Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is a pity that artistically designed bookplates or ex libris as they are referred to in Europe, have fallen into relative disuse in South Africa. Antiquarian bookdealers have long known that a well-designed bookplate adds not only to the appearance and interest, but also to the monetary value of a rare book.

By him who bought me for his own,

I’m lent for reading leaf by leaf;

If honest you’ll return the loan,

If you retain me you are a thief.

How many of us have uttered similar sentiments when lending out a book, suspecting it will not be returned? This is exactly what a bookplate is supposed to prevent.

But what is a bookplate, or ex libris?

In plain terms a bookplate is a print, drawing or watercolour designed by an artist, usually affixed on the inside cover of a book, as identification mark of its ownership. Over time bookplates have become objects of interest and desire to collectors. Many bookplates are works of art, owned by prominent people and often reveal their interests and characteristics.

The Latin phrase ‘ex libris’ meaning, ‘from the books of’, is far more appealing than the practical term ‘bookplate’, but both terms are usually applied interchangeably.

In Europe, the making of ex libris started shortly after the beginning of book printing, somewhere around the last quarter of the fifteenth century. The inspiration for making them arose from the medieval practice of identifying the ownership at the front of illuminated Books of Hours (prayer books). Even though the discovery of the movable print by Johannes Gutenburg around 1440 AD in Mainz immeasurably increased the number of books in circulation, the initial print runs were small hence early printed books remained very valuable. For example, only about 180 copies of Gutenburg’s famous Bible were printed in 1455. Book owners therefore started commissioning artists to design woodcuts with images to proclaim their ownership. Initially the images were mostly the owners’ coat of arms. At this time lineage was considered to be very important and a coat of arms provided the identification of the owner and the family members who would one day inherit the book. According to Hopkinson, bookplates from about 1500 to 1850 AD tended to be mainly armorial or heraldic in design.

Towards the mid-nineteenth century the demand for bookplates started to extend to the educated and increasingly well off middle classes who did not possess any coats of arms or images of heraldry. Church ministers, attorneys, senior military officers, academics, politicians and successful businessmen etc., were all attracted to the idea of having personalized bookplates. During this period, bookplates in the pictorial style, which reflected the owners’ life and interest, became increasingly popular. Punning also became a common theme whereby various elements in a design were combined to form the owner’s name.

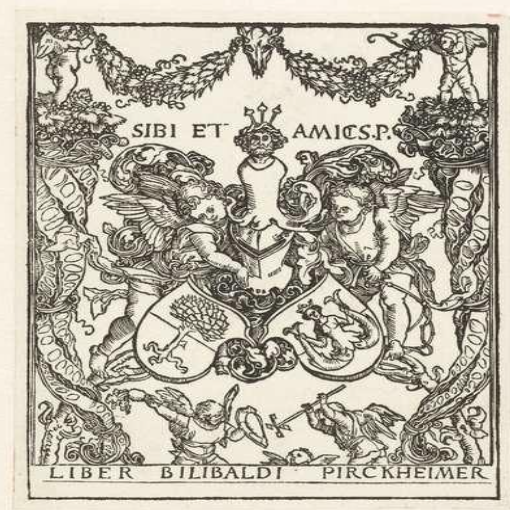

Albert Dürer (celebrated artist of the German Renaissance) himself designed bookplates and one of his best known was to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer, a Nuremburg jurist of some note, whose portrait he engraved on copper in 1524. The bookplate and there is little doubt that it is one, given the words ‘Liber Bilibaldi Pirckheimer’, probably dates from about the same time (see main image). Hardy describes this bookplate as follows, ‘It is a very striking book-plate. A strangely large helmet, on which is placed an equally large crest, surmounts a pair of shields. The dexter (shield on left as one views the print) bears the arms of Pirckheimer - a ‘birke’ or birch tree whilst the sinister (shield on the right as one views the print) bears those of his wife, Margaretha Rieterin – a crowned mermaid with two tails, each of which she holds in her hands. The birch tree is a playful allusion to the jurist’s name. Clasping the helmet are two angels.’ The motto, ‘Sibi et Amicis’ (For themselves and their friends) appears near the top.

