Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Forty years ago at the 48th Academy Awards (1976) O.J. Simpson opened the envelope and announced that “GREAT” had won the Oscar for the Best Animated Short Film. The recipient was Bob Godfrey the film’s maker.

The movie “GREAT” is a classic of animation and in a mere 30 minutes tells the story of the most famous of all the Victorian engineers - Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Alas the film has been out of circulation for sometime and is briskly taken off “You Tube” whenever it is uploaded. I remember watching it at the Drive-In in 1977, as a “Short” and although I have forgotten what the Main Feature was, I still remember well watching “GREAT”.

Documentary Poster

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) is very much revered in Britain and the reverence borders on cult worship. The title of the book “BRUNEL - The Man Who Built the World” (by Steven Brindle, published in 2005) shows the measure of the esteem accorded to him.

On the 2002 BBC television series “GREAT BRITONS - The great debate”, the Top Ten Britons were chosen (as whittled down from 100). In the first episode Jeremy Clarkson (late of “Top Gear”) gave a compelling argument as to why Brunel should be the Greatest Briton of all time, saying that he was “The most prolific and talented engineer and innovator of them all”. When the votes of a poll (more a popularity contest) were counted Winston Churchill was out in front as the Greatest Briton (28.1%), followed closely in second by I.K. Brunel (24. 6%), with Princess Diana third (13.9%), ahead of such notables (in descending order) as Darwin, Shakespeare, Newton, Elizabeth 1, John Lennon, Lord Nelson and Cromwell. Whether Churchill and Brunel were in fact the greatest Britons matters not, what matters more is their place in the national consciousness of Britain - the country which invented the modern world we live in.

Clarkson filming in the Thames Tunnel

When I.K. Brunel was born on 9th April 1806, it was into a world powered by the horse and by the elements of wind (sail and mill) and water (wheel), yes the steam engine had been invented but it was yet to become the main driver of British industry in the Victorian Era (1837-1900). Isambard’s father, Marc, was a Frenchman forced to flee the Revolution and after a spell of living in America he came to England to marry Sophia Kingdom (they had first met in France in 1793). An engineer and inventor by profession he first sought work from the Admiralty and would live the rest of his days in England.

Marc Brunel’s “Opus Magnum” was the Thames Tunnel, between Wapping and Rotherhithe (downstream of London Bridge); the first tunnel ever to be built under a body of water. The young Isambard worked as his father’s resident engineer on the tunnel and nearly lost his life when water rushed into the workings. Work on the tunnel started in November 1825 and it was estimated to take 3 years to complete but in fact took far longer and was only opened to the public on the 25th March 1843 (17½ years later), this was due to work being stopped on several occasions as a result of cave-ins. The Tunnel was considered the most hazardous civil engineering project to be undertaken during the first half of the nineteenth century. In fact at one stage Isambard thought that the tunnel would be abandoned as had been the case with the two previous attempts of 1801 and 1807; he wrote in 1831 “Tunnel is now, I think, dead. The Commissioners have refused on the ground of want of security. This is the first time I have felt able to cry at least for these ten years. Some further attempts may be made - but – it will never be finished in my father’s lifetime I fear. However nil desperandum has always been my motto – we may succeed yet. Perseverantia”.

Marc Brunel did live to see his Tunnel opened and for a while it became a major tourist attraction - the Eighth Wonder, but because there were no approach roads, carriages could not pass through it and it remained for pedestrians only, thus limiting its potential as a major river crossing. Eventually it was bought by the East London Railway and was converted for railway use and is still utilised today by the London “OvergrounD” services (orange on the London tube map).

Isambard, after his near death experience in the Tunnel in 1829, was sent to Clifton on the outskirts of Bristol to convalesce, where he not only regained his health but was also able to enter a competition in 1831 for the design of a bridge to span across the Avon Gorge - the Clifton Suspension Bridge (main image and below). The bridge competition was judged by Thomas Telford (the pre-eminent civil engineer of the time) and he found favour with none of the twenty or so entries and therefore put forward his own proposal, which was a monstrosity, out of keeping with the beauty of the gorge. Luckily the bridge committee, under the pressure of public opinion, called for a second competition and co-opted Davies Gilbert to be the judge. Of the twelve entries five were deemed to be worthy of further examination. The five on the short list were by Telford, Brunel, Rendel, Hawks and Captain Brown, but there could only be one winner and after much deliberation and discussion with each contestant, Brunel came out on top. The bridge would have many delays during its construction period (owing to lack of finance) and would not be completed until 1864, 5 years after Brunel’s death and the bridge that he had called “my first child, my darling” would become his Memorial.

The Clifton Bridge would become his memorial

The success of winning the bridge competition launched him on his own career path, distinct from his father’s and more commissions came his way courtesy of the Bristol Dock Company.

