Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, well-known journalist Lucille Davie explores the rich social history of the Bantu Men's Social Centre and Dorkay House in downtown Johannesburg. Both buildings have received blue plaques since her article was first published on the City of Joburg's website on 2 November 2006. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

The Bantu Men’s Social Centre and Dorkay House, significant symbols of black artists’ resistance to apartheid during the 1950s and ‘60s, survive still at the southern end of Eloff Street, one in good condition, the other rundown but still in use.

Queeneth Ndaba has been associated with Dorkay House for decades. I had phoned her to ask about the two places and after we chatted for a while, she invited me to come and visit her. She told me to meet her at Madiba Village, opposite the Bantu Men’s Social Centre.

The small rehearsal room in Dorkay House on the first floor has seen many aspiring dancers, singers and actors fill its tiny stage while the large hall in the neighbouring centre has hosted many memorable evenings.

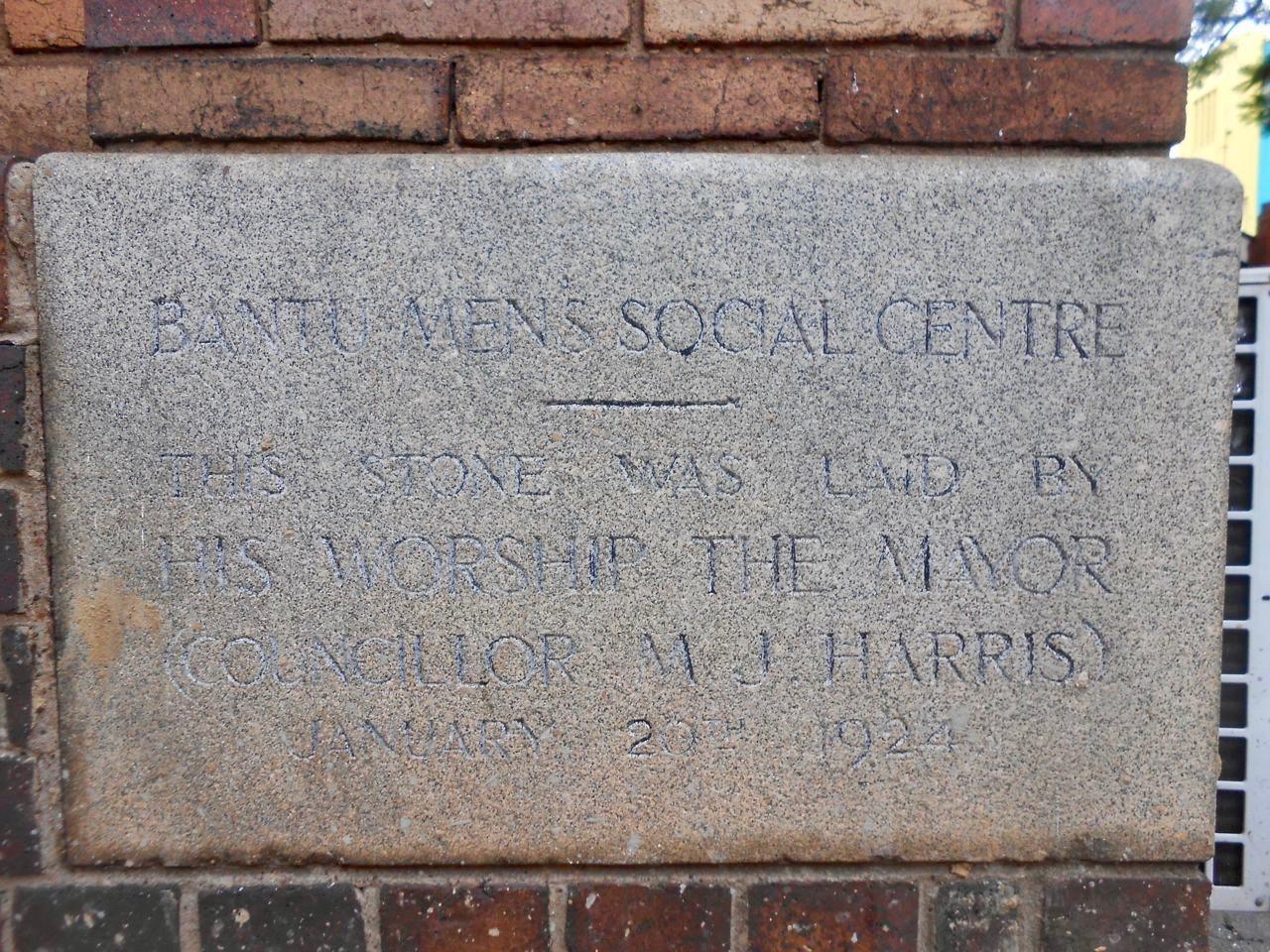

A foundation stone at the centre indicates that it was opened in January 1924. Its aim was to provide recreational activities for young black men and those activities included “sporting events, debates, writers’ conferences in the 1930s, musical sessions and plays, under the auspices of the Bantu Dramatic Society”, according to Naomi and Reuben Musiker in A concise historical dictionary of greater Johannesburg. There was also a tennis court alongside the building.

Foundation Stone (The Heritage Portal)

It was patronised by members of the “aspirant black middle class, including writers, teachers and journalists”. Athol Fugard’s No Good Friday premiered at the centre in 1958. The following year his Nongogo was performed there, according to wikipedia.org.

The centre offered training in jazz and classical music in the 1950s, with one room containing a number of gramaphones which gave members a taste of music they might not have had access to otherwise.

One of the founders of the centre, Herbert Isaac Ezra Dhlomo, established a branch of the Carnegie Library at the centre, writes Musiker.

The centre has seen significant history taking place in its large hall. It was in this building that the African National Congress Youth League was launched in February 1944. The first members were Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Anton Lembede and Oliver Tambo. Sisulu was elected president, and after his marriage to Albertina in the former Transkei that year, his wedding reception was held at the centre.

The Large Hall inside the Bantu Men's Social Centre (The Heritage Portal)

Twelve years later, in 1956, a farewell concert was held at the centre for Father Trevor Huddleston, Sophiatown’s beloved priest, who was being recalled to England by his superiors. They feared his anti-apartheid activities would land him in jail.

