Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The primary photograph under discussion in this article is the 8-pane panoramic photograph of early Johannesburg (1888) by the photographer David Hyman Davies.

The 270° panoramic photograph was obtained from a Pretoria-based resident who stated that the image had significant relevance to the family back then in that a great-grandfather (one J. van den Berg) was a wood transporter between Port Elizabeth and Johannesburg. The Scott Guthrie & Co timber yard, on Pritchard Street, can also be seen on the far left of the image where van den Berg would have delivered the wood.

The photograph was captured from the roof of the double-storey Arcade building (on the corner of Rissik and President Streets – where the Barbican building stands today).

Davies would have used an ordinary wet-plate bellows camera and lens to capture each image which were then pieced together to produce the panoramic image. The camera would have been carefully pivoted on a tripod with a series of exposures of slightly overlapping aspects of the same view. Following the exposures, Davies would then have developed the images, trimmed the resultant segments, and pieced the individual images together to produce the final panoramic view.

The photograph, pasted onto a cloth-like material, 1.8 meters in length, sadly shows signs of deterioration following its 137-year existence.

On collecting and paying for the photograph, I was informed that if I were not interested in the photograph, the image would have been discarded in that there no longer was any interest in the photograph within the family. The photograph is now safely curated in the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (HPRC).

Lo and behold, on a privileged visit to the Johannesburg Rand Club in January 2025, I spotted what I thought was exactly the same photograph - a 12-pane photograph in the most impressive wooden frame – some 4 meters in length, each photograph in a slightly larger format than the Davies images. But it turned out not to be the same – it is exceptionally similar though. The Rand Club photograph, by the photographer B. Ellot (a previously unrecorded photographer within the Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection), was captured a year after the Davies image, from exactly the same spot as the Davies image – from the top of the Arcade building. The 1889 Ellot image is unusual in that it is also a full 360° image, begging the question of whether the Davies image also was a full 360° image at one point.

Ellot probably saw the Davies photograph and elected to copy his idea. The Ellot photograph shows less activity in and around Market Square compared to the Davies photograph. The rest of the surroundings remained pretty much the same. The construction of the double-storey on the corner of Rissik and Market Streets (thought to be the Goldsmith Alliance building) is also still in progress on the Ellot photograph.

