Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, Roger Stewart reveals the motivations, passions and dilemma of being a collector. The piece is drawn from the text of the author's presentation to the Owl Club of Cape Town. For more information contact Roger - roger@africanamaps.com or https://www.africanamaps.com.

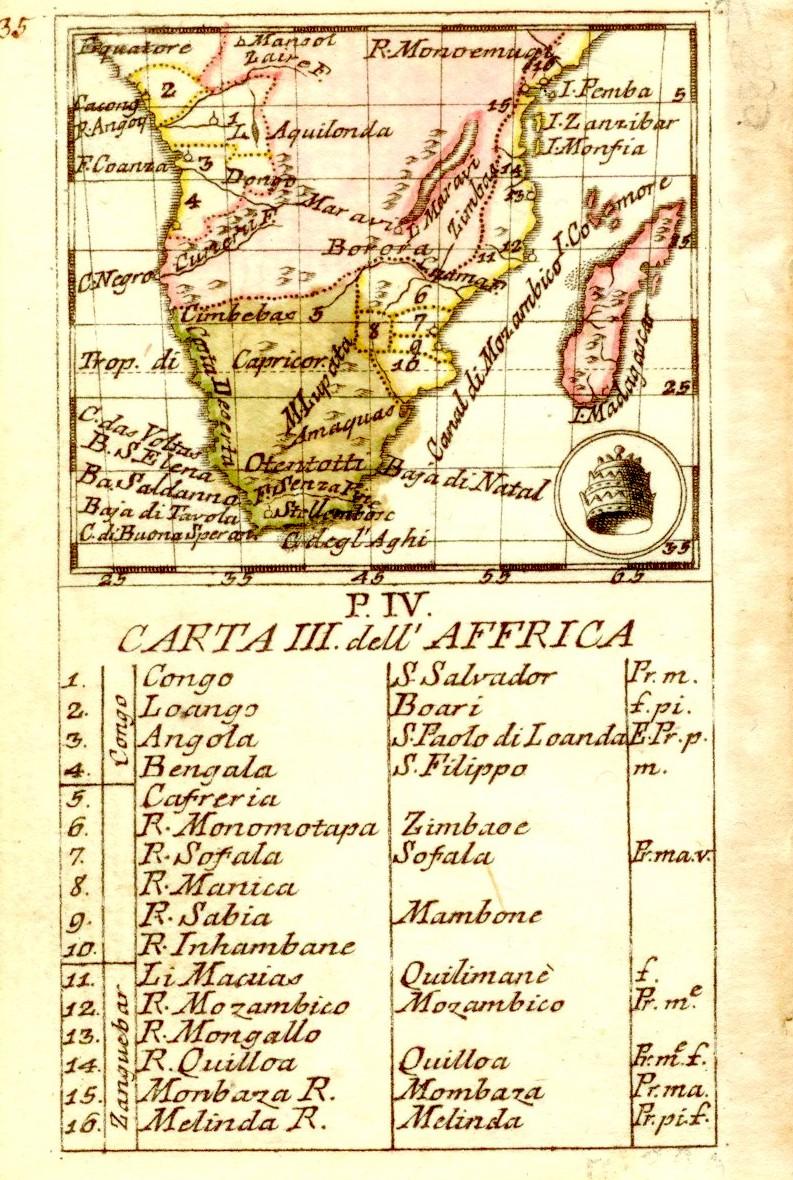

The heritage items I have collected for twenty-five years are printed, antique maps. After a few years of rather chaotic collecting, I decided to focus on a specific category of maps: miniature maps (<150 square cm or <23 square inches) of Southern Africa. Why? Because they made evolving geography knowledge during the age of discovery and colonialism accessible to children and adults in Europe with insufficient means to purchase the very expensive folio atlases. The were also affordable: more expensive per square centimeter but the area was small. They also required technical skill in engraving, printing, and binding. A few even promoted some of the first famous consumer brands. Mindful collecting was my mental salvation during a year of recuperation after a near-death medical experience. However, the decision to focus seems to have precipitated the onset of the aggressive form of collecting.

