Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, journalist Lucille Davie explores the painful history behind the Worker's Library and Museum in Newtown. The piece was originally published on the City of Joburg's website on 10 October 2008. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

The Newtown Workers' Electricity Compound, the last remaining example of a workers' compound, exposes the brutal underbelly of living conditions for black workmen in apartheid Johannesburg. It is to be opened in 2009 as a museum commemorating the municipal workers of the city.

Men used to sleep in long rows of hard concrete "beds", next to one another, a small concrete lip separating one from the next, with no privacy. A wooden platform above the concrete beds accommodated more men. Each dormitory contained a coal stove, used for heating and cooking, while dishes and probably clothes were washed in a long slanted concrete basin directly outside the dorms. Bathrooms with open showers were at the eastern side of the building.

Long rows of hard concrete "beds" (Lucille Davie)

Built in 1913 and referred to nowadays as the Workers' Library and Museum, the Newtown Workers' Electricity Compound consists of three semi-detached "shiftmen's" or artisans' cottages, and a stand-alone manager's house. Directly behind them are several corrugated iron shacks, housing domestic workers who worked for the artisans and manager.

And behind the shacks lies the U-shaped workmen's quarters, a red-brick, single-storey building with a wraparound veranda and a courtyard, reminiscent of a British-style primary school with a quadrangle.

Newtown Workers' Electricity Compound from above (google maps)

Workmen's quarters (The Heritage Portal)

"The Newtown compound is the only intact example of an early municipal compound in Johannesburg," explain architects Henry Paine and Barry Gould, and historian Sue Krige in a report on the complex. The compound was in use until 1976.

The workmen's quarters housed about 396 men who worked on the city's electricity generating plant right on their doorstep.

"The electrical precinct as a whole tells the story of the extraordinary expansion of Johannesburg, a global city, and central to this growth, the role played by the provision of power," say the researchers.