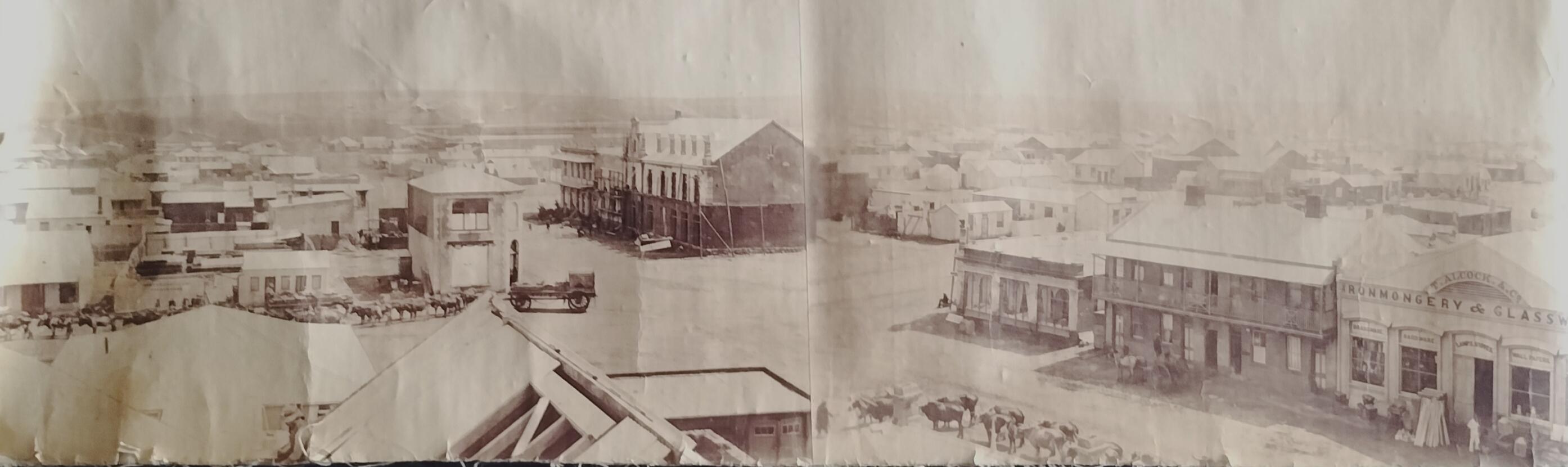

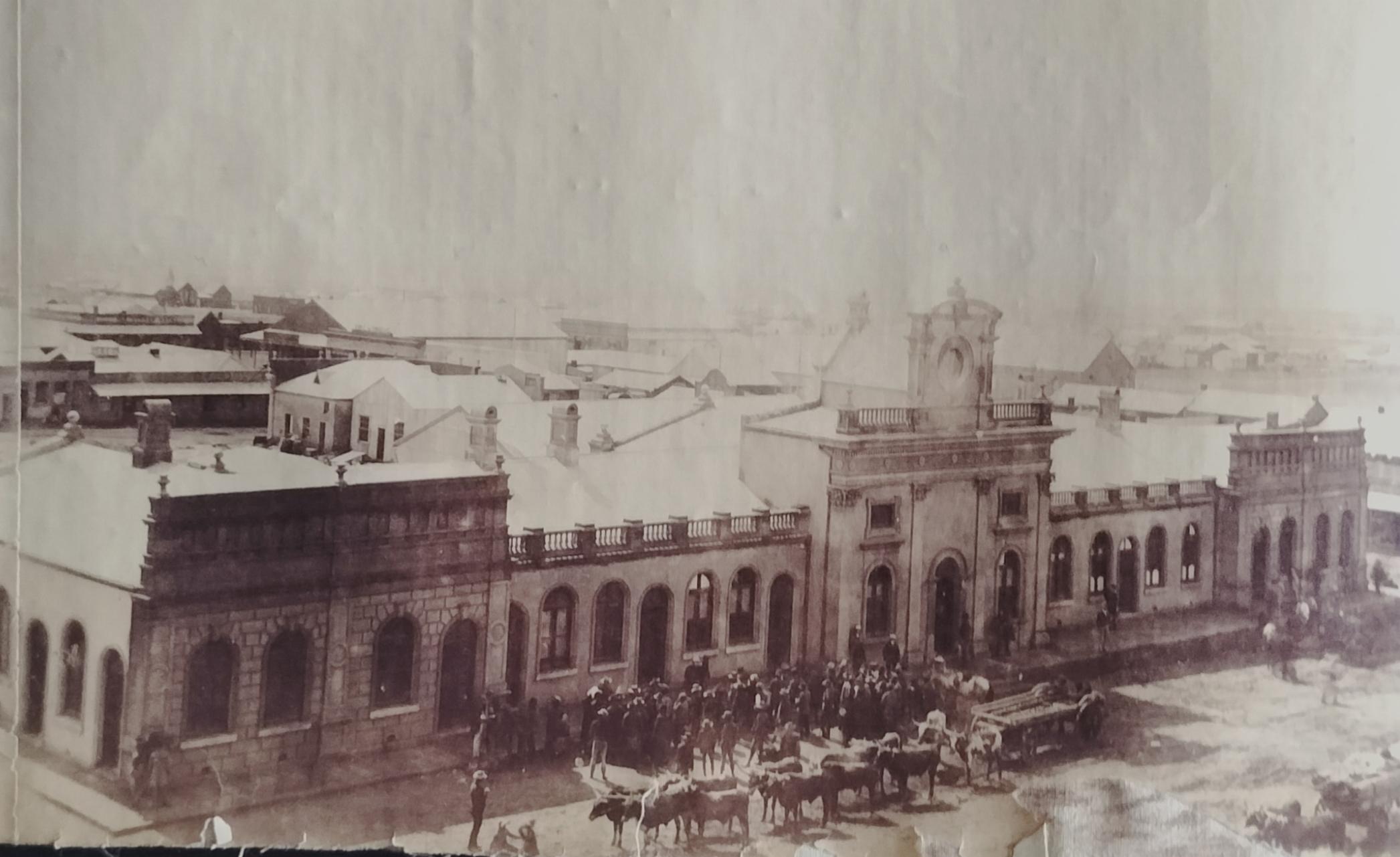

First 2 panes of the 8-pane panoramic photograph captured by Davies in 1888 looking north showing Rissik and Pritchard Streets

