Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This article was prompted by my reading of a back number of the “Continental Modeller”, wherein there was a sparkling article entitled “Wanderings in the western Cape - South African scenes to inspire modelling”, which whetted my appetite to find out more.

The Inspiration

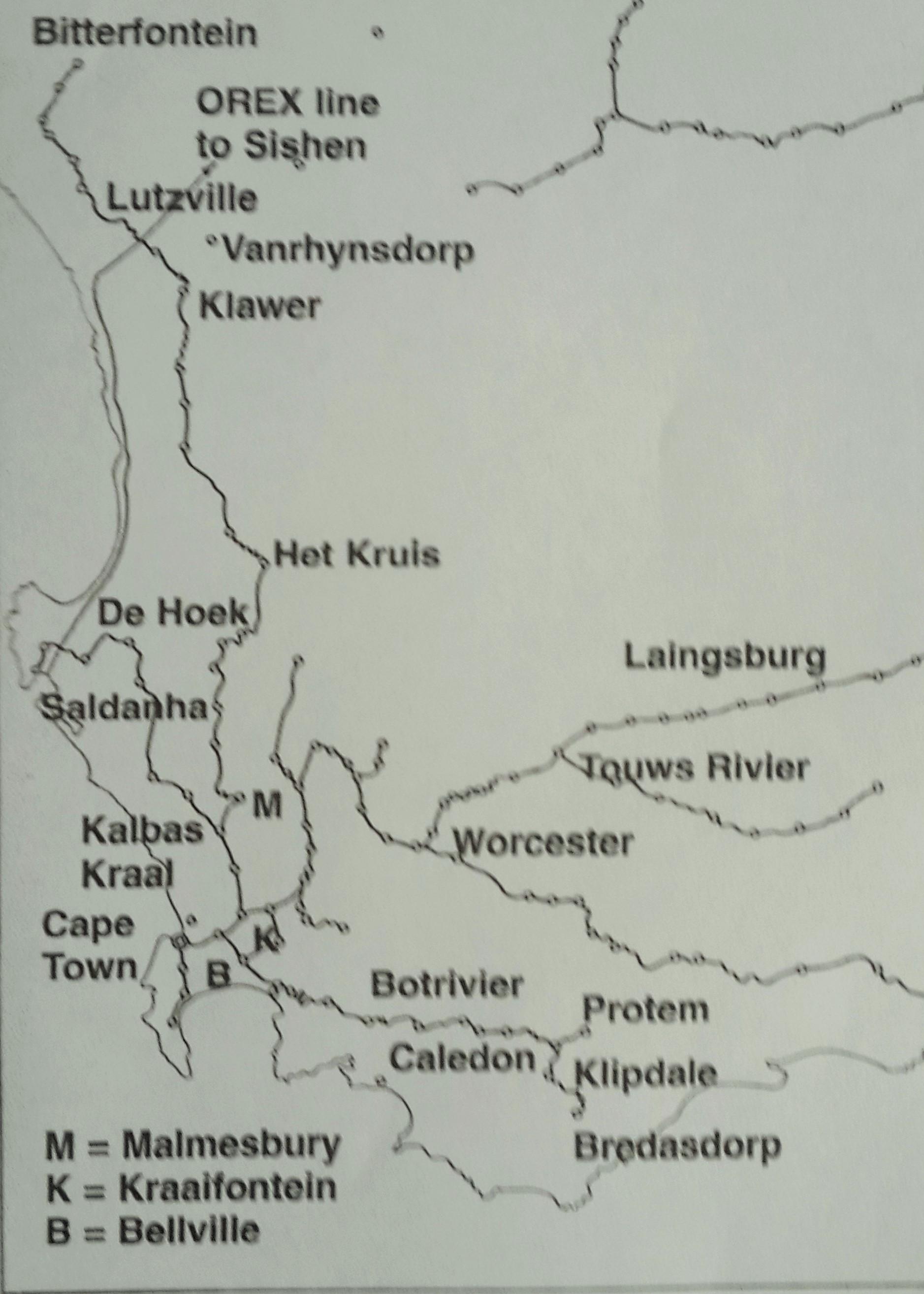

In my research I discovered a website with the title of “Soul of A Railway” by Les Pivnic and Charlie Lewis and what a find! The site is filled with classic photographs, explanatory text and maps of the highest quality by Bruno Martin. This effectively took the wind out of my sails as my intended topic had already been covered with great erudition. The old saying that a picture says a thousand words could not have been more apt and I implore the reader to delve into the “Soul of A Railway” website to appreciate our railway history which helped to mould South Africa into a modern state. Not to be disheartened I decided to go ahead nevertheless with my article to give some historical perspective to the branch lines of the Western Cape, that were laid down after the trunk routes had been completed.

At the dawn of the 20th century the Cape Government Railways (CGR) had linked their rails to most of the major towns in the Cape Colony and beyond by laying down what would become the main trunk routes across our land. The CGR had been organised into three divisions, namely the Western, Midland and Eastern, each one responsible for the building and then the running of the railways from the ports of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and East London respectively towards the hinterland. In the years between 1872 (when the CGR came into being) and 1897, the trunk routes from the coastal ports had reached Kimberley, by 1885 (the initial goal and a year before the Rand gold rush), then Bloemfontein (1890), Johannesburg followed (1892) and finally Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (1897).

As early as 1857 John (“Jock”) Paterson, of Port Elizabeth (and founder of the Standard Bank in 1862) was convinced that railways were the key to the future economic prosperity of the Cape Colony and its neighbours and at that time he drew up and published a map showing a network of proposed railway lines across the country, which bore an uncanny resemblance to the lines that were eventually built, the more remarkable was that neither diamonds nor gold had been discovered at the time (the prime motivation for the railways). Alas he did not live to see the fruition of his dream as he died at sea in 1880 in a shipwreck whilst returning to the Cape from England.

Map of Cape Railways (Continental Modeller)

