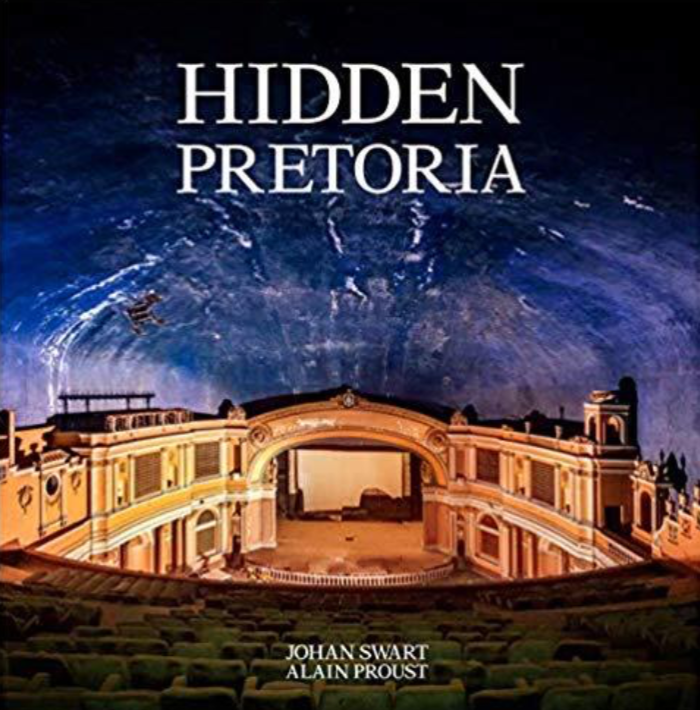

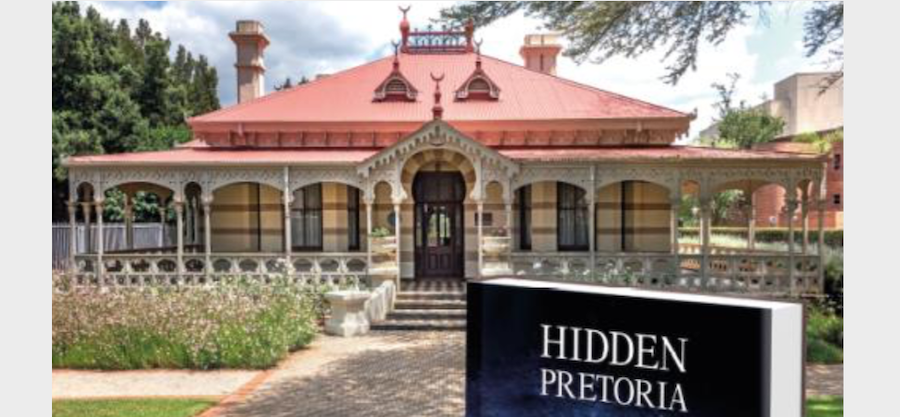

We have all been looking forward to the appearance of Hidden Pretoria and we are not disappointed. The launch took place in October at the University of Pretoria on a clear starlit night under a magical crescent moon. It was a beautiful evening, the stylish launch comprised a three way conversation about the book, a photographic exhibition of Proust’s Pretoria images, and a sales table manned by Protea books. Johan Swart and Alain Proust have collaborated successfully as author and photographer to provide a visually rich book backed by a series of balanced essays on each building or theme. It is a generous sized volume that unlocks some of Pretoria’s treasured buildings. Some of the buildings are well known, others less so. The success of the collection lies in that combination of quality research about a building (Johan Swart), and a photographer as an artist in the medium (Proust). I congratulate the partnership for providing the best book to date in this format. There are some welcome and thoughtful innovations.

Book Cover

Hidden Pretoria is the third in the series released by Penguin Random House under their Struik Lifestyle imprint and parallels the independently published Inside Kimberley. The earlier volumes had Paul Duncan as author and Alain Proust as the photographer. Inside Pretoria breaks new ground with the architectural historian and academic at the University of Pretoria, Johan Swart as the author and seasoned lens-man Alain Proust retained as the photographer. This book is as gorgeous and visually appealing as the earlier titles. This is a quality production well worth acquiring.

As the next in the series it completes a trilogy except that we still need to see Durban, Bloemfontein, Pietermaritzburg and other towns and cities given the same treatment.

