Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This week’s news reports about the current spike in the Covid pandemic echo down the ages to 120 years ago. Stories about the measles outbreak in the winter of 1901 in the Potchefstroom concentration camp sound eerily familiar with overcrowded hospitals, exhausted medical staff and a lack of beds and medical equipment – and a very high mortality rate.

The only visible reminder of the tragedy of the Potchefstroom concentration camp is a Garden of Remembrance tucked away in a quiet street in the suburb of Baillie Park. Since 1918 a memorial, known as the women’s monument, is standing sentinel. The inscription on the monument reads:

Gedenksteen ter eere van de 967 kinderen, 117 vrouwen en 57 mannen die omgekomen zyn in de kampen alhier gedurende den Oorlog van 1899-1902.

“Hul nachedachtenis sal voortleven”

Onthuld deur

Mev de Wed Gen JH de la Rey

The monument was erected in memory of the 967 children, 117 women and 57 men who died in the camps in Potchefstroom during the war of 1899-1902. “Their memory will live forever.” The monument was unveiled by Mrs Nonnie de la Rey, the widow of General Koos de la Rey. Click here to read my article on the monument.

The death of each person was a monumental tragedy to their family. Multiplied by 1 141, this became tragedy not to be forgotten. This is how it came about.

Backstory

The Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) is well documented. Scholars agree that the main reason for the outbreak of the war was the expansionistic ideals, as propagated by Cecil John Rhodes.

Negotiations to settle the matter failed at the Bloemfontein conference in June 1899, initiated by Pres MT Steyn, president of the Free State and attended by Pres Paul Kruger of the ZAR and the British High Commissioner, Alfred Milner. Britain demanded voting rights for “Uitlanders” (who outnumbered Boers specifically in Johannesburg); use of the English language in the Volksraad; and that all laws made by the Volksraad should be approved by the British Parliament.

Subsequently a large number of British forces accumulated at the borders of the ZAR and on 9 October 1899 Pres Kruger issued an ultimatum for them to withdraw. Their neglect to do so resulted in the ZAR and Free State declaring war on Britain.

The War, which is also known as the Second Freedom War and the South African War, had three phases. In the first phase the Boers scored huge successes with sieges at Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley. The battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein, Colenso and Spioenkop were tactical victories for the Boers.

During the second phase the number of British forces were greatly increased and by June 1900 Pretoria was captured.

The third phase is known as the guerrilla phase, which lasted from about March 1900 for two years till the end of the War. The word “guerrilla” is the diminutive of the Spanish word “guerra” meaning “war”. During this phase Boer commandos attacked British troop columns, telegraph lines, railways and storage depots with “hide, hit and run” tactics. The success of this thorn in the flesh of the British forces were attributed to the Boers being supported by their wives and families on the farms, who supplied them with food and gave them shelter.

On 16 June 1900 Lord Roberts signed the death warrant for thousands of Boer women and children with his signature on Proclamation No 5/1900 which stated: “The houses in the vicinity of the place where the damage is done (attacks on railway lines, troop columns etc) will be burnt and the principle civil residents will be made prisoners of war.”

This is known as the scorched earth policy which implied the burning and looting of farmsteads. Initially it was thought that this would drive the destitute women to the commandos, hampering them in their guerrilla activities.

Boer families who decided to capitulate to British authority were regarded as refugees and encouraged to gather at camps set up for them in towns. Hence, the term “Camps for Refugees” was used by British authorities.

In December 1900 Lord Kitchener, who succeeded Roberts, changed the purpose of the camps, again by proclamation, from giving shelter to refugees to house people forcibly removed from farms.

The Potchefstroom camp was the first of sixteen in the Transvaal (former ZAR). The Free State had thirteen.

First camp at Boys High

It appears that the Potchefstroom camp came into being after the Battle of Frederikstad in October 1900. In accordance with the scorched earth policy, farms were destroyed and people still living on farms in the area were rounded up and taken to Potchefstroom. The 49 mills lining the Mooi River on farms were all destroyed.