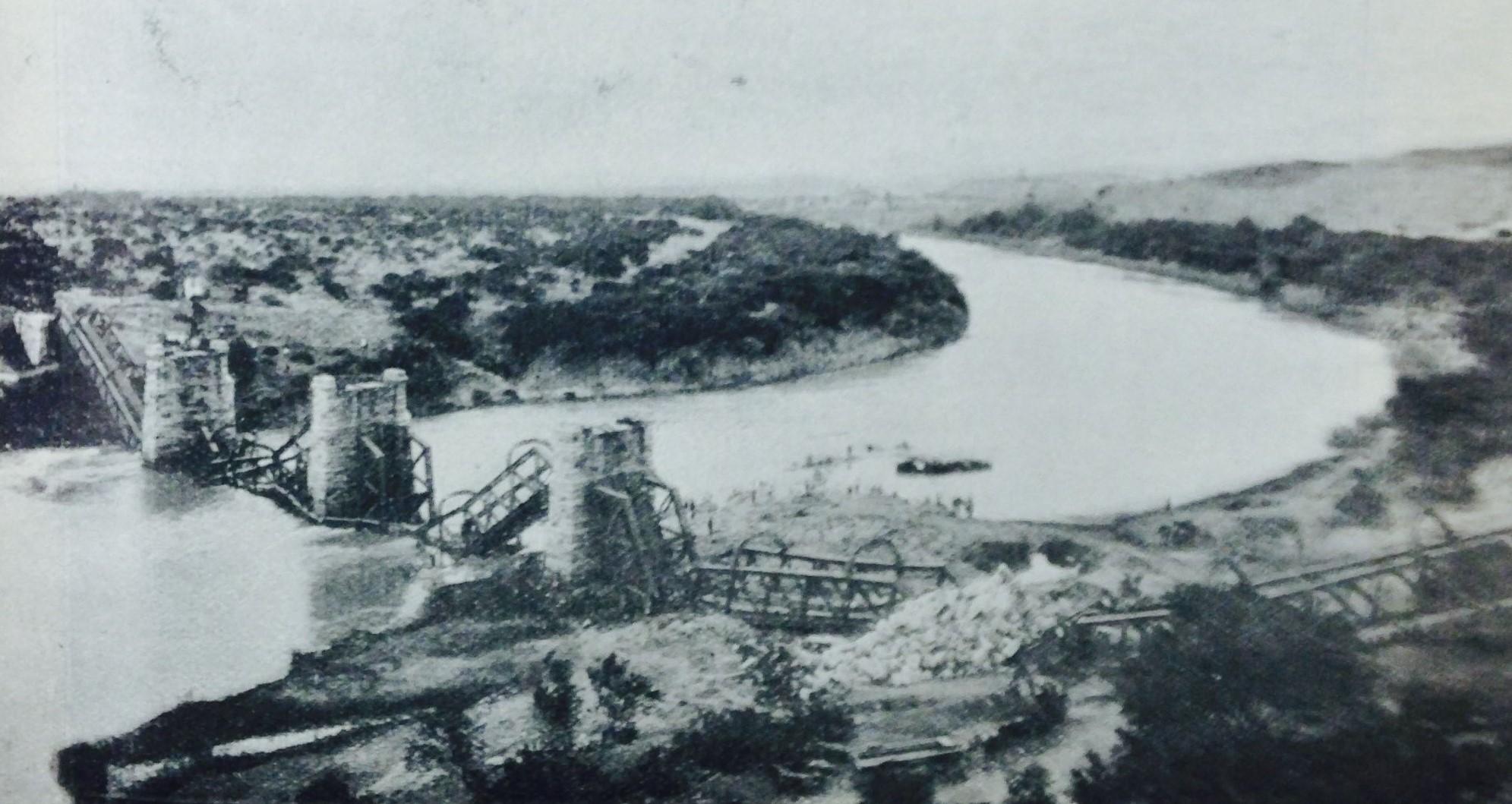

The Boer War (11th October 1899 to 31st May 1902) delayed several railway enterprises until after the “Peace of Vereeniging” was signed at Melrose House, Pretoria. Peacetime found a huge accumulation of equipment and supplies at the ports and the first priority was to clear the backlog by restoring the smooth operation of the various main lines. This was done by repairing the railway infrastructure which had been damaged by neglect, due to lack of maintenance and Boer sabotage during the war. Only after repairs had been carried out was it then possible to look to expand the railway network further.

A typical scene during the South African War (South African Railways Magazine)

The CGR was to last as a separate body until the 31st May 1910, whence it became an integral part of the new South African Railways (i.e. at the same time as the Act of Union). The CGR’s focus during the eight years between war’s end and Union was to provide secondary branch lines which would generate traffic from the farmlands to the north and east of Cape Town. The north was the easier prospect as no mountains were crossed, however to the east there was the barrier of the Hottentots Holland range to overcome in order to reach the Overberg beyond.

The important community of Malmesbury (proclaimed a town in 1829) was 50 miles (80 km) to the north of Cape Town and had already been reached by the railway on 12th November 1877, when the line, which branched of the main line at Kraaifontein, was built concurrently with the line between Wellington and Worcester (opened 16th June 1876). The works on both lines were carried out using the 3ft 6in (Cape) gauge instead of the 4ft 8½in (Standard) gauge previously used between Cape Town and Wellington; the change of gauge necessitated the inclusion of a third rail into Cape Town so as to avoid a break of gauge.

The Malmesbury branch could well have been the main line had it not been for the decision to extend towards Worcester from the railhead at Wellington and any future extension onward from Malmesbury would be run, in due course, northwards and not east.