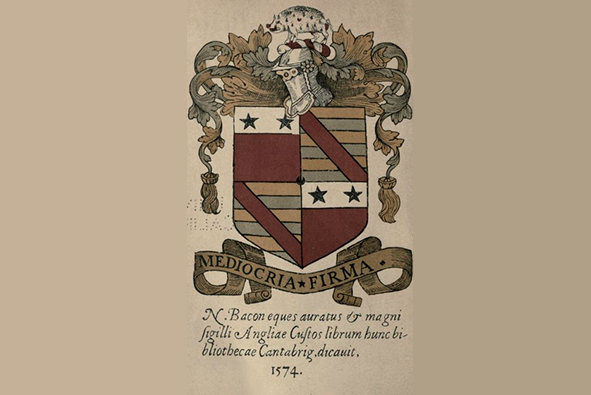

Walter Hamilton in his book ‘French Book-plates’, dates the first French ex libris to 1574, which reads, ‘Ex Bibliotheca Caroli Albosii E. Eduensis. Ex Labore Quies.’ This is the same year as the first English bookplate, that of Sir Nicholas Bacon (father of Francis Bacon). Bacon’s motto ‘Mediocria Firma’ can be translated as ‘The middle way’.

Bookplate of Sir Nicholas Bacon 1574

The first bookplate believed to have been printed in the USA was made with the start of printing in that country. It is a basic typographical label bearing the name Stephen Daye and the date 1642. It has been estimated that there were in excess of three thousand bookplates of early Americans in the century and a half prior to 1830.

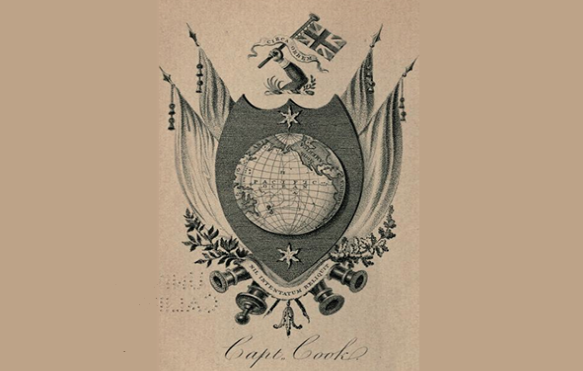

In the Antipodes, the bookplates of Captain Cook and Joseph Banks are often considered to be the first bookplates of Australia, although of course they were not designed or printed there.

Lord De Tabley expresses it well when he says, ‘Some bookplates are interesting because of their heraldry, while some are for their topography, such as W. Williams of Antigua, or the Mexican Convent of St Francis.’ One can add a third reason, namely a bookplate may be interesting for the very reason of its owner.