Majors Sykes and Edwards, who succeeded him, were appointed as district commissioners for the area and tasked with the establishment of the Potchefstroom camp.

The first camp was situated where the Potchefstroom High School for Boys is today. The school was only founded after the War and opened in 1905. The area for the camp was 22 hectares in extent. This site was chosen because it was near the railway station and water was available from the town furrow who flowed through the camp.

It had four sectors with wide streets which crossed in the middle of the camp. At the crossing were offices, warehouses, hospital tents and the living quarters of the staff. At the outer boundaries were toilets. No bathrooms or bathing facilities were available.

Sykes was not very sympathetic to the plight of the inhabitants of the camp and delegated the management to a twenty-two year old lieutenant. The camp manager was RT Duncan assisted by uninterested shop clerks from Klerksdorp. Subsequently the camp was in disarray.

According to Mrs Rina Ferreira, librarian of the Potchefstroom High School for Boys, the camp was divided into a section for the “better behaved” and one for the “badly behaved”. The inhabitants of the section for the better behaved was housed approximately where the school’s cricket ground is now. The section for the badly behaved was nearest to the railway line.

Some of the artefacts found on the school grounds of Boys High are exhibited in the school’s library and museum. In the middle is the rusted remains of a sewing machine. According to Mrs Ferreira, it was found on the cricket field, where supposedly the “better behaved” inhabitants were housed.

The camp was placed under civil management in February 1901 when the first camp manager for Potchefstroom, Jacob Swart, was appointed. He arrived in Potchefstroom from Johannesburg on a warm February evening, as he later wrote.

Swart was an attorney from the Cape Colony. Earlier he was the secretary of the Johannesburg Turf Club at Turffontein and helped to establish the concentration camp there. Swart was a capable and sympathetic camp manager and endeavoured to improve circumstances in the camp.

Initially one doctor – later more – were assigned to each camp. This post was not always filled and the services of local doctors were used.

There were two camp matrons with a variety of duties. One was in charge of the hospital and other patients and the other one had to see to the distribution of food, clothes and firewood. Some auxiliary nurses were appointed from the townspeople. An experienced midwife was available and a total of 50 children were born in the camp. Some ladies from the town were also willing to help nurse sick people.

The first camp hospital already existed in February 1901 and was housed in a marquee tent.

During the measles epidemic in the winter months of 1901, when there were daily about 280 patients, other tents were also used. Hospitals were installed in two Afrikaans churches. The first was the old church of the Dutch Reformed congregation that stood on the corner of Potgieter and Van Riebeeck Streets (Nelson Mandela and Peter Mokaba). Later the Hervormde Church was also used as a hospital.

Medical care was, however, sorely lacking.

With a total population of concentration camps in South Africa at 150 000, all the large camps, such as the one at Potchefstroom, were heavily overcrowded.

At the end of February 1901 the camp had 2 160 inhabitants and with even more people rounded up, 2 245 were housed in empty houses in town.

At the end of March, the total escalated to 2 221 adults and 3 152 children. This meant that more than a quarter of the total camp population in Transvaal were in Potchefstroom. Only the Johannesburg camp, at the time, was larger. The population climbed to 5 724 in April and 6 348 in June, which made it the largest camp in Transvaal. By September the camp had its highest total of inhabitants with 6 545. In August 1901 the camp housed 3 651 people with between 3 500 and 3 650 in town. The total then stabilised with between 7 000 and 7 250 after other camps opened.

The more outspoken Boer supporters and their families, who came into conflict with the “hensoppers” in the camp, were relocated to camps in Natal. The first group of 225 departed on 17 September 1901. The “hensoppers” were people who capitulated to British rule and came from the English words “hands up”. They were also known as “joiners”.

Prof Van den Bergh wrote in a booklet on the camp, which was published in 1999, that camp life was difficult. The unsympathetic way in which people were sent to the camps was only the start of a hellish experience for most.

