Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Watching a British quiz program recently, one of the questions posed to a participant was: “What is the study of facial hair referred to as?” The answer: Pogonology!

Even the electronic spell checker does not recognise this word, confirming that it is not a word in general use.

The thought that crossed my mind at that point was that the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC) contains many South African Cabinet Card format photographs dating from the Victorian and Edwardian eras containing examples of bearded South African men. Why not share these?

Therefore, all photographs included in this article are in Cabinet Card format, the most popular household photographic format between the 1880s and 1915. People typically placed these photographs in Victorian photo albums or frames in Victorian homes.

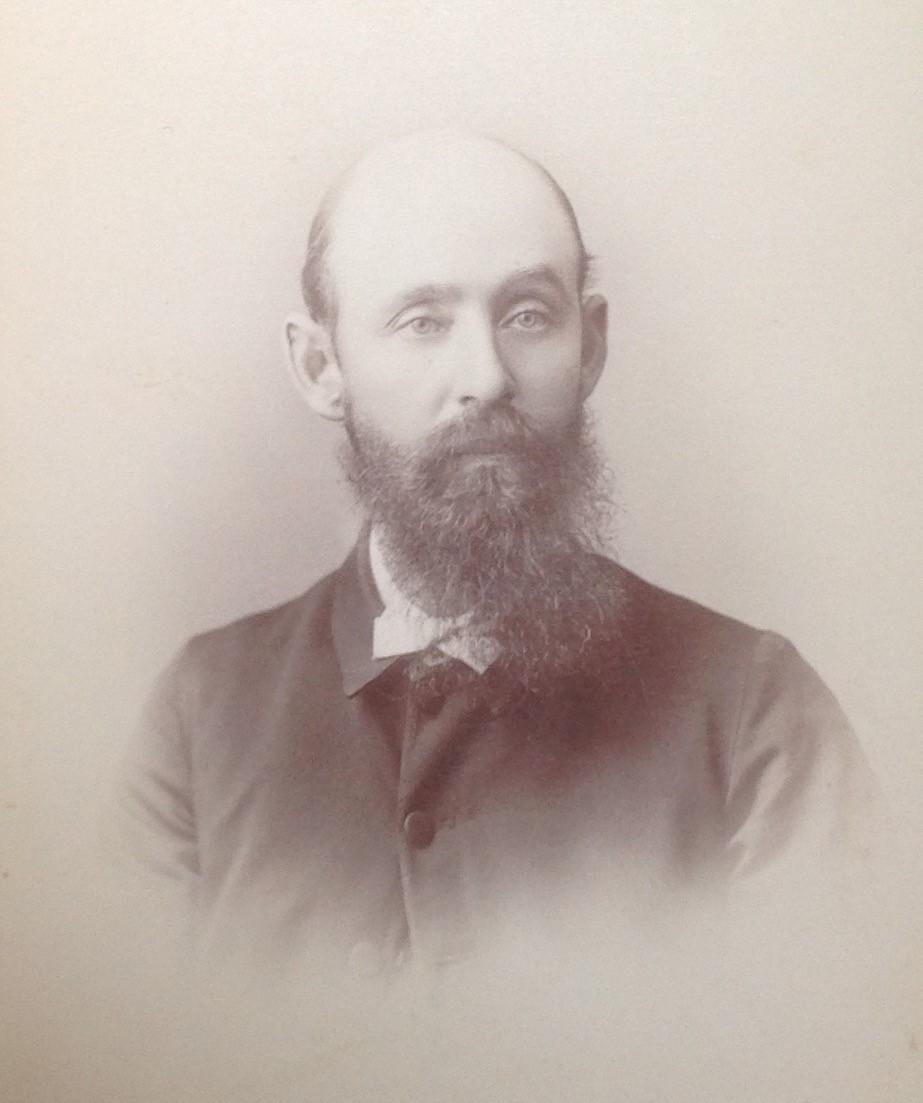

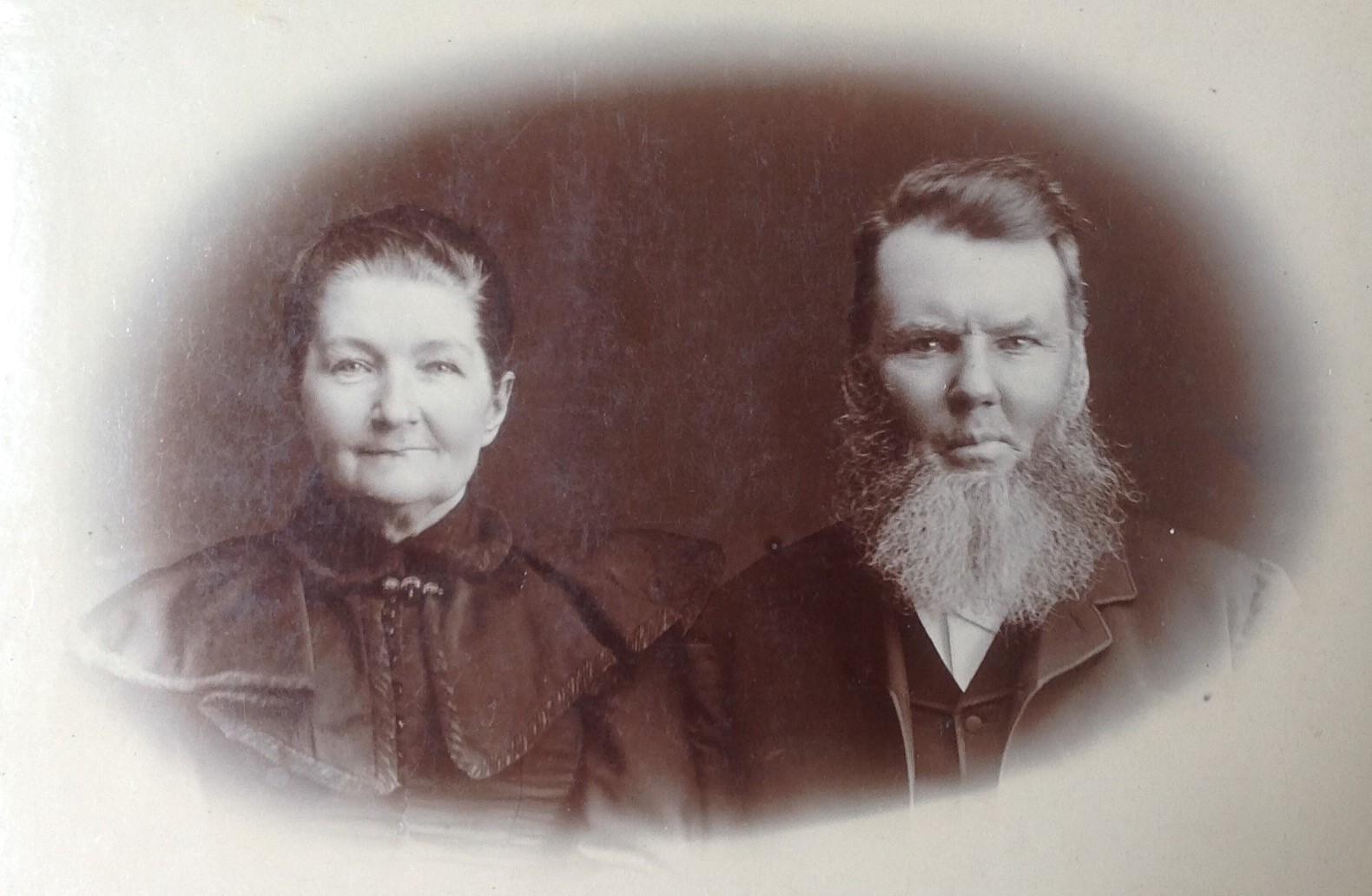

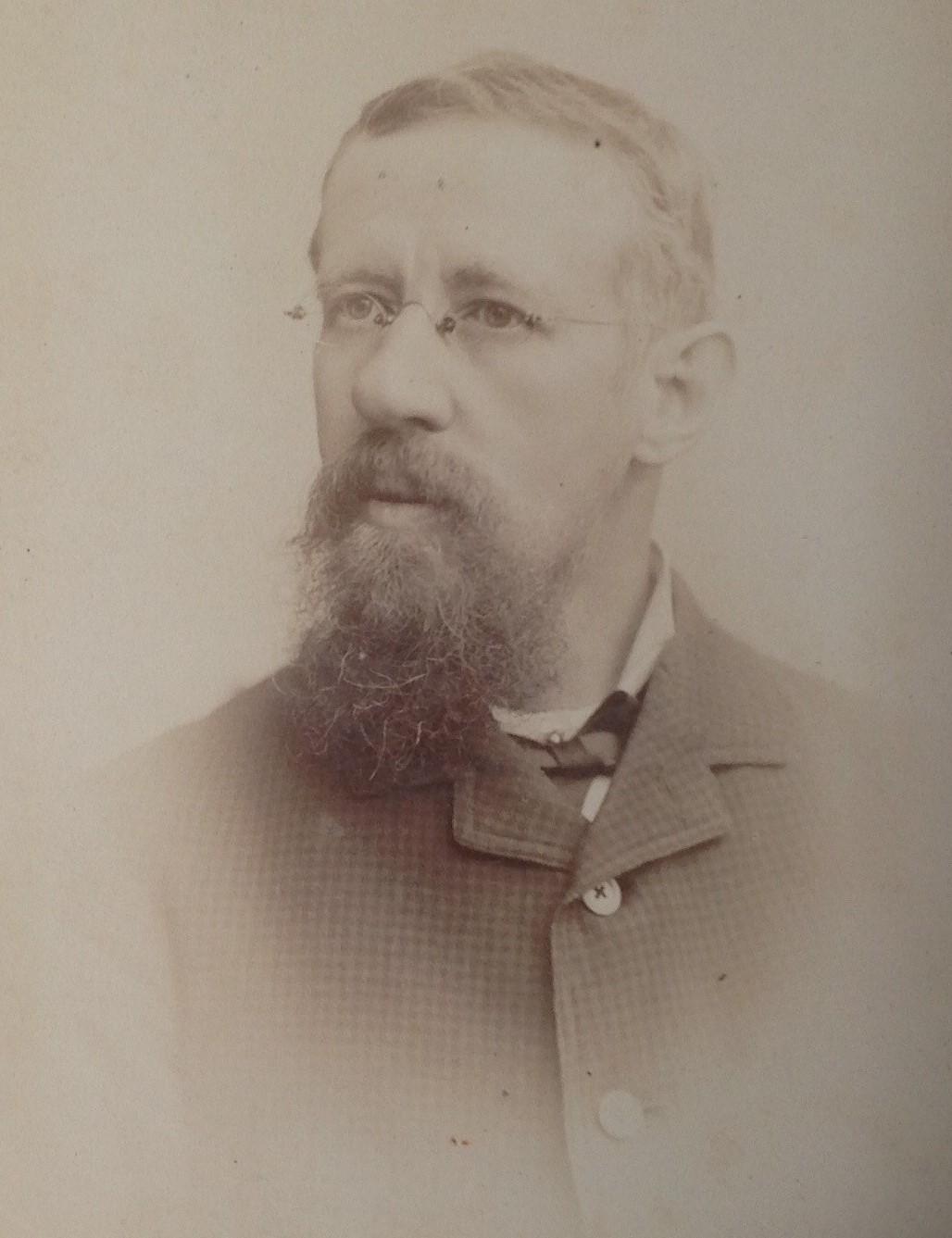

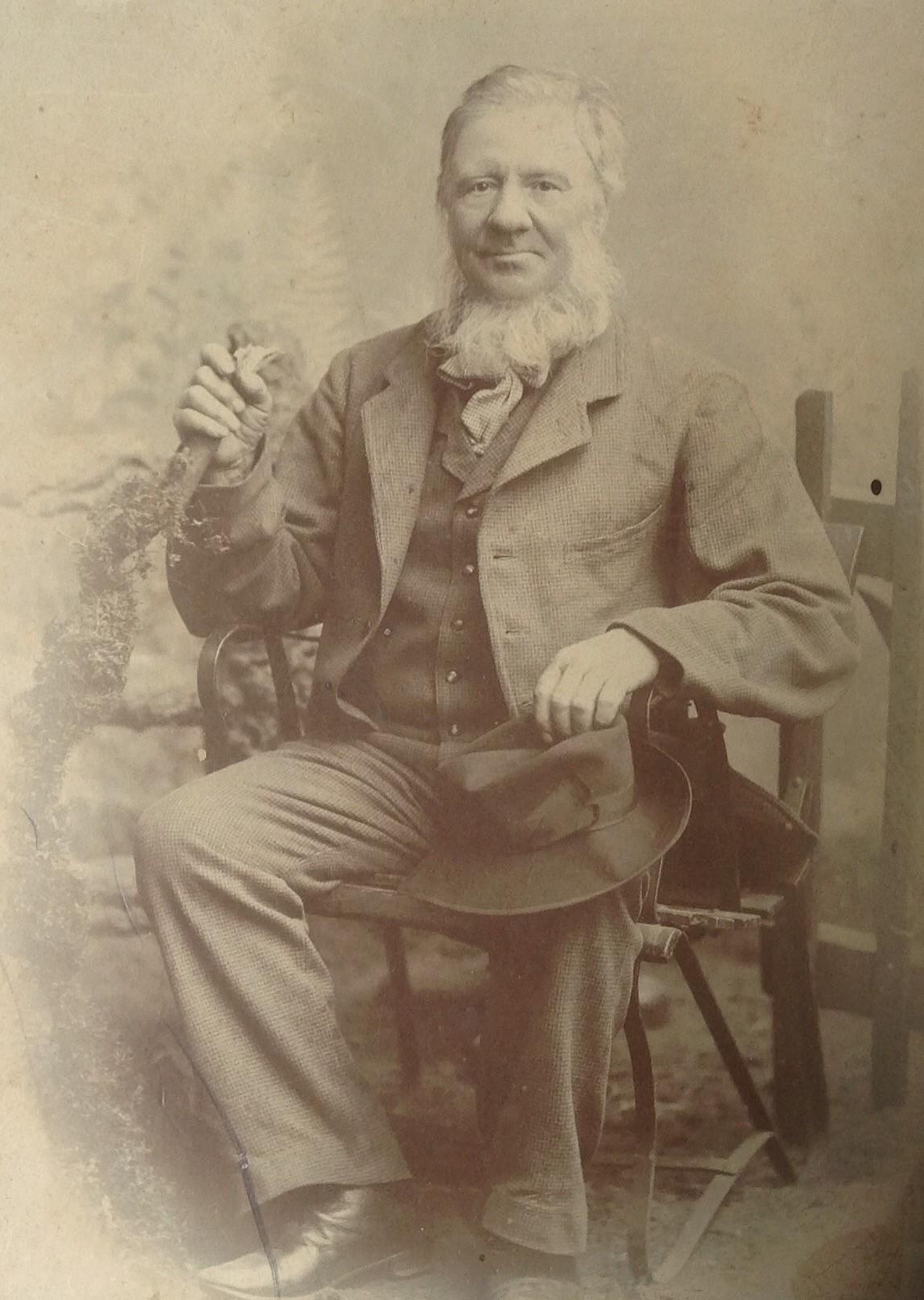

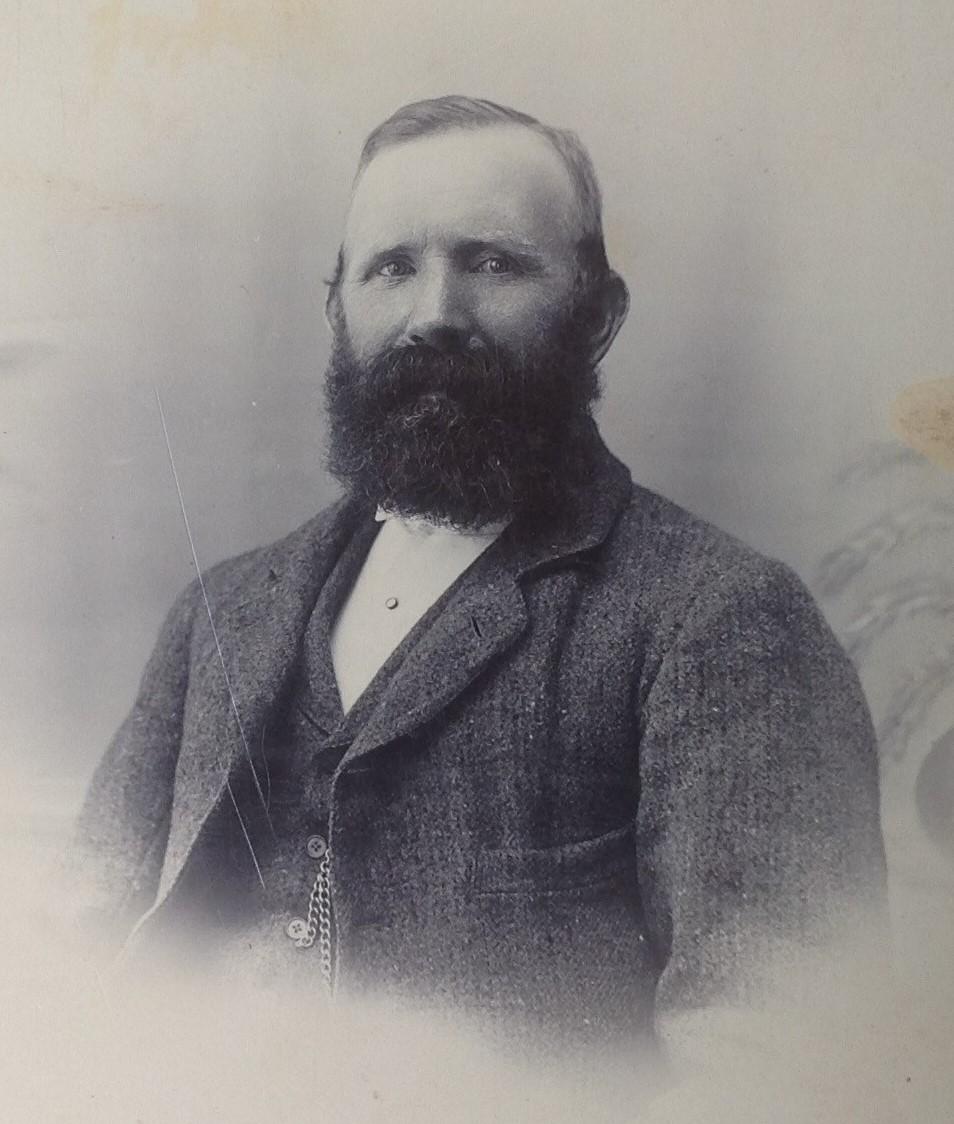

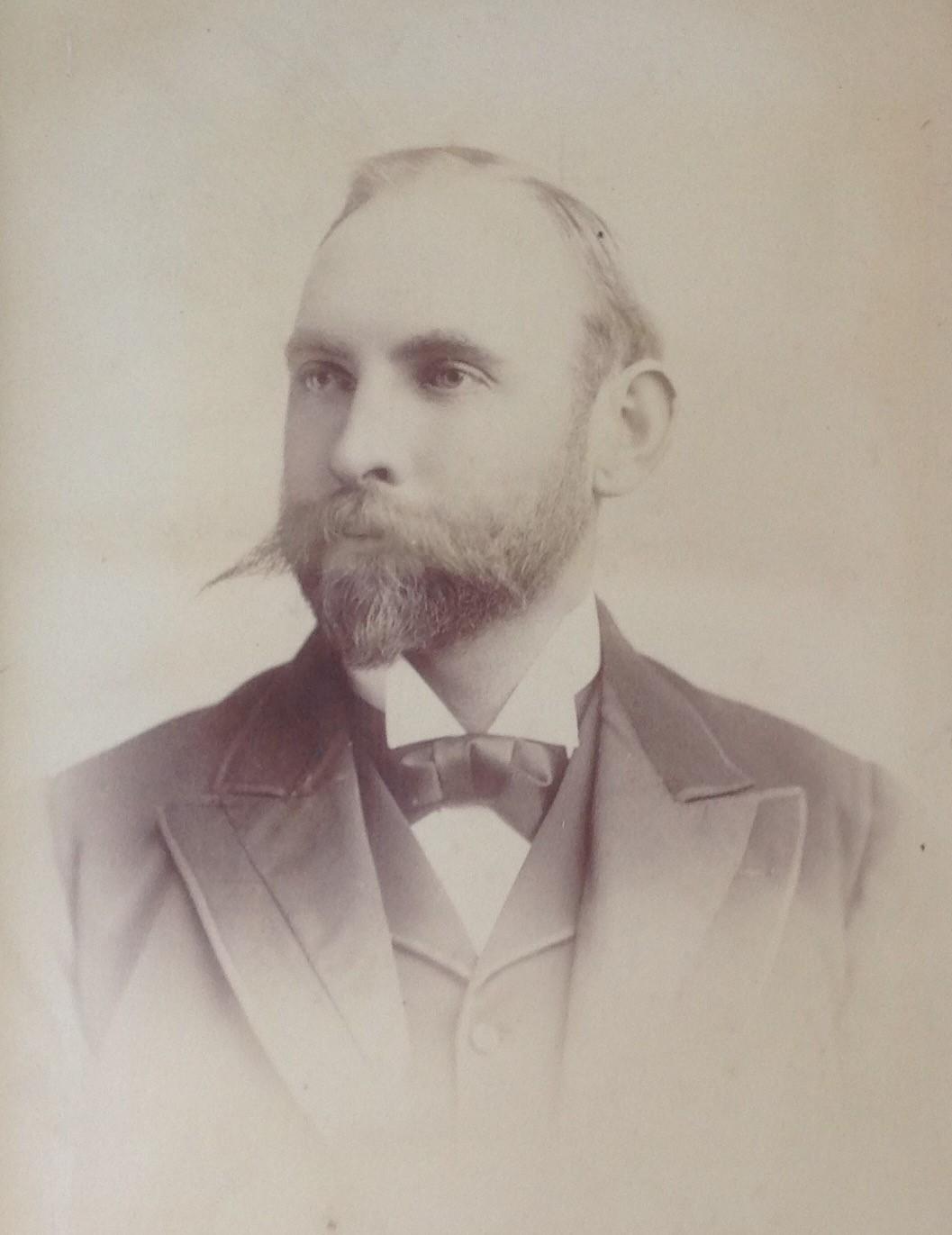

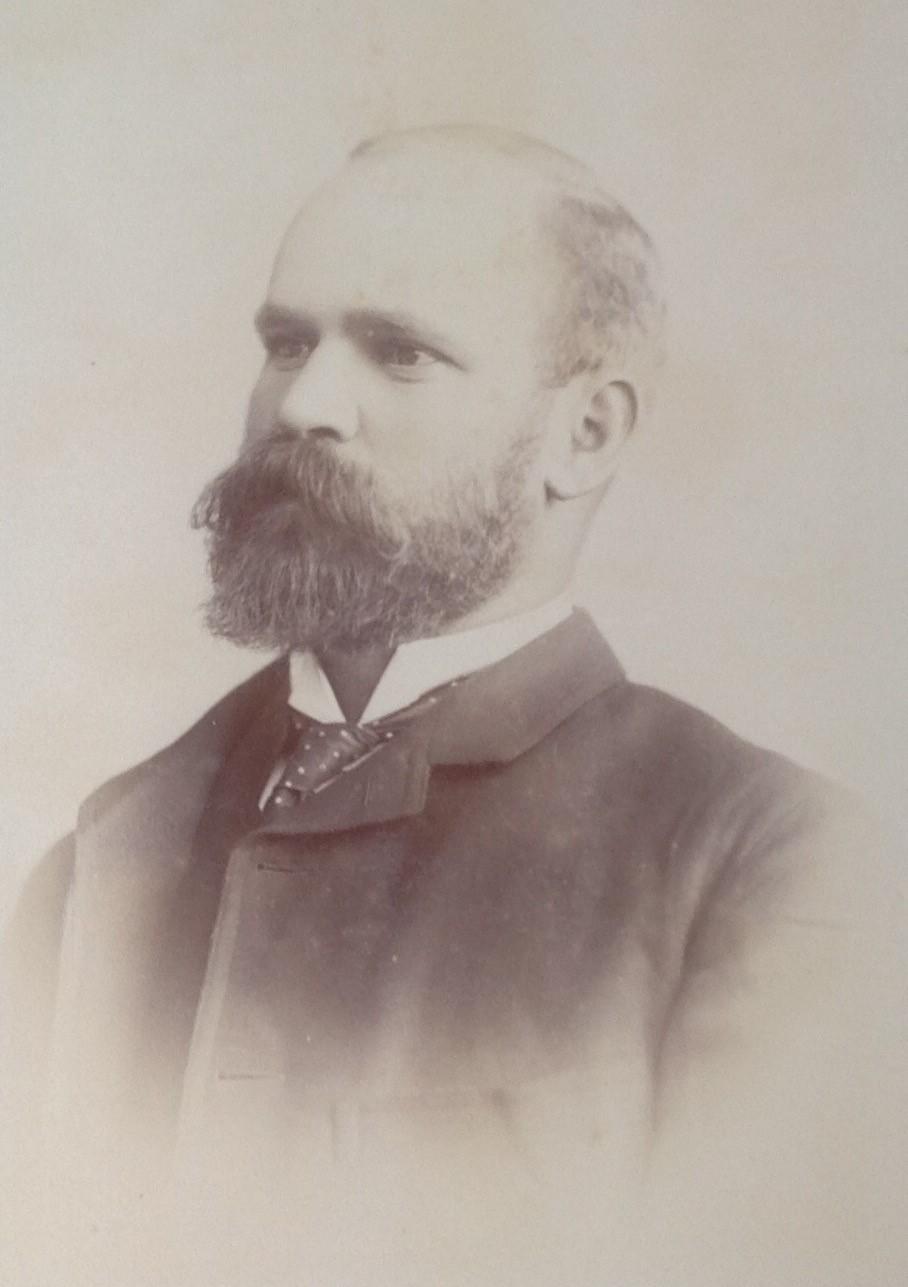

These 19th-century photographs explore some beards worn by the South African white male population. Some beards were proudly worn - neat and styled, whilst others came across as burly and unkempt.

While it may be prudent to do so, considering the title, it is not my intent to go into details about each beard’s cut, shape, and form as portrayed in the photographs shared in this article.

The psychology behind the beard

