Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

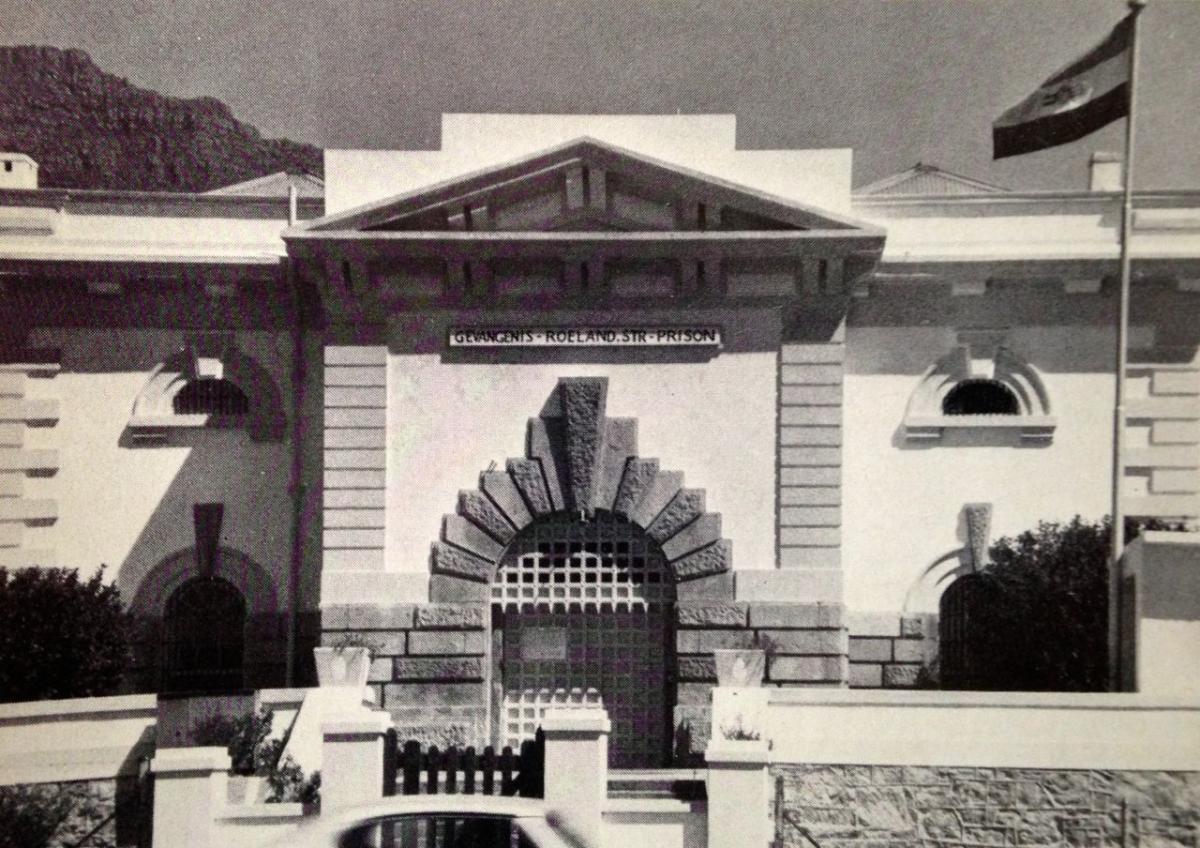

The fascinating article below appeared in the first ever edition of Restorica, the journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (today the Heritage Association of South Africa). It looks at the building of the Roeland Street Prison and its transformation from 'palace' to rat infested institution. The prison was demolished a few decades ago to make way for what is known today as the Western Cape Archives and Records Service. Part of the outer wall and the old main entrance to the prison have been preserved. Thank you to the University of Pretoria (Restorica copyright holders) for giving us permission to publish.

Roeland Street Prison - once labelled Cape Town’s own Black Hole - was originally meant to be an example of good taste to the inhabitants of this city. Now, this 111-year old landmark is to be closed down and replaced with a modern institution at Pollsmoor. It is time to reflect that when Colonial Engineer George Pilkington set about building the prison in 1855 his grandiose plans were almost scuppered by two factors which still plague city engineers today - a shortage of cash and labour. Tenders for the jail came to £20 000. But the House of Assembly would only vote £15 000.

Grey’s Letter

A letter to Governor George Grey in Pilkington’s spidery copperplate then informed that he was able to complete the prison for that sum, but only if most of the ornamental work was deleted and the prison rose little higher than the portcullis.

He also intended dispensing with granite foundations except for 16 cells which would be used for the most vicious offenders. There would be no furniture in the church or in the cells, no boilers or stoves in the kitchen. Missing, too, would be one wing of the projected prison and any stone or ornamental work.

But back came a letter from the Colonial Secretary. In effect it said: ‘Hold it!” No bunks and cold food for prisoners were all right with the Governor, the letter inferred, but the secretary noted that Sir George ‘is unwilling to dispense (with the ornamental work) as he deems it inexpedient to deprive the exterior of the building of all architectural beauty believing, as he does, that the display of correctness and taste of design in the public buildings of a town have an influence, by no means to be neglected, on the taste of the inhabitants and encourages improvements in the erections of private edifices.’ Phew.

The secretary added that the Governor would ask Parliament for another £550 so the ornamental work could be done and warned that the building was not to go beyond a point at which the ornamental work could be added.

Shortage then

Meantime, Pilkington was doing his best to cut down on labour costs. But it was tough. There was a shortage of skilled craftsmen in the colony and ordinary labourers could earn up to three shillings a day, whereas the engineer’s budget for the job could only afford one shilling.

While his 120-man labour force sweated away at the job, the Governor in 1856 asked Parliament if he could have the extra £550 for ornamental work.

This researcher could find no record that the House of Assembly actually voted the funds, but a clerically proud letter from Pilkington in 1858 informed the Governor that he had managed to stick to most of the original design, plus build the steps and the ornamental work for less than £15 000.

How? According to Pilkington it was done by ‘careful application of labour.’ The prison was duly completed and in 1859 it was inspected by the Governor.

Palace

In December 1884 a reporter of The Cape Argus was allowed to tour the prison and remarked that the former prison was ‘of the kennel order,’ while Roeland Street Prison was ‘quite the palace.’

He noted that the kitchen was equipped to make ‘soup of superlative excellence,’ or ‘rice water of homeopathic weakness.

His opinion was not shared in 1936 by a released prisoner who told The Argus the prison was rat-infested. They scampered over the huddled bodies at night and prisoners used to catch and suffocate them. A prisoner’s diet consisted of porridge, bread, soup and a little sugar.

In 1950, Mr W G Hoal, former Director of Prisons remarked: ‘Drop the atom bomb on it - that is the best thing that could happen to Roeland Street Prison.’

Epidemic

One of the prison’s most difficult times was during the influenza epidemic in 1918. The disease naturally attacked both prisoners and warders and within a few days it became a hospital. That was the only occasion when large quantities of brandy were served within the inhospitable grey walls. About 10 percent of the prisoners died.

Crowds gathered outside the prison on execution days to watch the flagpole. A black flag always fluttered minutes after the execution.

For the moment nobody knows what to do with the old building. One suggestion is that is should house the archives.

Preserved Old Entrance to the Roeland Street Prison (The Heritage Portal)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.