Mostly without prior notice, everybody, the old and the young, the ill and the healthy pro- and anti-British inclined, were removed from their homes and were forced to observe the destruction of their farms, furniture and livestock. Initially families could collect a few pieces of furniture and necessities to take with on the wagons transporting them to the camps. Later, when the scorched earth policy was in full swing, houses were literally burned over the heads of the inhabitants and the displaced arrived in the camps with nothing but the clothes on their bodies.

In the case of Potchefstroom people arrived in the camp battered, dirty, dumbfounded and with the signs of hardship.

Conditions in the camp itself were precarious from the start. A lack of tents in the first camp led to the erection of reed shelters covered with tarpaulins for a roof. Sometimes new arrivals were left, for a day or more, even in the middle of winter, without any shelter.

There was a never-ending need for warm clothes, shoes and bedding in the camp. Initially the situation was slightly alleviated with clothes, money and other amenities raised by worldwide camp support funds. This help quickly dried up. Later a tannery was operated in the camp to make shoes.

Although inhabitants could mostly freely move about, a single dilapidated tent was the only home for a family of up to nine people. The ploughed soil in the first camp was muddy and camp children later said that they saw new arrivals who had slept on this ground, woke up in the morning with their hair and clothes brown from the mud. A curfew forbade lights and fires after sundown, so that camp life was monotonous, boring and depressing.

For some the monotony was alleviated by small tasks that had to be performed in the camp and for which there was a small remuneration. Boys helped to keep the camp clean and take care of the tents. Some of the women scrubbed floors and washed clothes for the townspeople in exchange for food.

There was always a need for firewood and the older boys and men were sent to find firewood with an escort of some soldiers. In October and again in December 1901 these groups were assailed by members of a Boer commando.

The younger boys played marbles and made kites. After the camp was moved they could swim in the Mooi River. On 29 November 1902 a Sunday school picnic was organised.

This photo was allegedly taken of the camp children when they were on their way to the north bridge for a Sunday school picnic. They stand in front of the old church of the Reformed Church (Gereformeerde Kerkie). (Postal Museum)

Church services were held each Sunday afternoon in the camp or in one of the church buildings in town. Services were held by Rev Andrew Murray of the Hervormde Church, Ventersdorp. Ladies from the town gave Sunday school classes.

Not enough to live on and too much to die from

One of the major problems in the concentration camp was the lack of food.

At the beginning there were two ration scales, the so called A scale was for “refugees” or those that decided to submit to British authority. The B scale rations were given to the “undesirables” which received half of A scale ration.

The B scale rations consisted of 250 g tinned meat, 250 g flour, rice or samp, 25 g coffee, 50 g sugar, 25 salt and one twelfth of a tin of condensed milk per person per day. Sometimes this was not all available. When meat was available, it was usually tough and stringy and often rotten.

Each family had to collect their weekly food ration from the commissary warehouse, with their ration of firewood. Each family had to prepare their own food on open fires in wind and weather. In addition they could receive what was known in the British army as “hard tack”, nutrionless rusks, generally known under the camp people as “kakieklinkers”.

The disruption of the railway line to Johannesburg by Boer commandos in the area, often led to food stores running low. A mother in the camp said that the food was not enough to live on and too much to die from. Later the B scale was abolished.

Camp school

Education in the camp was not lacking and available on a voluntary basis. But the purpose was to anglicise the children.

The school opened in May 1901 and was under control of JJ van der Merwe.

It was initially housed in a building in town. In October, after the measles epidemic took its toll, another school opened and later a third. By the end of 1901 provision was made for 400 pupils and in May 1902 about 1 000 pupils attended the school, which meant that school took place in two sessions.

Prof J Chris Coetzee, in Potchefstroom 1838-1938, name the head as Arthur Law. He had four local assistants and seven “imported” assistants. One of those was a Miss Bremner, after whom the street to the south of the concentration camp cemetery was later named.