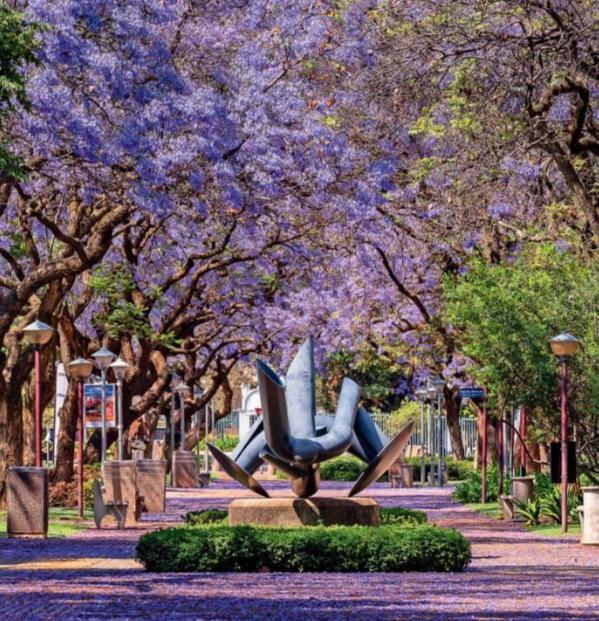

Eduardo Villa sculpture on the route to the University of Pretoria's Law Buildings during Jacaranda season

This is a book that gives pleasure in paging through the many images and the emphasis falls on the photographs; but I advise you to pause and read the accompanying essays and the informative captions. The typography and layout are totally professional with all photographs, clear and large and in beautiful colour. The text is perhaps a little small, especially when one wants to concentrate on the essay content but that is a quibble for the editorial team. This volume will appeal to everyone with an interest in the heritage treasures of South African cities; here is an important form of documentation. For the heritage community there is an optimistic message about the value of documentation and conservation of city buildings, although there is a subtext about the problems of urban decay and neglect in the 21st century in cities that battle with management, expertise and finance. As in the case of the Johannesburg volume it is a book that makes a citizen of Pretoria look at his town with new eyes and fresh delight and feel a pride in citizenship.

It is a coffee table book that brings us the author and photographer’s choice of buildings representative of Pretoria’s architectural legacy and in this selection there are some inspired surprises as well as some surprising omissions. But this is what makes this book so appealing – it is a personal choice, it is visual with the possibly more than two hundred splendid coloured photographs; it is these images that give an almost sensual lushness; in fact all the senses are engaged. The quality of photographs means one can feel, touch and almost smell all these public and private spaces and places of old and new Pretoria.

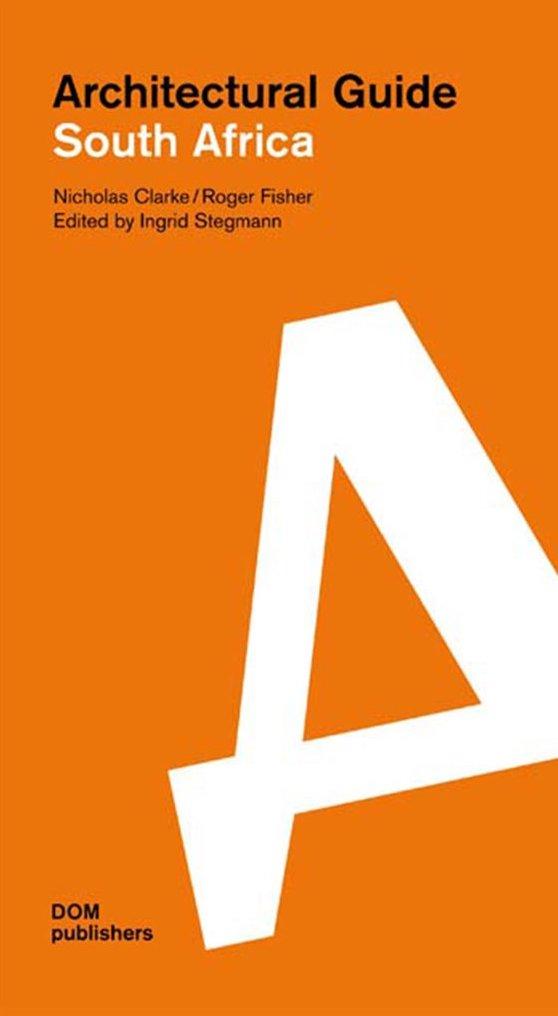

One only has to turn to Doreen Greig’s Guide to the Architecture in South Africa (Timmins 1971) to realize how much architectural photography and book production has progressed when it’s a “big number” quality handsome book. I also dipped into the recently published pocket guide, the Architectural Guide South Africa. That small book has a good chapter on Pretoria – My Pretoria by Mo Phala and is an excellent introduction and overview of Pretoria. The new Swart and Proust book overlaps to a degree but has the advantage of being a bigger and more glamorous publication for armchair enjoyment rather than pocket guide on foot. Of course there are other books on Pretoria such as Viv Allen’s Kruger’s Pretoria and Meiring’s Pretoria. All of these other titles point to overlap but also different choices and remind us how each and every book on a city is unique to the author and documents what exists at a moment in time.