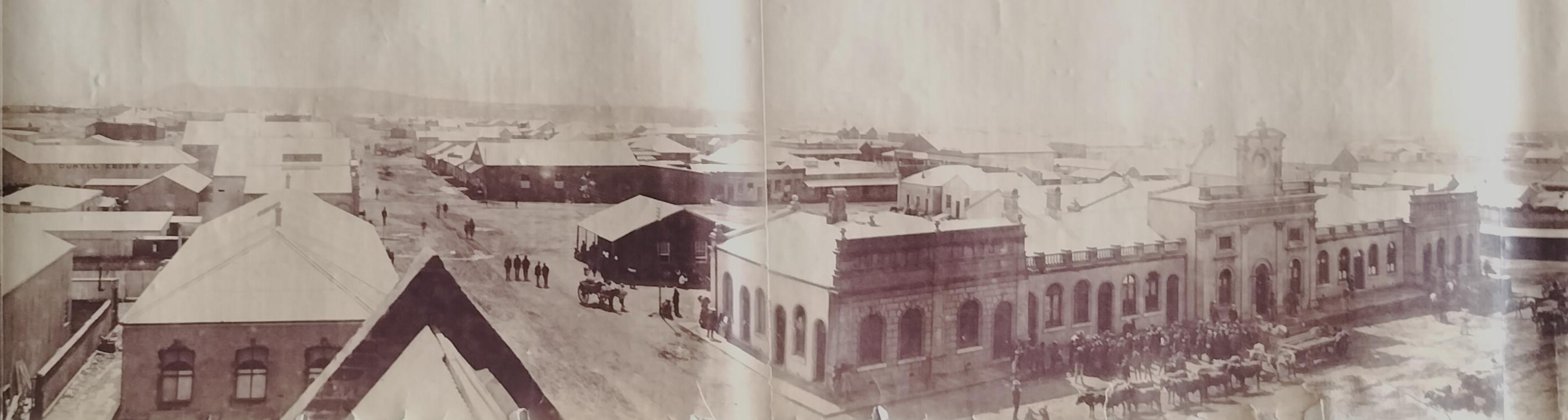

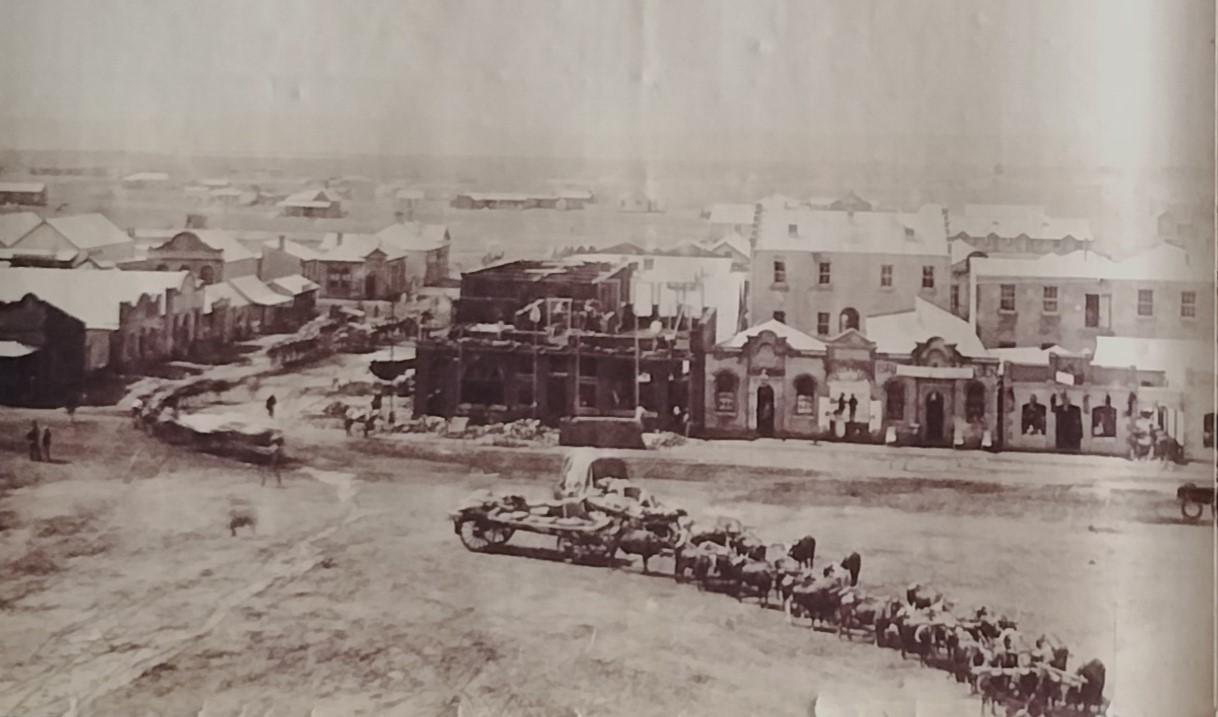

Pane 3 and 4 of the 8-pane panoramic photograph captured by Davies in 1888 looking east showing President and Rissik Streets

