Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

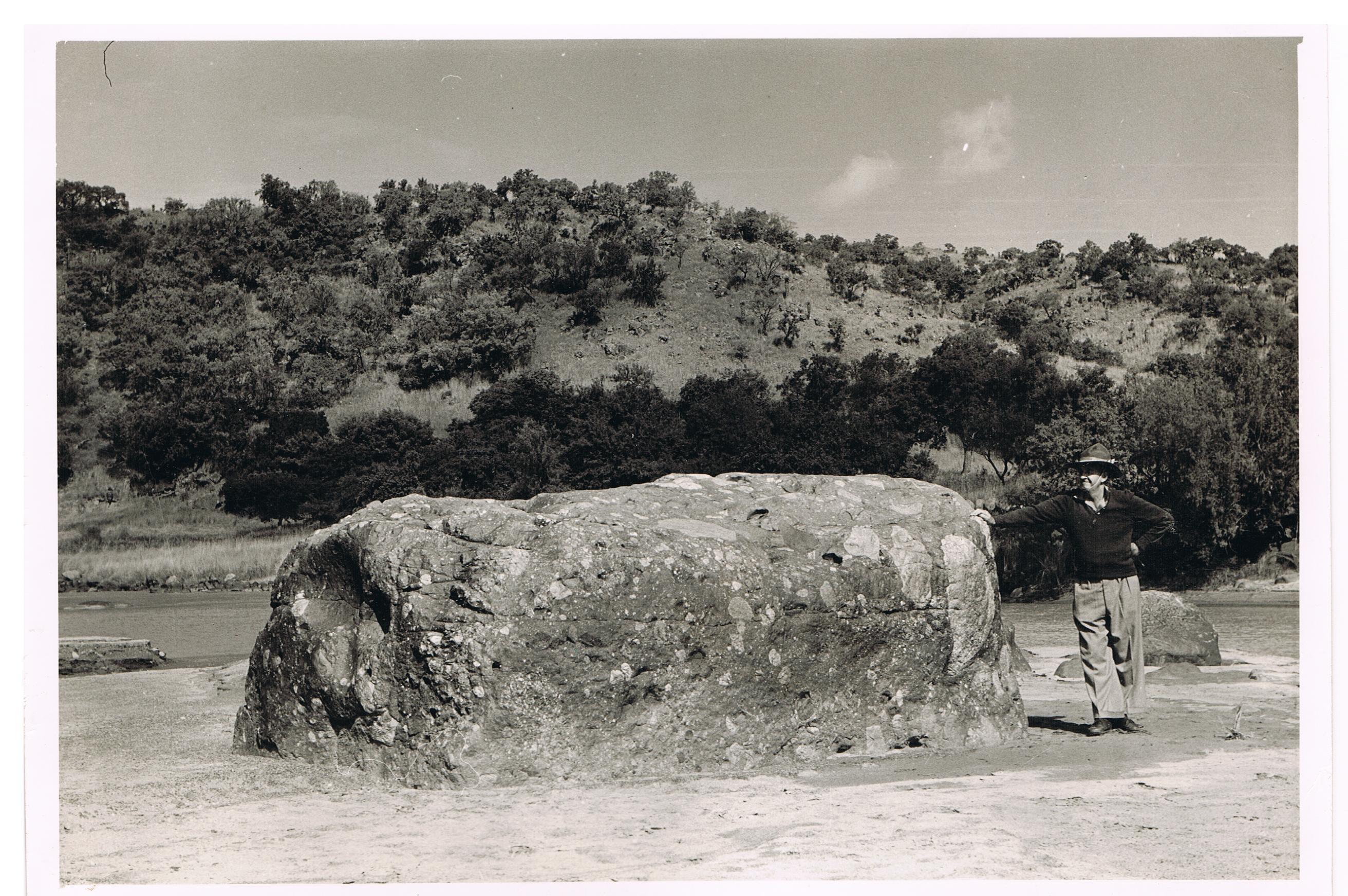

Sotondose’s Drift on the Buffalo River is not really a drift at all. Situated at the bottom end of an upside-down triangle with Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift comprising the other angles, access is down very steep rocky hillsides on either flank. At low water it consists of a difficult boulder-hopping crossing for foot traffic only. It is marked by a curiously shaped so-called “coffin rock’.

Coffin Rock (Talana Museum)

A couple of hundred yards upstream there is a large flat deep-water pool which is easily swimmable. That is, if one can swim in the first place, and is not dragged down by heavy clothing or equipment. I have always crossed the river here with my tour groups after a hot-and-sticky hike over the eight miles of the Fugitive’s Trail. Of course, we also took the precaution of rigging a lifeline across the river and had a Zodiac with an outboard motor and life jackets in case any person either got into difficulties or preferred a ride.