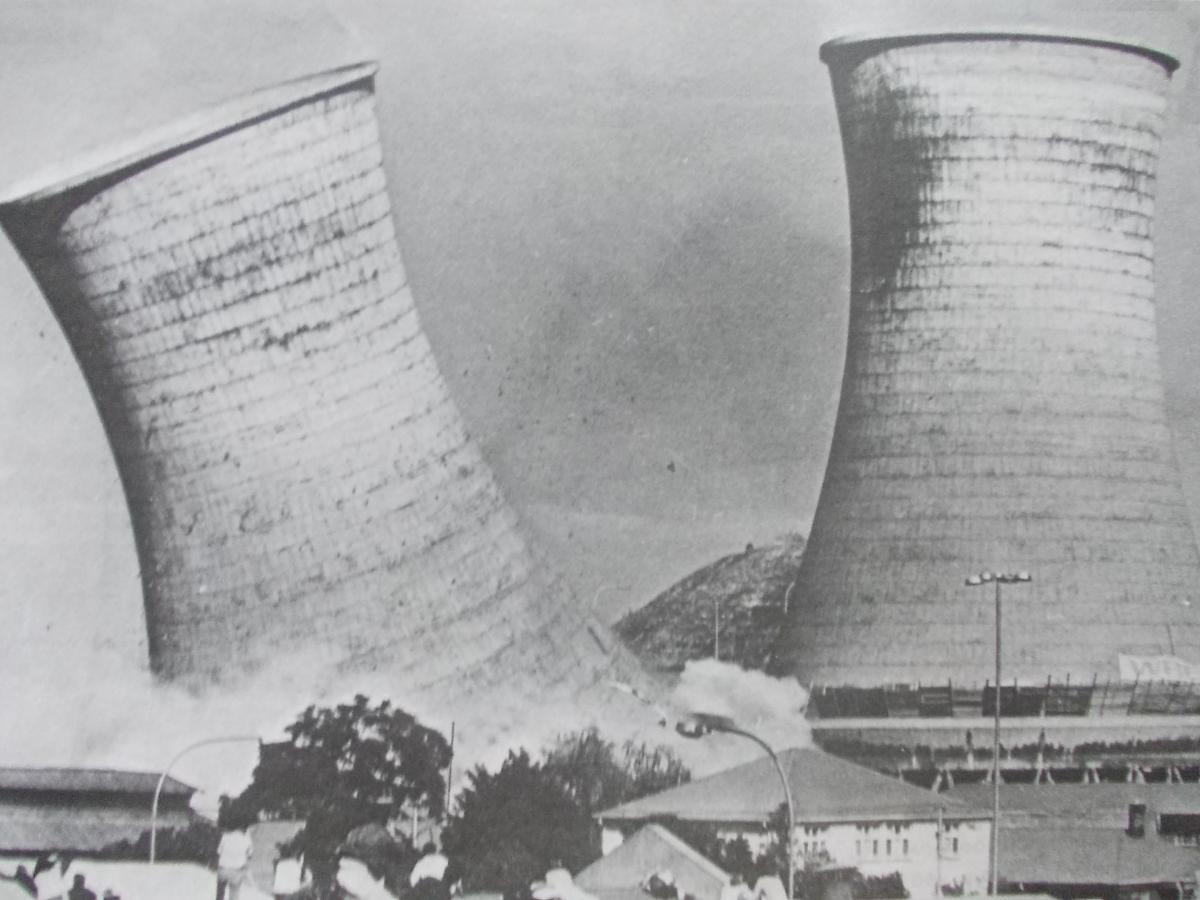

Demolition of cooling towers

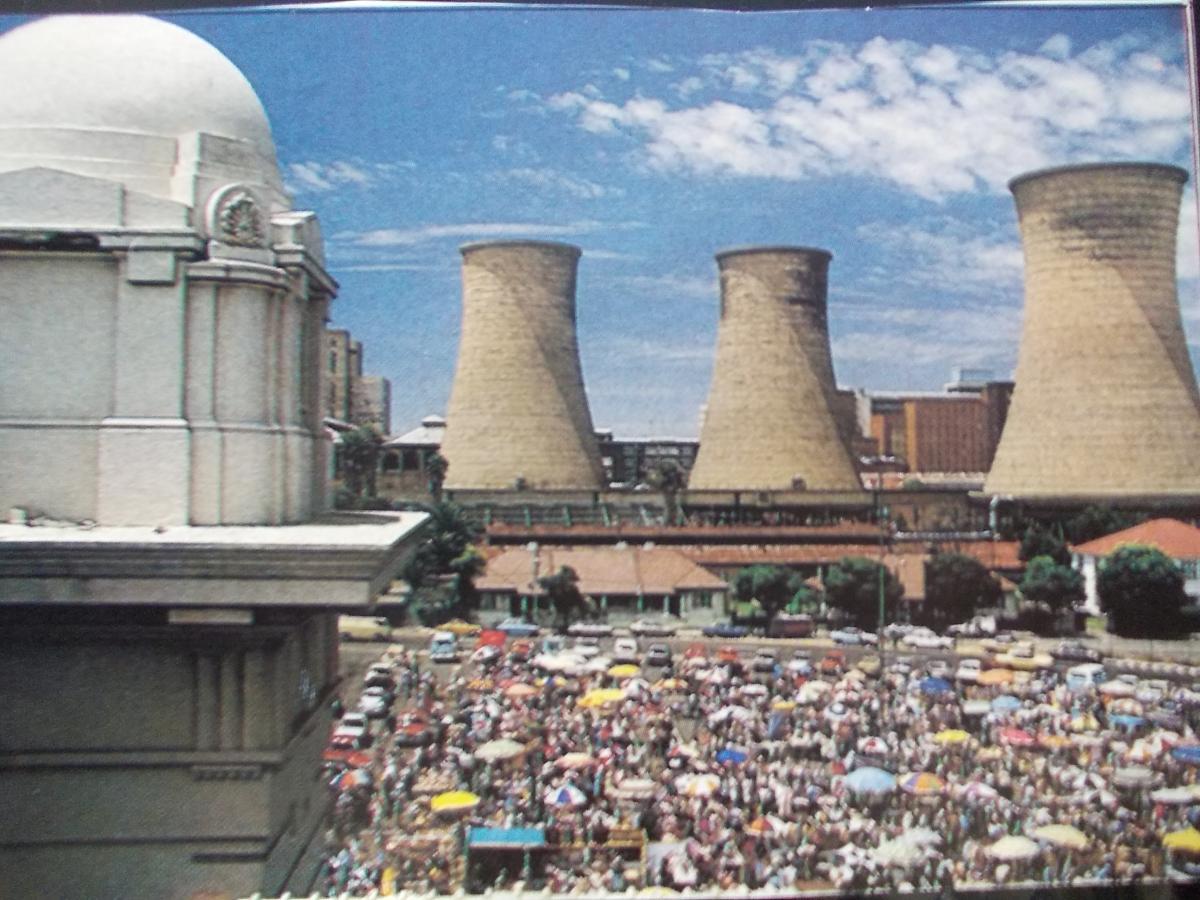

Joburgers may remember the four giant cooling towers, positioned between the workers' quarters and the Electric Workshop, now the Sci-Bono Centre, that were imploded two at a time in 1985. Their implosion changed the face of Newtown dramatically, but opened up space, now a green field used for concerts and other gatherings.

Demolition of the Cooling Towers

The Cooling Towers on Market Day

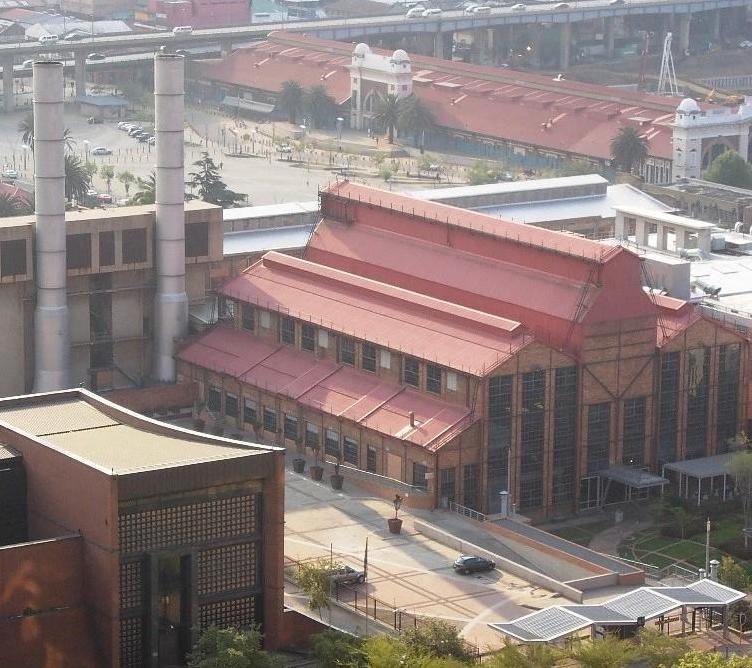

Other buildings in the electricity complex include the Turbine Hall, now converted to offices for AngloGold Ashanti; and other assorted buildings and chimneys in that block, long gone except for one solitary chimney.

Turbine Hall (The Heritage Portal)

Turbine Hall from above (The Heritage Portal)

Two blocks of Miriam Makeba Street, on the eastern border of the complex, did not exist originally, the space for the road only having been created since the demolition of the buildings.

A short avenue of large, mature palm trees runs east of the compound, offsetting the old buildings, a reminder of the age of the site.

Electricity was produced from this Newtown plant until 1976, when Eskom put pressure on the City to close it and the Orlando Power Station in Soweto. After that time the council used the building largely as a storage facility, removing the doors and most of the concrete beds.

The report indicates that when the electrical compound in Newtown was built, there were already 12 compounds in the city, most of which were for cleaning department workers. Others were built for the engineering, gas, and tramways departments. They were built in Vrededorp, Bertrams, Bez Valley, Jeppestown, Troyeville, Wolhuter, Norwood and Natalspruit.