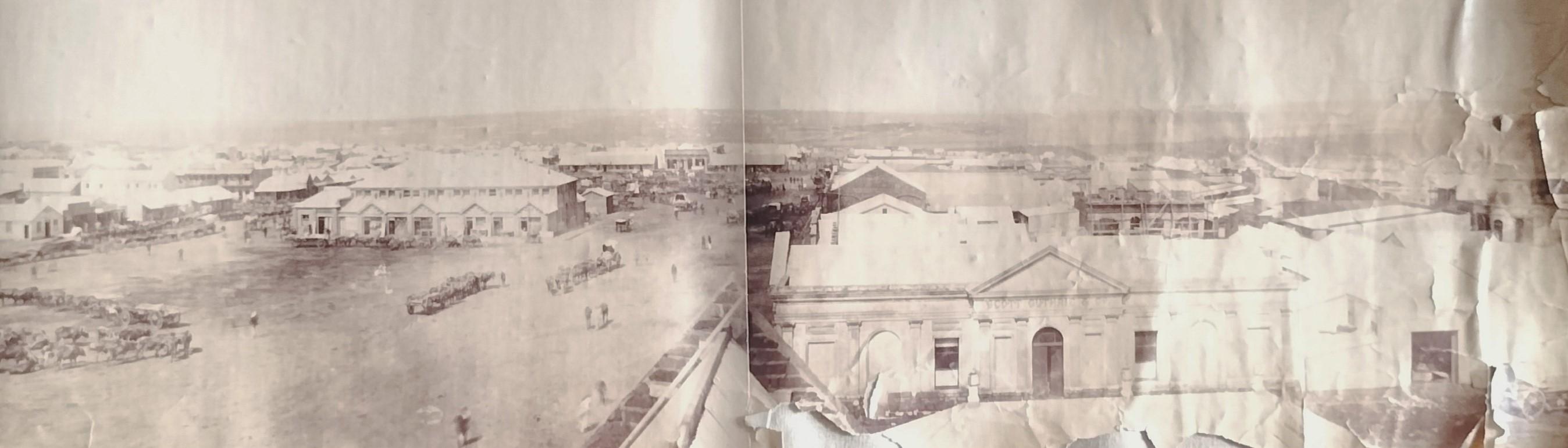

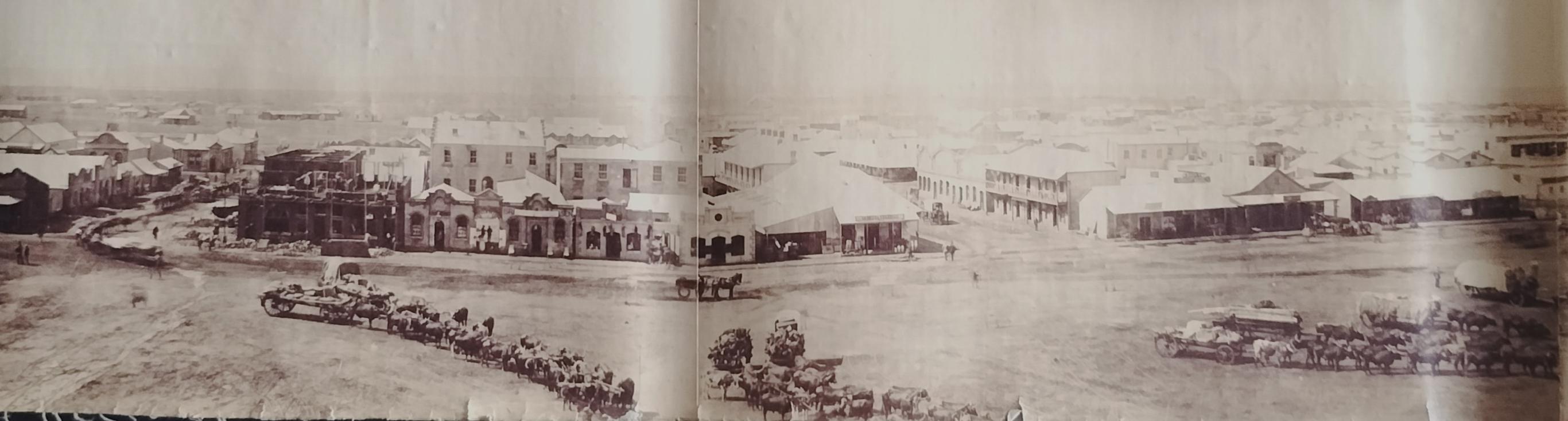

Pane 5 and 6 of the 8-pane panoramic photograph captured by Davies in 1888 looking south showing part of Johannesburg Market Square. The streets visible are Rissik, Market and Loveday Streets.