But membership declined, probably as the Group Areas Act started to bite, and in 1971 the centre closed its doors, says wikipedia.org. The West Rand Administration Board moved into the building in 1973. Now the Johannesburg Metro Police occupy the building, just one of a large complex of buildings that house their headquarters.

Bantu Men's Social Centre (The Heritage Portal)

Another shot of the Centre (The Heritage Portal)

Dorkay House

Originally a clothing factory and reborn as a cultural centre for blacks in the 1960s, Dorkay House is fondly remembered by many people.

Musician Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse remembers going there for drumming lessons as a youngster, arranged by the African Music Drummers’ Association. There he met some of the old greats. “They inspired us to choose our careers,” he says.

Dorkay House was the incubator of many talented South African musicians: Miriam Makeba, Jonas Gwangwa, Kippie Moeketsi, Ntemi Piliso, the 10-member African Jazz Pioneers, Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim and actor John Kani.

It is remembered as the place where the hugely successful King Kong was created.

The four storeys of a somewhat rundown Dorkay House are now used for residential accommodation. The ground floor is rented to retailers.

The building is owned by the Kotzen family, managed by third generation cousins David and Clive Kotzen. David says it was built by his grandparents in the late 1940s or early 1950s.

He says he had an unsolicited offer of around R1-million, but he didn’t pursue it because the building would have lost its identity by being turned into a residential block, the purpose of the proposed purchase. “I have spoken to others who are interested in restoring the building to its former glory,” he says, “it’s a pity it is not used [as a cultural centre] anymore.”

Kotzen says he is maintaining the building, at times at his cost, but he gets very little income from the tenants.

He’d like to see a museum created in the building, recording the rich history of the personalities and their times in Dorkay House. Because the building has been in the family for so long, he feels there is a “civic responsibility” to hold on to the building until it can be restored and recognised as a place that played a significant role in black cultural history.

Former singer Ndaba remembers working in Dorkay House from around 1967, when she used to design and make costumes for the shows, like the original Ipi Thombi.

Ndaba started out at a singer. She says her parents used to sing, and she had a group called the Hometown Kids. She grew up in Orlando East and went to Orlando High School. But then she discovered she had throat cancer, and had to give up singing.

Her voice croaks still as I sit opposite her in the small reception room in her office across the road from Dorkay House, in Madiba Village, a large nondescript building on the corner of Eloff Street and Wemmer Jubilee Road.