The fascinating aspect of facial hair is that it has no functional role to play. It remains ornamental because it has no specific physiological function to fulfil. Unlike other hair on our body, a beard does nothing other than fulfilling a deeper lying psychological aspect towards male masculinity.

University of New Mexico professor Geoffrey Miller, one of the preeminent evolutionary psychologists in the field, puts it this way:

The two main explanations for male facial hair are intersexual attraction (attracting females) and intrasexual competition (intimidating rival males).

Facial hair signals one thing to potential partners (namely virility and sexual maturity) and something else to potential rivals (formidability and wisdom or godliness). These signals combined confer their own brand of elevated status to the men with the most majestic moustaches or the biggest, burliest beards.

As a bearded person, I am somewhat jealous of the men out there who can grow real, fully-fledged beards; even some men in their early 20s beat me at it, confirming that I, therefore, certainly do not provide for any intrasexual competition.

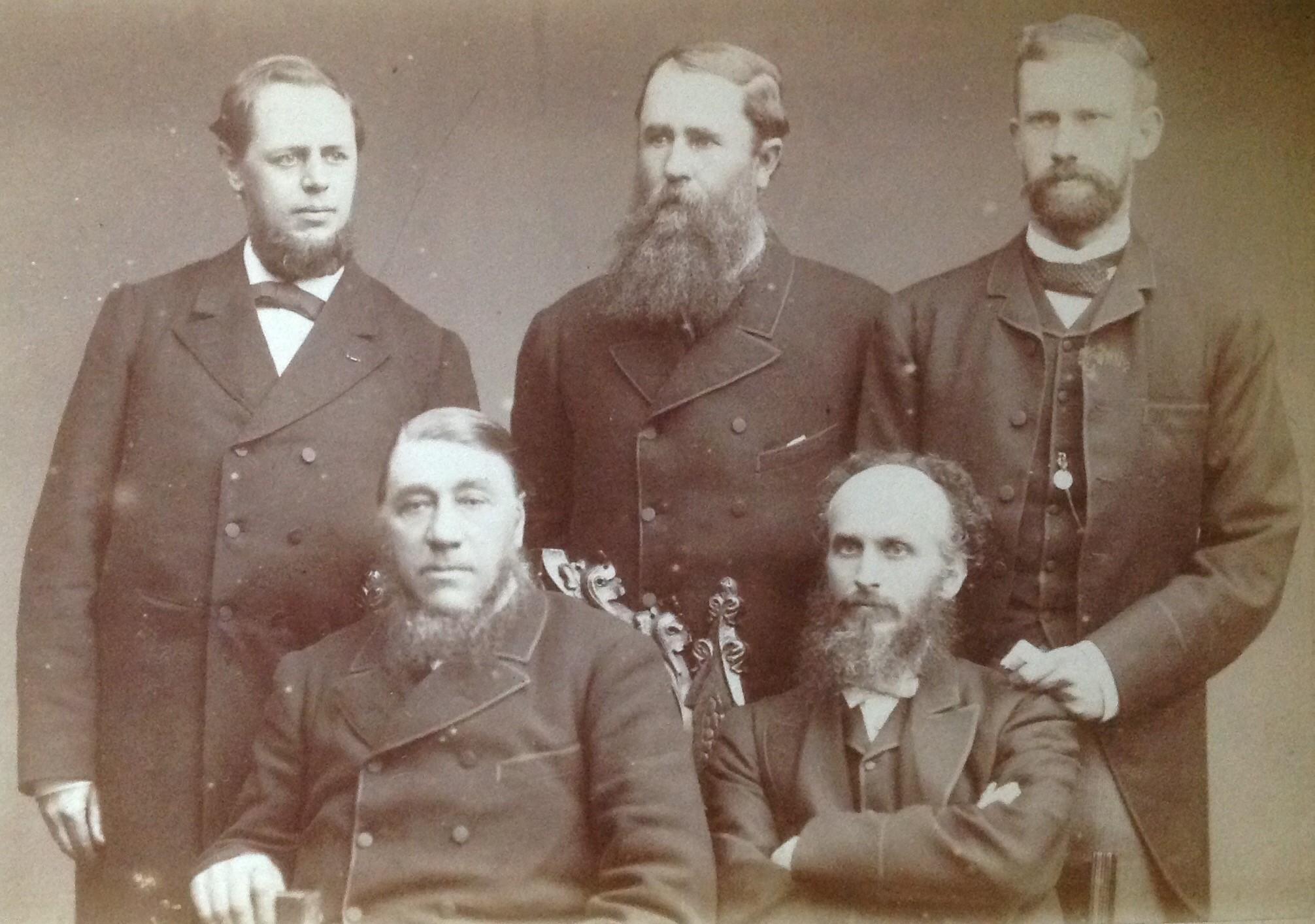

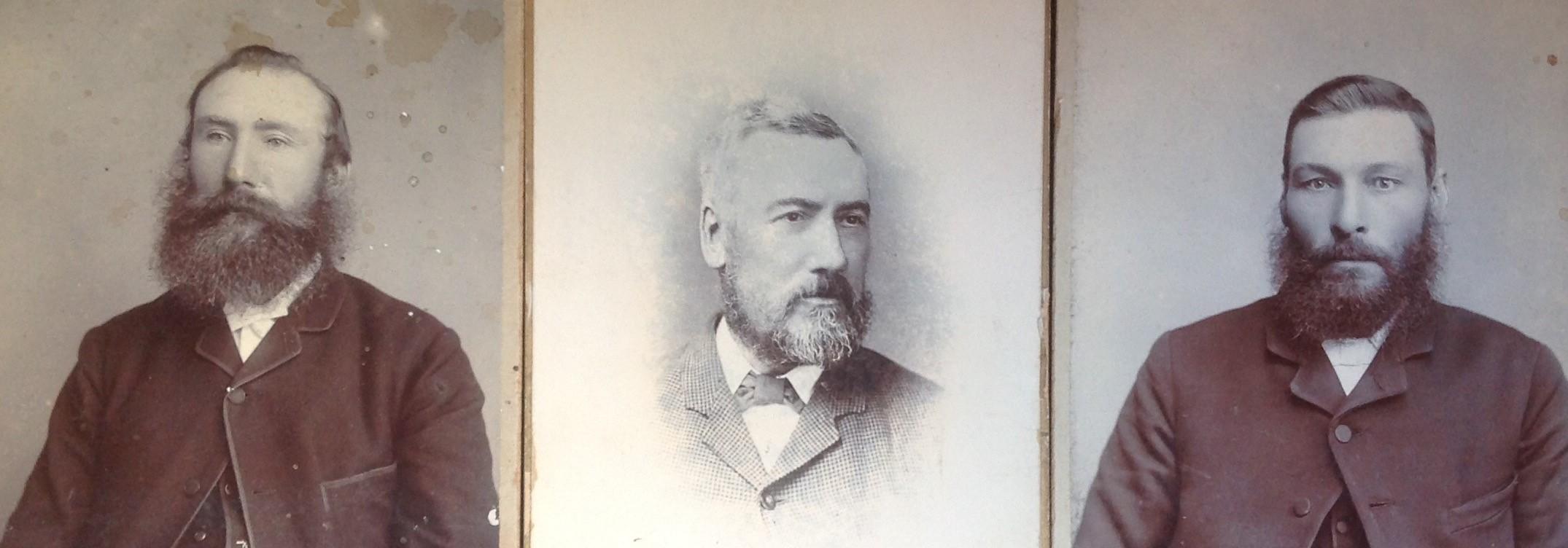

Paul Kruger and his bearded deputation. Photograph captured by London based Elliot & Fry. During 1884 Kruger headed a third deputation under which Britain recognised the South African Republic as an independent state. Seated from left to right: Paul Kruger and Reverend Stephanus Jacobus du Toit. Standing from left to right: Dutch legal advisor to the South African Republic, Gerard Beelaerts van Blokland, General Nicolaas Smit and secretary Ewald Esselen.

