Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

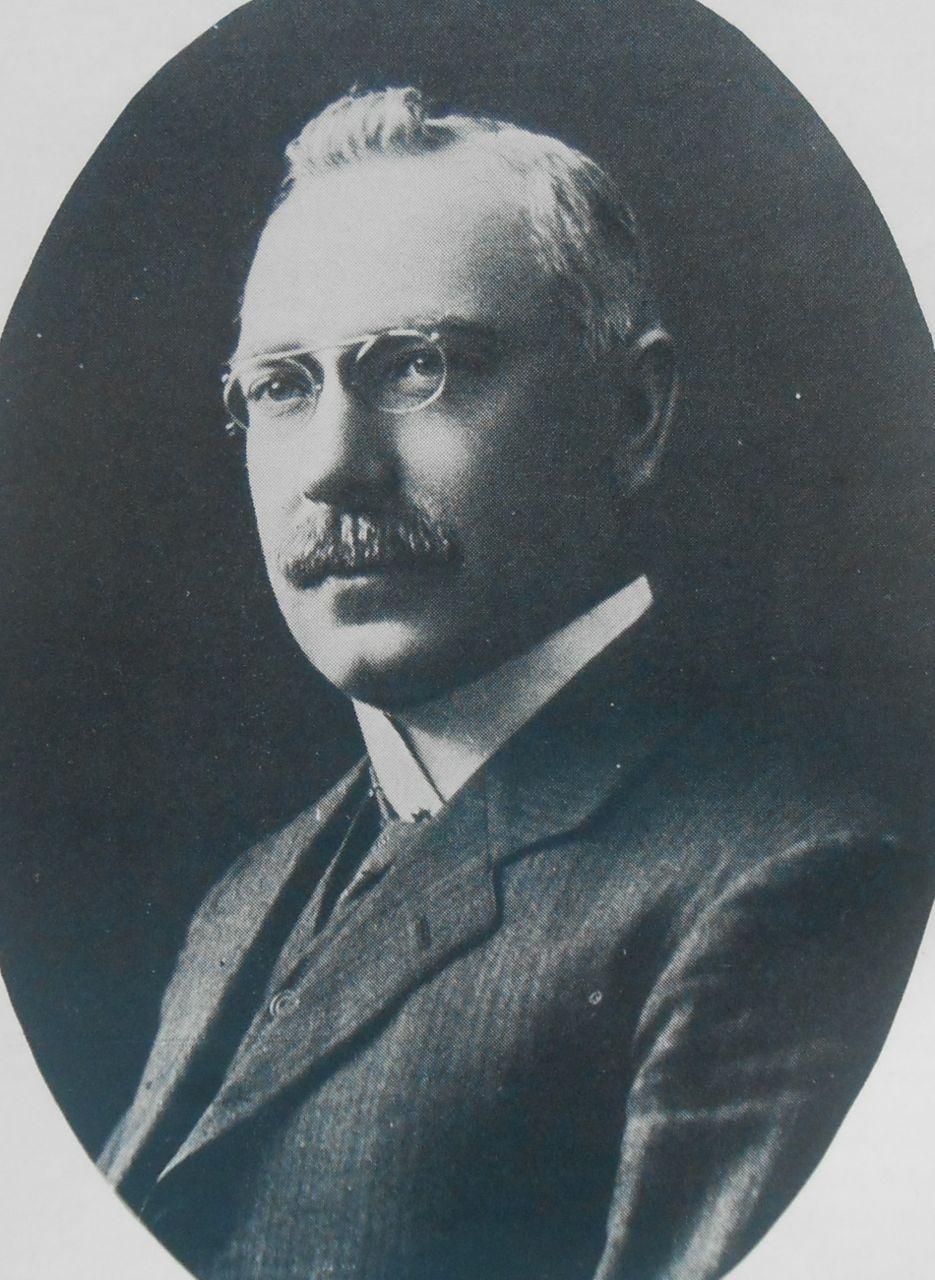

In 1884, before Johannesburg ever existed and when herds of game still roamed free across the savannah, a young man left his home in the Eastern Cape in search of adventure in what was then the Eastern Transvaal (now known as Mpumalanga). His name was Percy Fitzpatrick (1862-1931) and he went hoping to find his fortune on the newly proclaimed goldfields. He, like so many others found nothing but disappointment but far from being downhearted he responded by making a living as a transport rider carrying supplies in an ox-wagon from Delagoa Bay (present day Maputo) to the goldfields of Barberton and Pilgrims Rest. It was tough going as the journey to and from the goldfields was through fever ridden bushveld, along rough trails on which the ox-wagons, travelling in convoy, rumbled along at the pace of the Ox. Each wagon had a team of 12 to 16 oxen and because of the heat during the day they travelled in two four hour shifts, the first before sunrise and the second after sunset. Seldom would they travel more than 20 miles (32 km) in a day and at the end of each shift the wagons were out-spanned, when men and oxen rested before it was time for the next shift.