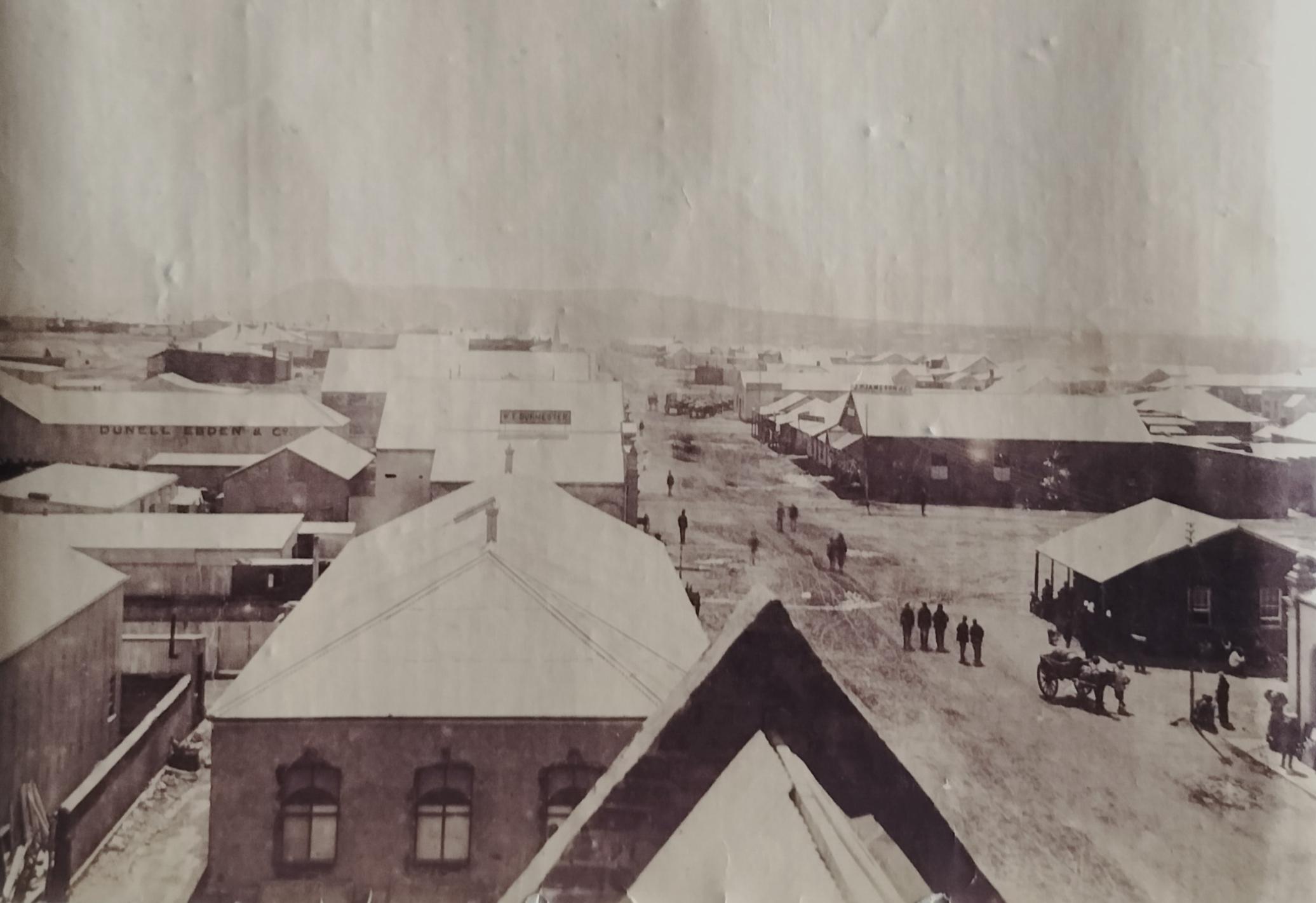

Pane 7 and 8 of the 8-pane panoramic photograph captured by Davies in 1888 looking west showing part of the Johannesburg Market Square.

History of panoramic photography

A panorama consists of a single photograph or series of photographs that encompasses a sweeping view.

Panoramic photography soon came to displace paintings as the most common method for creating wide views.

Shortly after the invention of photography in 1839, the desire to produce overviews of cities and landscapes prompted photographers to create panoramas. The first panoramas were made by placing two or more daguerreotype plates side-by-side. Daguerreotypes, the first commercially available photographic process, used silver-coated copper plates to produce highly detailed images.