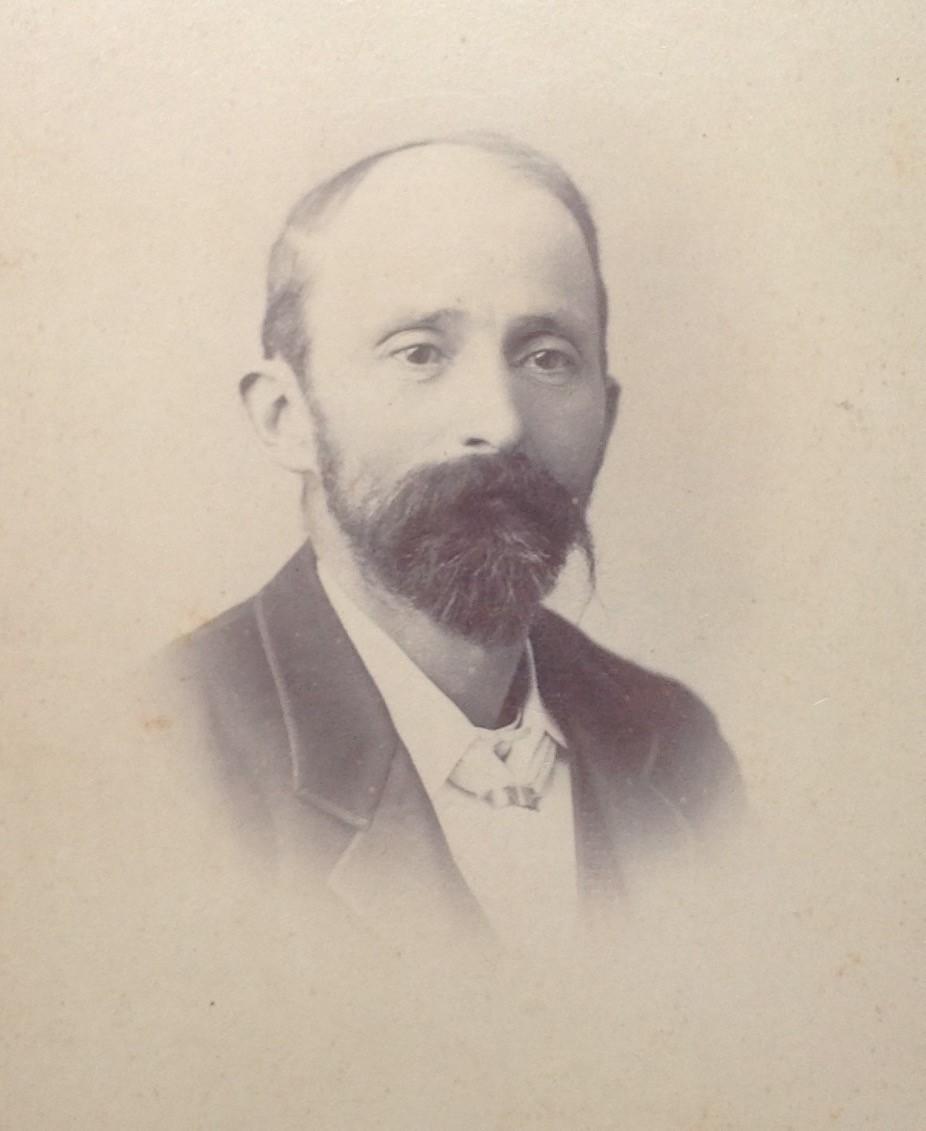

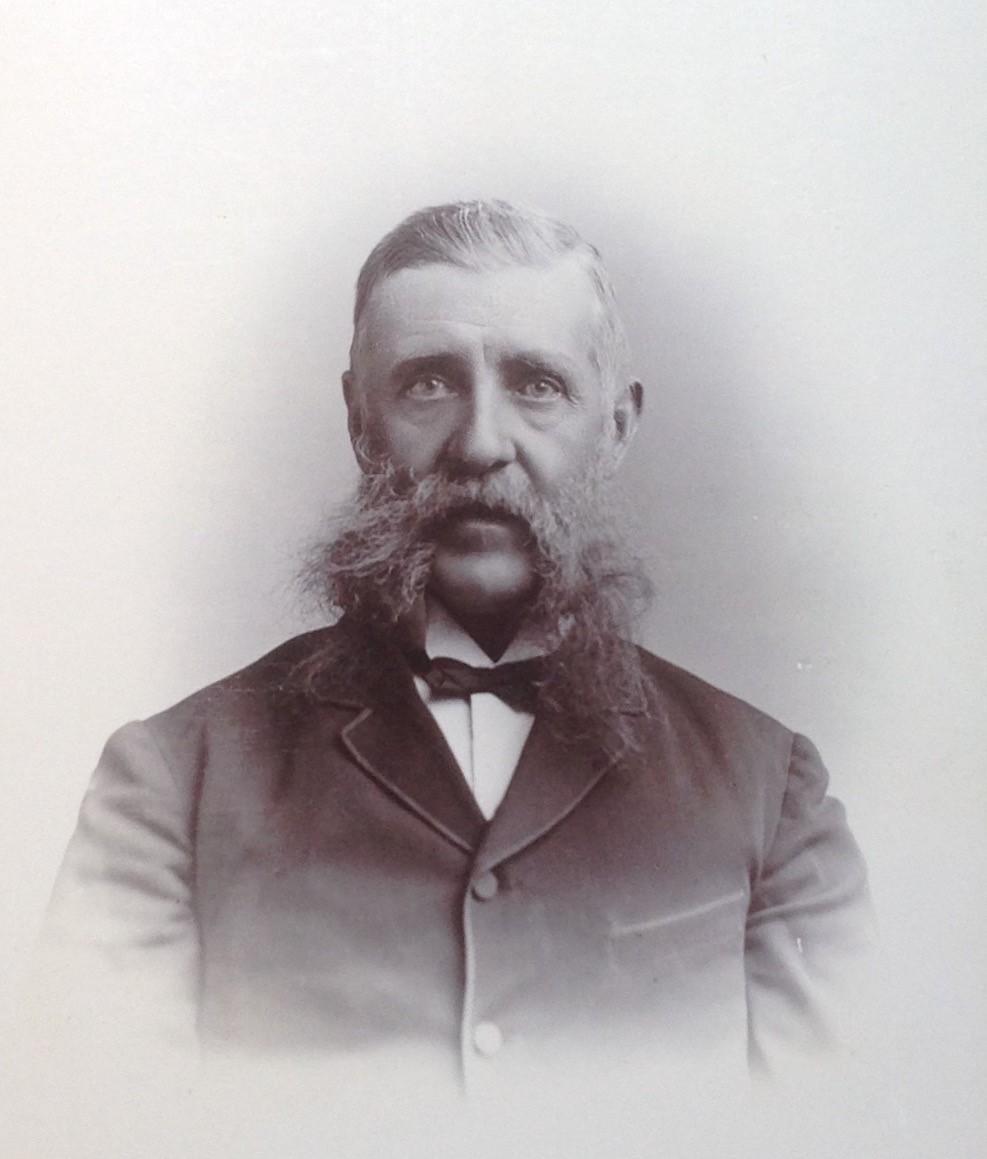

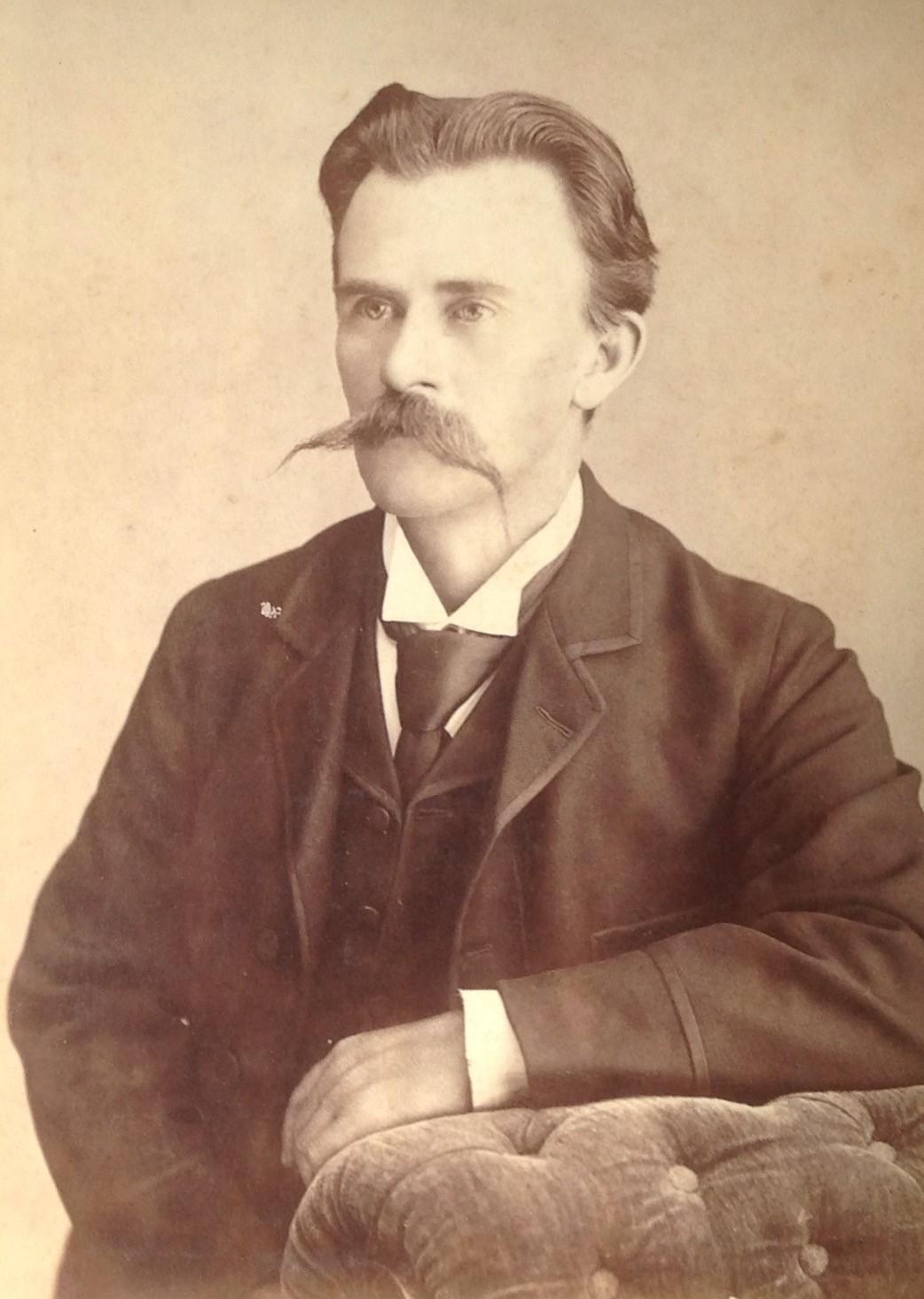

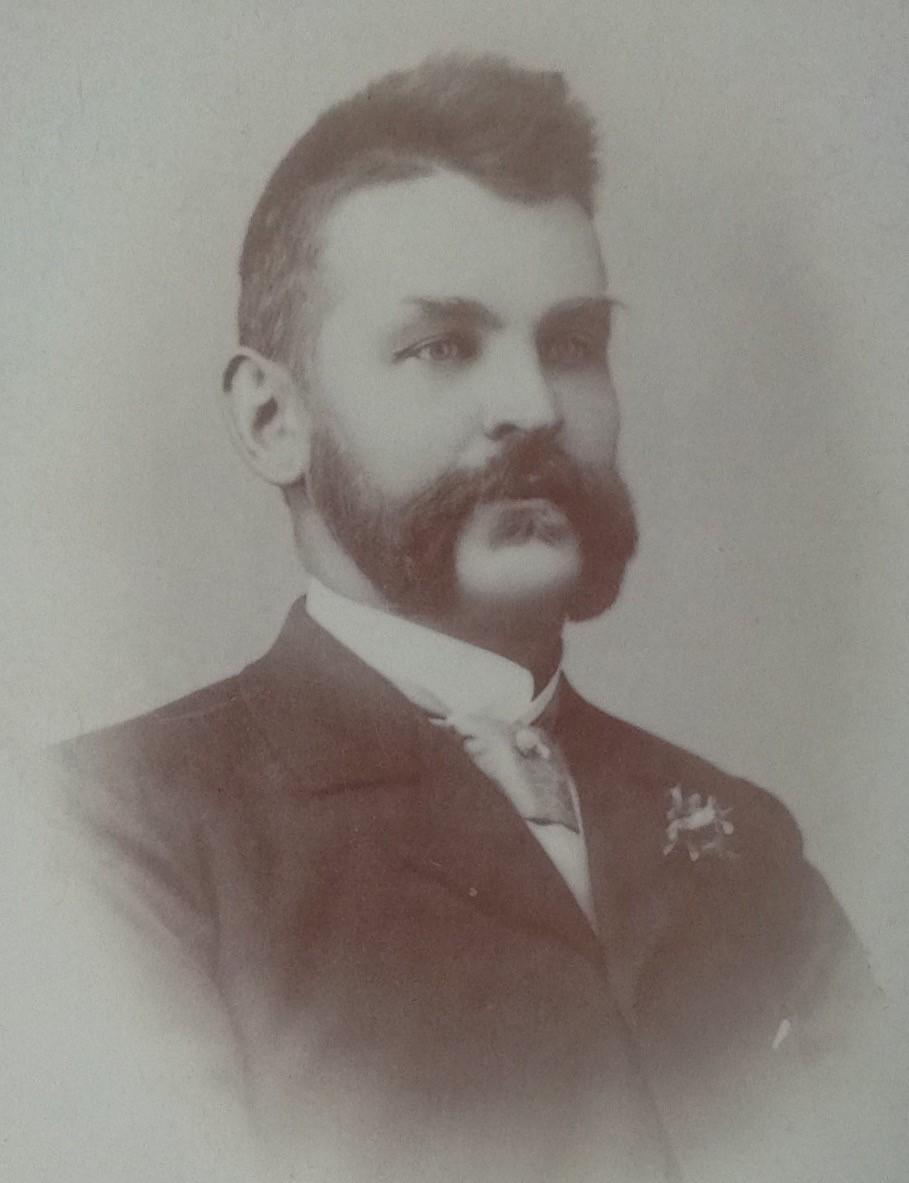

Now that is a moustache! Photograph of unknown male, by Caledon based WH Larkin.