Workers were migrants, and the compounds were a model of the gold-mining industry's compounds. "The Johannesburg municipality was the second largest employer of migrant workers, outside the mines," says the report.

The mine compound model was first introduced by De Beers in Kimberley in the 1870s, to house diamond workers.

Original library

The original Workmen's Library contained some 6 000 volumes and 2 500 articles and pamphlets, opened in 1988 in De Villiers Street, opposite Khotso House, where the South African Council of Churches offices were located before they were bombed by the apartheid government. Donations were received from labour activists and unionists.

The library then moved to Troye Street, where weekly seminars and workshops were held, says Anne-Katrine Bicher, the project manager of the Workers' Museum Re-development Programme at Khanya College in the CBD, where the library is presently located.

High rent in Troye Street forced it to look elsewhere, and the old Newtown compound was identified as a possible site. The Workers' Library and Museum opened in Newtown in 1995.

"At its new location the library was not only a place for reading and studying, but also a venue for book launches, political discussions and educational and cultural events, highly popular with a large number of people who otherwise wouldn't have had access to books, information and a venue for cultural activities," says Bicher.

In the same year a concrete statue of a worker in orange overalls and holding a spade, was placed on a metal pedestal in front of the building. The commission was overseen by artist Andrew Lindsay, using artists from Tembisa. It was commissioned by the Municipal Workers' Union and stands several metres tall.

In the late 1990s the library formed a partnership with Khanya College, which also took up residence in the Newtown building. Both organisations moved to Vogas House in Pritchard Street in 2006. The Workers' Library Resource Centre opened in this new location in 2007.

"Khanya College's decision to move from the historic workers' compound to a newer, larger building in the nearby Johannesburg CBD, offered the opportunity to overhaul and reopen the resource centre with renewed enthusiasm," adds Bicher.

She says the museum consisted largely of artefacts from the municipal workers, like cooking pots and plates, and wooden boxes in which they stored their belongings.

Research is ongoing to find more artefacts, and some 30 interviews have been conducted with former residents of the hostel. Bicher says all municipal hostels in the province are being researched.

Historian Lauren Segal is working on the displays for the new museum. The two rooms that remain as they were when the workers lived in them are to be recreated, largely from photographs. Items like sewing machines, suitcases, bicycles and cooking equipment are being collected for the displays. Segal says some of the workers had weekend tailor businesses.

Front of the Worker's Museum (The Heritage Portal)

National monument

In 1995, the buildings were declared a national monument, and in that year conservation architect Henry Paine restored the complex, replacing the missing doors with new ones based on the originals, in addition to replacing some of the windows and all the rusty gutters.

This year Paine again restored the library - giving the walls a new paint job, placing steel beams to hold up sagging interior trusses, and replacing the neglected gutters.

The Johannesburg Development Agency's Celestine Mouton says this is phase one of the restoration, costing R1,6-million. A visitors' centre, directly in front of the courtyard, will be built as part of phase two, when more funding is available. The cottages fronting Mary Fitzgerald Square will also, in time, be restored.

The centre will be flat-roofed so as not to interfere with the sightlines from the compound. A fence, encasing the southern, eastern and western edges of the compound, will be erected to protect the building from further degradation, as has happened over the past dozen years.

"Industrial heritage should have cultural value and significance, particularly for a city like Johannesburg," says the report. "It can be argued that there has been a consistent undervaluing of Johannesburg's industrial architecture and heritage, to the point of malicious neglect."

The wilful demolition of the Richmond laundries is certainly testimony to this. The site, called the Rand Steam Laundries and Cleaning and Dyeing Works, was established in 1902 and consisted of a small village with cottages for workers and managers; a blacksmith; a farrier for making and maintaining its carts, which were used for collecting and delivering laundry; and a soap-making section.

Now it stands as an almost empty plot, with weeds growing where once a distinctive collection of buildings told of Joburg's early laundry industry. (Click here for updates on the Rand Steam Laundries Site)

Rand Steam Laundries Site in 2017 (The Heritage Portal)

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.