Initially there were six teachers, but by the end of the year there were about 12 and requests were made for another 12. Initially they were locally recruited and could speak Afrikaans, but by the time the camp closed – and with a view to the anglicising policy – one in three teachers came from the British Empire.

Anglicisation was the main purpose of the camp schools. Furthermore teaching methods were less humane than today. This meant that children who dared to speak Dutch or Afrikaans were forced to wear a plank around their neck naming and shaming them as a “donkey”. Many years later a pupil at the camp school still remembered a red-haired English teacher from London who “clamped our head between her legs and made fire on the Boertjie’s backside with a tent rope.”

One of the teachers had the nickname of “Ou Latte”, which meant that he was not afraid to use a cane.

The measles epidemic

By far the most terrifying aspect of the concentration camp was the high death rate of young children caused by the measles epidemic in the winter months of 1901.

The disease was brought into the camps by new arrivals, thought to be coming from Rustenburg. As a childhood disease, measles was not unknown, but this was a virulent strain, a genetic mutation of common measles, that spread like wildfire. What made the effect of the disease so devastating in the camps was that a large group of children were herded into a restricted area. Since they already suffered from malnutrition and exposure, they succumbed to the disease in an unstoppable epidemic way. This was aggravated by the unhealthy circumstances in the camps, inadequate medical care and staff and a lack of hospital accommodation and medical equipment.

Even before the outbreak of the epidemic Swart, the camp superintendent, predicted that the winter of 1901 will be a difficult one due to the lack of warm clothes and blankets and the weakened state of the children. Furthermore that winter is regarded as one of the harshest on record.

The first cases were reported at the end of May in the Potchefstroom camp. In June the epidemic reached its climax. Of the 280 that were ill that month, 237 were children younger than 12. Of the 224 that died 206 were younger than 15. The third week of June was the worst, when 65 children died. The mortality rate for Potchefstroom was the highest in the Transvaal.

One of the families who suffered the most were the De Bruin family of whom six children died. Quite a few families each lost five children. The hearse, collecting corpses, was a common sight in the camp and the funeral processions going to the town cemetery (Alexandra Park cemetery) did not cause any sensation.

The grave diggers could not keep up and as many as six children were buried in one grave. Coffins became unavailable and the corpses were just wrapped in blankets. When Rev JD du Toit, later known as the Afrikaans poet Totius, and his newly-wed wife moved into the manse of the Reformed Church after the War, they found that the floor planks had been ripped out, apparently to make coffins. The manse stood across from the church in Church Street (Walter Sisulu).

The manse of the Reformed Church in Church Street (Walter Sisulu). It was one of the buildings commanded by British authorities to house people for whom there were no space in the concentration camp. Later the house was vandalised and the floor planks ripped out to make coffins. (NWU Museum and Archives)

Camp officials were of the opinion that some of the blame for the high mortality rate was to be laid at the door of the mothers who tried to treat their children with home remedies. This was of no use and they only consulted a doctor when it was too late.

The measles epidemic was by no means the only cause of death of children in the camps. Other causes cited are pneumonia, tuberculosis, diarrhoea, whooping cough and bronchitis, amongst others. Baby Du Toit was only eleven days old when it died, due to convulsions. A six year old girl died of shock after she had been shot in both legs.

According to Emily Hobhouse 27 927 people died in the camps of which 22 074 were children under the age of 15. This must be compared to only 1 118 burghers who died in the prisoner of war camps. In 1901 monthly about 10% of the children in the camps that were the hardest hit, died.

Moving of the camp

Between August and September 1901 the camp was relocated to a healthier area to the east of the town where old Baillie Park is today.