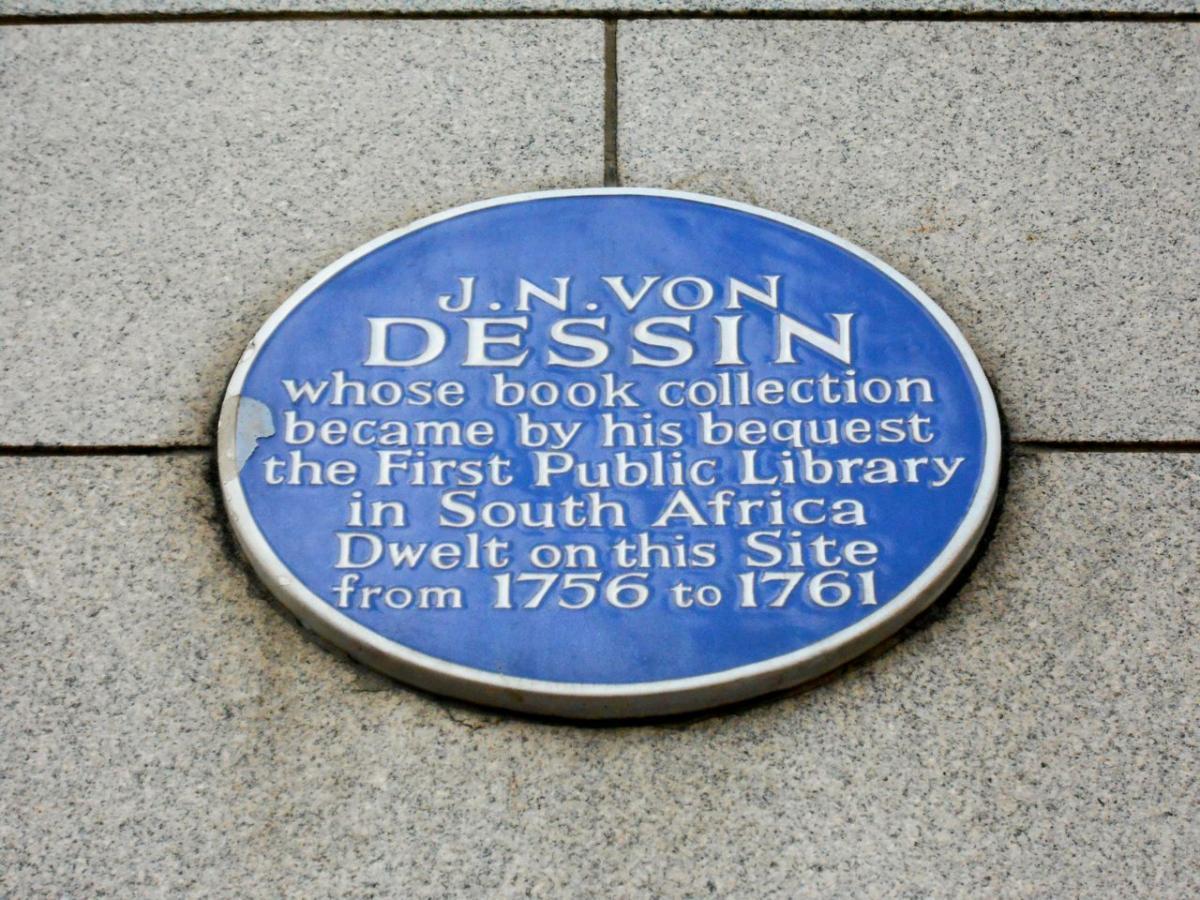

It can be argued that the first South African ex libris is that of Joachim Nikolaus von Dessin (1704 – 1761) an official of the Dutch East Indian Company who wrote his bookplate by hand, ‘Ex libris N. Von Dessin – artem quaevis terra alit’ (every country promotes ability). Von Dessin was South Africa’s first bibliophile who bequeathed his collection of books to the Dutch Reformed Church in Cape Town on the specific condition that the bequest should be the foundation of a public library for the benefit of everyone. His collection totaled about 4 000 books upon his death. Normally a hand written entry would not be considered a book plate, but since printing at the Cape was much delayed because of the reluctance of the Dutch East Indian Company to allow such a dangerous instrument, perhaps an exception should be made in this instance.

Blue plaque commemorating J.N. Von Dessin (The Heritage Portal)

During the last decades there has been a veritable upsurge of publications on bookplates, but only a few books and examples of bookplates will be discussed here.

One of the earliest and most influential books on bookplates is that of J. Leicester Warren (later Lord De Tabley). His ‘A Guide to the Study of Bookplates’ was published in 1880 and reprinted in 1900. Warren was the first to identify the various styles of English bookplate design: Jacobean, Chippendale and Allegorical.

Another informative book is ‘Book-plates’, by W. J. Hardy published in 1893 and reprinted in 1897. It provides much interesting and historical information, not only on English, but also on German, French and American bookplates. It also contains many descriptions of beautiful bookplates of which the Pirckheimer is, but one. The opening verse to this article is a quotation from a chapter in his book on bookplate inscriptions that condemn the stealing of books.

