Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

If you wish to depart this earth in a puff of smoke, Johannesburg has just the place for you. It has an excellent state of the art crematorium that has kept up with the times. Here is a heritage building with a difference. I have known about the crematorium since I was a child and attended a cremation service for the father of a friend. I have always found cremation ceremonies to be harrowing in the extreme because the visible observation of human remains going up in smoke is just too graphic and disturbing and seems to make the finality of death and farewell so totally final. Of course, my attitude is completely irrational but being buried seems so much more natural than a dramatic conflagration. The rational part of my brain stayed with the idea that a cremation is efficient, clinical and environmentally sound.

Cremations are not as popular as burials but their social acceptability has been rising. The convenience of a cremation is that you ultimately receive the ashes of your loved one and those ashes can be scattered wherever the mourning survivor wishes.

Crematorium in the process of expansion with the addition of an extension on the right hand side (SA Builder Magazine)

A more recent photo of the crematorium (Kathy Munro)

Alan Buff, the man in charge of Johannesburg’s cemeteries, explains the details of cremation in a note from 2011: “Bodies consist of 80% water, so in cremation there are only bones left after the burn is finished. These are put through the granulator, which crushes the bones to powder. These remains weigh about three to five kgs. Usually only a portion of the ashes are given to the family, the rest get placed in a pit in Braamfontein cemetery.” (File note in the JHF Resource Centre)

My mother wanted to be buried and so she was in West Park cemetery, but my father opted for cremation and I made the journey to England with a sealed canister of his ashes given to me by Hobkirks for scattering on his childhood haunts on Cleeve Hill above Cheltenham. We sobbed an ocean of tears over my mother’s grave but for my father, we walked Cleeve Hill on a glorious slightly breezy English summer day, and went for a family lunch at the Rising Sun with my Dad’s English relatives funded by £180 I had found in the pocket of a tweed jacket. It was a celebration of an interesting life and a wonderful man. There were no tears but laughter when the wind blew some of the ash back into our faces on the hillside. In fact it was all pure Goon show comedy, which my Dad would have loved. We all remembered my Dad and enjoyed a laugh. That was the day I decided that cremation had a lot going for it.

Cremation as a process that consumes the remains by fire is a very elemental thing. We do move from “ashes to ashes and dust to dust“. So a crematorium has a state of the art furnace. The point of a cremation is to dispose of the human remains by fire speedily, cleanly and efficiently. The 1930s booklet explains: “During the process of incineration the body is never in actual contact with the fire - a low wall separates the incinerating chamber from the fire. The body is consumed amidst the incandescent gases emanating from the furnace.” It was directed that the coffin be made of some readily combustible wood, such as deal, white pine or three ply wood, and it was advised that metal nails must not be used.

The interior of the crematorium in the early 1930s. Note the extension eastward of the Crematorium, within two years of its opening. (SA Builder Magazine)

There is a columbarium or crypt at the Braamfontein cemetery where it is possible to choose a resting place for an urn of ashes. A few years ago I encountered the story of Frank Wild (1873-1939) the polar explorer and second in command to Shackleton, whose ashes were found by his impassioned biographer, Angie Butler. His remains had been forgotten in the Braamfontein Columbarium (although Wild had been given a civic funeral and cremation of note). Butler was able to retrieve Wild’s ashes and take them for reinterment next to Shackleton on the South Atlantic island of South Georgia (click here to view a YouTube video). That is the point of a crematorium, if you are cremated you can choose the final home for your remains.

Book Cover

Johannesburg of the 1930s was a progressive city and in 1931 the decision was taken to erect a crematorium at the Braamfontein Cemetery. Cremations were a relatively new and novel way of dealing with death, and whilst not nearly as acceptable as burials, they offered an environmentally compatible method of disposing of human remains, catering for a diversity of religions and at the same time economized on urban land. The Hindu crematorium in line with Hindu religious practice has been a feature of Johannesburg’s infrastructure since 1918 and it had been Gandhi who had first campaigned for land to be set aside for this use.

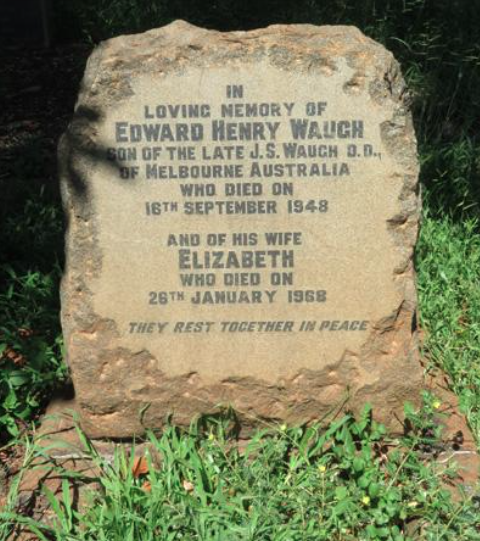

The Braamfontein Crematorium is a facility that has served the Johannesburg community, together with the Hindu crematorium, for well over eighty years. It has a surprising location on Graf Street, alongside the motorway and is accessible through a gate that leads into the oldest extant Johannesburg cemetery, Braamfontein Cemetery. It was built in 1931-32 and opened in 1932. It cost £9,000 and was designed by E H Waugh, the Johannesburg City Engineer, whose work is commemorated in a plaque at the Crematorium.

