The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation in conjunction with the Urania Village Community recently organized a walking tour of the Johannesburg Observatory and the surrounding streets of old Observatory. Observatory is a Johannesburg suburb dating back to the early 1900s, when part of the Bezuidenhoudt Farm was in part sold and in part given for the establishment of this scientific institution under the director R T A Innes. The Observatory is located at the highest point on the hill overlooking the suburb. The topography is typical of the ridges of the Witwatersrand.

Observatory Buildings from the South (The Heritage Portal)

Some very attractive homes were built over the years in surrounding streets (many named for astronomers). Johannesburg’s oldest extant golf club and course, the Observatory Golf Club was founded and the course laid out in 1913. Observatory is also a suburb of some important well established educational institutions such as the Observatory Girls Primary School and the Sacred Heart College. The Johannesburg Children’s Home is yet another long time established home for all of Johannesburg’s children who through the years were in need of care.

Johannesburg was a boom mining town in the 1880s, a very ad hoc affair and no one knew how long the search for wealth and riches would deliver results to keep the gold diggers here. Early Johannesburg was a place of chaos, vice, disorder, bars and a heavily masculine hub. However, within a few years, the mining camp had become a town, and a more normal domestic scene began to show a confident permanence with families settling and schools, churches and sports facilities established.

Early School Buildings in Johannesburg - Initially St Mary's College now St James Prep (The Heritage Portal)

One need for the emerging town that was quickly recognized by civic minded women was that there were children whose parents could not care for them. The honour of establishing a children’s home for the city goes to Lucy Matthews the wife of a prominent doctor who started a home or perhaps more accurately described as a crèche when she rented two small rooms in a house in Fordsburg in 1892 where mothers could leave their children. These were the small beginnings that ultimately grew into Johannesburg’s premier child care institution, the Johannesburg Children’s Home. It prided itself on being “undenominational” (what a peculiar word!) or a place that did not define child care in terms of the religious background of the family in need. The Home became the Johannesburg charity that was warmly embraced and supported by the city, though there were ups and downs. JCH was a sanctuary for children who mainly had only one living parent. Fund raising had to be undertaken from the earliest days, appealing to the conscience of the town’s citizens but also raising debates about whether caring for children would not set a precedent and encourage illegitimacy. It is fascinating to read about the early years of the home, which was given eight stands on Hospital Hill but it seems there was no building undertaken and permanent premises were acquired in Beit Street Doornfontein in 1896.

Of course there were other children’s homes in the city such as Nazareth House (established by the Catholics), the Jewish Orphanage (later called Arcadia) and then the Abraham Kriel Children’s home in Langlaagte. Illegitimacy was only a minor cause of child indigency. In the early 20th century, life spans were shortened for working people by mining accidents, death in child birth, miners’ phthisis and the consequences of wars.

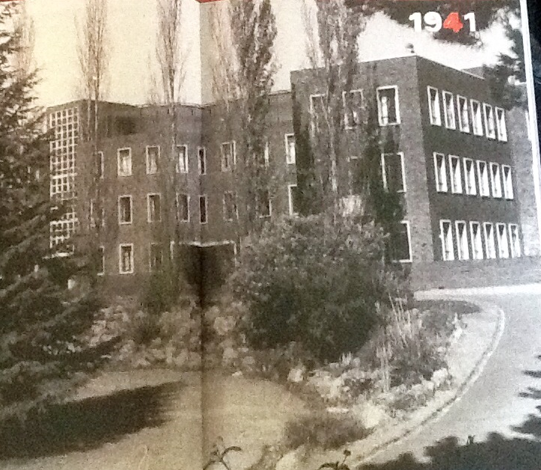

In 1904 the JCH made the decision to move from Doornfontein, and purchase ten acres in the then newly establish country suburb of Observatory on the outskirts of the city. The home made a good neighbour to the observatory, and its first purpose-built building was built. By 1940, 109 children were accommodated and a new building was designed and erected (the architect was Norman Eaton and Fair). Isie Smuts laid the foundation stone. That building is still extant but has been sold to Rand Tutorial College.

The Norman Eaton and Fair 1940 home

This book captures the history, hurt, heartaches, hopes and triumphs of the Johannesburg Children's Home through the decades and confronts in a very readable and thoughtful way the controversies around social work practice, the changing theories of how kids in need should be cared for and what happened in an institutional setting. It is sensitive and honest, for example in discussing patronizing attitudes of donors and the difficulties of being a poor child in receipt of charity by well-meaning kindly people. There were many people who cared about Johannesburg children in need and their fate. The good ladies of Johannesburg and the city fathers worked hard to raise funds and there were some outstanding contributions made with bequests and fund raising. Eddie Magid (Joburg mayor in 1984), Adrian Steed, Desmond and Patricia Niven were dedicated backers of the Children’s home. Many of the staff were heroic in their devotion to the children in care. Nonetheless one is appalled to read that in the early years the children were expected to move into employment from their early teens, and be trained for useful jobs. The prospect of changing their circumstances was severely circumscribed by the limited educational opportunities for institutionalized kids. But an amazing young woman in the eighties, Charlotte Harvey became the home’s first University graduate and an impressive role model. Many children as they grew to adulthood remembered their years at the Children’s Home with affection as it was their "home“ and they made the best of their circumstances.

Book Cover

The book is filled with fascinating newspaper clippings, original archival documents and poignant letters from desperate parents and some wonderful early photographs. The story of child care is brought up to date with the changing practice of now caring for children in far more home like circumstances with cottages built on the lower section of the property (here the architect was Gerald Gordon) in the 1980s. 8 to 10 children live with house mothers and fathers in the Cottage System. Originally the home, in keeping with the ethos of the times, was an all-white establishment but by the eighties racial barriers began to give way to a more inclusive approach and by the late eighties and early nineteen nineties the Home was beginning to position itself in the New South Africa. New programmes were established by innovative directors. The book does not gloss over the problems of possible sexual abuse when a more intimate home environment was replicated and the specific case uncovered has been written up with honesty and sensitivity.

This is a lovely book, quite beautifully illustrated with children’s’ art and with pages of colourful contemporary photographs. It is well written and well researched by David Saks and Lynn Barnes. I liked their readiness to avoid sugar coating the issues so that the book moves beyond a public relations exercise. Company histories could learn from their handling of the archive. The book captures an important dimension of Johannesburg history and is a book that should be added to your book collection on the city.

Any criticisms? I would have liked more on the architecture and design of the Eaton building (surely it deserves a blue plaque). I also would have liked this institution’s history to have located the Johannesburg Children’s Home in the history and ambience of the suburb. Finally I would have liked more information about other child care facilities in Johannesburg; why was JCH different (or was it the same) when compared to other Johannesburg child facilities? How did JCH fit into the bigger social picture? There is no discussion about restricting life’s choices because adoption was not a possibility. Nonetheless, I recommend the book.

2017 Guide Price: The book (hard cover) may be purchased for R150 ( and comes with a cloth book bag) from Fiona Duke at the home (45 Urania Street, Observatory, tel 011 023 6870/1).

I thank the Home for their donation of a copy for the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation Resource Centre Library.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.