Both of the above two books have long been out of print and are not readily available, but copies may be obtainable from local or more likely, international antiquarian bookshops. Because of the detail provided, they are probably more useful to specialist collectors of bookplates, than to the average reader.

Also, for the more serious collector of bookplates is ‘French Book-plates’, by Walter Hamilton, published in 1892 and reprinted in 1896. It contains some interesting bookplates, such as the one for Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon was well known for devouring books during lulls in battles, speeding from front to front and throwing the volumes out of the windows of his carriage as he finished them, so that he left behind him a trail like that of a paper chase. His books were sumptuously bound but he did not use any bookplate. Nevertheless, Hamilton’s book contains a bookplate designed by L. Joly for his ‘Ex Libris Imaginaires’, which Napoleon might well have used. Hamilton describes this imaginary bookplate as follows, ‘an imperial eagle casting a thunder-bolt, which illuminates the peaks of the Alps; below are seen the emblems of war (remains of cannon etc.), the owl symbolic of wisdom, the Cross of the Légion d’Honneur, and the books of the Code Napoléon.’ It is of great regret to posterity that Napoleon did not have an ex libris designed for his own use.

This book also contains an interesting section on the French Huguenots and bookplates associated with some of these refugees who fled France when the Edict of Nantes was revoked in October 1658. According to Hamilton, the term ‘Huguenot’ seems first to have been applied to Calvinists in about 1560. Some consider the word to be derived from the German ‘Eidgenossen’ signifying a sworn confederacy, whilst others claim it was based on the name of Hugues, a Genevese Calvinist.

‘Australian Book-Plates and Book-Plates of Interest to Australia’ by P. Neville Barnett is an attractive folio edition. The book contains a fair number of bookplates to the Royal Family, as would be expected from an Australian publication of 1950, but there are some bookplates, which may be of some interest to South Africans. One is the bookplate of Captain James Cook (1728 -1779) engraved about 1794, at the request of one of his sons in order to perpetuate the posthumous heraldry granted in 1785 to Cook’s widow. It is an interesting bookplate with a globe of the world displaying the region Cook sailed in the South Pacific, superimposed on a shield, with ship cannon peering out below. The motto ‘Nil Intentatem Reliquit’ near the bottom of the bookplate, appropriately means, ‘Nothing left to Attack’.

Bookplate of Captain James Cook designed posthumously (Wiki Commons)

Another bookplate appearing in this book is that of Sir Joseph Banks (1743 - 1820), the naturalist who sailed with Captain Cook to Tahiti to observe the 1769 Transit of Venus across the Sun. He, along with Captain Cook was amongst the first Europeans to step ashore at Botany Bay, Australia in April 1770. Banks had a strong association with the Cape because their ship, the Endeavour, moored at Cape Town for about a month during the return journey to Britain. Banks became so fascinated by the botany of the Cape, he twice arranged for a botanist to visit the Cape Region to collect plants for the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Joseph Banks was subsequently elected President of the Royal Academy in 1778, which he remained until his death in 1820.

A very suitable book for the layman is ‘Ex Libris – The Art of Bookplates by Martin Hopkinson published in 2011 and reprinted in 2012, by the British Museum. It provides a brief but coherent description of the development of bookplates from the 15th century to the modern day and encloses ninety five examples of interesting and diverse bookplates in the Collection of the British Museum. Some of the bookplates provide useful guidance on symbolism and punning. Hopkinson makes the point that as the audience for bookplates broadened in the late nineteenth century so did the sources for the imagery used in them. Soon artists started including elements of art derived from Japan and the Indian sub-continent. By the end of the nineteenth century bookplates became particularly popular amongst those associated with theosophy, the occult, freemasonry and decadence. From the 1880s and onwards, nudity also became a significant feature in German and Austrian bookplates. During this period the erotic bookplate developed a trend which has remained popular to this day. Interestingly, Hopkinson maintains that bookplate design has remained relatively conservative with almost no examples of the influence of Cubism or Abstraction being found in bookplates.

In South Africa, it regretfully appears that only a handful of articles and/or books on bookplates were published during the last seventy years.