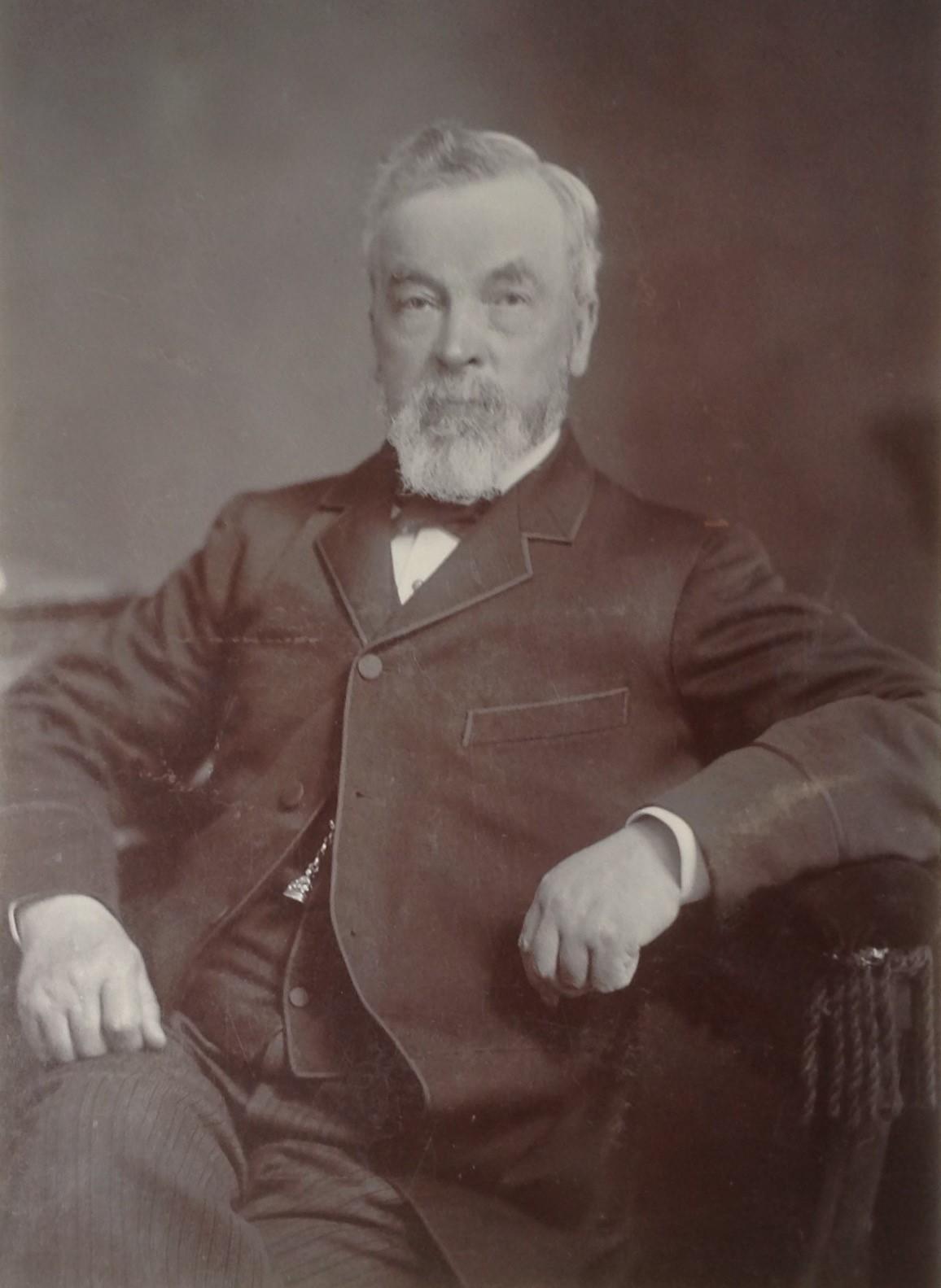

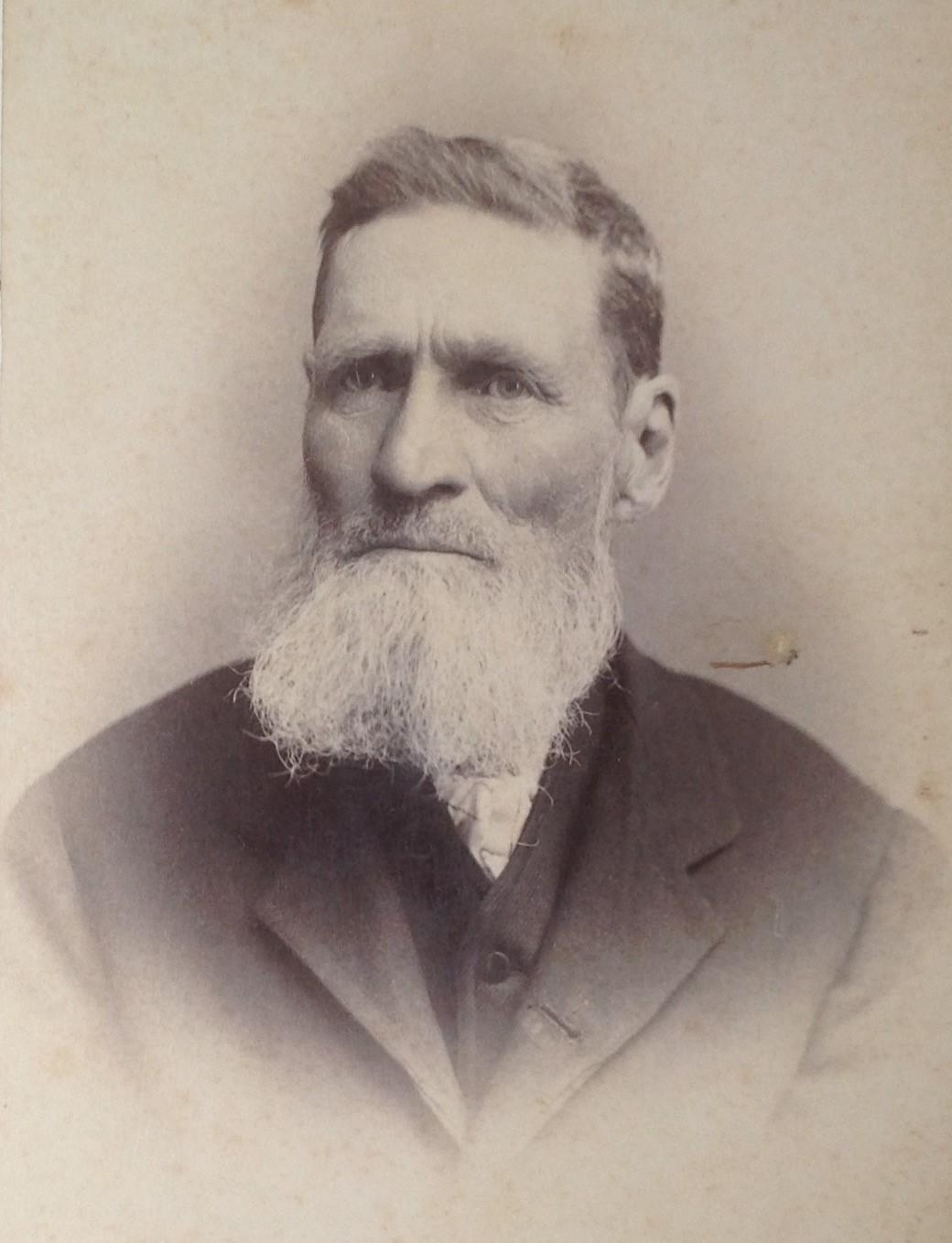

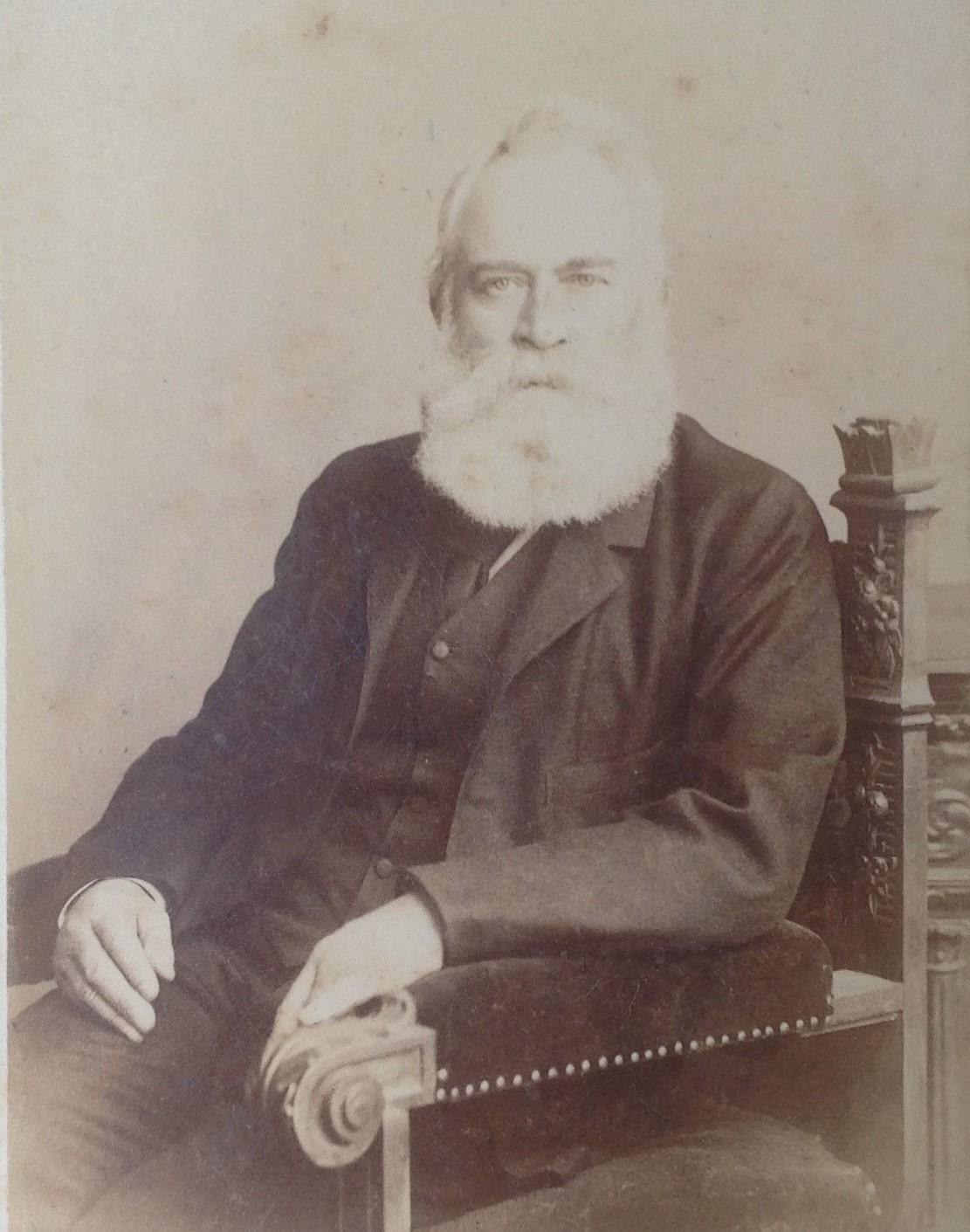

Dr Thomas Kitching (1838 – 1908) from Mosselbay by Cape Town based photographer SB Barnard