The Act No. 40 of 1899 that was passed through the Cape Parliament, allowed a sum of £550 000 for an extension from Malmesbury to Pickenier’s Kloof; this line was completed as far as Moorreesburg by 9th September 1901 and still further to Eedenkuil by 15th November 1902. Whilst this was welcomed by the farmers of the Swartland it did not satisfy the farmers in the Hopefield region who clamoured for a line of their own to market their produce in Cape Town. The Hopefield Railway Committee predicted traffic amounting to 43 000 tons per annum, lobbied Parliament and were able to get a Bill passed for a railway under the Act No. 19 of 1900. The rub, however, was that the cost of the line should not exceed £135 000 and therefore a narrow gauge of 2ft 0in (610mm) was authorised. A survey was conducted (by April 1900) and it was concluded that the Hopefield line would branch off at Kalbas Kraal - the station before Malmesbury, where transhipment facilities were to be provided between narrow gauge and Cape gauge wagons. To ease the transfer between trucks, the tracks were laid at different heights so that the floors of the trucks were at the same level; even so the cost of transhipment was costly in both time and money. The line would purposely wind through the farmlands in order to serve the greatest area and would pass through Darling (reached by 4th October 1902) and eventually terminate at Hopefield (reached by 28th February 1903), a distance of 47 miles (76 km) with a prospective extension to Vredenburg and Saldanha Bay, should the line pay its way. An in depth study of the line can be read in the book entitled “24 Inches Apart” by Sydney Moir; suffice to say here that the line proved successful in serving the farming community, even if it did not always show an annual profit. Not only was it extended by February 1913 to Saldanha (Hoetjies Bay), but it was also converted to the 3ft 6in gauge by the 19th December 1926, when the first Cape gauge train steamed up the line.

Meanwhile the Malmesbury branch was being extended further northwards with the aim of reaching the Namaqualand copper mines at Springbok and O’okiep, however the line only ever reached as far as Bitterfontein, by 27th April 1927 and there it stopped, 400 miles (645 km) from Cape Town. For many years, the copper mines had used a narrow gauge (2ft 6in) railway to export their product, which ran north to Steinkopf and then west to the coast at Port Nolloth, from where it was shipped abroad. The line operated in its entirety from 1st January 1876 until sometime in 1945, when it was closed and sold off for scrap value. Water supply for the boilers of the steam engines was always a problem in the arid region and often there were times when the wagons were hauled by a team of mules for part of the journey, By the 1930’s the copper was being increasing sent southwards by road to the Bitterfontein railhead, where it was forwarded on by the SAR.

During the April of 1902 a trio of Boer delegates were given safe conduct to travel along the narrow gauge railway to Port Nolloth, for an onward voyage to Cape Town and then a journey by train up the Cape main line to Vereeniging, to parley with the British. The three were General Jan Smuts, his secretary (and brother-in-law) Petrus Krige and his “orderly” (and son of the Transvaal State Secretary) Deneys Reitz. Jan Smuts and his “Band of Burgers” had invaded the Cape Colony by crossing the Orange River at Kiba Drift on 3rd September 1901, in order to start an insurrection amongst the Cape Dutch and although there was some sympathy for the Boer cause, all they managed to do was to give the British forces the run around and had ended up attacking Springbok (a long way from Cape Town) a month or so before the war was over (with the signing of the “Peace of Vereeniging”). In any case the war was never about copper it was all about gold.

Loading up at Port Nolloth

The Overberg, beyond the Hottentots Holland Mountains was an area, stretching eastwards from the top of Sir Lowry’s Pass to Swellendam. The land had been settled by Free Burgers during the middle of the 18th century and they had developed a prosperous community farming wheat and sheep. Swellendam enjoyed its self-proclaimed independence (1795) for a brief time but when Britain took control of the Cape for the second time in 1806 they submitted to British rule. The British saw fit to improve communication between the Western Cape and the Overberg by building the Sir Lowrys’ Pass (so named after Lowry Cole the Governor of the Cape at the time). When opened on 6th July 1830 it replaced the old Hottentots Holland Kloof Pass, which was so severe that ox-wagons where dragged over with many being damaged in the process. Sir Lowry’s Pass is still the main road route (N2) leaving the Western Cape going towards the east and has been upgraded many times.

With the CGR committed to its trunk routes towards the interior it was left to a private company - the Cape Central Railways (CCR) to penetrate towards the Overberg, by building a branch line following the course of the Breede River coming down from Worcester, which went via Robertson and terminated at Roodewal (now known as Ashton) in 1887. This is where it stopped for several years while the CCR considered its next move; whether to go east to tap the Little Karoo or continue south eastwards towards Swellendam. As it was it did neither, because it went bust in 1892, having been undercut for the goods traffic by the transport riders with their ox-wagons. However within a short period of time a fresh railway company was floated, to be known as the New Central Cape Railway (NCCR) and its board of directors determined to head towards Mossel Bay with Swellendam being the first step.