Only six years after the invention of photography, Friedrich von Martens invented the first panoramic camera (1845), called the Megaskop-Kamera. This camera featured a swing lens and was operated by a handle and gears. The first model used 12cm x 38cm curved daguerreotype plates. A later model used wet plate curved glass emulsions. The curved plate design made development of the plates difficult, however, von Martens managed to produce many high-quality panoramas. In 1851 he had the opportunity to exhibit several albumen prints of architectural views at the Great Exhibition in London, for which he was awarded the Council Medal. In the 1850s von Martens decided to try taking panoramic photographs using talbotypes instead of daguerreotypes. He tried this new idea while photographing the Alps. One of these photographs, taken of Mont Blanc, in fourteen parts, was exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. Today, eleven large panoramic daguerreotype plates of Paris are still in existence that can be reliably attributed to von Martens.

An 1851 view of San Francisco was also made with five daguerreotype plates. It is believed that the panorama also initially had eleven plates, but sadly the original daguerreotypes no longer exist.

Producing panoramic prints became so advanced that HH Bennett could print three or four almost 51cm x 61cm sized negatives onto an enormous sheet of paper with almost no indication of where the negative edges met.

From the Daguerrean era onwards, many varieties of panoramic cameras have been invented. In one kind of camera, the film is mounted on a curved back inside the camera where the lens automatically turns on an axis. A continuous exposure is made onto the film through a narrow slit moving with the lens.

Another camera itself rotated, and the film moved past a slit at a speed coordinated with that of the rotation of the camera.

During the American Civil War, military engineers and generals valued panoramic overviews of terrain and fortifications. These panoramas were printed from two or more wet-plate glass negatives that were exposed in a conventional camera. The wet plates had to be coated with an emulsion, sensitized, exposed, and developed in the field while the plates were still wet. After each exposure, the camera was rotated to the next section of the panorama to produce a new negative. Upon return to the studio, the photographer would have made a print from each negative by placing a sensitized sheet of photographic paper on the emulsion side of the negative in a printing frame. The frame was placed in the sun until the prints achieved the desired density. The prints were then fixed, washed, trimmed, arranged, and mounted to form a panoramic photograph.

Towards the late nineteenth century, cameras were commercially manufactured for producing panoramas. These cameras were either swing-lens cameras, where the lens rotated while the film remained stationary, or 360-degree rotation cameras, where both the camera and the film rotated.

The first mass-produced American panoramic camera, the Al-Vista, was introduced in 1898.

In 1899 Eastman Kodak introduced the No 4 Kodak Panoram panoramic camera that proved popular with amateur photographers.

In 1904, the Cirkut camera was introduced. This camera was based on the principles that had been established in the 1840s. Although unlikely that this camera ever reached the South African shores, it became a popular format for commercial photographers abroad and was used to make large group portraits or capture city scenes. It used large film that ranged from 12.7cm to 40.6cm wide and could be as long as 6 meters! Both the camera and the film rotated, and the view could achieve the maximum 360°.

Subsequent mass-produced panoramic cameras worked on the swing-lens principle, used roll film and did not need a tripod. They were also able to produce smaller panoramas, measuring no more than 30,5cm long with a field of view of almost 180°. Developing the film was easy, and the resulting negatives could be contact-printed or used for enlargements.

Unlike conventional cameras, many panoramic cameras distort images where distortion occurs as the distance between the lens and the subject changes. Distortion is most evident in street scenes where the camera is positioned at the intersection of two streets. In such a panoramic image, the straight street, which is parallel to the camera, will seem curved.

The building seen on the corner of Rissik and Pritchard Street (behind the ox wagons) was a wood storage facility (Scott Guthrie & Co - Timber yard). At the bottom, in the middle of the photograph, a man can be seen working on the roof structure of the building from where the photographs were captured by Davies. In the background the Wanderers stadium can be seen.

Rissik Street - The building on the right belonged to the iron monger and glass merchant T. Alcock & Co

On the left, middle of the photograph, the signage of Dunell Ebden & Co can be seen. Just to the right of that is the sign WE Burmester (Printers and Book binders). Also see the JP Jameson & Co sign. It must have rained a few hours before the photograph was captured in that President Street shows up as wet and muddy. Also note the telegraph poles.

The Government offices, which acted as the administrative hub for Johannesburg for 9 years. The architect was the German-born and educated Hans Victor Lindhorst (1860-1912). This building later became the Post Office complex (1897). In front of the building is a group of Black citizens seemingly listening to a man standing in uniform. Note the ox-wagon on the right. At the time Davies captured the 5th pane, the ox wagon has long moved on, affecting the flow of the image.

Brief history of panoramic photography in South Africa

To date, it has not been confirmed who the first South African professional photographer was that would have captured a panoramic image.

It has however been recorded that the first panoramic images captured on South African soil may have been produced by a Cape Town-based amateur photographer William Morton Millard (1859). Looking at the photographs captured by Smyth at the Cape Royal Observatory (Glass, 2023), I cannot help but wonder whether some of his photographs may have been panoramic as well – Unlikely, but still an important question to ponder over.