The first publication is a catalogue published by the Africana Museum in September 1950, called ‘Africana Museum: Catalogue of an Exhibition of South African Book-plates.’ This Catalogue was published during or soon after the Africana Museum’s bookplate exhibition of the same year. The author has not seen a copy of this Catalogue, which would now be rare Africana. The Africana Museum’s quarterly publication ‘Africana Notes and News’, dated March 1950, Vol. VII No. 2 states the Museum’s collection of bookplates number well over a hundred different specimens. The article goes on to say that the work of important artists such as Pierneef and W. H. Coetzer is to be found in the Museum collection as well as bookplates of well-known South Africans such as Rhodes, Sidney Mendelsohn and Eugéne Marais. Sidney Mendelsohn is of course the well-known bibliophile who bequeathed his extensive book collection to the SA Library of Parliament and who authored the famous ‘Mendelsohn’s South African Bibliography’, of all books relating to South Africa to the year 1910. Finally, the article also announces an exhibition of the Museum’s bookplate collection would be arranged during the course of 1950.

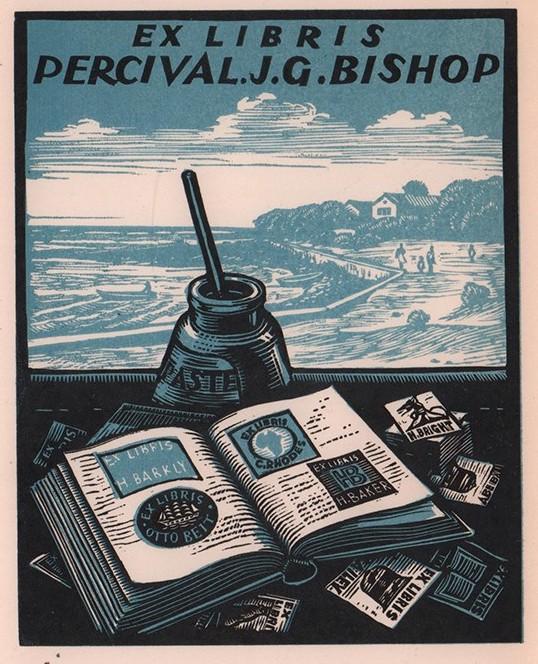

The second is an excellent book ‘South African Bookplates’ by Percival J. G. Bishop, who was an avid and knowledgeable collector of bookplates. His book published in 1955 by A. A. Balkema, contains an informative Foreword by R. F. M. Immelman, University Librarian of UCT and a Preface by F. L. Alexander. Bishop’s bookplate is an attractive wooden engraving in two colours by J. Voigts. The plate displays the view from his seaside home ‘Bishopston’ at Kommetjie, Western Cape, and illustrates his hobbies of bookbinding and collecting bookplates.

Bookplate of Percival J. G. Bishop (Antiquarian Auctions)

This book contains copies of about 70 bookplates with Bishop’s perceptive comments on the merits of most of them. There are bookplates of some important historical figures, amongst others, Cecil John Rhodes, Abe Bailey, Eugéne Marais, Ludovici Peringuey (the entomologist), Florence Phillips, Ernest Oppenheimer, Herbert Baker and Andre Huguenet. Bishop lists in his book the names of approximately 480 South Africans, he is aware of who possess personalised bookplates. One wonders how many South Africans at present have personalized bookplates.

Bishop makes some interesting comments regarding the designing of a bookplate. He says that it is usually the inexperienced amateur and not the artist who forgets a bookplate is more a simple mark than a broadsheet in miniature. He also cautions against overelaboration and reminds us the rule of ‘less is best’ is often applicable. One of the more unusual bookplates in Bishop’s book is that of Sir Rider Haggard, the well-known Victorian author.

