Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The ice-cream cart or tricycle is not a new idea and goes back to the 1920s and to Mr Wall and Sons of London. They owned a butcher’s shop but the pies they made were only popular in winter. They got the idea to make ice-cream to use factory capacity during the summer months so they didn’t have to lay off workers when no-one wanted to eat hot pies. The First World War got in the way of their aspirations, but when finally launched Wall’s ice-cream, sold from ice-cream carts, the product was an instant success. At first, the ice-cream vendors made their way through the streets of London with horses and carts and then Walls’s developed their famous ‘Stop Me and Buy One’ tricycles. The number of Wall’s tricycles on the road increased from 10 in 1922 to 8 500 in 1939. Even now, replica Wall’s bicycles can be seen in tourist towns and beachfronts in the UK.

Replica ‘Stop Me and Buy One’ Wall's ice-cream tricycle team in Britain (The Mail on Sunday newspaper, 10.03.1985)

Ice-cream consumed in great quantities around the world

Europeans buy and eat, on average, about 9 kg of ice-cream each per year. In fact, the ice-cream demand is so great in Europe that the ice-cream industry produces more than 870 million gallons of ice-cream every year, generating around $5 billion in revenue each year. Even during the Covid-19 lockdown in the UK, the public were still flocking to the beachfront to buy ice-cream at kiosks and carts and ignoring social distancing. In the US, Time magazine reports that July is the time of year where the most ice-cream is consumed (it is their summer) and that there has been a huge surge of luxury and creative flavours onto the market (Rosemary and Black Peppercorn flavoured ice-cream). South Africans consume almost 60 million kilograms of ice-cream a year according to Euromonitor’s market research (about 1 kg each).

Interestingly, there are some downsides to the street sales of ice-cream. In 1998, the US state of New Jersey passed an ordinance that banned amplified and mechanical music from ice-cream trucks as this was considered a nuisance. New York did the same in 2005. This is something we might want to consider in South Africa – or perhaps we still enjoy the jangled cry heralding the arrival of an ice-cream van on a hot Highveld afternoon!

Those ice-cream bicycles at South Africa’s parks and beaches

After the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown that familiar sound of the ice-cream man’s tinkling bell at Zoo Lake reminded me suddenly of childhood outings to Zoo Lake and how fascinated my brother and I were by the smouldering block of dry ice at inside the ice-cream cart. Of course we knew not to get our tongues stuck to the ice-creams and waited a few minutes before taking our first licks.

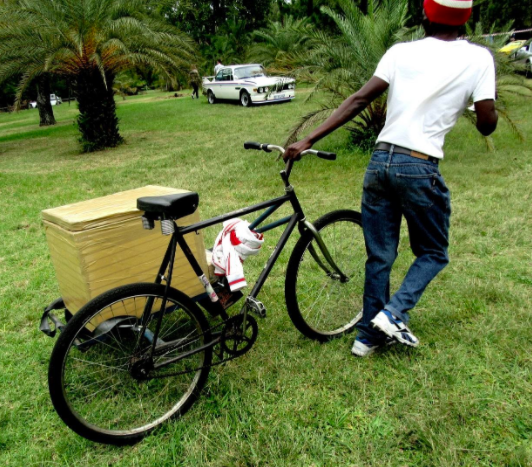

Those ice-cream men are still around, selling ice-creams at Zoo Lake, Emmarentia Dam and at events like Angela’s Picnic, an annual show of vintage cars at Delta Park. They also arrive at school gates just in time for the final bell and the flood of children surging out to meet parents. School kids can still buy a frozen ice lolly from these guys for less than five rand. These lone ice-cream vendors are a well-known, but largely unrecognised part of the urban landscape of Johannesburg. Some of the ice-cream vendors I spoke to were clearly unhappy about the small amount of money they made for such a lot of physical work. Yet, the one-man ice-cream bicycles have been around for very many decades.

Ice-cream vendor at Angela's Picnic car show, Delta Park, 2017

Efforts to regulate informal street trade in Johannesburg

Around the world, rapid urbanisation has created a situation where urban economies have been unable to match the increase in the urban population with employment opportunities. Growing numbers of the urban poor eke out a marginal existence in the informal sector as street traders. Jessica Arias (2019) found that in the year 2007, there were an estimated one million street traders in all of South Africa’s cities, with over 70% selling food. Street traders contribute greatly to the overall economy of South Africa, she found, selling freshly cooked foods, fresh produce, packaged food, and other products and rendering services such as shoe shining and cutting and braiding hair.

