Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

[Originally published 23 March 2015] The Heritage Association of South Africa (HASA) has noted with great interest the public debate on the matter of colonial-era public memorials and place names – in this particular case those associated with Cecil John Rhodes – for some a great British statesman and industrialist, and for others an imperialist whose colonial and mining labour policies and practices doomed entire generations of black communities – all across the ‘pink’ map of colonial Africa. While commentators have referred to the Rhodes scholarship as evidence of something more benign to his legacy, for others that very same scholarship has its roots in obscene profits made from a now widely despised migrant labour system he helped to engineer. To expect reconciliation between such divergent views and opinions would be foolish.

So let us stress from the outset that HASA believes that such debate is welcome and that it should spur universities across the country to revisit their policies in respect of the role of public culture and heritage. We also reconfirm HASA’s firm belief that heritage, or more specifically the “national estate” – as described in the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA) of 1999 – must serve to reconcile the past, heal divisions and advance the interests of social justice and cultural restitution. Without a broadly shared consensus on how we deal with our troubled past and the monuments and landscapes associated with our deeply painful histories, we will continuously get stuck without seeing a way forward. As HASA we believe that there are useful principles enshrined in our Constitution as well as in the NHRA that may guide us to a more informed decision on what to do during such troubling moments. It is in this respect that we are uncomfortable with some of the public comments made to date.

The NHRA

The NHRA states that public monuments and memorials are part of the national estate and are therefore protected by law. However, this in itself does not mean that the Act is anti-change – and implicitly therefore favours the heritage of one grouping over another. On the contrary, the Act recognises the need for change but envisions informed and managed change so that the concerns (and biases) of the present may not diminish the opportunity of future generations to access the rich, diverse and often deeply troubling and unsettling remains of our material past.

Indeed, we accept that there are precedents for the destruction, removal or relocation of monuments due to development pressures, and even in cases where such monuments are deemed to cause harm or offense to certain communities (not unheard of in post-colonial contexts or in societies that have experienced war, oppression or political turmoil or where there’s a real gender bias in public culture and discourse that needs redress). According to the Act such actions would be permissible as long as the requirements and procedures stipulated in the Act are followed.

Furthermore, guided by the Act, we believe that there are examples of where the removal or relocation of monuments or memorials have been sensitively handled by the relevant authorities. As example we cite the recent relocation of the Barry Hertzog statue at the Union Buildings in Tshwane to a new position in the gardens to accommodate the statue of former state president Nelson Mandela. Whatever one may think of the artistic merit of the Mandela statue, according to all accounts the decision was taken after exhaustive consultation with descendants of the Hertzog family as well as a sound design response that respected the overall context of the gardens. The present therefore opens up into dialogue with the past in a sensitive manner while respecting the historic and cultural context. As a Grade I heritage site such action would not have been considered without prior approval by the South African Heritage Resources Agency.

Mandela Statue at the Union Buildings (The Heritage Portal)

History is not for the sensitive

In light of the Rhodes debacle, HASA would condemn in the strongest possible terms the removal or destruction of public monuments or memorials if such actions do not comply with the spirit and intentions of the Act. We are therefore deeply disturbed by media reports that Dr. Max Price the Vice-Chancellor of UCT was quoted as saying that “the university council was the only body that could make a decision on whether to move the statue.” (ENCA, March 2015, “UCT Vice Chancellor: Cecil Rhodes statue should be moved”). In this, the Vice Chancellor is surely in the wrong, because in terms of Section 34 of the National Heritage Resources Act, no structure older than 60 years may be altered without a permit from the appropriate heritage authority, and in terms of Section 37, are protected in the same manner as places that are entered in the Heritage Register - that is, they may not be changed without a permit.

Secondly, we are rather taken aback that the university did not have a transformation policy and programme in place to deal with its public memorials, spaces and place names – and that it did not secure the support from its student population for such a programme. The UCT's own transformation plan clearly calls for ""making the university a place that is experienced by all its staff and students as being inclusive and nurturing"".