Book Cover

Hidden Pretoria offers an unusual mix of the public and private spaces, exterior views and interior nooks and secrets. There is by no means a comprehensive or systematic list of all Pretoria architects but there is enough of them to get a sense of the artists and architects of the city and the traditions that shaped this capital city. Pretoria was founded in 1855 and in 1860 was proclaimed the seat of government of the South African Republic. Pretoria in historical guise was always quite a small place, located in the bowl of Magaliesberg Hills. Its political history tossed it between its republican identity of Kruger’s Republic and the series of British colonial takeovers in 1877 and then again in 1900 when Pretoria became an occupied city. 1910 saw the creation of the Union of South Africa and Pretoria thereafter emerged as the country’s national, diplomatic and higher education capital. Pretoria evolved over a long period of time, it has an august confidence and industry and the heart throb of the country, mining eludes the city.

Pretoria has always benefited from its tax levying capacity and the flow of funds from its brasher neighbour 65 kilometers down the M1, the economic and industrial core of the country, Johannesburg. Pretoria’s character in the 20th century revolved around that of apartheid national administrative capital and provincial capital of the then Transvaal. It was and still is an educational centre with two major universities and many fine schools, a location of scientific research complexes, a central prison and the diplomatic core. Government ran the country from Pretoria with the Union Buildings the imperial masterpiece of Baker on Meinjeskop proclaiming the purpose of rule. Today Pretoria is still the capital, the American embassy astounds with its bunker like design but greater Pretoria is called Tshwane. These days I am not even sure where Pretoria ends and Tshwane begins. The introduction alludes to the diverse narratives of the city, but a little more on the economic, military and demographic context of the city, both then and now would have added value. You will need to look elsewhere for data about size and population or basic facts as to how many embassies there are. This book makes no bones about being a heritage homage.

The end papers should be savoured as they show Walter Battiss’ work for the TPA building, The Transvaal Sanctuary. A new feature of this book are the many double page panoramic spreads of interiors and skylines that enables the details to be blown up and visually savoured.

It is a grand heritage. The photographs convey the sense of place and the photographer succeeds in both finding and creating “atmosphere“. The cover photograph is of the very atmospheric Percy Rogers Cooke and John Ralston interior of the Capitol Theatre, but even more extraordinary is the photograph of the auditorium of the Capitol with cars now parked, where people once sat in the stalls and were transported to Hollywood in a faux Renaissance setting under an Italian sky. What could be more symbolic of changing times and city loss; but at least we can still marvel at this folly and fantasy whereas the companion theatres the Alhambra in Cape Town and the Colosseum in Johannesburg are gone.

The photographs are particularly beautiful of the Capitol, but it is almost impossible to pick a favourite photo or favourite place. There are photographs of the obviously visible facades and wide angle shots but there are also the close up views of the hidden surprises, of details and features that lie behind and beyond in interiors and in quiet courtyards. If I have to choose, my favourites are the images of staircases and stairwells which reveal the diversity of building materials and their almost tactile textures such as the buildings of the University of Pretoria. At the opening event, there was an exhibition of some of Proust’s photographs for the book, framed, signed and for sale; there was an instant rush and red sold circles made for a sold out exhibition within half an hour. I was thrilled to purchase one of the photographs (my choice was the interior of the Volksraad), but there were at least half a dozen photographs that I would have loved to have taken home.

A key objective of author and photographer has been to create a visual and documentary record of the heritage of Pretoria at the end of the second decade of the 21st century, at a time when we see too much neglect, significant under-utilization and urban decay in South African cities beyond transition and demographic change. An architectural legacy needs an appreciation, a grasp that buildings are for the next generations and that the responsibility of today’s planners and custodians of the city is to understand and grasp the legacy and to find the finance to preserve and conserve. Old buildings have to have a purpose and a use for their past to be meaningful. This is particularly difficult in an administrative national capital but a city which also ceased to be the provincial capital when the Transvaal disappeared (the capital of Gauteng is now Johannesburg). Most worrying is the old TPA building, a Modern Movement masterpiece, inaugurated in 1963, but now mostly vacant. Proust and Swart reveal the remarkable collection of art works and a variety of architectural surprises. There is the Alexis Preller grand work, called Discovery as well as the surprise of the 11th floor preservation of the stained glass windows from the Old Pretoria Chambers and the salvaging and saving of the Hollard House wooden panels, scrolls and leaded glass windows. The building has stood largely empty since 1994 and it has only recently been reoccupied as the home of the Public Works Department. How very quickly a fine lavish skyscraper public building degenerated into a white elephant beached by bureaucracy.