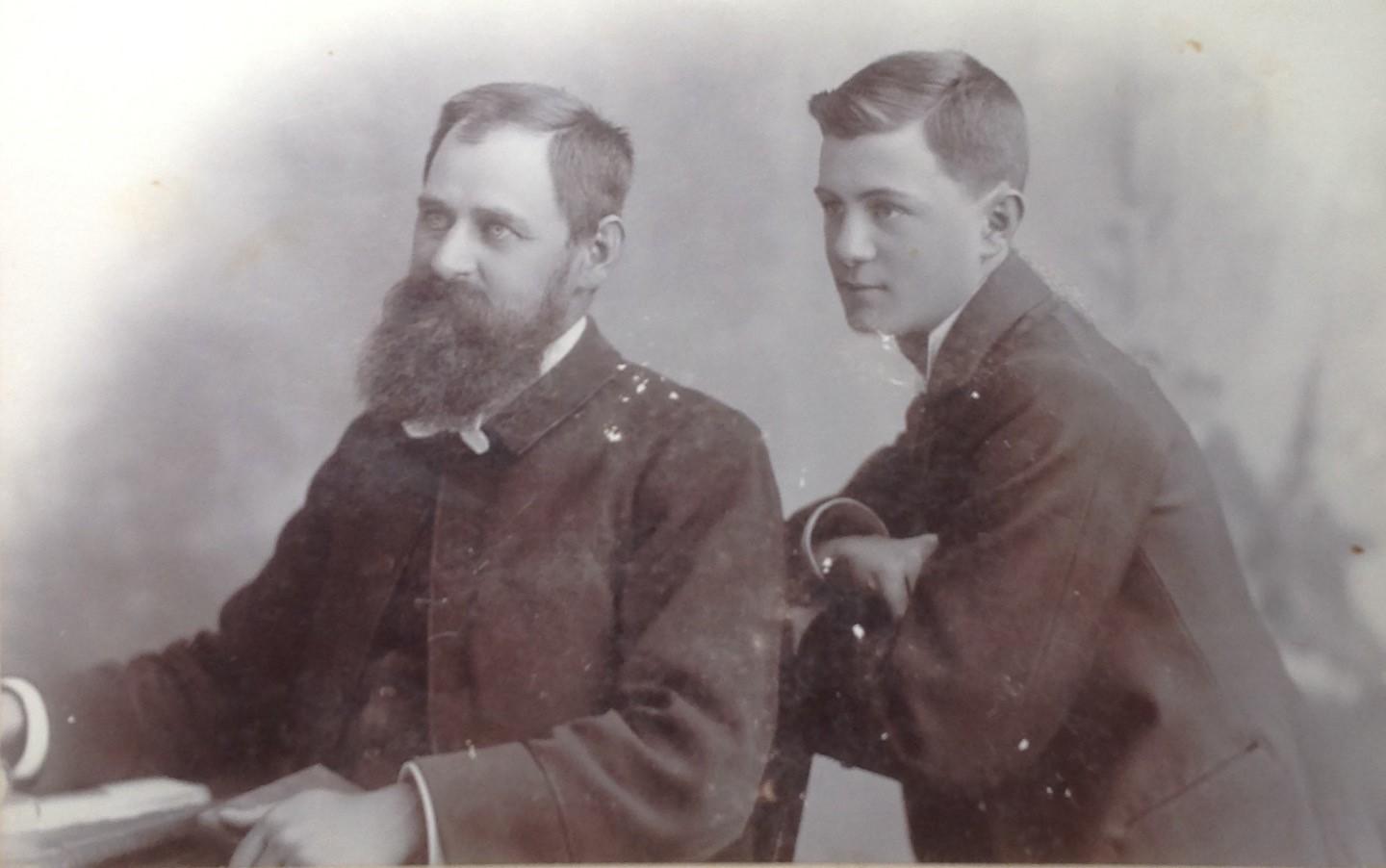

Unknown father and son by Cape Town based photographer Fripp

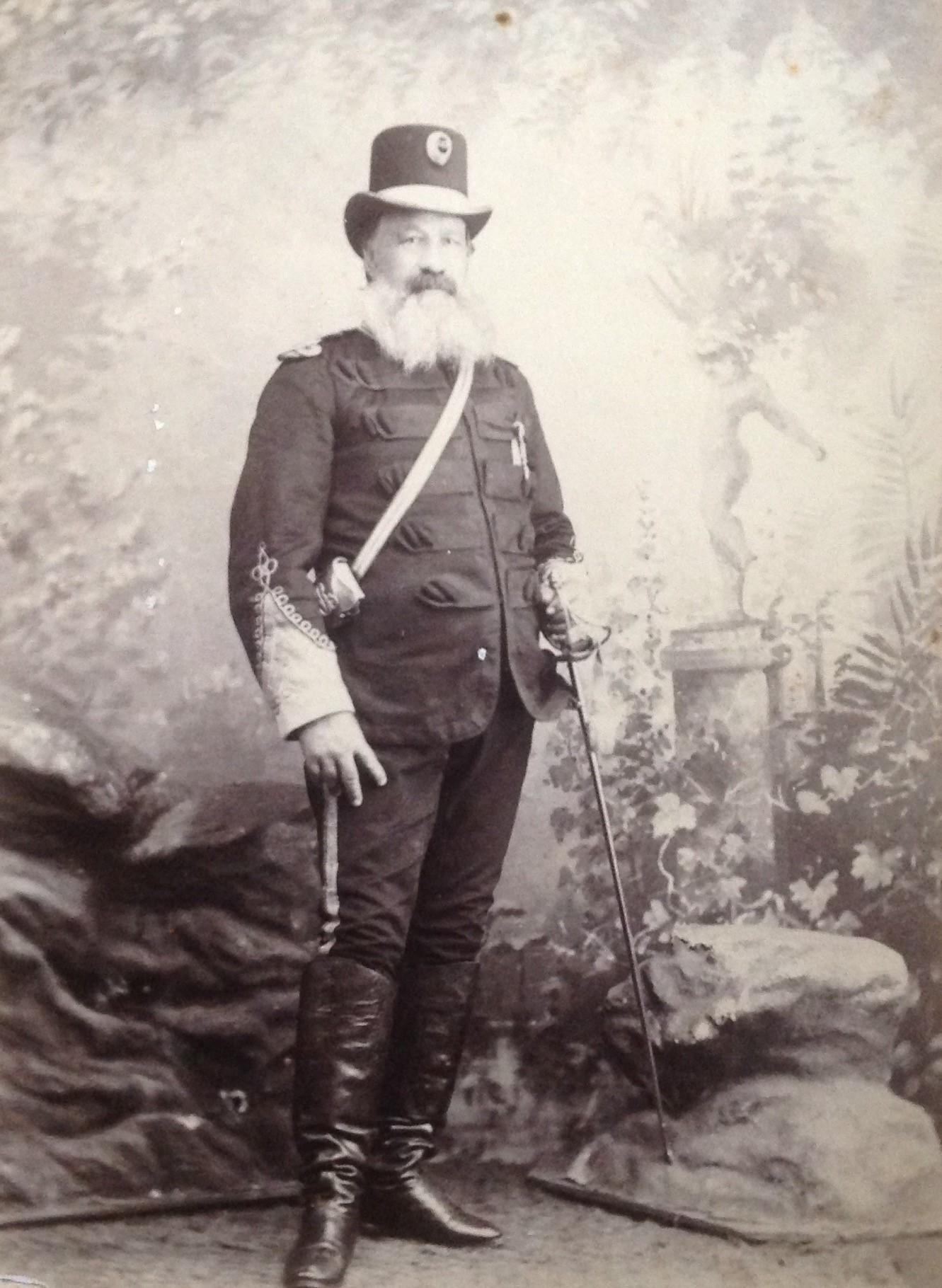

General Joubert. Note the colour difference between his beard and moustache. Joubert handed this photograph to Reverend FWR Gie during July 1892. Reverend Gie was based at the Barkly East NG Church. Photograph by Barberton based WH Caney & Co.

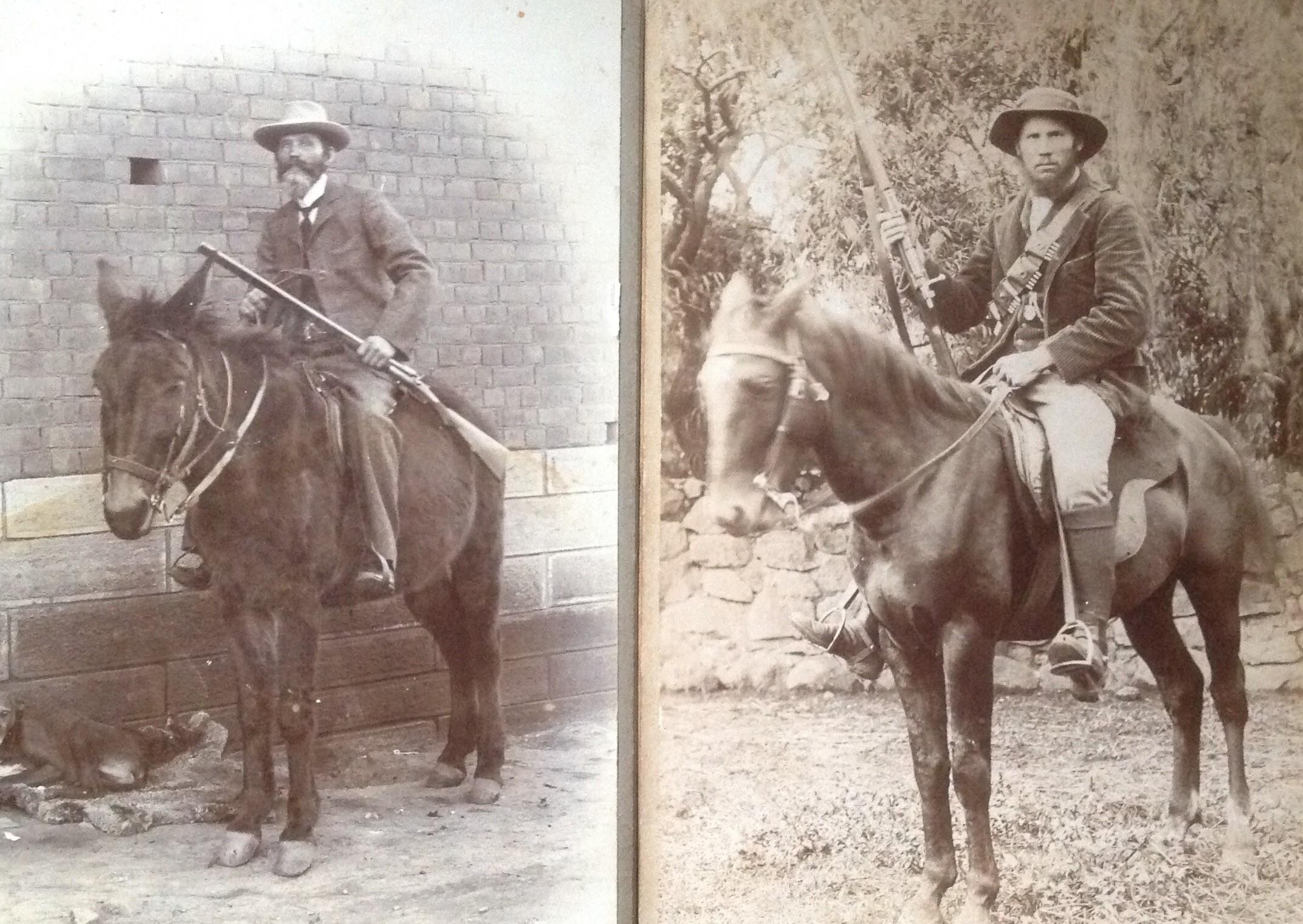

Hunter and Boer soldier on horseback. Photograph on right is of Boer soldier Gysbert Keet by Wakkerstroom based photographer Daubert. Man holding shotgun on left, as well as photographer are unknown

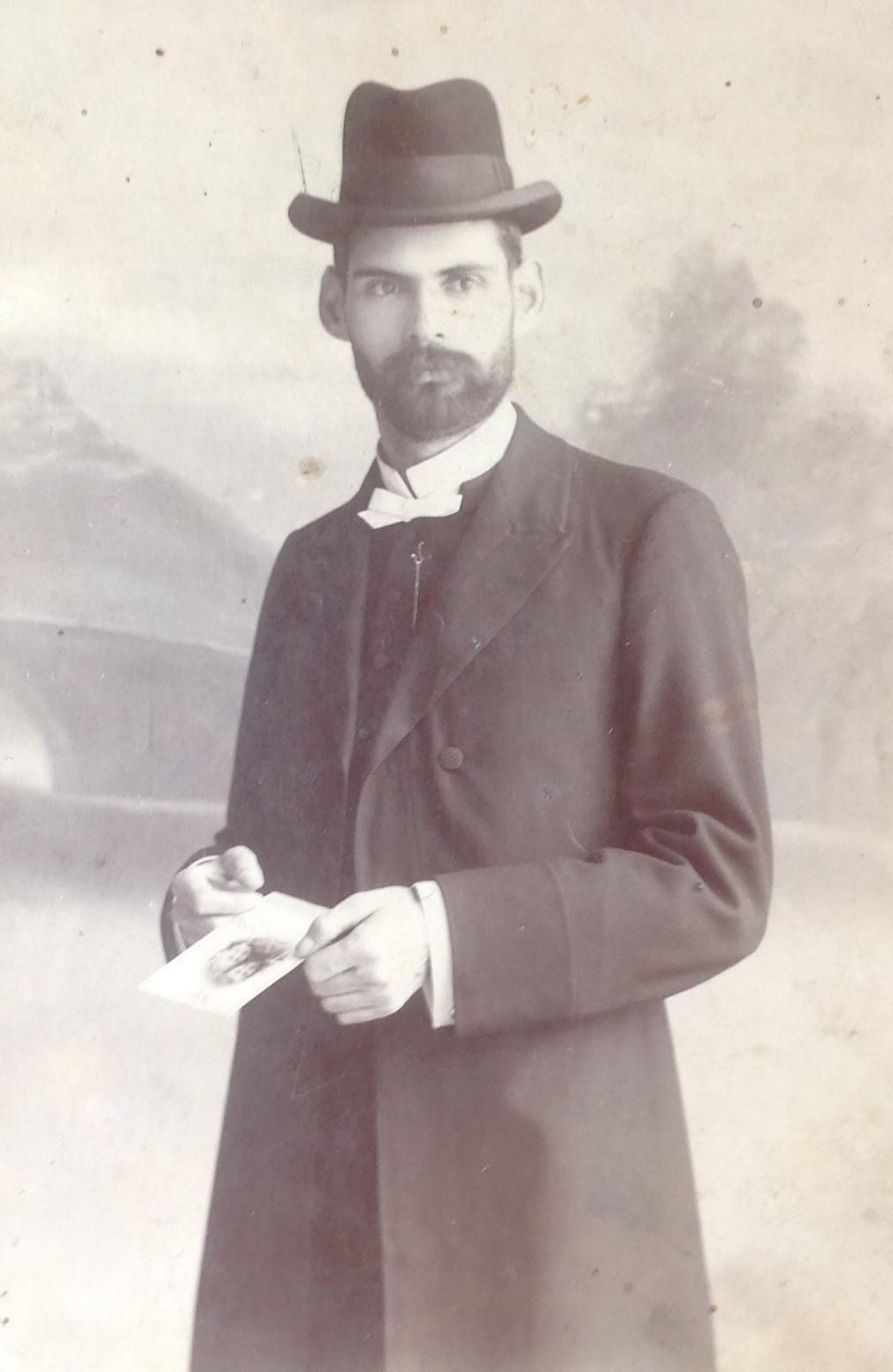

Photograph of unknown gentleman holding a cabinet card format photograph of loved ones. He looks rather priestly. Photograph by Beaufort West based photographer ED Edgcome

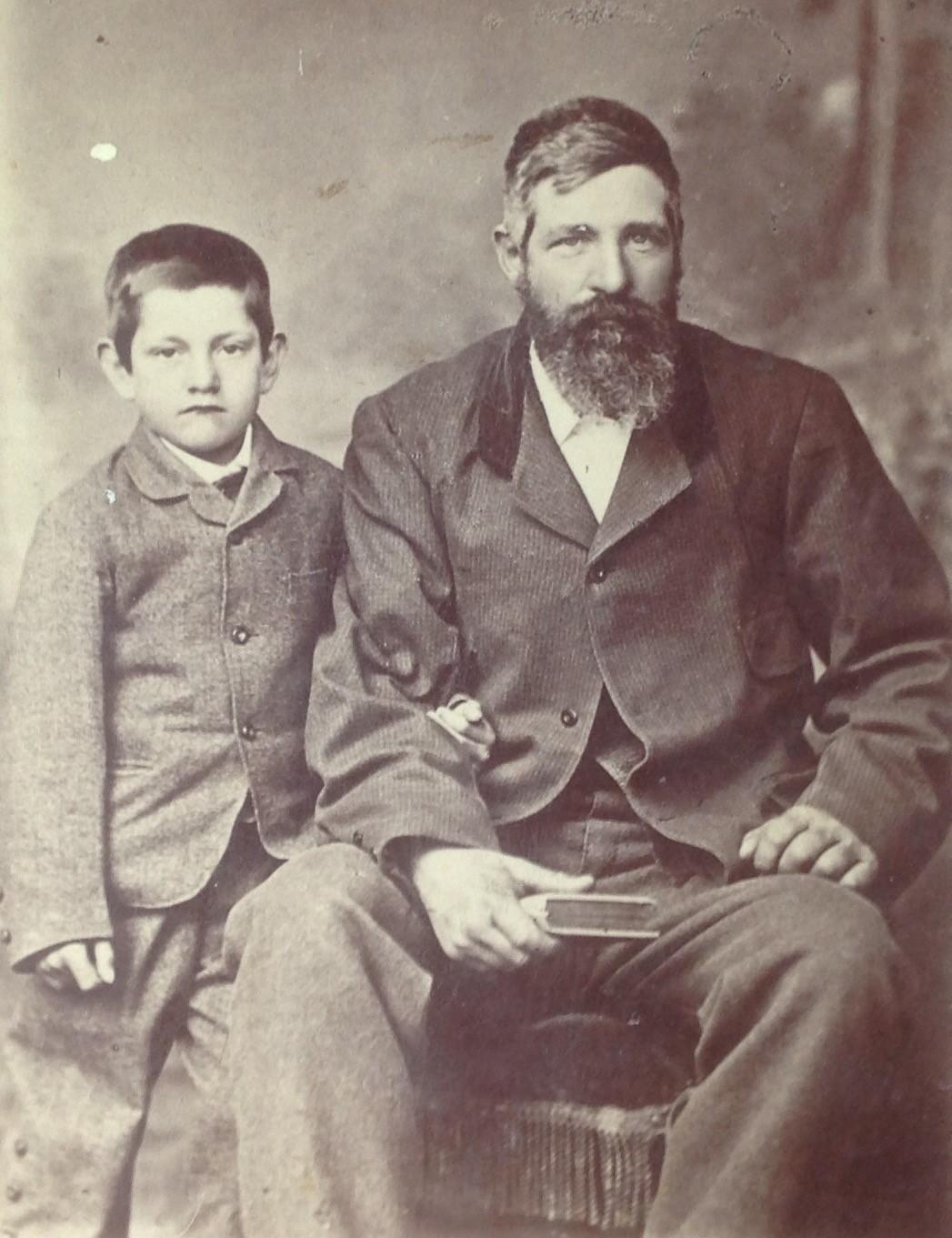

Father and son by Graaff Reinet based photographer William Roe. What was once a dark beard is now in the process of greying. The affectionate pose of the little one standing hooked in with his father is rather unusual.