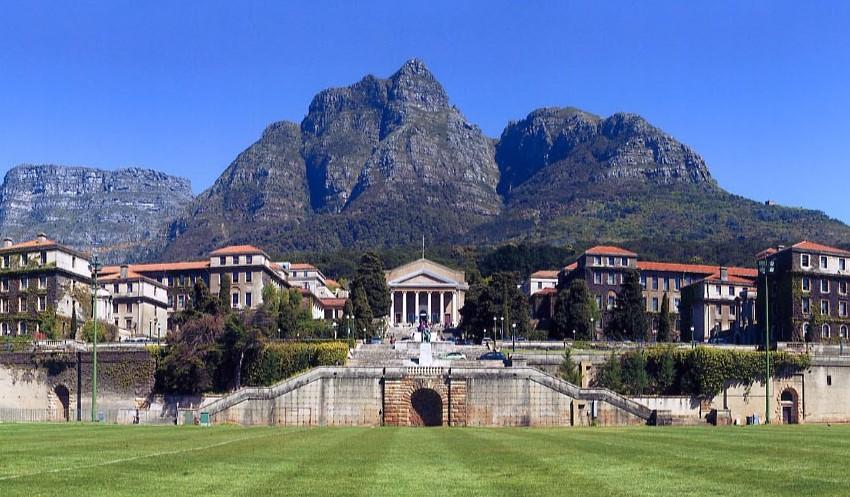

So what happened – or should we ask, didn't happen? One might have reasonably expected that such a programme would've been implemented by now in consultation with students, practitioners and the heritage authorities (the Act actively encourages such proactive measures). If this had been done the university would have had a more coherent response ready in the face of the current turmoil. This is rather ironic given the university’s strong credentials as a progressive leader in the heritage conservation field.

While we cannot second-guess any future decisions made by the authorities on whether the Rhodes statue should be kept in place or relocated (outright destruction would in our opinion be completely against the spirit of the Act and therefore open to legal action), we can refer to internationally accepted practice as well as guiding principles set out in our legislation. Based on this insight we believe that in such cases the better approach would be to create new memorials, public art or interpretative markers that open into dialogue with the Rhodes statue as well as the colonial buildings and structures that are so characteristic of UCT’s upper campus. The layering of the old and the new is a key conservation and urban planning principle – the alternative would surely result in a sterile and sanitised environment. This does also not preclude the option of relocating the statue from its current location to somewhere else on the campus. Either way, the university (including the present students) cannot wish away its colonial roots no matter how hard it may try. Accepting the contested nature of its history – and allowing for multiple interpretations and voices – will in our view be the best option to follow.

If communities are offended by the statue (which we accept may be a completely legitimate view) the university should not attempt to expunge history – this is non-productive and futile, but reassess its policy to ensure that its public space becomes more representative of today’s democratic values. This would be constructive and progressive. That shouldn’t be too difficult given the significant number of black public intellectuals our country – and UCT in particular – have produced.

In our view, this debate is not about the statue but rather the professed lack of transformation at the university. The statue is merely a metaphor for the perceived failure of a system to deliver on commitments made to black students. The removal of the statue is not going to make such complaints go away.

We are equally uncomfortable with proposals that the statue should be moved to a museum as suggested by Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande. The erroneous assumption is that museums are somehow receptacles of an unwanted past - places where we “hide” our skeletons from public view, places that no one visits. This goes against the spirit of the revised draft White Paper for Arts, Culture and Heritage.

Museums play an important role in bringing greater perspective and understanding to our past and it is a national shame that they are left largely ignored by the state that has consistently underinvested in their operations and collections. (We cite the museums under the care of the City of Johannesburg as one such example. Here material objects and artworks of immeasurable wealth and significance to our nation, Africa and the world are left in the hands of a dwindling team of specialists working under the most unimaginably difficult conditions and where the very existence of these collections are at risk.). While museums may certainly serve as a safe haven for cultural artifacts they face their own challenges – in particular how to be more relevant to a democratic and cosmopolitan audience when resources are simply not there to meet their operating requirements, never mind drive new acquisition objectives. Given that there are legitimate complaints that museums’ collections remain untransformed, the last thing curators need are more colonial busts and bronzes. Shifting one heritage challenge to an overburdened museum sector is unhelpful.

Afterthoughts

One of our members recently received a letter from a person (to be clear, a black resident of Mahikeng) – who bemoaned the fact that the bust of Rhodes had been moved from a prominent location in Mahikeng to the Kimberley Club. For him it was part and parcel of the history and identity of Mahikeng and its absence is sorely felt; and according to Prof Howard Phillips (the official historian of UCT) the statue of Cecil John Rhodes has been controversial from the time it was offered to the University in 1931.

A short article by Tanya Farber that appeared in the Sunday times of the 22nd March 2015, suggests that many reasons were advanced at the time for not accepting the gift. Two of these were: “Rhodes was a symbol of English cruelty towards their (Afrikaner) people and the brutality of the Anglo Boer War at the turn of the century” and “An even wider idea:....statues at some point – whoever they are of – would get you into trouble.”

In view of the present circumstances, the idea is profoundly prophetic and is a reminder that history repeats itself.

If the answer is to sanitise history by removing the statue, this will be a mistake because it is tangible evidence of the sad, and even evil path, that the people of South Africa have had to travel in order to reach a better place.

However, should it be decided to expunge the history of Cecil John Rhodes, because we find it reprehensible or not to our liking, then, not only will we be destroying an artifact, we will create a precedent that we may regret when the history of our time is sanitized and the symbols we have created are destroyed.

The Simon van der Stel Foundation, known today as Heritage Association of South Africa, was established in 1959 and is currently the largest and oldest non-governmental (NGO) organisation involved in heritage conservation. For more information visit www.heritagesa.org

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.