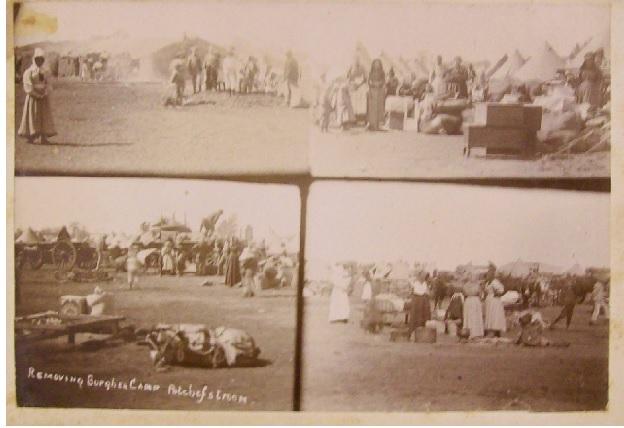

This composite photo shows scenes from the move of the camp. (Potchefstroom Museum)

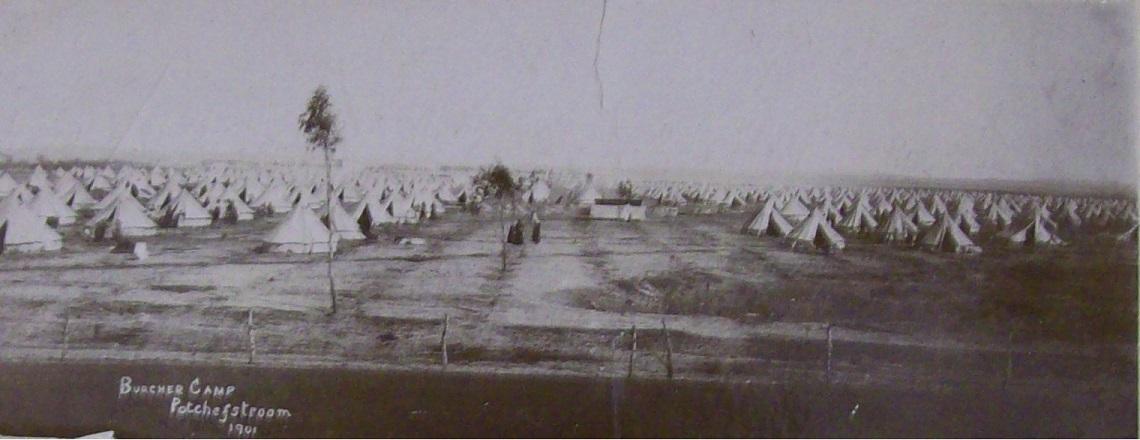

This photo of the second concentration camp was taken from the north. The stream in the foreground might have been the Mooi River or a furrow. The tree to the right can also be one that is still standing in the middle of the vlei bordered today by Govan Mbeki Drive (west and north) and Van der Hoff Park (south and east). (Potchefstroom Museum)

An area of about 15,5 hectare was occupied. The borders of this camp were the current Holtzhausen (N12), Landsberg, Buskus and Ben Pienaar Streets.

This was also divided into four sectors with two lanes of about 20m wide, crossing each other in the middle. On the one corner of this crossing were the rations warehouse, a soup kitchen and a communal oven. On the other corner was an apothecary tent and the quarters of the resident doctor. The quarters of the matrons and their staff was on another corner and four large class rooms were on the remaining corner. A road of about 30 m wide was made at the perimeter of the camp inside the fence. Each of the blocks so created had space for 300 bell tents.

The move progressed very orderly. For the new camp 200 new tents were made available. The first 100 tents were pitched and the people they were intended for, were relocated. As soon as their old tents were evacuated it was moved to the new camp where it was pitched and the next group was moved.

The cemetery of this camp was at the northeast of the camp where the Garden of Remembrance is today. The citation on the women’s monument in the camp states that a total of 1 141 people died in the two Potchefstroom camps, of which 967 were children. In the cemetery of the second concentration camp only 381 people were buried. The rest were buried in the Alexandra Park cemetery in town.

The wall of the Garden of Remembrance at the east end of Burger Street. This wall was built at the entrance to the camp cemetery in 1963, when the tombstones on the graves were removed and a cenotaph with the names of deceased erected.