“Outspan" – a sketch by Charles Bell, 1880 (Parliamentary Library)

Later in life Fitzpatrick would write down his reminiscences of his time spent in the Lowveld in his book for children, entitled “Jock of the Bushveld”, which was a distillation of bedtime stories that he had told to his own children, with the main character of the book being his faithful companion, a dog called Jock (a bull terrier). The book has become a classic which tells of a time and a way of life now long past.

Book Cover

During his lifetime, Fitzpatrick saw great advances in modes of transportation from the ox-wagon to the iron horse and then on to the motor vehicle, advances hastened not only by modern science but also by the demands of mining and industrialisation in the region known as the Rand (a shorter rendering of Witwatersrand).

The Witwatersrand (Ridge of White Waters), was situated in the South African Republic, 50 miles north of the Vaal river and it was there in early 1886 that gold was discovered in an outcrop of conglomerate rock (which became known as the Main Reef). This discovery would set in motion the greatest Gold Rush ever seen and there was an immediate need for better means to get there. Of course that was easier said than done and in the short term the ox-wagon was the only form of transport for the conveyance of heavy goods, until such time the railway lines could be extended from the existing railheads of Colesberg and Ladysmith (click here to read “Race for the Rand”). The rail head at Kimberley seemed the most logical place from which to extend the railway coming up from the Cape, but ideological differences between the South African Republic (a.k.a. Transvaal) and the Cape Colony (read Paul Kruger and Cecil Rhodes) precluded it being so. The first train to enter Park Station, Johannesburg, from Cape Town, arrived on 15th September 1892, having travelled via De Aar and Bloemfontein.

The Rand would become a belt of mining activity extending for a distance of 60 miles (96 km) on an east-west axis and at its heart was the boomtown of Johannesburg which in a mere five years had gone from a mining camp to a metropolis to rival Kimberley.

Had the Gold Rush been south of the Vaal river, instead of north, it is likely that history would have panned out far differently. Just suppose for a moment that the Northern Free State goldfields had been discovered first, the distance from Kimberley to Welkom would have been 125 miles instead of the 300 miles to Johannesburg. Logistics would have been far easier and at the time the Cape and the Free State were on good terms with each other, so it is highly likely that events would have been more amicable, that is to say no Boer War; however that “What If?” scenario is for another debate.

We cannot change our history and South Africa has developed with the mainstay of its economy well inland away from its harbours. There being no navigable rivers into the interior the railways and roads had to be the corridors by which access was gained to the interior – a high plateau over 5000 feet (1524 m) above sea level.

On the formation of the Union of South Africa (31 May 1910) it was made possible to implement a single policy with regard to the co-ordination of transport affairs for the benefit of economic growth and as a first priority the amalgamation of the former colonial government railways into the South African Railways (SAR) under the able administration of William Hoy (later to become Sir William) was concluded. Hoy was a progressive and saw the potential of the motor vehicle, powered by the internal combustion engine, as a means to provide feeder services to railheads, as a cheaper alternative to extending branch lines further into the country districts. Although he was lobbied to provide a branch line to the fishing village of Hermanus(petriesfontein), he never gave his permission as he felt a bus service (started in 1912) from Botrivier station would suffice. He also had an ulterior motive as he did not want to see day trippers from Cape Town, arriving in droves, overcrowding his favourite getaway spot; he was to retire there and was fondly known as “The Laird”, referring to his Scottish birth. I wonder what he would say if he could see it now?

William Hoy (Railways Magazine 1979)

