photo album was constructed by a local land surveyor, who seemingly worked on early South African railway line expansions and captured photographs where ever he found himself in the country at the time.

Whilst the Willis family could not be traced, I am immensely grateful that they have not elected to bin the two albums, like so often happens.

These albums somehow ended up with a Pretoria-based antique dealer who has full appreciation for their historical value resulting in them ending up with a contemporary philaphotographologist some 100 years later.

What was left of the tram shed in Port Elizabeth following a flood (circa 1904)

Collapsed bridge following a flood in Daspoort, Pretoria in 1904

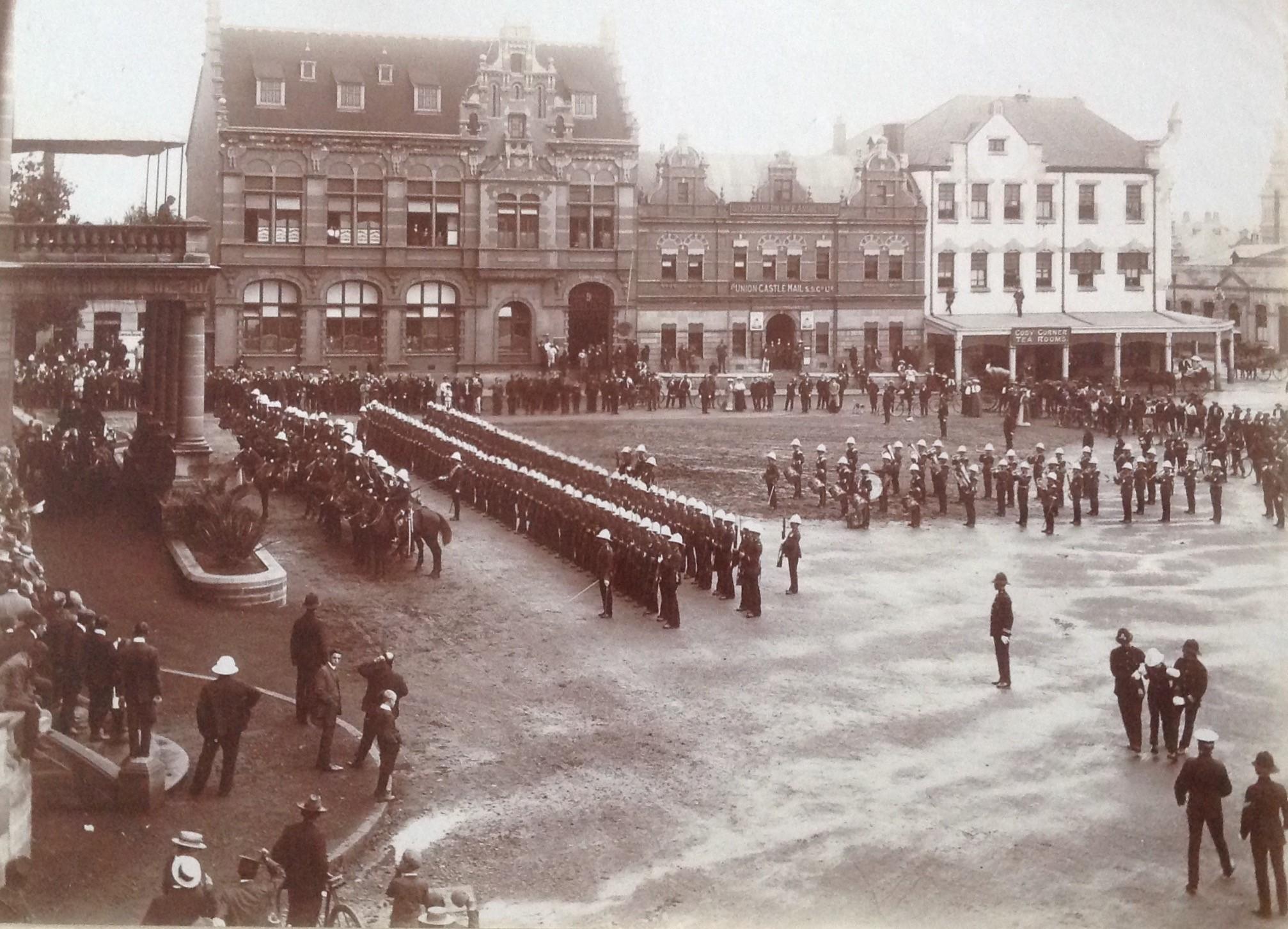

King’s Levee (ceremony) in front of the Government building (Raadzaal) – Pretoria 1904. Willis recorded the names of 4 of his fellow police colleagues who assisted the fainted soldier on the right. The men on either side of the soldier are Constables Shea and Balharry with Sgt. McDonald (far right) and Superintendent Montgomery (second from right) looking on. In the background the Netherlands Bank and Union Castle/Southern Life buildings can be seen.

Trooping the colours on Pretoria Church Square with the Palace of Justice building in the background (1904).

Double decker tram in Johannesburg snowstorm during 1909

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2018). Early Ethno-photography and the picture postcard – A South African perspective (www.theheritageportal.co.za)

- Rackham, I. (2022). What do you call a person who takes pictures? (www.qa.answers.com)

- Spencer, S. (Unknown). The ‘British-Imperial’ model of administration: Assembling the South African Constabulary. University of Virginia. Scientia Militaria (http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za - page 92 – 115)

- Unknown (extracted September 2023). Arrival of Chinese labourers in South Africa. (www.sahistory.org.za)

- Unknown (extracted September 2023). Johannesburg Miners’ strike 1913. (www.sahistory.org.za)

- Unknown (extracted September 2023). Boer War. (nam.ac.uk/explore/boer-war). National Army Museum

- Unknown (extracted September 2023). History of Johannesburg. The early period, 1853 – 1930 (www.britannica.com/place)

- Wikipedia (extracted September 2023). Railway Transport in South Africa. (Wikipedia.org)

- Wikipedia (extracted September 2023). South African Constabulary. (Wikipedia.org)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.