Within a month of searching, I found a ‘once in a lifetime’ map – the scarce map from the Atlas produced by Aniello Lamberti. I now set my mind on collecting all, from the first printed miniature map until the end of the second Anglo-Boer War. Good luck played a role during my pursuit and so I almost accomplished my goal. A few maps on my ‘must-collect’ list still elude me. Nevertheless, I managed to collect most of the forty-three on my list that now includes small maps (up to double the size of miniature maps). I am sure Michael Blanding will write a sequel to his book, The Map Thief, if I collect the few elusive few maps of Southern Africa that are still on my list.

I found this tiny (5.4 cm x 4.7 cm), once-in-a-lifetime map of Southern Africa in my first year of collecting miniature maps (Aniello Lamberti, 1779)

Collecting need not be just about gathering and hoarding. While collecting, I have spent time learning about the history of maps in the context of social and technological developments over the past four hundred years. I even explored the etymology and the use and the abuse of the words ‘antique’ and ‘antiquarian’. Once I had confirmed the English translations of the Latin antiquus and antiquarius, I concluded that I was becoming an antiquarian who collected antique maps and that I was not an antique who collected antiquarian maps. Sadly, my scholarly treatise on the subject has had negligible impact. I am gratified, however, that only my impertinent grandchildren persist in referring to me as an ‘antique’.

Psychology of Collecting

There are Freudian perspectives on collecting; these are of little concern to the collector but may worry family and friends. Collecting alters one’s personality; detachment from most of society is also a concern – I have been re-assured that this phenomenon is not indicative of a psychotic disorder. Wikipedia has an entry for the Psychology of Collection, but, unfortunately, there is no ICD-10 code for collecting that one submits to one’s medical aid; nor, sadly, is collecting an insurable risk.

Perhaps some collectors will recognize in themselves one or more of my multiple collecting personalities and their attendant behaviors, some of which have owlish features.

- I am a hunter gatherer: patiently but persistently I track down my prey; having found it, immediately I swoop in for the kill, swiftly and silently taking possession of my hapless target. I am sure you will approve of this predatory, owlish behavior.

- I am a hoarder. I take my captured prey to my aerie where I place it neatly in my customised storage cabinets. Every owl should have an aerie for storing his ‘stuff’.

- I am a custodian. I carefully conserve and document the maps and write about them in order to enhance their value. I hope you will approve of this more sagacious, owlish behavior.

- I am an exhibitionist, who seeks out opportunities to display his collection to anyone with an interest and the time to view the exhibits. I apologise for this behavior, which is somewhat eccentric for the taxonomic order to which we all belong.

- I am a raconteur, who willingly speaks about his maps and their stories - with the goal of both informing and, hopefully, entertaining. As befits an owl, I usually offer this somewhat uncharacteristically flamboyant song at night.

Collectors’ Dilemma

The notion of a collection of heritage items as a legacy introduces the tantalising metaphysical possibility of postmortem existence, terrestrial rather than celestial. The legacy issue creates a collector’s dilemma, however. When a collector stops collecting, for whatever reason, should the collection be dissembled and the parts re-introduced into the winds of the collecting environment so that they are disseminated and then collected again, to be re-incarnated with new companions, in new collections and with new stories? Or should they be handed down intact to an heir or an institution?

The lot of most collectors is that heirs do not share any interest in the collection; and, unfortunately, some institutions merely store collections where they languish in a state of indefinite dormancy in the dark, cold recesses of their air-conditioned archives. For example, in the later eighteenth century, when English invasion was a possibility, the VOC’s manuscript maps of the Cape of Good Hope were sent into protective hiding by Governor De Graaf from the Cape to the Netherlands. They were so well hidden, from both the English and the Dutch, that they languished in Delft’s archives for more than one and a half centuries – until they were discovered by chance in 1950.

Collecting and Civilisation

Recent heritage tragedies lead me to a more serious perspective on collecting. The philosopher and author, George Santayana suggested that those who forget the past are likely to repeat it. Collections of any kind have the potential to remind us of the past, but, while remembering might be necessary, it is not sufficient for avoiding repetition of the past. For social progress we also need to learn from the past: learn in a way that changes for the better our way of thinking and our values, which can lead us to behaviors that advance our civilisation. I suggest, therefore, that well documented and presented collections, which tell stories of the past, good and bad stories, are valuable assets that epitomise civilised societies: in a nutshell, conserved, curated collections create cultural capital.