It was quite a mission to get to her office, and impossible for her to explain the route. So she said she’d meet me out on the pavement. I didn’t find her but after asking at the shop on the corner, I was told to go to Indaba Chicken & Jazz Shop, a couple of shops down the road, and luckily bumped into Nomaswazi Madonsela, Ndaba’s assistant.

Queeneth Ndaba (Lucille Davie)

Dorkay House Trust

Madonsela takes me around the back of the building, up a long ramp, into the dark entrance of the first floor. Then up another flight of stairs, she unlocks a sturdy steel gate, and we enter the slightly musty rooms of the Dorkay House Trust, formed to revive Dorkay House, and nowadays, an events management organisation, run by Ndaba. She says it used to be the OK Bazaars building.

Madonsela offers me tea and invites me to wait for Ndaba. Five minutes later a slim woman who looks around 55, walks in. She is Patricia Moetaphele. She’s 71, and has a sparkle in her smile. She has come to say hello before she goes across the road to rehearse at Dorkay House.

She used to be a chorus dancer and singer, and from the look of her, if you offered her a place in a chorus line now, she’d jump at it. She says she sang with Sophie Mgcina and Margaret Sangana. She used to do ballroom dancing at the Bantu Men’s Social Centre, she says. “I fell in love with dancing. The teachers treated us like babies.”

She started working as a domestic worker at the age of 14, and whatever money she had went to pay for dance classes. “I would jive the whole night with [jazz musician] Zakes Nkosi,” she says, a big smile flashing. “I can teach anyone to dance, sweetheart.”

She was born in Sophiatown and remembers being forcefully removed from the suburb in the 1950s, when she witnessed her father’s house being demolished.

Moetaphele used to choreograph, she says. “I can still choreograph because I am still alive – all the knowledge is here,” she says, pointing to her head.

Ndaba walks into the room. Looking tired, she takes a seat and calls for a cup of tea. She turns 70 this month, she says, but remembers all the old-time singers. Her long-cherished wish was to bring the “big five” together in a concert: Dolly Rathebe, Sophie Mgcina, Dorothy Masuku, Abigail Khubeka, and Thandi Claasens.

Of Mgcina she says: “She was the best, the best.” And of Rathebe: “When Dolly sings gangsters put their guns down.”

The first two recently passed away, but Ndaba feels that the other legends can pass on valuable skills to young hopefuls. She has revived other groups – the African Jazz Pioneers and the Junior Manhattan Brothers.

”I would like to keep the legacy of those who influenced our legends.” She would also like to do a tribute to Ella Fitzgerald, whom she feels influenced a lot of local singers. “This is my wish, it might be a dream,” she says wistfully.

She has had that dream for many years. Back in 1993 she arranged a concert at the Civic Theatre to raise funds to restore Dorkay House, bringing together her big five.

She still has this dream. Several weeks ago she met Pallo Jordan, national minister of arts and culture. “He is considering it – he is positive about the idea,” she says.

She would like to see music classes being held there again. “I have four pianos, guitars, a piano accordian.” Masuku, Khubeka and Klaasens still use the rehearsal room.

Rehearsal room

Moetaphele invites me to walk across the road with her to Dorkay House, where she’ll show me the rehearsal room. We cross the busy road arm in arm, and after negotiating with the caretaker to bring the key, we walk up the stairs to the first floor. The walls of the staircase are decorated in a mural, depicting cheerful singing characters, mouths open in large, round shapes; others playing the saxophone and the electric guitar, surrounded by happy dancers. A glimpse of a vibrant past at Dorkay House.

The Staircase at Dorkay House (Lucille Davie)

The rehearsal room door is unlocked and we walk in. It’s a room of about 15m by 8m, with shiny, red linoleum floors, and dusty pink walls. Three people drift in, taking their places on the small, elevated stage. One sits at the piano, another pulls up a double bass, and a third looks around for the drumsticks while sitting down at the drums.

Soon a beat is coming from the musicians, their heads start nodding, feet tapping. Moetaphele smiles, steps up on the stage, and starts moving her body. Her skirt sways to the sounds, her hips move rhythmically, her head tilts backwards a little, her eyes close. She is transported to another time. She opens her eyes, looks at me, and smiles.

I remember something she said to me earlier: “I’m refusing to die.”

Perhaps Dorkay House also refuses to die.

Practising at Dorkay House (Lucille Davie)

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.