Bot River to Hermanus Bus from “Hermanus” by Jose Burman

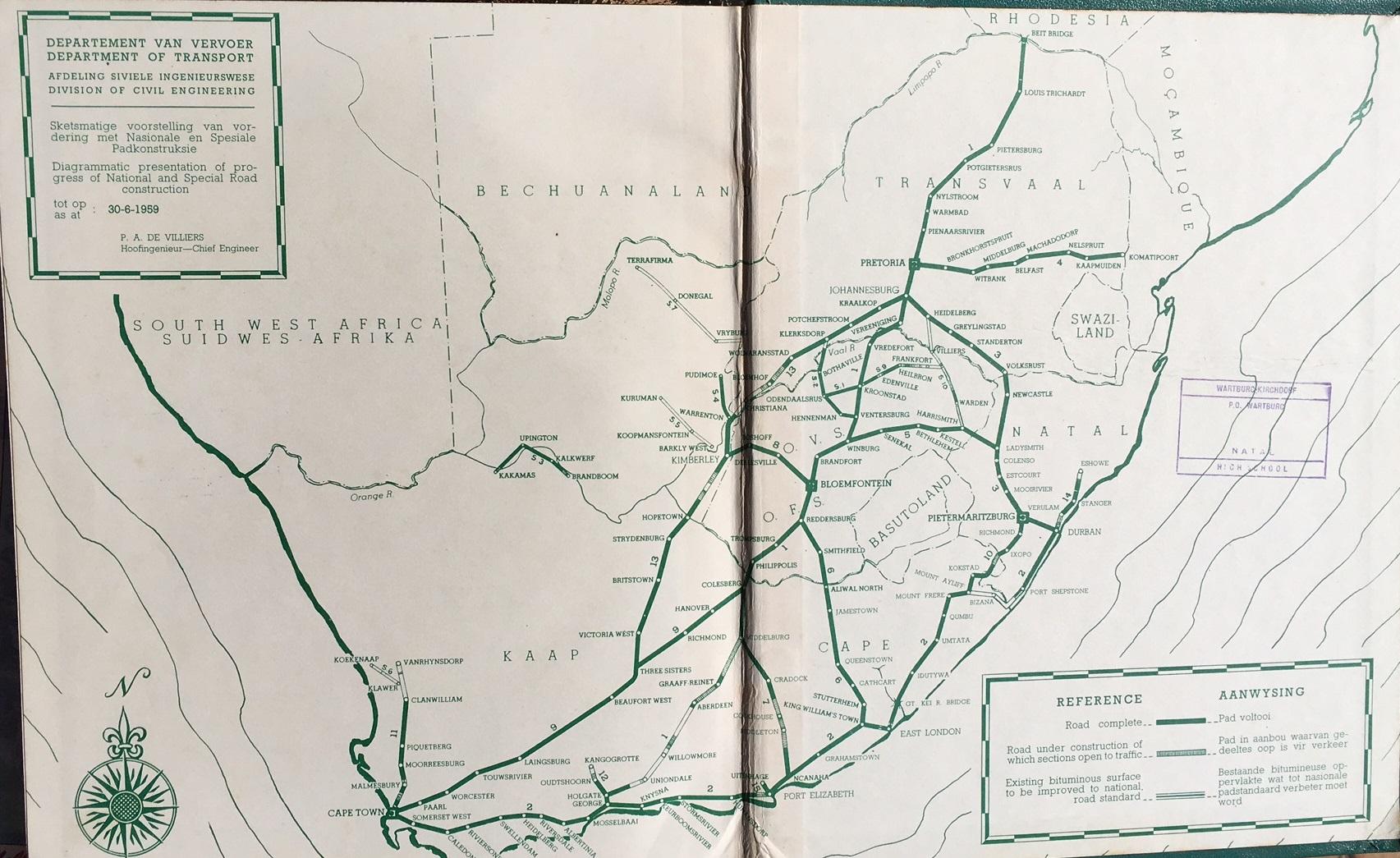

In the first twenty-five years of the Union (up to 1935) the SAR came to dominate the transport scene with control over railways, harbours, aviation and road motor transport. The year of 1935 was important in that the National Road Act (Act No.42 of 1935) was passed. By this Act was created a National Road Fund, the revenue for which was collected from a thrupence (3d) per gallon duty on petrol. A National Road Board was put in place to administer the Fund and this body was made responsible for planning and financing the construction and maintenance of arterial roads of national importance. However before road construction could get into full swing the Second World War intervened and its duration of nearly six years (1939-1945) would halt large scale road building until the end of hostilities. However there were two notable exceptions in the Du Toit’s Kloof Pass (connecting Paarl with Worcester) and the Outeniqua Pass (connecting George to the Little Karoo), which were built initially by Italian prisoners of war (with their full consent on participation); it therefore could be said (tongue in check) that the passes were built by the Romans. The war would end before completion and the POW’s were repatriated and thereafter local labour employed to finish the work. Both passes would open for traffic in 1951 with the Du Toit’s Kloof Pass superseding the Bain’s Kloof Pass as part of the Great North Road and the Outeniqua Pass superseding the Montagu Pass, whilst both the superseded passes remained open to local traffic. The Du Toit’s Kloof Pass was in turn superseded in 1988 when the Huguenot Tunnel was opened; the tunnel through the mountain, which allows one lane of traffic in each direction, is nearly four kilometres long and is the longest road tunnel in South Africa

Department of Transport Map from 1959

With the return of peacetime and with the necessary resources (money, men and materials) in place, work was resumed on the National Road network which would link the major towns and cities of the nation via the smaller “dorps” in between. This strategy was deemed adequate during the 1950’s as the bulk of heavy goods traffic was still carried by the railways, however, as the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s rolled by, road haulage was starting to compete strongly with the railway.