After the visit of Emily Hobhouse to South Africa in December 1900 and her extensive tours to camps, she sent a report to the British government. This lead to the creation of a Ladies Committee with six independent members under the leadership of Mrs Millicent Fawcett. Mrs Fawcett visited the Potchefstroom camp from 29 September to 2 October 1901.

On the recommendation of the Ladies Committee the communal oven was installed and the soup kitchen created. Although the Ladies Committee did not support the Boer cause, they made recommendations which improved conditions in the camps.

Swart saw to many improvements in the new camp. He had the hospital tents replaced with four sturdy permanent structures. They were made from poplar poles, which were chopped off on the banks of the nearby Mooi River. The structure was covered in canvas with another piece of canvas stretched above the roof to help keep them cool.

Shortly after the move was completed, Swart was succeeded as superintendent by WK Tucker. This was probably due to the fact that Swart was often at logger heads with the authorities to urge them to improve circumstances in the camp.

Water was acquired from a furrow above the camp. In 1902 a pipe system was installed.

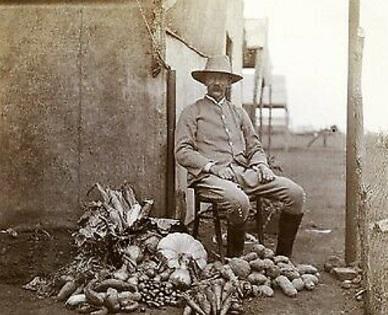

Mr Jacob Swart was the superintendent of the Potchefstroom concentration camp from February 1901. He encouraged inhabitants to make vegetable gardens and is here seen with some of the produce. At the first camp the vegetable garden was to the north of the camp. (LSE Library)

The proximity of the Mooi River meant a further improvement in conditions. In February 1902 an area, about 4,5 X 9m was partitioned off on the river bank to form a bathing pool where young women could regularly bath, a privilege that was not available at the old camp with its single furrow. Later two smaller bathing areas were built for the older women. The river also made the washing of clothes and bedding much easier.

The staff of the concentration camp in 1901. Back row: W Boardman (chief of police), JH van de Broeke (timekeeper) A Fancult (overseer garden), G Robertson (public prosecutor and sanitary inspector), M Lemmer (assistant to camp matron), EG Andersen (chief building department), R Hollow (assistant to camp matron), E Levin (chief storekeeper), E Rogers (assistant to relief matron), M Law (head education department), E Roth (clerk), F Roth (foreman camp), JJ Evans (transport conductor). Middle row: C Abbot (assistant to relief matron), A Garcia (nurse, town hospital), ASE Mitchell (matron, camp hospital), EJ Nash (relief matron), S Cromer (camp matron), J Swart (superintendent), M Rogers (matron, town hospital), Dr TJ Dixon (superintendent medical officer) MG Halkerk (matron, town hospital), DPG Walker (medical officer), EM Underwood (nurse, town hospital), C Peacock (nurse camp hospital). Front row: Dr JD Bird (medical officer), EA Whitehead (accountant), CJ Slade (assistant to superintendent), AB Pickard (in charge of camp stores), TG O’Hare (assistant dispenser) and C Wade (dispenser). The many references to “town hospital” are due to the fact that hospitals were set up in churches and houses in town. (Potchefstroom Museum)

A positive story

One of the inhabitants of the Potchefstroom camp was a Mrs Hester Swart, who was able to bring her ox-wagon with when she came to the Potchefstroom concentration camp. With the dire need of firewood, some women wanted to chop up the wagon for firewood. Mrs Swarts told them that she would rather chop them up if they dare to touch her wagon with an axe.

This wagon was quite special because it was used by the family of her husband in the Groot Trek from 1836 to 1838, as part of the group of Piet Retief. Its original owner was a Piet Swart and it was one of 3 000 wagons that were used to transport the itinerant farmers of the Eastern Cape to Natal, the Free State and the Transvaal during that migration. The wagon was also the only one still in existence that took part at the Battle of Bloedrivier on 16 December 1838.