Considering that the first recorded panoramic image by a professional photographer, captured in 1864, was by King Williams Town-based Carl Bluhm (1864 – 1882), it is safe to accept for now that Bluhm, who became a prolific panoramic photographer, was South Africa’s earliest professional to have adopted the challenging technique of panoramic photography. The Amathole Museum in King Williams Town (Qonce today) curates some of Bluhm’s early panoramic images.

The Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection also contains a Cape Town panoramic (circa 1865) by an unknown photographer. It is speculated that the photographer of this image may have been William Bremner.

The building under construction (corner Rissik and Market Street) is thought to be the Goldsmith Alliance building. On the right of this complex, the first of two similar looking buildings (referred to as the Temple Chambers) are linked by a high gate (two men can be seen standing in the high gate). The first of the two (on the left) is the Temple Bar with the second (on the right) the business Isreal & Ohlsen. The second set of similar looking buildings (also linked by a high gate), are Altenbach Watchmakers/Jewellers whilst the second was occupied by Loewenstein Chemist and Druggist (overlapping into image below).

The building on the corner of Market and Loveday Street was occupied by the merchant MM Steytler. Note the horse in front of the Druggist store. This same horse cart was not present when the preceding image was captured by Davies. The next four buildings between Loveday and Harrison Streets are: Isreal & Ohlsen Stationary and Fancy Goods, The Birch building, Wepener Bros & Cairncross and finally (far right), the business S. Jacobs & Co.

The building in the centre of the square, between Simmonds and Harrison Streets is the market building.

This image completes the 8-pane photograph. It again shows the roof structure of the Arcade building from which the photograph was captured. The building in front is that of Scott Guthrie & Co. The resultant panoramic image presents a 270° scene of early Johannesburg. Excluded from the image is the north-western portion of Johannesburg.

Photographer - David Hyman Davies (1853 – 1916)

Although it is not known when Davies landed in South Africa, he first established himself as a photographer in Port Elizabeth before relocating to young Johannesburg, where he based himself between around 1887 and 1895. A British census indicates that the family was back in England by 1901.

Davies was born in Sheffield, England in 1853. He was married to Matilda Davies. The couple had 5 children. Davies died in England on 24 July 1916, aged 63. His brother Samuel, with whom he was in partnership as a photographer, signed his death certificate. Davies is described as a master photographer on his death certificate.

Closing

Not all photographs, panoramic in nature, have always been pieced together after the panoramic view was captured by the photographer.

One such example is the work by the Scottish photographer, George Washington Wilson, who extensively photographed South Africa before the 1900s (click here to read more).

In researching his work, some five single images, captured in Cape Town, have been identified and when placed next to each other produce the most incredible panoramic image of early Cape Town. This suggests that more early imagery, unbeknown to the contemporary viewer, actually forms part of a larger panoramic view.

Ongoing research will have to confirm which other early South African-based photographic pioneers would have produced panoramic images before the 1890s.