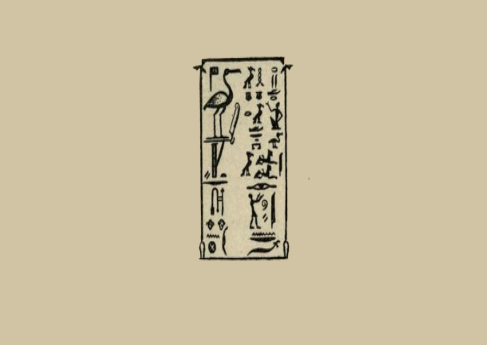

Bookplate of Sir Rider Haggard

Bishop describes the tiny bookplate of Rider Haggard as follows, ‘…. is one of the jocular hieroglyphic plates designed by the Rev. W. J. Loftie, who has also other bookplates to his credit, most of them inspired by ancient printers’ marks.’ Bishop then proceeds to quote British author on bookplates, Egerton Castle, who states, “A hieroglyphic plate might be fitting for the author of ‘She’ and ‘Cleopatra’.” The legend reads: ‘H. Rider Haggard, the son of Ella, lady of the house, makes an oblation to Thot, Lord of Writing, who dwells in the moon.’

Incidentally, in the December 1956 edition of ‘Africana Notes and News’, Vol. 12, No. 4, Bishop states that in his quest for historic South African bookplates, he recently obtained an apparently very rare ex libris of C. J. Rhodes. He explains that this bookplate is not the usual and well-known one which is an armorial shield with a hand holding a sprig of an oak tree, but instead is pictorial showing the landing of Van Riebeeck. It was apparently designed in 1895 by the artist R. Anning Bell.

Bishop’s book remains the premier publication on South African bookplates. It has long been out of print, but copies do occasionally appear at local antiquarian booksellers. Any bibliophile, who wishes to have a bookplate designed for his/her own use, would do well to first peruse Bishop’s book and ponder his advice.

The third is an article by A. Forter entitled, ‘Some notes on the history of bookplates’, published in ‘South African Libraries’ 27 (1)1959. The author has unfortunately not yet seen this article.

The fourth is a chapter on ‘Book-plates of South Africa and South West Africa’, by M. B. Chapman, which appeared in the book ‘Africana Byways’ edited by Anna H. Smith, City Librarian and Director of the Africana Museum. The book was published in 1976 by AD Donker and this chapter provides an informative historical overview and description of the various styles of bookplates. There are also a number of images of bookplates with brief notes to them. Chapman states that Baron Von Ludwig, who died in Cape Town in 1847, may have introduced the bookplate to South Africa. His bookplate is in the armorial style and a copy of it appears in Frank Bradlow’s book, ‘Baron Von Ludwig and the Ludwig’s-Burg Garden’, published by A. A. Balkema in 1965.

Chapman’s chapter is very suitable to the general reader who has some interest in bookplates and copies of this book should be available at local antiquarian bookshops at reasonable prices.

The fifth publication constitutes an article, ‘Some Bookplates in the Brenthurst Library’ by F. G. Brownell, then State Herald, which appeared in Volume I, Number I of the ‘Brenthurst Archives’ of 1994. It presents images and descriptions of some interesting and historical bookplates in the Brenthurst Library, of amongst others, Rudyard Kipling, General Garnet Wolseley, Hans Sauer, Lionel Philips and one for Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, designed by the well-known artist William Timlin. The bookplate of Rudyard Kipling is most attractive, showing a person reclining on a howdah on the back of an elephant, reading a book while smoking from a hookah. Shades of a past comment by Barry Ronge that one only requires a bookshop, a chocolate mousse and a good film to achieve sublime happiness! Kipling’s bookplate was designed in 1894, the year of publication of the first ‘Jungle Book’ and illustrates his love of India and literature. This book is unfortunately also out of print but may be available from local antiquarian bookshops.