Civilised societies nurture collectors and collections, even collections from or of terrible or currently unpopular periods of history. The €375m and ten years of transforming the building and presentation of collections at the Rijksmuseum is a recent example of a nation’s patient understanding of and commitment to the cultural value of its collections. The 2.5 million visitors in the year of re-opening of the Rijks, and 10% more the following year, attest to the national and international appreciation of the collection’s cultural value.

South facade of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam (Wikipedia)

The period of damnatio memoriae in ancient Greece is surely not to be repeated when it comes to collectors and collectible objects which become unpopular. However, recently we have witnessed the tragic loss of cultural capital. The wanton destruction of Palmyra, one member of Syria’s collection of ancient city ruins, is an example. Collections have also been lost through neglect, such as the destruction by fire of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro; or most recently, as many of us witnessed on TV, the extensive, accidental damage to Notre Dame, one member of France’s collection of beautiful old cathedrals. This last-mentioned tragedy resulted in the outpouring of private financial capital to restore cultural capital for all of society. Surely, we can learn from the tragedies and from the foresight and commitment that led to the success of the Rijksmuseum. The condition and funding of numerous South African institutions with heritage collections is a cause for concern, but is there a political or public will to conserve and curate their inheritance … and learn from them?

William Burchell, the English naturalist, and philosopher, who trekked in an ox wagon through South Africa (1811-1815), commented with sagacity on collecting. The context of his comments was the field of natural history, but his sentiment is universally applicable:

... he who extends his view (of collections) beyond the narrow field of nomenclature, beholds a boundless expanse, the exploring of which is worthy of the philosopher, and of the best talents of a reasonable being ...

To return to maps, a quotation from Italo Calvino’s book, Collection of Sand, resonates with me. ‘The geographical map ... although static, implies a narrative; it is ... an Odyssey.” Since I started collecting antique maps, I have been on numerous odysseys; I have attempted and will continue to try to create some cultural capital from map collecting, mine and others, such as the recently resurfaced Schrire Africana Map Collection.

To be quite candid, collecting is also aesthetically pleasing: the sheer enjoyment of collecting and learning has been sufficient reason for collecting my small pieces of otherwise now-useless old paper.

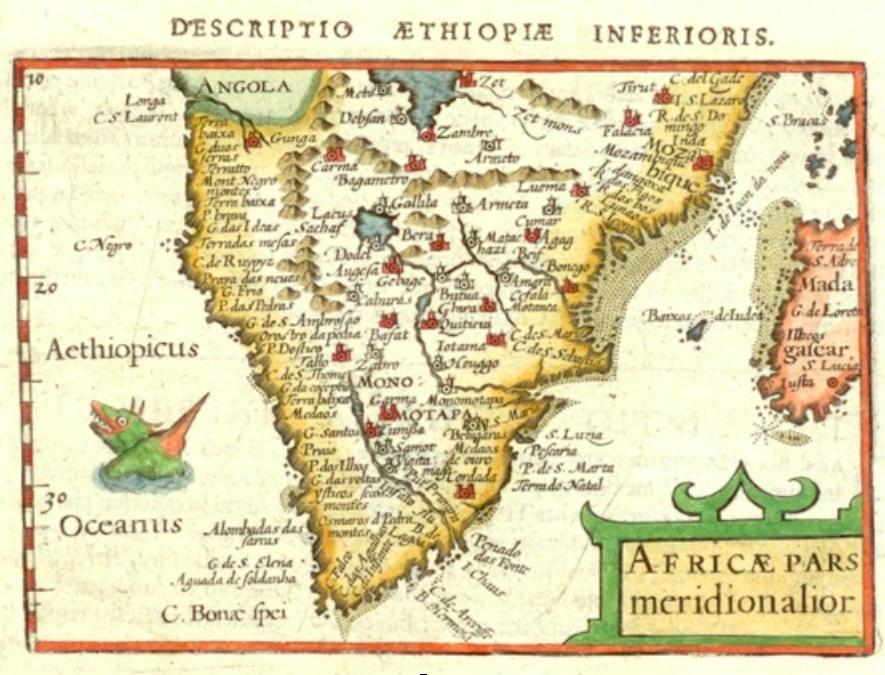

I now retain only the various editions of this, the first miniature map of southern Africa; here the 1603 Latin edition.