Informal street trade in the Johannesburg city centre (Sue Taylor)

The Business Act No. 71 of 1991 of South Africa sought to get to grips with informal trade through removing a range of rules and regulations which had hampered and harassed informal traders. In 1995 the new national government put out the White Paper on Small Business which set out South Africa’s new thinking about small, medium and micro enterprises. The 1995 South African White Paper intended to promote the principles of support and inclusion for the informal sector in South African cities is still not right.

Clair Bénit-Gbaffou (2015) explains that there are complex debates about informal trade and the right of traders to occupy public space in South African cities. Because of the conflict and evictions they face, most street traders in the Johannesburg city centre have organised themselves into associations. Bénit-Gbaffou also explains that in recent times, the City of Johannesburg has invested heavily in formalising street trade, putting stalls in certain areas of the city centre, yet there are always tensions between the city and both illegal and legal traders. The notorious Operation Clean Sweep in 2013 saw street traders in Johannesburg, whether legal or illegal, literally swept away (Arias 2019) and clearly showed that the city could make not up its mind which sector of the urban economy to support - formal shops and businesses or informal trade. In the same way, in the lead up to the 2010 World Cup Soccer event, the City of Johannesburg made several brutal attempts to eliminate ‘visible forms of poverty’ like street trading. This reflected an on-going prioritization of international investment and tourism over the survival of people who live and work in the city. This negative stance against street vendors also contradicts the City of Johannesburg’s efforts to market itself as a World Class City, not realising that the factors that make many international cities so fascinating are the street foods, curio markets and fashion districts.

Some Johannesburg vendors choose a free-wheeling life

Perhaps all the conflict, violence and uncertainty about pavement trade in the inner city is why some persons choose to operate as individual mobile ice-cream vendors, always cycling to distant parks and school gates. As noted by the ice-cream vendors outside our local school gates, a new vendor would occasionally seek to set up some distance down the street, hoping to attract customers. There would be shouting and after a few days, the newcomer would not be seen again. Even the humble trading turf outside a school gate which allows for only about an hour of trade per day after the midday school bell rings and after a sporting event, is worth fighting for.

A quick scan of academic studies of informal street trading in South Africa found that ice-cream vendors are never included as bone fide street vendors or micro-entrepreneurs. There are literally no studies on their activities. Other forms of vegetables and fruit selling, cooked food selling, as well as selling cut flowers and other goods in the city streets, have been extensively studied. One recent study done in the Western Cape showed that street vendors selling cooked meat, boiled eggs, cupcakes and so on, can make a profit of around R1000 per month.

Although ice-cream vendors form part of Johannesburg’s informal street traders, they always seem to be alone. Clearly, they need to get organised and find a way to improve their businesses and profits.

A lone ice-cream seller at Zoo Lake, Johannesburg, in the 1980s.

Where do the ice-cream vendors get their ice-creams?

In South Africa, many of the ice-cream vendors are young men, while others are much older. This trade seems too arduous for women. These vendors are incredibly hard-working and resilient. They represent the brave efforts of individuals to earn an income and not become part of the millions of people out of work in South Africa. They are not allowed to trade in public parks, as per municipal bylaws, and over all the past decades they apparently never had trade permits but no-one actually noticed or complained. The question is, how does this system work and where do the ice-cream sellers in Johannesburg get their bicycle carts and the ice-creams? How far do they have to peddle those heavy bicycles to arrive at Zoo Lake or Emmarentia Dam in time for the weekend? And do they make enough money to make it all worthwhile? I made some effort to find out where these men get the ice-creams and the tricycle carts and whether there was a system for this.