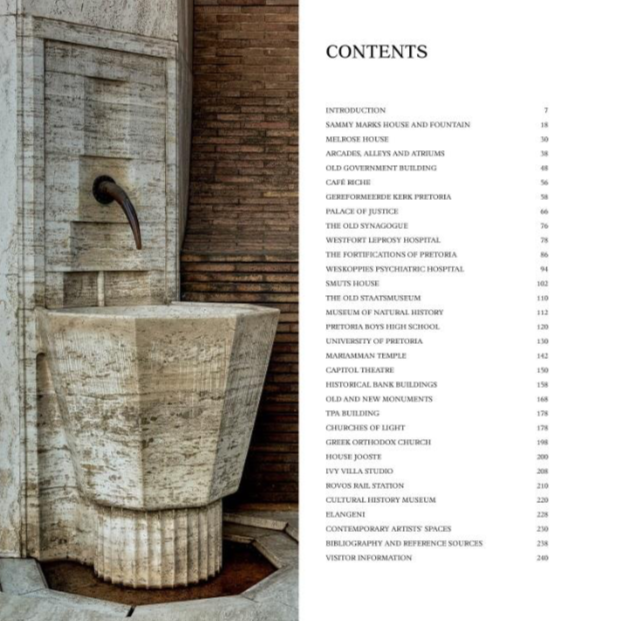

The structure of Hidden Pretoria follows both chronology (starting with an example of the Sammy Marks house as a 19th century home) and theme, though the time frame crosses rigid boundaries. The creativity of the writing remains the driving motor. There are 22 principal chapters covering specific places such as Melrose House, or the Gereformeerde Kerk and the Palace of Justice but then theme based chapters which group together topics such as Arcades, Alleys and Atriums or old and new Monuments or the stained glass windows of Leo Theron in a number of churches. The juxtaposing of the Voortrekker Monument and Freedom Park brings a reflection on the long term view of monument – who are these monuments for and how sustainable are they – it’s a pause for reflection.

Contents page showing the drinking fountain at the new Netherlands Bank

Looking towards the Voortrekker Monument from Freedom Park (The Heritage Portal)

There are two unusual chapters on the Westfort Leprosy Hospital and Westkoppies Psychiatric Hospital and a neat question posed is how can heritage be preserved when there is an urgent demand for converting an unused hospital into housing. The heritage landscape is contested as informal housing occupation insistently makes inroads. There is a wonderful chapter on the Palace of Justice written around the theme of architecture and the law in the late 19th century. Here the question is how do interpretations of important public architecture expressly convey a high legal presence. The Palace of Justice was most recently associated with the Rivonia Trial and Nelson Mandela‘s famous declamatory speech. The photographs of the classical halls, columns, clerestory windows and cupolas contrast with the life and death hopes of the Freedom Charter of 1955 scrawled graffiti-like on the wall of a holding cell. The poignancy hits home.