P.S. My approach to the collector’s dilemma: My collections of miniatures (one of South Africa and one of Africa, the entire continent) were sold, together with detailed cartobibliographies, to institutions, one in the USA and one in the RSA. Nearly all the other maps I collected have been distributed into the winds of the wider collecting environment in the hope they will find new companions, collectors, and cultural meaning.

A final confession: I continue to hold only one set of miniature maps – all editions of the first printed miniature map of South Africa – I am still on the lookout for one elusive edition of he map.

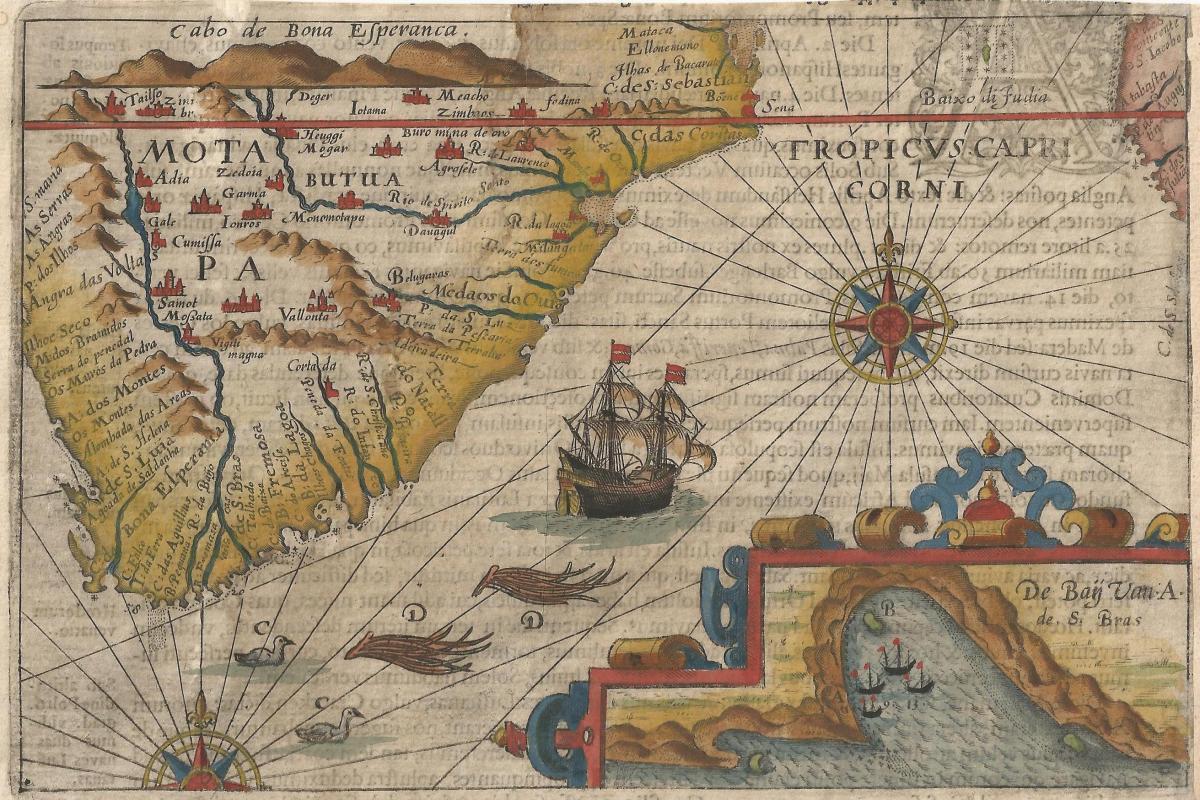

Main image: The VOC did not produce any miniature maps, but his small map (21.3 cm x 14.1 cm) came from the 1598 journal of Willem Lodewijcksz who was the diarist on the first VOC voyage to the East Indies (Amsterdam: C. Claess, 1598)

For more information contact Roger - roger@africanamaps.com or https://www.africanamaps.com/

Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals. Roger represents the International Map Collectors’ Society in South Africa, and is chairman of the Bibliophiles in Cape Town, and of the Friends of the Cape Medical Museum.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.