Emmarentia Dam (The Heritage Portal)

In the past there apparently used to be a distribution centre in ‘Newtown’ that supplied the bicycles and ice-cream. I haven’t been able to find information on such a place. However, one of the vendors I spoke to recently said he gets his cart and ice-cream stock in Booysens. I checked and found Mr Tasty’s in Mentz Street, Booysens. Mr Tasty’s was helpful, but all they could tell me was that the vendors just buy ice-cream products from their shop and they already have their bicycle carts. I started working out distances. An ice-cream vendor would have to peddle the heavily laden bike from Booysens to Zoo Lake via the back roads (i.e. not on the motorway!), a distance of about 10 km and the same distance back again, all to be done within a single day. The bike has to be back at the depot each evening, my informant said. I drove to Mr Tasty’s and found that there were some really nasty, congested streets with large trucks and that riding a clumsy bicycle on these roads would be rather horrifying. Also, although I went on a Friday afternoon, I didn’t actually see squadrons of ice-cream carts heading out in formation towards the northern suburbs and their parks. It would take two hours and 7 minutes to walk this distance of 10.5 km, obviously quicker on a bicycle, although those creaking old ice-cream tricycles are not built for efficient travel. Some of the other vendors told me they buy their ice-creams from Gatti’s in Fordsburg. Gatti’s said the vendors purchase the ice-cream from them and have been doing so for 30 years, but that they own their own bicycles. However, the three ice-cream vendors that I spoke to said they get both the ice-cream and carts from the various ice-cream wholesalers, so this is all a bit murky. Seems like there must be middle men involved who rent out the carts to the ice-cream vendors.

Efforts to create small ice-cream businesses in South Africa

Cashing in on the enduring popularity of ice-cream, in 2006 Nestlé South Africa started an Ice-cream on Wheels initiative amongst unemployed youth, aimed at job creation and skills development. There have been problems with this initiative though. As already mentioned, many South African city by-laws restrict street vending and the highly visible Nestlé ice-cream carts did not pass unnoticed. Nestlé did manage to reach agreements with some coastal cities to allow the vendors to trade in beachfront areas.

The main goal of the Ice-Cream-On-Wheels project was to help young people get involved in the business of selling Nestlé ice-cream. Nestlé SA gives participants R1 500 worth of initial stock to sell. The profits from the stock are used to buy more stock from Nestlé SA. In addition, in collaboration with government’s Umsobomvu Youth Fund, Nestlé provided vendors with motorcycles or bicycles and uniforms. Vendors also receive training on how to run their businesses. Since 2006, 1 300 of the Nestlé street vendors started operating in Gauteng and Durban. One still sees these Nestlé vendors at parks and events, so the initiative must still be running.

Nestlé ice-cream cart at the Johannesburg Botanical Gardens (Emmarentia Dam)

The business of selling ice-cream from carts

A quick look online reveals any number of small mobile vehicles from which to sell ice-creams. Although the traditional style ice-cream tricycle remains a favourite, there are literally hundreds of other types of vehicles to choose from across the world, from the motorbike version of the tricycle often driven by women, to ice-cream trucks and vans. In the USA and UK, modern ice-cream carts can be very sophisticated. For example, contemporary ice-cream carts no longer need that block of dry ice to keep the ice-creams frozen and have the option of an on-board battery driven freezer. Many tricycles double up as a coffee or hot dog cart or serve other kinds of hot meals in winter (just replace the freezer with a heater).

Modern ice-cream tricycle

This cute little baby is an electric tricycle with battery-operated on-board ice-cream freezer and will set you back USD1450 (ZAR26 000). There are many versions which are cheaper and the pedal versions start at around USD 800.00 (ZAR 14 400). Most ice-cream tricycles tend to favour a ‘vintage’ look, but there are many which are completely modern in design and some models even have a solar powered freezer system for the environmentally conscious vendor.

Sources

- Arias J. (20190. Informal Vendors in Johannesburg, South Africa. Penn Institute for Urban Research. PENN IUR Series on Informality. https://penniur.upenn.edu/uploads/media/05_Arias.pdf

- Bénit-Gbaffou C. (2016). Do street traders have the ’right to the city’? The politics of street trader organisations in inner city Johannesburg post-Operation Clean Sweep’. Third World Quarterly 31(6).

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and has worked in the agricultural sector doing crop biotechnology research. She recently spent five years at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, coordinating an African mountain science network funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). During this time she organized two mountain research conferences, one in Ethiopia and one in Tanzania. She is a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.