In 1921 Mr JV (Boetie-Jan) Coetzee, then a history teacher at the Potchefstroom Gimnasium, endeavoured to buy the wagon and preserve it for posterity. He organised a tickey collection at the school and also involved students of the Potchefstroom University College. With this the sum of £2/7/6 (approximately R12) was collected, which was enough to buy the wagon.

This sounds like a lamentable attempt, but considering that there were 80 tickeys to a pound, more than 160 tickeys were so collected!

When Coetzee bought the wagon it was about to be turned into two smaller wagons. The wagon was then stored in the buildings of the old mill where the NWU Conservatory now stands. In 1924 it was shipped to the United Kingdom to represent South Africa at the Empire Exhibition held at Wembley and in 1938 it was taken to Bloedrivier for the unveiling of the monument there.

When the Potchefstroom Museum came into being in 1961, it was one of its prize exhibits and is still regarded as the most well-known artefact in possession of the Potchefstroom Museum.

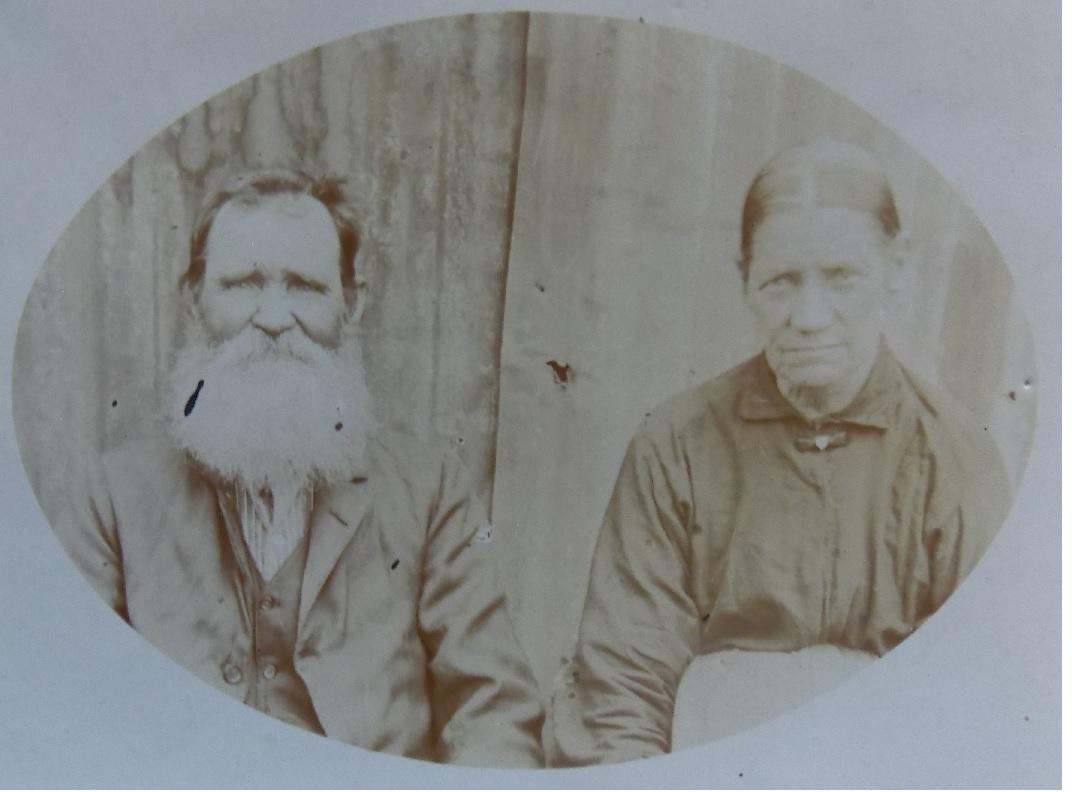

Piet Swart and his wife, Johanna Cornelia Swart, were the original owners of the Bloedrivier ox-wagon that was taken to the Potchefstroom concentration camp with his daughter-in-law Hester (Potchefstroom Museum)