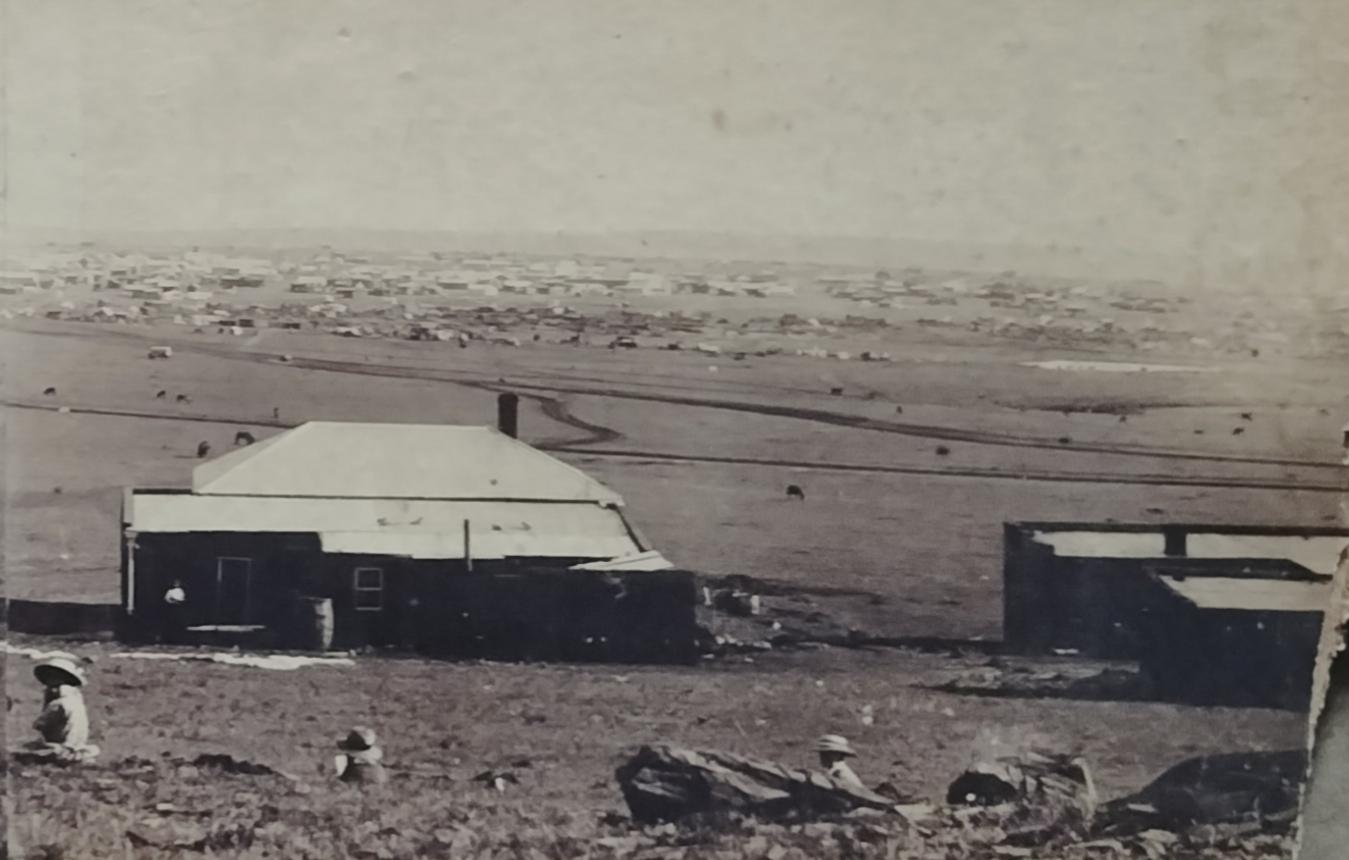

A two-pane panoramic view of Johannesburg (circa 1888) by an unknown photographer. Note the family of 4 seated on the "koppie" behind their homestead. Although the exact location of the image is unknown (possibly from Hospital Hill looking South onto the rapidly developing town?), it clearly captured life in rural Johannesburg.

Pane 1 of the two-pane panoramic view above. The photographer first took this image whereafter he would have moved his camera (mounted on a tripod) to capture the second image (pane 2 below). The horse-cart rider is also posing for the camera.

Pane 2 of the two-pane panoramic view above. The lady standing in front of her house in the background (with white top) is also posing for the photographer

Special Acknowledgements

- Prof. Kathy Munro – for sourcing a copy of the van der Waal brochure which better enabled me to identify earlier Johannesburg buildings

- Marc Latilla – for confirming the building name from which the photograph was captured (click here for some background)

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Addis, M. & Hardijzer, C.H. (2021). Carl Bluhm’s contribution to early Eastern Cape Photography – A career tragically cut short (theheritageportal.co.za)

- Baldwin, G. (1991). Looking at photographs – A guide to technical terms. J. Paul Getty Museum, California & British Museum, London

- FamilySearch (extracted December 2024). David Hyman Davies.

- Glass, I.S. (2023). The first photographs made at the Cape of Good Hope. South African. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 26(3), 731–752 (2023).

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2021). Operators of Mirrors with memory – South African Photographers 1846 – 1915 (theheritageportal.co.za)

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2020). George Washington Wilson – The man, the company and the photographers (theheritageportal.co.za)

- Lemke, J (2022). Seeing the whole picture with Panoramic Cameras.

- Latilla, M. (unknown). Johannesburg 1912 – Suburb by suburb research

- Latilla, M. (email communication 5 March 20205). Email communication between Hardijzer and Latilla confirming building from which the Johannesburg panoramic view as captured

- Munro, K. (2015). What did Johannesburg look like in 1889? (theheritageportal.co.za)

- Unknown (extracted 19 January 2024). A Brief History of Panoramic Photography. Library of Congress.

- Unknown (extracted 19 January 2024). History of Panoramic Photography. University of Washington Digital Collections.

- Unknown (Extracted 19 January 2024). Panorama. Wikipedia

- Unknown (extracted 19 January 2024). Von Martens Megaskop Panoramic Camera Patent Document. National Museum of American History

- Van der Waal, G.M. (1971). Die Markplein van Johannesburg. Katalogus van geboue om en op die plein tot omstreeks 1920. Johannesburg Public Library brochure

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.