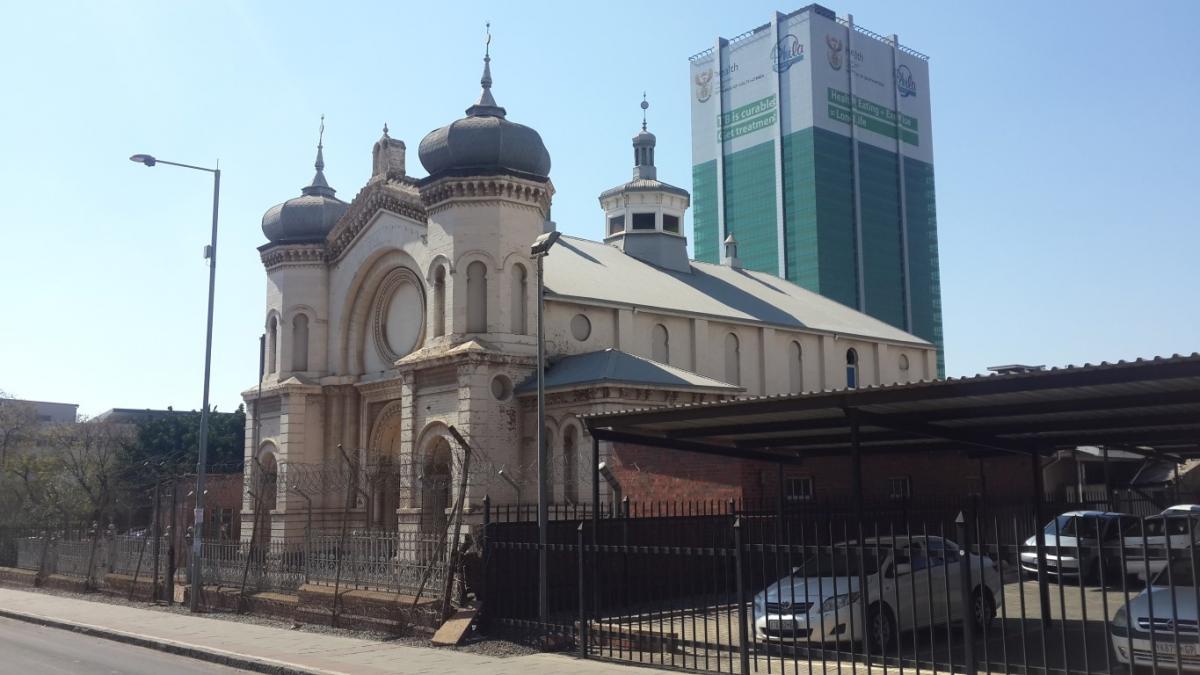

Many of the chapters (though not all) have been extended with inset boxed shorter essays on a related place; for example the Palace of Justice chapter is enriched with the two fine photos and a short essay on the Old Synagogue, which was the site of the Treason Trial, one of the longest running of trials that led to acquittal but was a prelude to the Rivonia Trial.

Palace of Justice (The Heritage Portal)

Old Synagogue (The Heritage Portal)

Of course there are gaps in the book. There cannot but be regret that the authors did not gain access to Herbert Baker’s Union Buildings or Libertas (now Mahlamba Ndlopfu) - the official residence of the President. This is rather like writing a book on Washington DC and ignoring the Capitol or the White House. The reason for the exclusion is that despite South Africa now belonging to all the people, many official buildings are just plain inaccessible - the people who now democratically elect the government are excluded and that then includes those who wish to undertake the most comprehensive and serious of architectural studies. This does not reflect badly on the authors but rather in my mind raises question as to what “we the people” can do to reclaim all our heritage. There is nothing on the University of South Africa – with its great monstrous container ship like presence as you enter Pretoria from Johannesburg (this was the Brian Sandrock 1972 building).

Union Buildings circa 1920

I am grateful that we are compensated by the inclusion of so many unusual Pretoria places which earlier texts might not have rated or ranked. For example, the Mariamman Temple completed in 1928 in the Asiatic Bazaar in Marabastad for the Tamil Community; today somewhat stranded in the urban blight of old discarded rubber tyres, it is a wonderful riot of oriental colour and carved idols. Hidden Pretoria underlines the extraordinary role of the Department of Public Works through the different regimes and favouring different styles of architecture; there is a consistency and high quality in past government buildings and in that Pretoria was lucky though there is also the feel of overarching ambition.

There is a good bibliography of sources for anyone wishing to take research into Pretoria a little further. The final page gives the visitors information for all of the places covered in the text as not all buildings are public ones and not all are accessible to the public. Unfortunately, there is no index and I would have liked an index of the architects, their dates and their key Pretoria buildings. I am not a Pretoria person - my experience of Pretoria is that of the visitor or I will nip in and out for meetings, hence an old fashioned map for me is an essential. A map is a mental guideline and helpful in linking places to one another, showing streets and how to get from one heritage landmark to another.

To end on a positive note Hidden Pretoria is a handsome, visually rich and interesting volume. It adds to the library of Pretoria books and it educates me about the diversity of Pretoria's heritage legacy; documents important buildings, alerts the visitor to extend a visit beyond the city centre. It too becomes a definite must own book.

2019 Guide Price: R439 at Exclusive books. Contact the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation to access the special offer price for members and friends at R400. mail@joburgheritage.co.za

Acknowledgement – Penguin Random House supplied a review copy and provided the poster promotional page and the interior photograph.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.