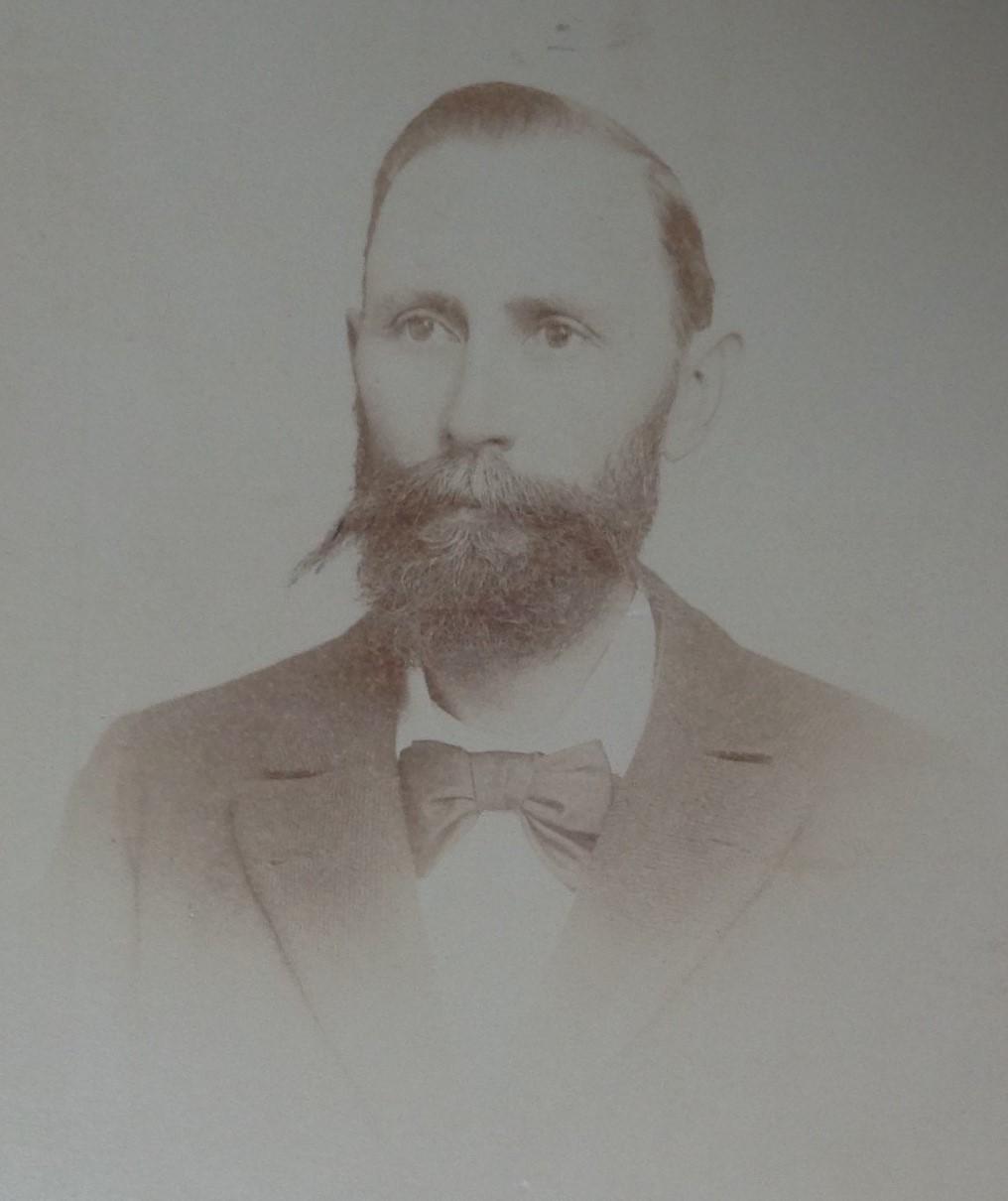

Unknown gentleman with an interesting beard style. Photograph by Grahamstown based Hepburn & Jeanes

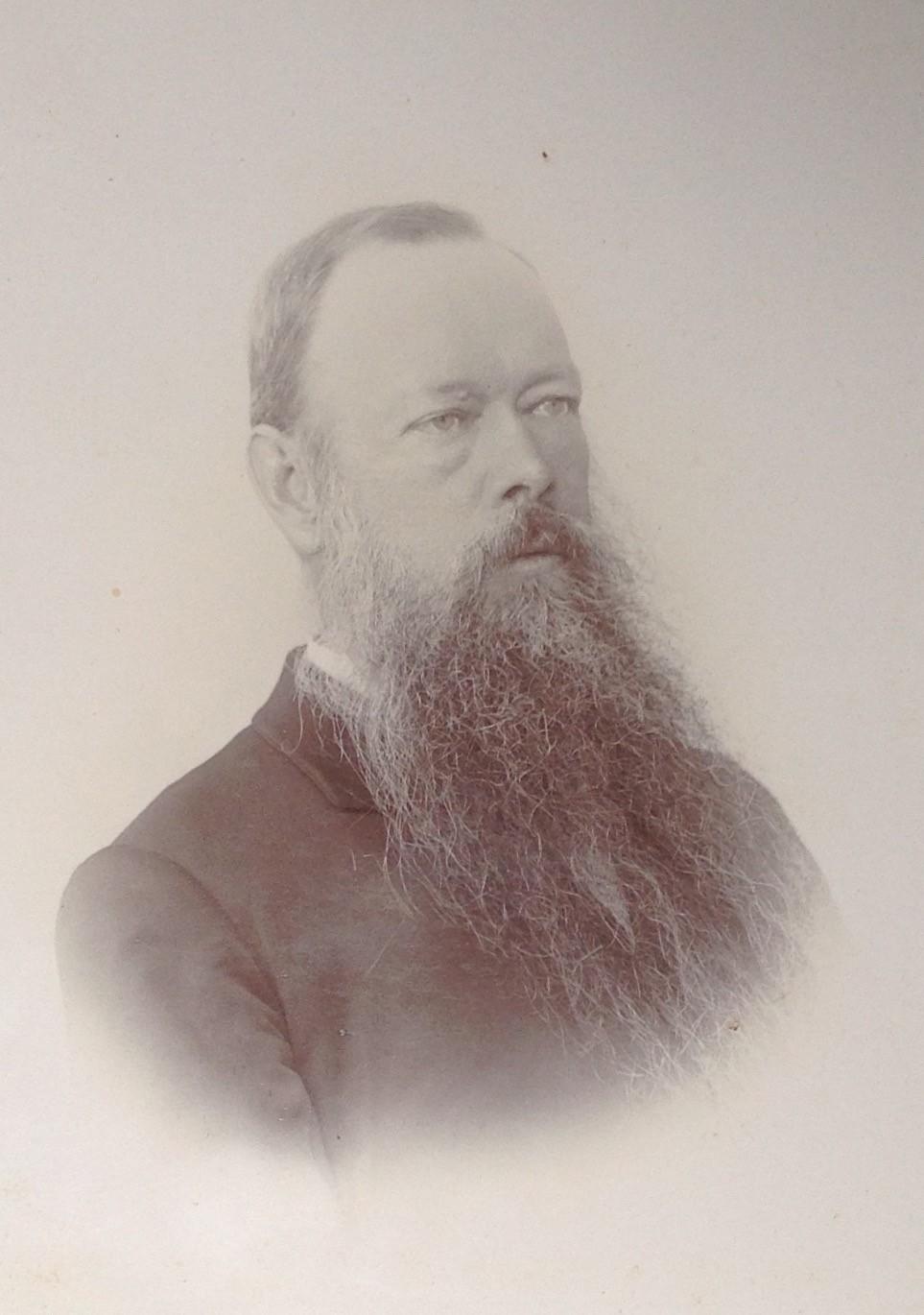

Whilst some have neatly trimmed beards, others, like this unknown gentleman was not too bothered. Photograph by Grahamstown based Hepburn & Jeanes.

Brief world history

Beards have been around for as long as humans. Still, their cultural significance, associations, and status have varied hugely throughout the centuries.

Many religious male figures have facial hair; for example, numerous prophets mentioned in the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) were known to grow beards. Other religions, such as Sikhism, mandate growing beards. Amish men grow beards after marriage but continue to shave their moustaches to avoid historical associations with military facial hair due to their pacifistic beliefs.

Throughout history, men have donned facial hair or shaved it as a response to the choices of their enemies and rivals. The ancient Romans, for example, went clean-shaven for 400 years because the ancient Greeks, their opponents during the Hellenistic Period, celebrated beards as symbols of elevated status and high-mindedness.

Englishmen went clean-shaven as a cultural reaction to their bearded Viking invaders. From AD 793 to AD 1066, the English lived under the threat of Viking invasion (and, in some parts, actually lived under Viking rule), tellingly called “the Viking Age of Invasion”. During the Protestant Reformation, many Protestants grew out their beards in protest against Catholicism, whose priests were typically clean-shaven.

Depending on the Period and country, facial hair has been prohibited in armies or, on the contrary, became an integral part of the uniformed man.

A fascinating snippet is that Russian Emperor Peter I decided in 1705 that a man wearing a beard needed to be taxed. The social standing of Russian male citizens with beards determined the quantum of such tax. Only priests were not taxed.

Victorian Masculinity

Before the mid-19th century, beards were seen as a sign of degeneration, only to become an ultimate sign of class, sophistication and fashion.

Mercer Adams, a professional and successful doctor, described the beard as the 'badge of manly strength and beauty'. It became a way to define 'manliness' during a period when gender identity was beginning to change. Men began sporting huge beards, such as the one famously depicted by Charles Darwin.

The lengthy Victorian Period resulted in various beard trends, many of which still inform our opinions of beards today.

Beard styles often reveal a moment in time. Yet, no single beard style in the Victorian Period stood out in South Africa.

People during the Victorian era held different views about the potential health risks of having a beard.

One view was that beards are germ magnets, which trap bacteria in an unhygienic nest around the mouth and nose. So much so that early research suggested that beards might lead to the spread of infectious diseases. For example, saliva caught in the hairs of the beard could contain tuberculosis. With contact, the disease could pass from person to person.

Another opposing stance, however, was that some doctors encouraged men to grow beards to act as a filter against germs. Doctors believed a beard stopped harmful substances from getting into the mouth and throat and attacking the teeth.

By the way, to have pulled a man’s beard pre the Victorian era was seen as a huge insult. I think this is still the case today – for those of us who have long enough beards to be pulled.

Unknown bearded gentleman. Photograph by Aliwal North based photographer Dugmore

Unknown bearded gentleman. Photograph by Bloemfontein based photographer Deale.

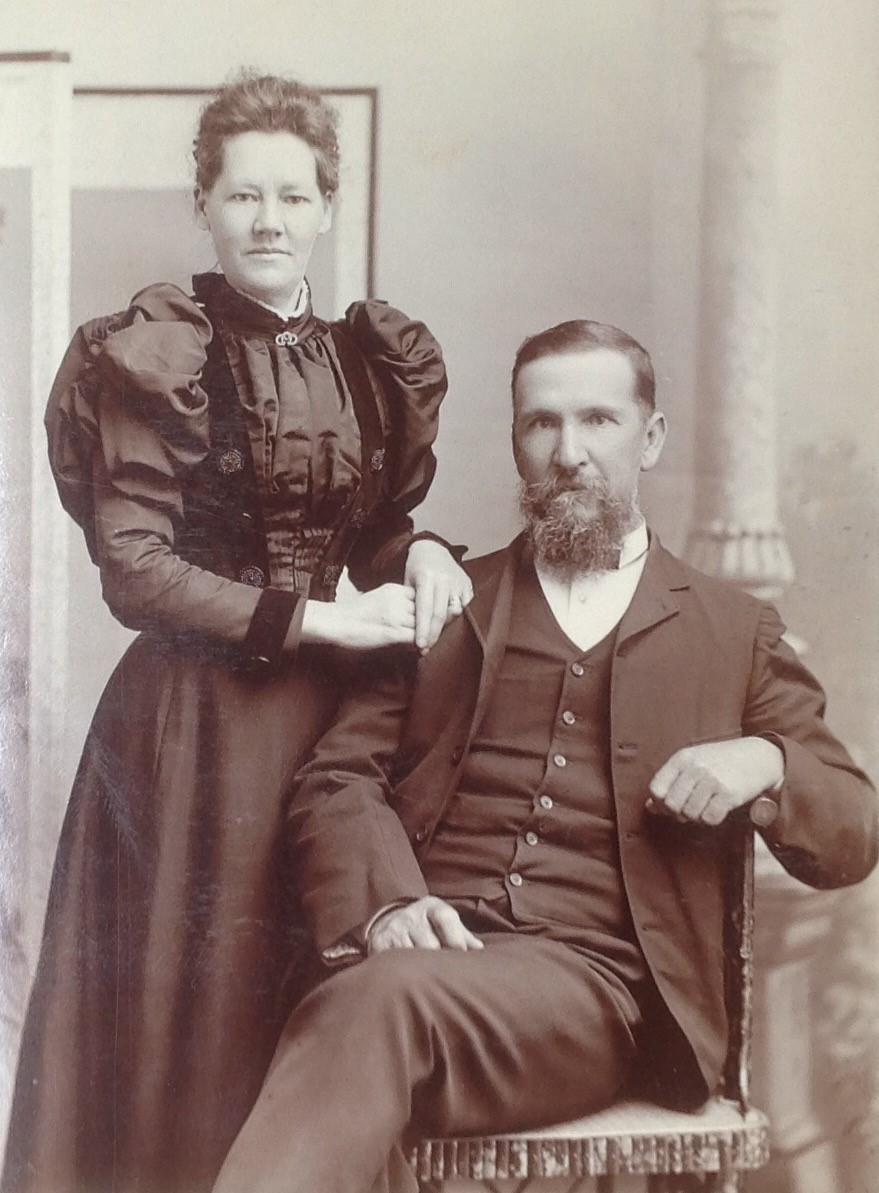

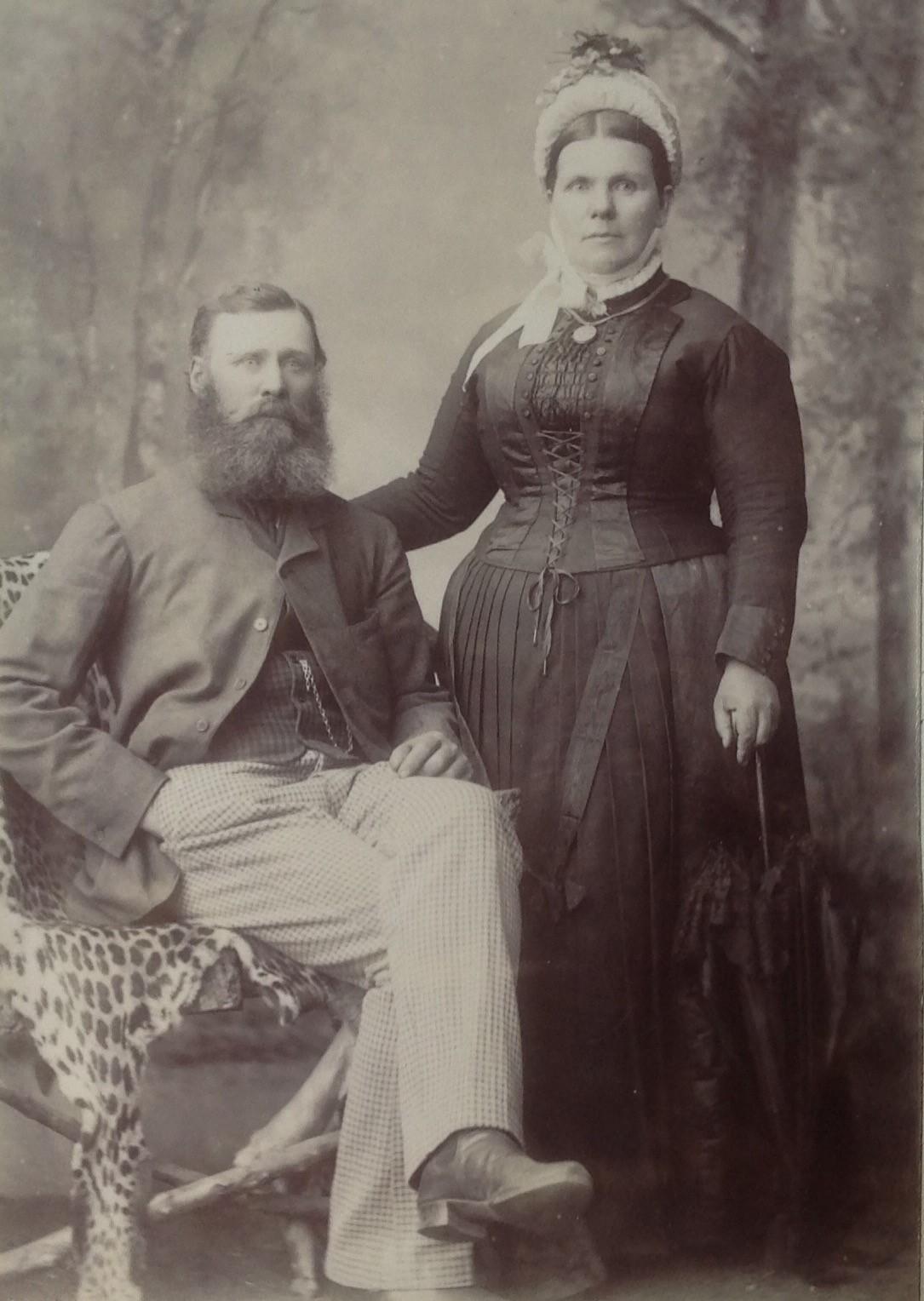

A grey bearded and very Germanic looking gentleman photographed with his wife. Photograph by Burgersdorp based photographer L Friedenthal (From The Albert Art Studio)

Unknown couple by Barrydale based photographer Paul Schou. Just look at that moustache.