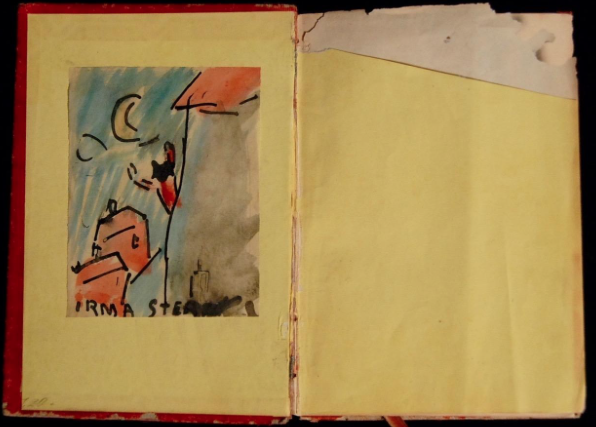

The last publication is a very attractive book written by Dr. Irene Below for The Society of Bibliophiles in Cape Town and published in 2000. The title is ‘Hidden Treasures: Irma Stern - Her Books, Painted Book Covers and Bookplates.’ While this book does not pretend to provide any guidelines to people interested in developing their own personalised bookplates, some of the watercolour bookplates are exquisite and the book will appeal to anyone interested in Irma Stern’s life and art.

Between approximately 1917 and 1925, Irma Stern painted a number of watercolour bookplates, which she pasted inside some of her books. According to Below, Irma Stern seemed to draw the inspiration for a watercolour bookplate not only from the book’s content but also from its style. Below’s book contains examples of 18 watercolour bookplates well as a colour litho plate created for fairy tale books and a linocut plate for literary works.

Unfortunately this book is also out of print but copies do turn up at local antiquarian bookdealers. Incidentally, in 2017 a copy of Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘Bilderbuch ohne Bilder’ (Picture Book without Pictures) containing an original watercolour bookplate by Stern sold through an antiquarian book auction for $1700, which seems to be a reasonable price for an original, though admittedly minor work of art by Stern.

Watercolour bookplate by Irma Stern of a lonely artist having relocated to a new city, greeting with relief the familiar face of the moon. (via Quagga Books)

Lastly, the author can do no better than to conclude with the words of Percival J. G. Bishop, ‘If you have experienced the joy of meeting with a fine ex libris, when opening an ancient volume – a gleaming plate, which is a little memorial to the exquisite or quaint taste of bygone times, then you owe it to the coming generations to leave them in your volumes too, a valid token of your own pleasure in book collecting and of our own times as well.’

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South Africa's history.

Bibliography

- Africana Notes and News. December 1956 Vol. 12, No. 4. Africana Society, Africana Museum. Johannesburg

- Barnett P. Neville. 1950. Australian Book-Plates and book-plates of interest to Australia. Privately printed. Sydney, N.S.W. Australia.

- Below I. 2000. Hidden Treasures: Irma Stern – Her Books, Painted Book Covers and Bookplates. The Society of Bibliophiles in Cape Town.

- Bishop P. J. G. 1955. South African Bookplates from the Percival J. G. Bishop Collection. A. A. Balkema. Amsterdam, Cape Town.

- Bradlow F. 1965. Baron Von Ludwig and the Ludwig’s-Burg Garden: A chronicle of the Cape from 1806 to 1848. A. A. Balkema. Cape Town.

- Brownell F. G. 1994. Some Bookplates in the Brenthurst Library in Brenthurst Archives: Footnotes to History from The Brenthurst Library, Johannesburg, the Private Africana Collection of Mr. H. F. Oppenheimer. Volume I Number I 1994. The Brenthurst Press, Johannesburg.

- Goodman P. 1956. American Jewish Bookplates. American Jewish Historical Society. New York.

- Hamilton W. 1896. French Book-Plates. George Bell, London.

- Hardy W. J. 1897. Book-Plates. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. Ltd. London.

- Hopkinson M. 2012. Ex Libris - The Art of Bookplates. The British Museum Press. Toppan Leefung Printing Ltd., China.

- Smith A. H. Editor. 1976. Africana Byways. AD. Donker, Johannesburg.

- Suid–Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Vol. I. 1976. Tafelberg Uitgewersbeperk, Kaapstad.

- Warren J. L. 1880. A Guide to the Study of Book-Plates (Ex Libris). John Pearson, London.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.