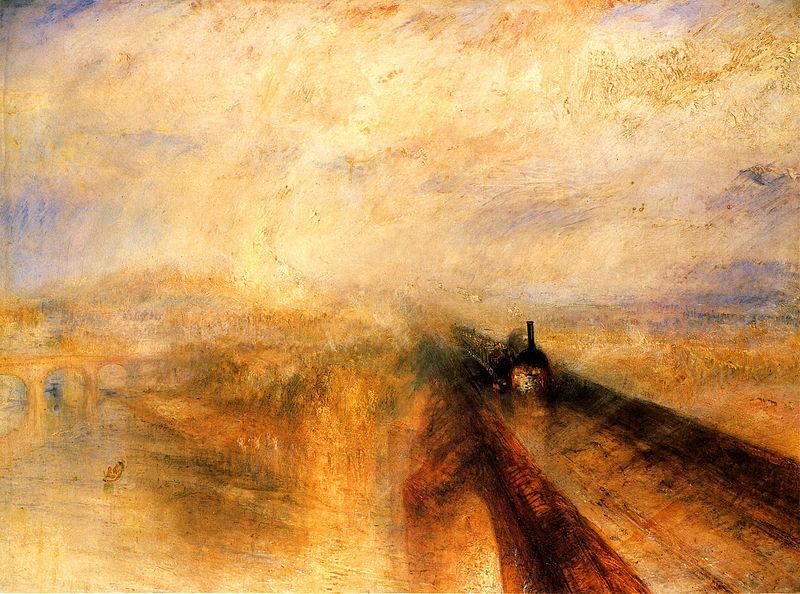

Bristol considered itself second only to London as a port and with the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830 and plans laid by the Stephensons for railways linking London to the North West, saw Liverpool as a threat to its future trade. The businessmen of Bristol pictured a scheme of a railway between their city and the capital, to be known as the Bristol and London Railway and chose the younger Brunel to be their Chief Engineer in 1833; when he was but 27 years old. The railway would soon change its name to the more grandiose Great Western Railway (GWR) and Isambard’s name would be forever synonymous with the GWR. The line was to be known as Brunel’s billiard table as it was designed to be a high speed line, which necessitated it to be as straight and level as possible. The two most notable civil works on the line were to be the bridge over the River Thames at Maidenhead (the subject of Turner’s painting “Rain, Steam and Speed”) and the tunnel, 3 000 yards long, under the hill at Box, east of Bath.

Rain Steam and Speed the Great Western Railway (Wiki Commons)

His vision knew no bounds and he went on to extend the railway system into the West Country and Cornwall on his own Broad Gauge of 7’- 0 ¼“ (2 140mm), George Stephenson’s coal wagon gauge of 4’-8 ½“ (1 435mm) was not for him.

The United States of America had gained their independence from Great Britain in 1783, however this did not mean severing all ties with the “Old Country” and there was a free flow of people, knowledge and trade between the “New World” and the “Old”. Bristol’s links with North America stretched back to the days of the Italian born John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto), when he set sail from Bristol in May 1497, in search of the North West Passage to Asia. He was the first since the Vikings to sight the shores of North America and claimed “New-found-land” for the King of England - Henry VII. Subsequently the British and the French established colonies in North America and the Caribbean, which brought about the Triangular Trade on which Bristol’s fortune, was made.

Isambard whilst planning and surveying the GWR was thinking ahead and asked the question “Why not make it longer and have a steam boat to go from Bristol to New York, and call it the Great Western”. In the quotation “it” refers to the GWR and Brunel’s proposal was to have a combined rail and sea transportation route from London to New York. This idea set him on a new course of endeavour - naval architecture and he subsequently built with his associates the steam ships, the Great Western, the Great Britain and the Great Eastern.

To say that Isambard was a workaholic would not be an exaggeration as he was known to work twenty hours a day when the need arose and with his high workload and the stress incurred with the floating of the Great Eastern and the subsequent sea trials, it was little wonder that his health failed. He died of a stroke, at the age of 53 years, shortly after seeing his railway bridge over the Tamar opened, connecting Devon with Cornwall. His contemporary, rival and friend Robert Stephenson would die in the same year, aged 56 of the same cause - overwork. The third member of the railway building triumvirate, Joseph Locke died a year later at the age of 55.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s vision, energy, persistence, commitment to quality and his ability to inspire others are all important lessons for us today. Even when he faced a failure; the atmospheric railway in South Devon was a case in point, he was able to accept the failure cut his losses and appease his shareholders, such was his character. Who in our day and age has those Brunelian qualities? One man that I can think of is the South African emigrant Elon Musk, who is pushing the boundaries of technology, with his Tesla Motors and SpaceX companies.

Returning to the movie cartoon “Great”, it was Bob Godfrey’s cheeky tribute to Brunel and is a musical romp through the life, works, achievements and yes, failures of the great man and it is about time that it was re-issued as a DVD as it would not only be great entertainment but also highly informative. The song that goes “Get a big top hat if you want to get ahead, it doesn’t really matter if you’re not at all well bred” still plays in my head.

I hope that what I have written above will whet your appetite to find out more about Brunel and indeed his contemporaries who shaped the world as we now know it.

Peter Ball's son James enjoying a visit to the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 2005

References and Further Reading

- “GREAT BRITONS - The Great Debate” by John Cooper a companion book to the BBC TV Series 2002.

- “BRUNEL The Man Who Built the World” by Steven Brindle.

- “Isambard Kingdom Brunel” by L.T.C. (Tom) Rolt.

- “Isambard Kingdom Brunel” by Robin Jones.

- “Brunel’s Kingdom” by John Chrisopher.

- “Brunel’s Britain” by Derrick Beckett

- “Down the Line to Bristol” by Muriel V. Searle

- “Men of Iron - Brunel, Stephenson and the inventions that shaped the modern world” by Sally Dugan

- “Brunel, GWR and Bristol” Michael Harris editor.

- “The Brunel Effect - the lessons that Isambard Kingdom Brunel offers today” by Andrew Kelly.

- “The Industrial Revolutionaries – the making of the modern world, 1776-1914” by Gavin Weightman.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.