Plaque commemorating E H Waugh (Sarah Welham)

Waugh (1872-1948) was one of a remarkably talented series of City Engineers and Johannesburg owes much to that fine cadre of men, such as Andrews, Waugh and Hamlin. Waugh was an Australian and was both an architect and an engineer. He arrived in South Africa in 1898 and first worked as a surveyor for the Cape Town Corporation, but did not remain for long as the next year he left for England to study architecture at King's College. He returned to South Africa to serve with the Rand Rifles in the Boer War and then remained in Johannesburg where he was employed as a building surveyor and became chief of the architectural branch. Waugh was responsible for the supervision of the building of the Johannesburg Market Building in Newtown and for the municipal abattoir.

Market Building Newtown nearing completion in 1912 (Museum Africa)

Waugh also supervised the building of district fire stations for example the Dolls House Fire station in Berea. He had a keen interest in the architectural profession and in 1912 was elected an Associate Member of the RIBA. Waugh succeeded G Burt Andrews as Town Engineer in 1927 and became City Engineer from 1928 until his retirement in 1932. He continued to work for the promotion of architects’ interests and to undertake professional work after his retirement. Waugh died in Johannesburg in 1948 and was buried at West Park Cemetery, which is ironic for the man who designed our crematorium. Waugh Avenue in Northcliff, Johannesburg is named after him. He was a remarkable man. (Information sourced from Artefacts)

Waugh's Gravestone (Sarah Welham via Artefacts)

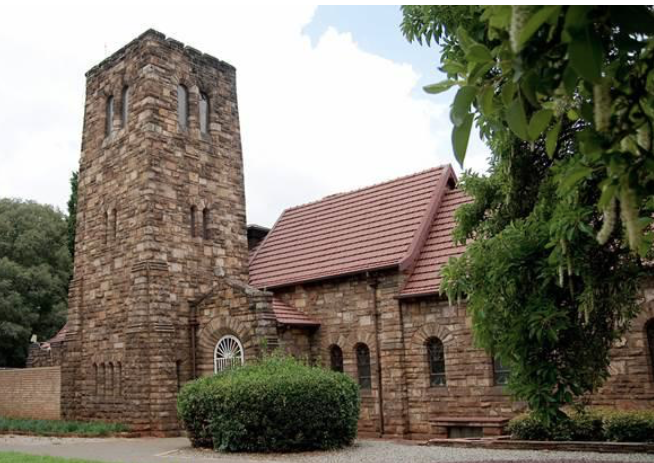

The design of the crematorium almost disguises its purpose. It is in the shape of what van der Waal calls a “neo-Romanesque” chapel built of cut Witwatersrand koppie stone. It resembles a church with neat small single, double and triple arches, a hip tiled roof and most imposing of all is a substantial square rather heavy tower (but on closer inspection it is not a bell tower but rather a chimney for the cremation furnaces). An undated (probably 1930s) pamphlet about the crematorium (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation resource centre pamphlet collection) describes the building as comprising “a chapel, chancel, organ chamber and spacious porch-way built of local stone in the Byzantine style, but it goes on to add that “all appliances for modern cremation have been installed“.

The first ever cremation was for a Calvert J Wakeford who died on 28th February 1932 aged 60 years old. He was cremated on 1st March 1932. The second cremation was a Morris George Prosser who died aged 51 in Boksburg on 1 March 1932 and was cremated a day later. The City Parks brochure on its Parks and Cemeteries reports that: “The demand for cremations was greater than could be met by a single furnace and it was proposed to provide for an additional furnace.” The crematorium was expanded in 1934, hence the photographs from the S A Builder Magazine.

By 1942 there were 6 603 burials in the four cemeteries under the City Department’s control, 641 cremations in the Braamfontein Crematorium and 25 at the Hindu Crematorium in Brixton. Roughly cremations represented only 10 per cent relative to burials. The idea of a memorial wall was introduced in 1934. The book on Johannesburg that showed the city at its promotional best was The Golden City (edited by Alistair Macmillan). It has no date but was probably published circa 1934 (it shows a picture of the Crematorium on pg 248). Clearly the idea of agreeing to cremation was something Johannesburg citizens were just getting acclimatized to. By 1950 the former Prime Minister Jan Smuts’s funeral was held in Pretoria; he was given a massive state funeral with all well deserved honours but he was cremated in Braamfontein and his ashes were scattered on the koppie above Doornkloof (his farm at Irene). There is a silent Pathe news clip of the Smuts funeral viewable on You Tube (click here to view). Cremation was no longer such a novelty..

The crematorium with four new furnaces installed in 2011 (Sarah Welham)

Four new chimney stacks giving the traditional chapel an industrial look (Sarah Welham)

How do charges for cremation compare to charges for burial? The fee for cremation is quite modest. The tariff of the City of Johannesburg for 2016-7 was R952 for a standard cremation, but R1231 for a large body, i.e. over 120 kgs and the use of a chapel per 60 minutes was R500.

Thank you to Sarah Welham and the team from the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation's research centre for their assistance with this article.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.