Unknown couple. Note his rather unusual beard and moustache combination. Photographer unknown.

Attractive couple in a rather unusual pose. Photograph by Durban based WB Sherwood.

Unknown gentleman with a rather wild beard. Photograph by East London based Morley.

Unknown couple. Photograph by East London based Morley.

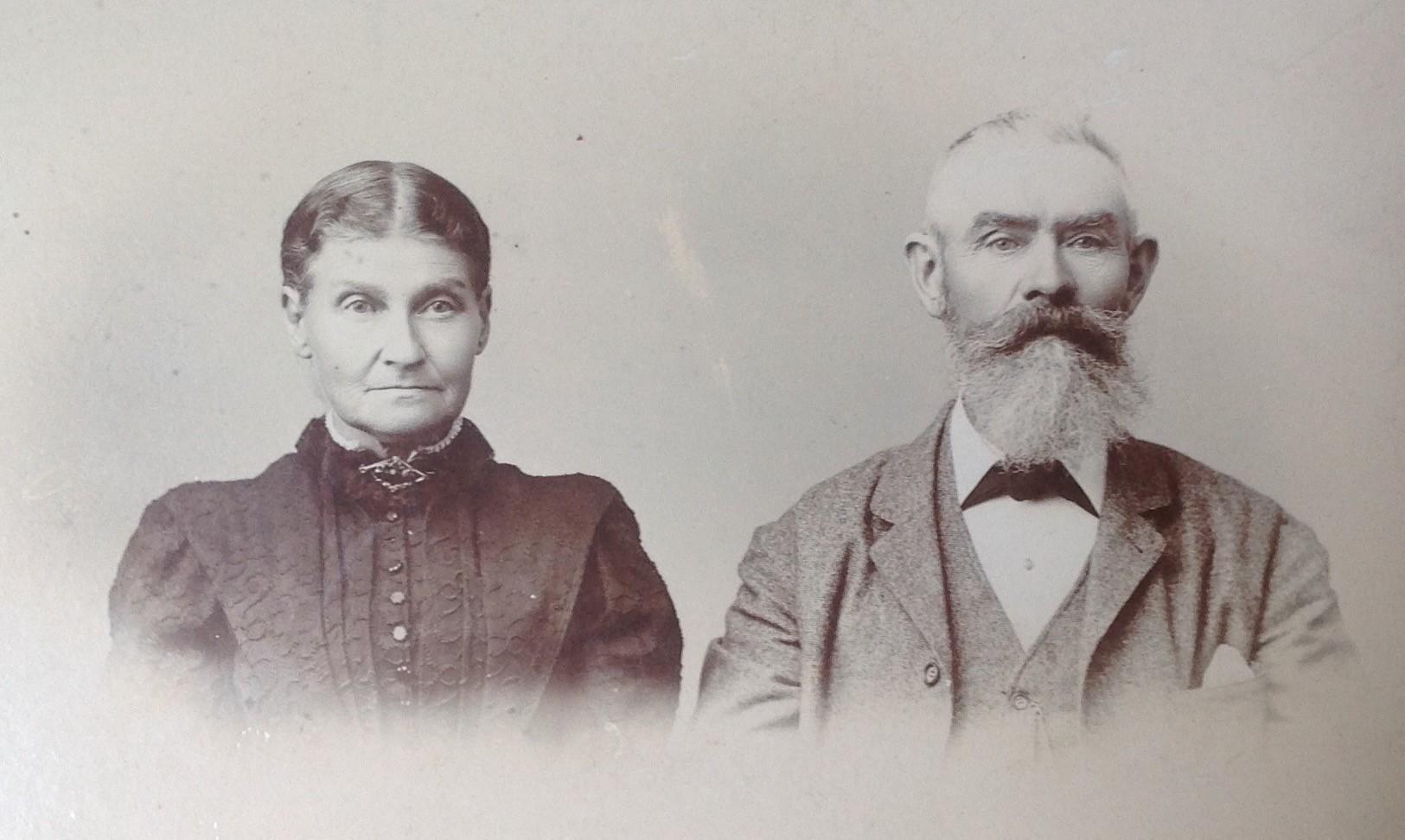

The Cloete couple from Ermelo. Alida Elizabeth Johanna Cloete was born Nel on 6 February 1838 and Hendrik Johannes Cloete was born on 25 September 1834. Alida looks like a jolly old lady. Photograph by Ermelo based photographer C Jullienne.

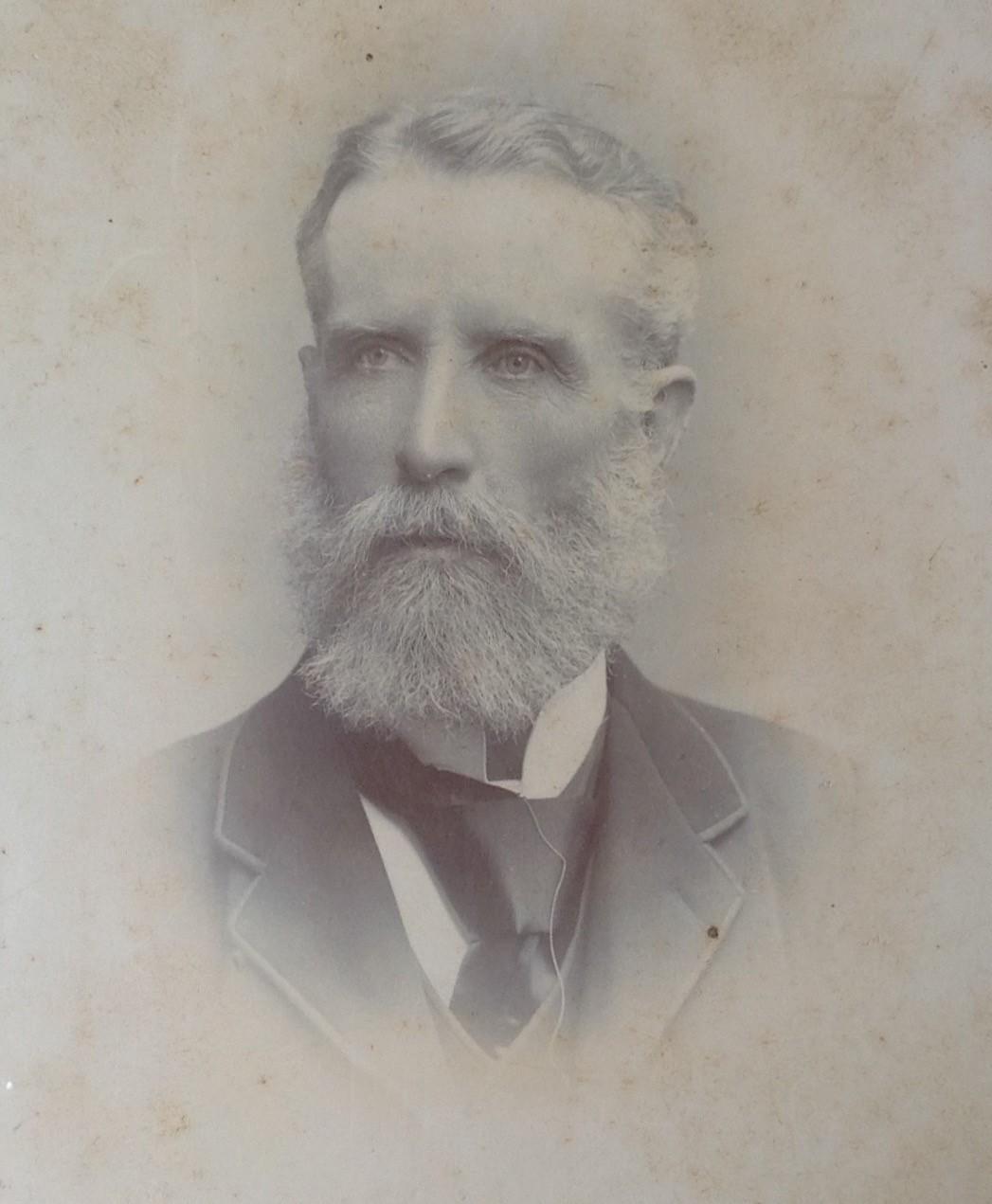

Unknown gentleman by Pietermaritzburg based photographer H Kisch.

South African men and their beards

In previous research on the South African War, researchers significantly mention Boers and their beards. In contrast, the archetypical British soldier was generally clean-shaven.

Several questions arise around our bearded South African men of old:

- was it mainly older men that had beards;

- were beards more prevalent in one province than another; or one culture to another;

- what was the cultural stance (British versus Boer) on the wearing of beards during the Anglo-Boer war period;

- did the bearded man back then also make use of fancy beard oil options;

- did barbers also specialise in the trimming of beards?

Some of the answers to these questions are provided in an extract from Hillegas (2008) below:

The ideal Boer is a man with a bearded face and a flowing moustache, and in order to appear idyllic almost every Boer burgher, who was not thus favoured before war was began, engaged in the peaceful process of growing a beard. Young men who, in times of peace, detested hirsute adornments of the face allowed their beards and moustaches to grow, and after a month or two it was almost impossible to find one burgher who was without a growth of hair on his face. The wearing of a beard was almost equal to a badge of Boer citizenship, and for the time being every Boer was a takhaar (untidy long hair) in appearance if not in fact. The adoption of beards was not so much fancy as it was a matter of discretion. The Boer was aware of the fact that few of the enemy wore beards, and so it was thought quite ingenious for all burghers to wear facial adornments of that kind in order that friend and foe might be distinguished more readily at a distance.

Swart (1998) adds that age was also influential in the early Boer construction of Republican masculinity in that beards became necessary for their dual symbolism of age and manliness.

Older gentleman with an interesting bearded style. Photograph by Durban based WB Sherwood.

Unknown bearded gentleman. Photograph by Jagersfontein based photographer J Ross.

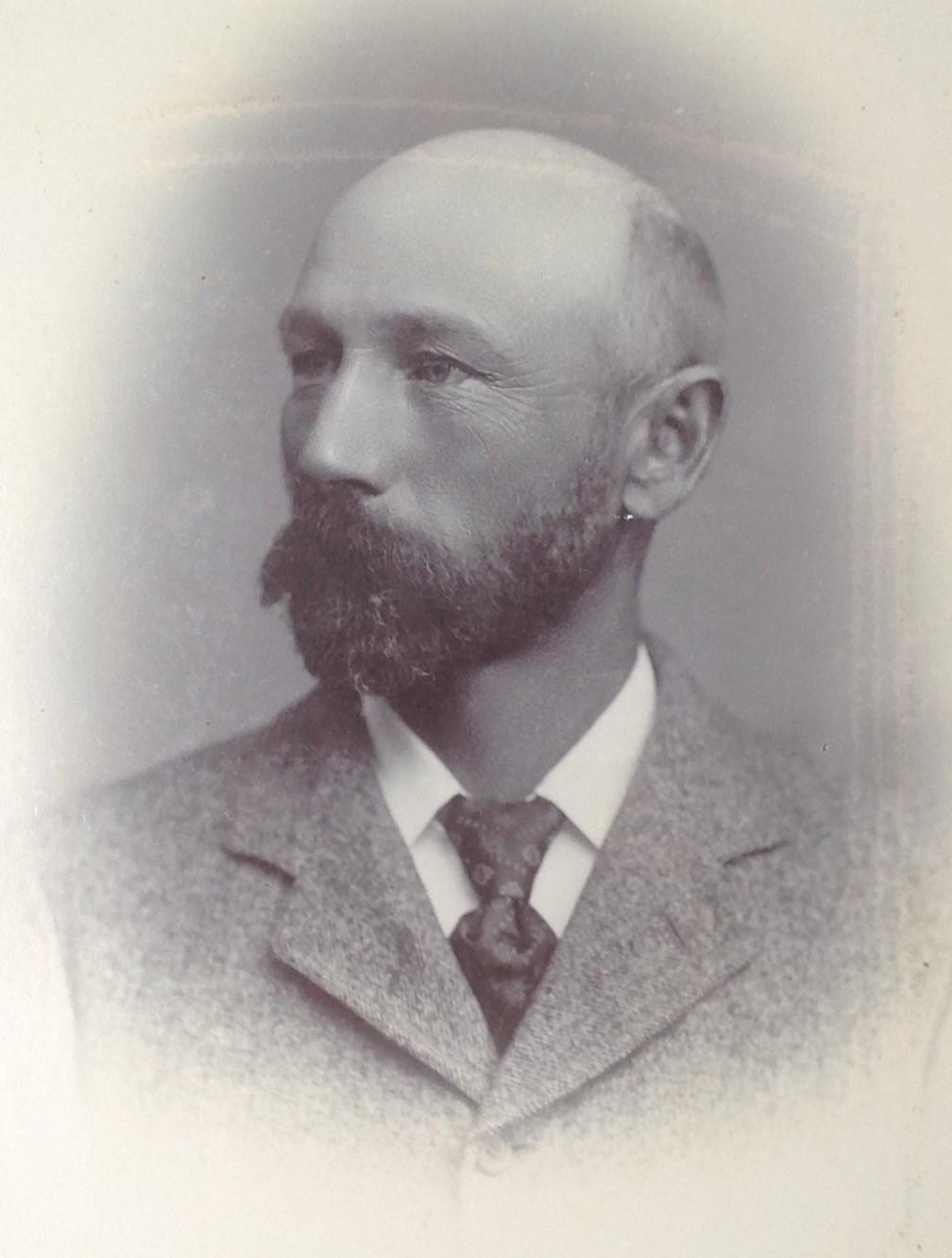

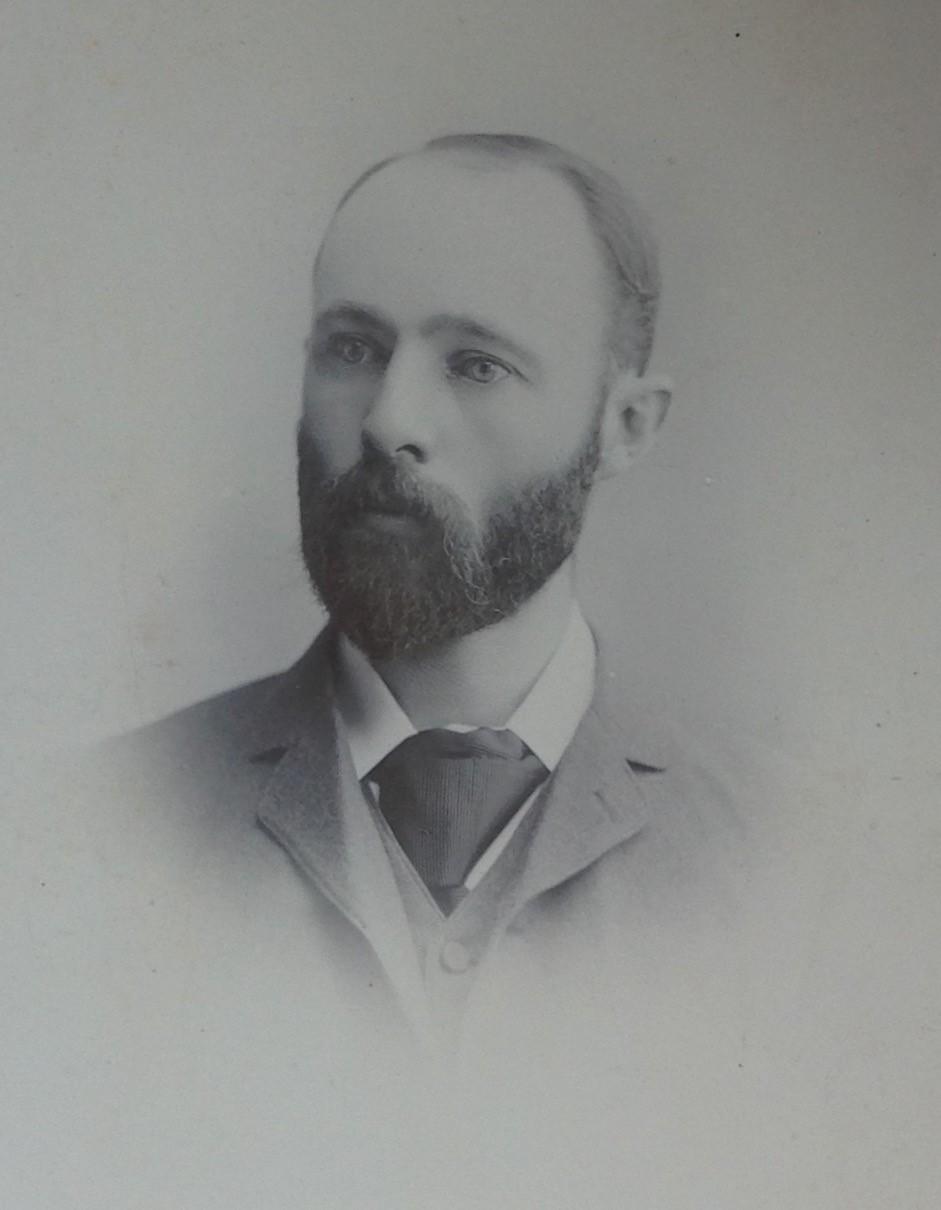

Well maintained beard with a super moustache. Photograph by Johannesburg based Duffus Brothers.