This ox-wagon is known as the Bloedrivierwa, since it was one of the wagons at the Battle of Bloedrivier in 1838. It was nearly chopped up for firewood in the Potchefstroom concentration camp, but was saved and is now regarded as the most well-known artefact in possession of the Potchefstroom museum. (Lennie Gouws)

Closing of the camp

The signing of the peace treaty at the end of May 1902 did not mean the immediate closing down of the camp. It was repurposed as a transit camp for resettlement.

The 635 Bittereinders (Boers who fought to the “bitter end”) who laid down their weapons at Hartebeesfontein in June 1902 arrived at the camp to be reunited with their families, before they went back to their farms and houses.

Prisoners of war of the Western Transvaal commando that were repatriated from Cape Town and overseas used the Potchefstroom camp as a transit camp. Their arrival was met with much joy and tears. Subsequently the numbers at the camp rather increased than diminished.

In September 1902 there were 4 967 people in the camp of which 676 were newly arrived prisoners of war from India. Between June and September 5 014 left and in November a further 1 438. This left 2 070 in the camp and a further 296 men arrived. By this time the only inhabitants were families waiting for their men to arrive from the prisoner of war camps.

For Christmas 1902 each child in the camp received a small bag of sweets and an orange. The girls also received a little doll.

By the end of January 1903 only the Potchefstroom camp was still open in the Transvaal and it closed on 6 February when the last 167 persons departed.

Wagons were provided for the ride to their burned-down farms. Each family received food for one week and one of the tents that were previously regarded as unusable.

By the time the camp closed an orphanage was managed by female inhabitants of the camp in expectation of fathers arriving from overseas prisoner of war camps to be reunited with their children.

The group of orphans left behind was transferred to a government orphanage near the railway station and managed by a Miss Sharp. This lead to the establishment of an orphanage on a property to the east of the concentration camp. This later became the Potchefstroom Hoër Tegniese Skool that was founded in 1903.

It is generally regarded that the plight of the people in concentration camps for blacks was much worse than those in the so-called “white” concentration camps. A small one was founded in March 1901 on the Grimbeek farm, Elandsheuwel. It was one of the smallest and in September 1902 there were only 29 men, five women and five children in the camp.

It is an understatement to say that the concentration camps were one of the most tragic aspects of the war.

To the British the concentration camps were more than a military disappointment, it can be regarded as a military failure. It also became a socio-political fiasco.

Of everything that I have written over the years about the history of Potchefstroom, none has left me as emotional drained as the Potchefstroom concentration camp and the plight of its inhabitants. I can only repeat the inscription on the women’s monument. “Their memory must live forever.”

Main image: The first concentration camp of Potchefstroom was situated on the grounds of the later Potchefstroom High School for Boys. (Potchefstroom Museum)

About the author: Somewhere in her late teens Lennie realised that writing came easy to her and now, many decades later, she has written and co-written nine books on various aspects of the history of Potchefstroom. This is apart from various supplements and numerous articles, mostly published in the Potchefstroom Herald. Two of her books are available on amazon.com. One is a biography on Kenneth McArthur, Olympic gold medallist in the marathon of 1912. The other is an Afrikaans Christian novel. The supplement on the history of the Herald, at the time of its centenary in 2008, led to a Master’s degree in Communication Studies and one of the books, on NWU PUK Arts, led to a PhD in history. In the process of all this writing she has accumulated a large stash of information and photos on the history of Potchefstroom.

Principal sources:

- GN van den Bergh, Die Anglo-Boereoorlog in die Potchefstroom-omgewing, Christiaan de Wet-annale Nr. 11, 2013.

- GN van den Bergh, Die Potchefstroomse Konsentrasiekamp, Potchefstroom, 1999.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.