With road haulage (logistics) coming to the fore the National Roads were re-routed in order to by-pass the towns so that heavy vehicles avoided the urban areas; this was to be a blessing and a curse for the “dorp” as it meant that on the one hand traffic no longer flowed down its main street endangering the townsfolk, however on the other hand the passing trade was doing just that and local businesses suffered as a result. Philippolis, the oldest town (originally a mission station) in the Free State, once had three petrol stations; it now has only the one. Originally on the N1 route between Colesberg and Bloemfontein it is now by-passed with the old road classified as the R717; a road less travelled but still worthwhile as heavy trucks are absent.

There are plans afoot to upgrade the De Beers Pass (between Ladysmith and Harrismith), which, if it ever goes ahead, will by-pass Van Reenen and Harrismith. This possible new route for the N3 would follow a more gradual ascent up the escarpment to the Highveld, which would benefit the drivers of the heavy lorries that ply between Durban and Johannesburg, but it would conversely be to the detriment of all those who earn a living in Harrismith, who are dependent on passing trade. I always make a pit stop there to refuel and have a “Wimpy” breakfast; it has become a tradition on my holiday trips to the coast.

The N4 route eastwards from Pretoria goes to the border post at Komatipoort and thence onward to Maputo and its harbour in Delagoa Bay. The N4 highway closely follows the railway line that pre-dates it; the railway having been built in the days of Paul Kruger and officially opened on the 8th July 1895 (although in use prior to that date), in order to provide an independent outlet to the sea which avoided using the ports of the British colonies of the Cape and Natal. The Transvaal’s independence was to be short lived (1881-1900) and by mid-1900 the British had occupied Pretoria and had taken control of the railways of the Transvaal (NZASM), but not in time to prevent Oom Paul from slipping over the border into neutral Mozambique and onto a Dutch warship in Delagoa Bay which weighed anchor on 20th October 1900, setting sail for Europe. He would go into exile never to see Africa again.

Medallion commemorating opening of Delagoa Bay railway festivities

Delagoa Bay is a natural harbour (first known to the Portuguese fleets in the 16th century) which has the benefit of being the closest port to province of Gauteng (previously known as the region of Pretoria/Witwatersrand/Vereeniging); the financial, commercial and industrial hub of South Africa. The N4 corridor shared by road and rail from Gauteng to Maputo is becoming increasingly more important as an alternative to the N3 corridor between Gauteng and Durban, as witnessed by the increase in traffic volumes over the last 30 years which has necessitated much of the route being upgraded to dual carriageway especially on the Highveld section as far as Belfast.

With all the heavy duty vehicles (HDV’s) now trundling down our highways, Sir Percy Fitzpatrick would be aghast if he could see a double articulated side tipping rig (gross mass of 56 tons) travelling towards him at 80 kph (50 mph). Time is nigh that all heavy loads should to be transferred back to the railways; all those in favour say “Aye”.

Side view of side tipping rig (AFRIT)

References and further reading:

- “Jock of the Bushveld” by Sir Percy Fitzpatrick first published 1907.

- “Towards the Far Horizon, the story of the Ox-wagon in South Africa” by Jose Burman, Human & Rousseau, 1988.

- “Hermanus” by Jose Burman, Human & Rousseau, 1989.

- “A Brief History of Roads in South Africa - In the Beginning” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal. 2017.

- “A brief history of transport infrastructure in South Africa up to the end of the 20th century – Chapter 3: the first roads – building the foundation for a country-wide road network” by Dr. Malcolm Mitchell, “Civil Engineering” magazine, April 2014, published by the SAICE.

- “The History of National Roads in South Africa” by Bernal C. Floor, CTP Book Printers 1985.

- “A Century of Transport, 1860-1960”, by De Gama Publications, 1960.

- “National Roads of the Past” by R.A.F. Smith, The Civil Engineer in South Africa, September 1973.

- “Shell Road Map of South Africa” (fold-out) circa 1965 with distances in miles.

- “The Romance of Cape Mountain Passes” by Graham Ross, published by David Philip.

- “Drakensberg Passes” by Gillis van Schalkwyk.

- N3 Toll Concession web site: www.n3tc.co.za

- N4 (Maputo) Corridor web site: www.tracn4.co.za

- The South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) web site: www.nra.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.