Unknown gentleman by Johannesburg photographer James F Goch.

Unknown couple by Johannesburg based photographer James F Goch

Unknown gentleman with neatly maintained beard. Photograph by Johannesburg based photographer Emil Lewin.

A sophisticated looking gentleman. Photograph by well-known Johannesburg based photographer Horace Nicholls

Germanic looking couple by unknown photographer

Swart (1998) continues by pointing out that with the Defence Act of 1912, facial hair came under the control of the state in which the orders for the army are stated as follows:

The hair of the head will be kept short. The chin and under lip will be shaved but not the upper lip. Whiskers, if worn, will be of moderate length.

This new law affected more than just the soldiers. Military institutions comprised ‘more than uniformed men' - they encompassed the state itself, and their influence permeated society. There was an immediate public response to the new law in that the Act provoked much debate. The English press was for it when The Pretoria News noted that the Act was 'constructive and desirable’.

However, an open letter to Smuts warned that no Englishman would comply with Dutch orders. There was also mild concern that other races were excluded, with a limited degree of concern over the inclusion of lower-class men in regiments because of conscription (Swart, 1998).

One of the post-Rebellion experiences which fuelled nationalist momentum was the humiliation of prison, specifically when the Boer populist, prophet Janse van Rensburg, had his beard forcibly shaven off.

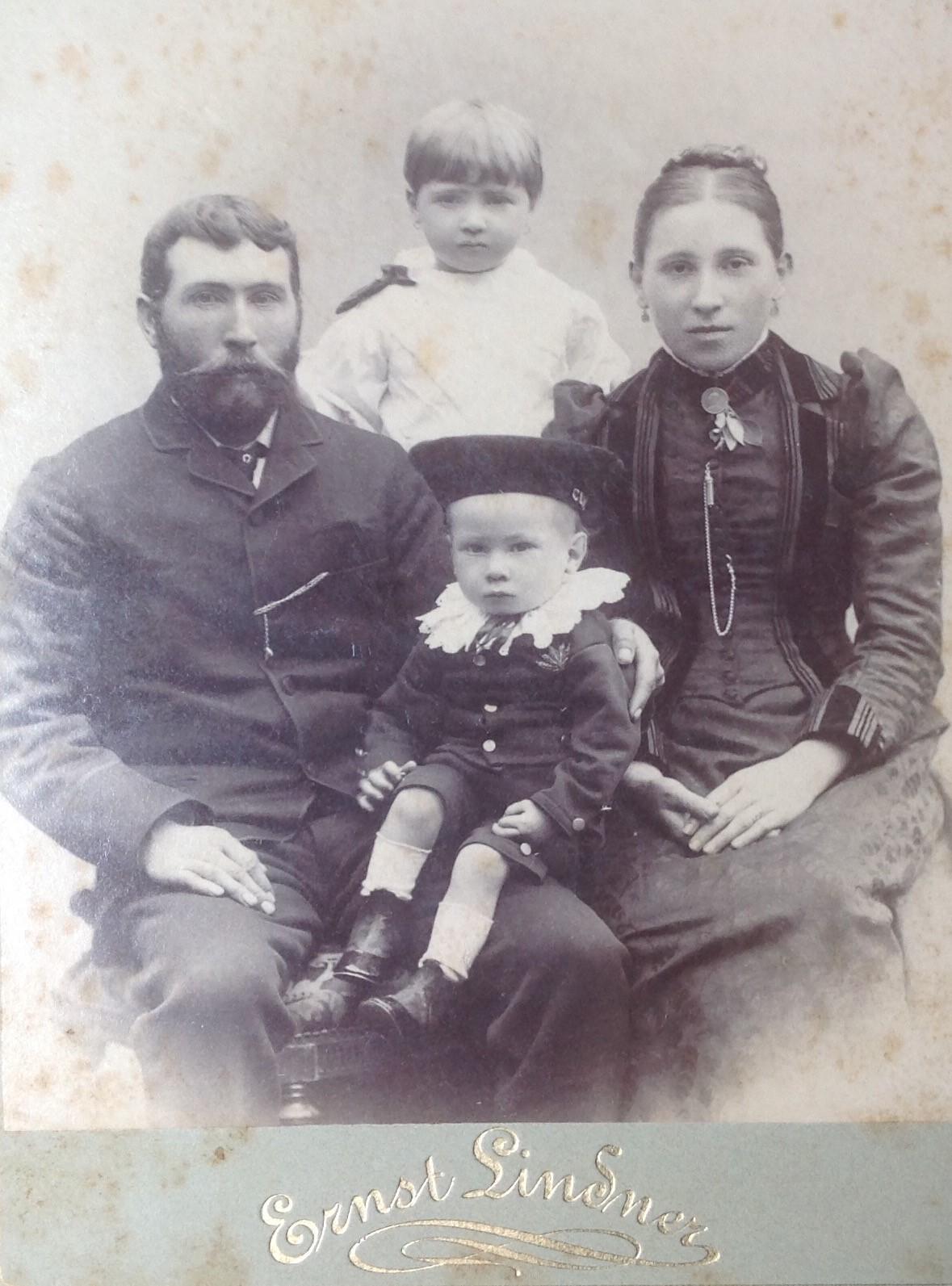

Unknown couple with their children. Note the man’s neatly trimmed beard and moustache. Photograph by King Williamstown based photographer Ernst Lindner.

Young Pretoria based couple. Photograph by Pretoria based photographer HF Gros.

Neatly maintained beard of a Pretoria citizen. Photograph by Pretoria based Munro.

A Pretoria based citizen. Photograph by Pretoria based photographers Plumbe and Bradshaw.

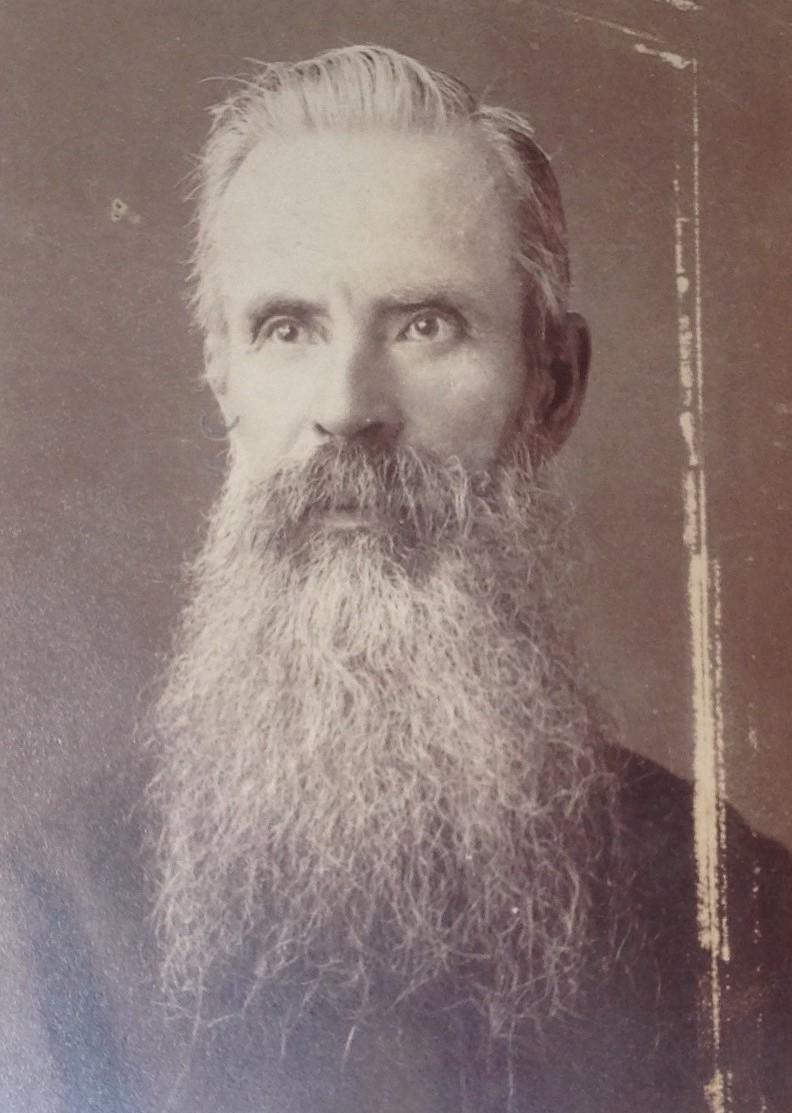

Now that is a serious beard. Photograph by Pretoria based photographer CF Robertson. The line on the right is due to damage caused in the album the photograph was placed in.

Unknown couple. Photograph by S Spangendaal.

Staunch family from Lindley in the Free State. Photograph by The Scholtz Studio.

Now that is a moustache! Photograph of unknown gentleman by Paarl based photographer Gribble.

Unknown gentleman by Johannesburg based photographer James F Goch

Unknown gentleman looking somewhat like a Boer leader. Photograph by Phillippolis based photographer Isaac A Sutherland

Closing

It is interesting to observe modern young men, their beards, and all the beard products available today.

Is there such a thing as “beard envy”?

Here I have to confess, yes, I would not mind having a full-grown beard as we see in some of the Victorian photographs above.

But then, I have to accept the biology behind this all in that genetics is the primary determiner of the rate at which a beard grows and its fullness. Testosterone and DHT (dihydrotestosterone) also play important roles. Beard growth rates vary considerably. There is some evidence that the amount of DHT produced determines a beard's growth rate. DHT is a by-product of testosterone, activated by an enzyme in the hair follicle's oil glands.

To make things more complicated, DHT interacts differently with scalp hair and facial hair. This hormone causes beard hair growth. That means it is possible to have a lush beard and be completely bald on top simultaneously.

There we go; I can blame my parents for not having an optimal beard growth genetic profile.

Older Port Elizabeth based gentleman. Photograph by O Bättenhaussen.

Young man with a rather “modern” hairstyle and impressively manicured beard. Also note his eyebrows. Photograph by Potchefstroom based H Croydon.

The exclusion of other South African races in this article was not intentional but rather because the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC) does not contain images of bearded men of other races. As previously stipulated, photographs of other South African race groups (before 1915) take a lot of work to come by.

Whilst not common in the English language, other words related to beards include pogonophobia (fear of beards), whilst pogonophile relates to the love of beards or bearded persons.

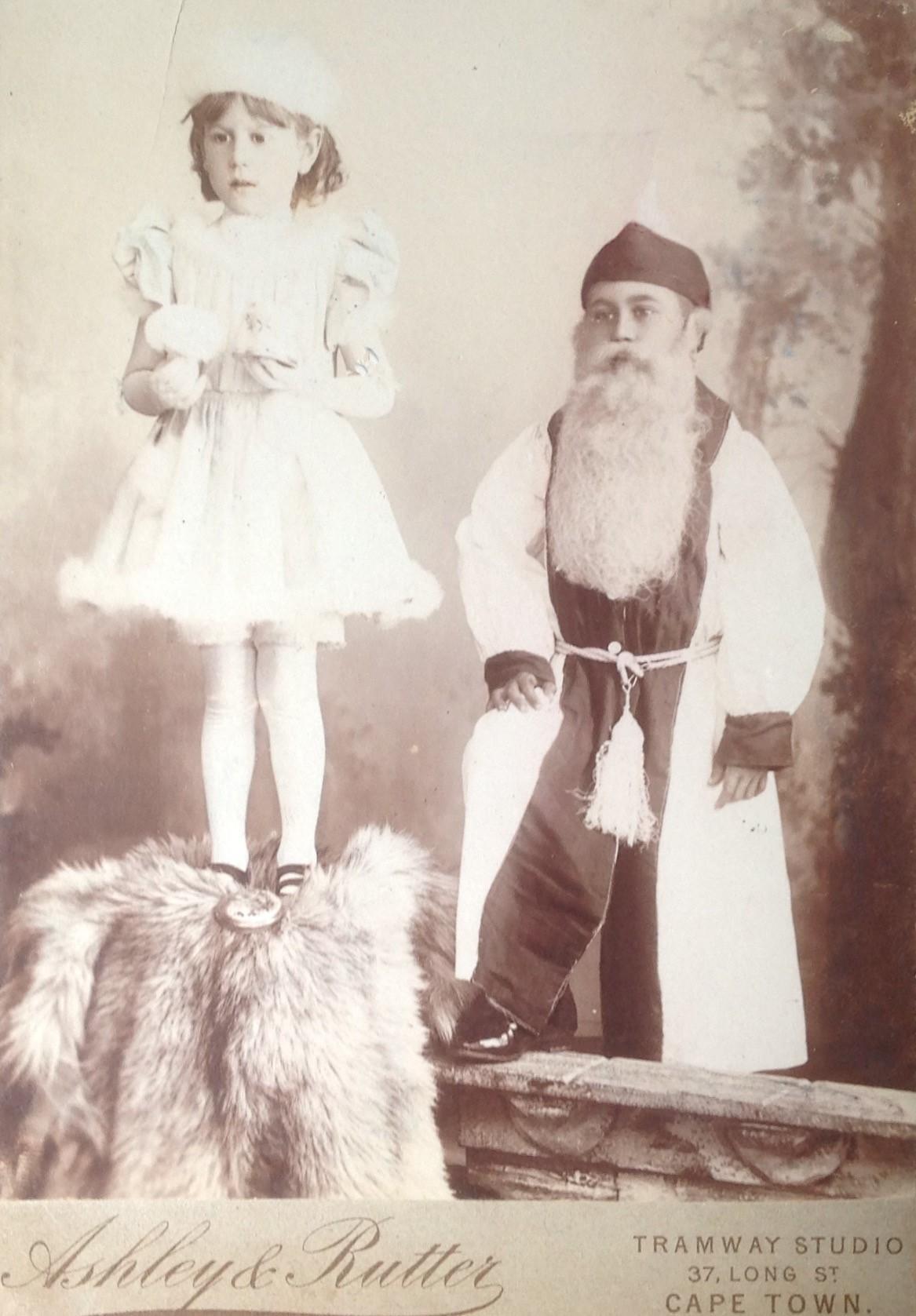

Fake beard and all. Presumably brother and sister. By Cape Town based photographers Ashley and Rutter

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Cull, B. (2014). A Hair-Razing History of the Beard: Facial Hair and Men’s Health from the Crimean War to the First World War (museumofhealthcare.blog)

- Hillegas, H.C. (2008) With the Boer forces – Chapter 3 – Composition of the army. (www.angloboerwar.com/books)

- Meier, A. (2017). Why Victorian Men Had Glorious Beards (hyperallergic.com)

- Swart, S.S. (1998). You were men in war time - The manipulation of gender identity in war and peace. Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 28, Nr 2, 1998. (scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za)

- Unknown (Extracted September 2022). Baarde, baddens, sout - Die mees ongewone belasting in Tsaristiese Rusland en die USSR (www.europeantimes.news)

- Clark, J. & Bryant, C. (2020). Facial hair is biologically useless, so why do humans have it. (www.wired.com/story)

- Unknown (Extracted January 2023). History of the beards – The Victorians. (www.theenglishshavingcompany.com)

- Unknown (2015). Sex object, germ killer, battleground – the wonderful history of the beard (theconversation.com)

- Wikipedia (extracted June 2022). Facial Hair

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.