Meanwhile the CGR had been tardy and had ignored the remonstrations of the people of Somerset West during the 1870’s for a railway to the foot of Sir Lowry’s Pass, but eventually their cries were heard and duly a branch line from Eerste River to the bottom of the Pass was opened by February 1890. Thus there were two railway routes that were heading in the general direction of Swellendam. As to which would get there first is well documented in the book entitled “Early Railways of the Cape” by that prolific writer Jose Burman. Really it was no contest as the NCCR had less distance to cover and had the easier route and won the race before the CGR had even got started. In any event the NCCR reached Swellendam by the 12th April 1899, three months before the planned extension by the NGR over Sir Lowry’s Pass to Caledon was begun on the 12th July 1899, the contract for which being awarded to George Pauling.

It would be another three months before war broke out between Boer and Brit on 11th October 1899. The war would severely restrict new railway building as labour, rolling stock and materials were to be commandeered by the Imperial Military Railways in order to aid the British War effort. Nevertheless construction over the Hottentot Holland Mountains commenced and George Pauling worked wonders with the limited resources at his disposal. The Caledon line would be officially opened to the public, two months after the ending of the war on 1st August 1902, although it had been used by the British army before that date for shipment to Cape Town of fodder for their horses.

George Pauling and his wife (Chronicles of a Contractor)

The coming of the railway was a boon for Caledon as the hot springs there (that had been visited since 1707), were to become highly fashionable and the thing to do was “to take the waters”. An extension onwards had always been contemplated but with the completion of the NCCR to Mossel Bay to link with the CGR coming down from George, it was no longer a high priority. In fact the CGR put it on the back burner and it was left to the SAR to extend as far as Protem in 1915, which was originally only intended to be a temporary terminus on route towards Swellendam, which was another 23 miles further on. Protem was given its name as an abbreviation of the Latin term Pro Tempore - for the time being, however the link to Swellendam was never to be completed and the only extension past the station was to be to the triangle, on which a locomotive could be turned around for the return journey. Bredersdorp, to the south of Protem, belatedly received its railway connection in 1924.

The story of the NCCR was of a well managed private railway, serving the communities of the Southern Cape between Worcester, Mossel Bay and George. It was never seriously under threat from the SAR (or its predecessor the CGR) and there was a good working relationship between the two concerns. There was always an option for the SAR to absorb the NCCR and this was only exercised in 1925, 15 years after the formation of the SAR.

The branch lines mentioned in this article were built to serve the rural communities of the Western Cape, over 100 years ago, when the railway was king and motorised transport was in its infancy. The arrival of the motor car and lorry along with the vast investment and consequent improvement of our road system made the under funded branch railways no longer a match for the road hauliers. Transnet Freight Rail the modern day custodians of our railway system whilst still wanting to retain ownership of the branch lines has invited tenders from the private sector to invest, run and maintain the branches in order to feed goods to their trunk routes. Having one’s cake and eating it comes to mind, maybe they should ask the Guptas.

Post Script: A previous article in History of South African Railways Series entitled “Streaks of Rust Across the Veld – The Demise of the Branch lines” tells the broader truth of the loss our heritage through the closure of the branch lines.

References and Further Reading

- “Wanderings in the western Cape” by Bill Longley-Cook, from the “Continental Modeller”, March 2008.

- "Soul of a Railway – System 1, Cape Western” from a web site by Les Pivnic and Charlie Lewis.

- “Early railways at the Cape” by Jose Burman.

- “24 inches Apart” by Sydney Moir.

- “Commando” by Deneys Reitz.

- “Chronicles of a Contractor” by George Pauling.

- “A Century of Transport 1860 to 1960” Part 1 by A. Van Lingen.

- “South African Steam Today” (as of 1980) by David C. Rogers.

- “The Great Steam Trek” C.P. Lewis and A.A. Jorgensen.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.