Curiously enough, there is also another large rock in the middle of this pool which, at full water level, also protrudes like a coffin. Readers who have watched “Zulu Dawn” will recognize the spot as where Lieutenant Vereker, lying pinned under his horse, makes a miraculous shot at a Zulu, triumphantly carrying off the Queen’s Colour, on the opposite bluff. A little poetic licence, of course. Vereker was already dead, killed at Isandlwana, and the Colour was lost in the river.

The pool is quite safe. If one gets into trouble, all one has to do is lie on one’s back and allow the strong eddy to deposit you back onto the bank.

I have white-water rafted this stretch of river, and can vouch to the strength of the current at high water and the degree of difficulty. You can’t do this at low water – you simply spend all your time dragging your canoe over rocks.

IF you survived Isandlwana and IF you got out before the Zulu “horns” closed around the mountain, your first choice of refuge would have been the British garrison at Rorke’s Drift. If you left it too late, then you would have had to run the gauntlet along the line of least resistance through the gap between the two “horns”. Which would lead you, whether you liked it or not, to Sotondose’s Drift. But you first had to make it over the Buffalo River before reaching the perceived safety of the Natal bank.

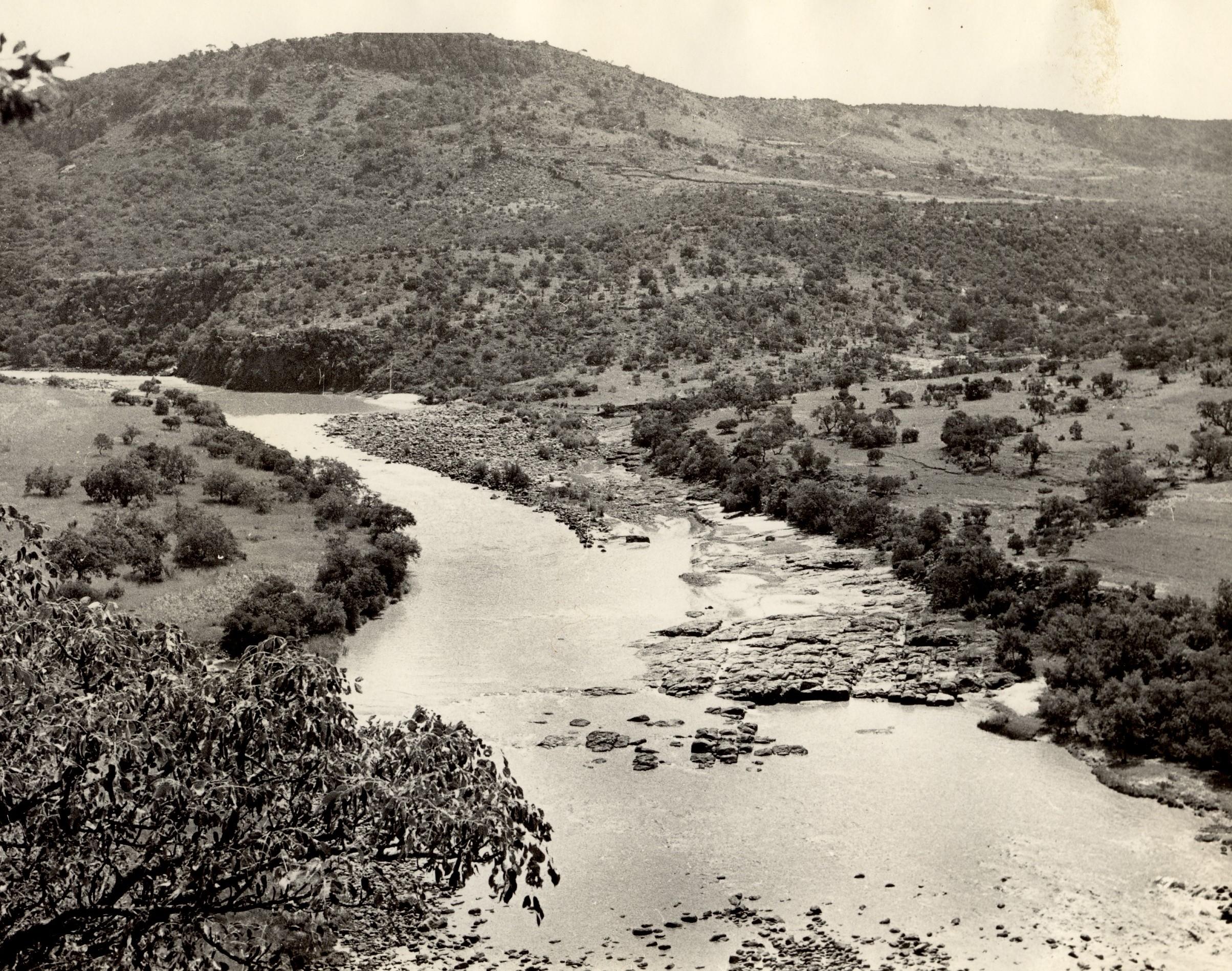

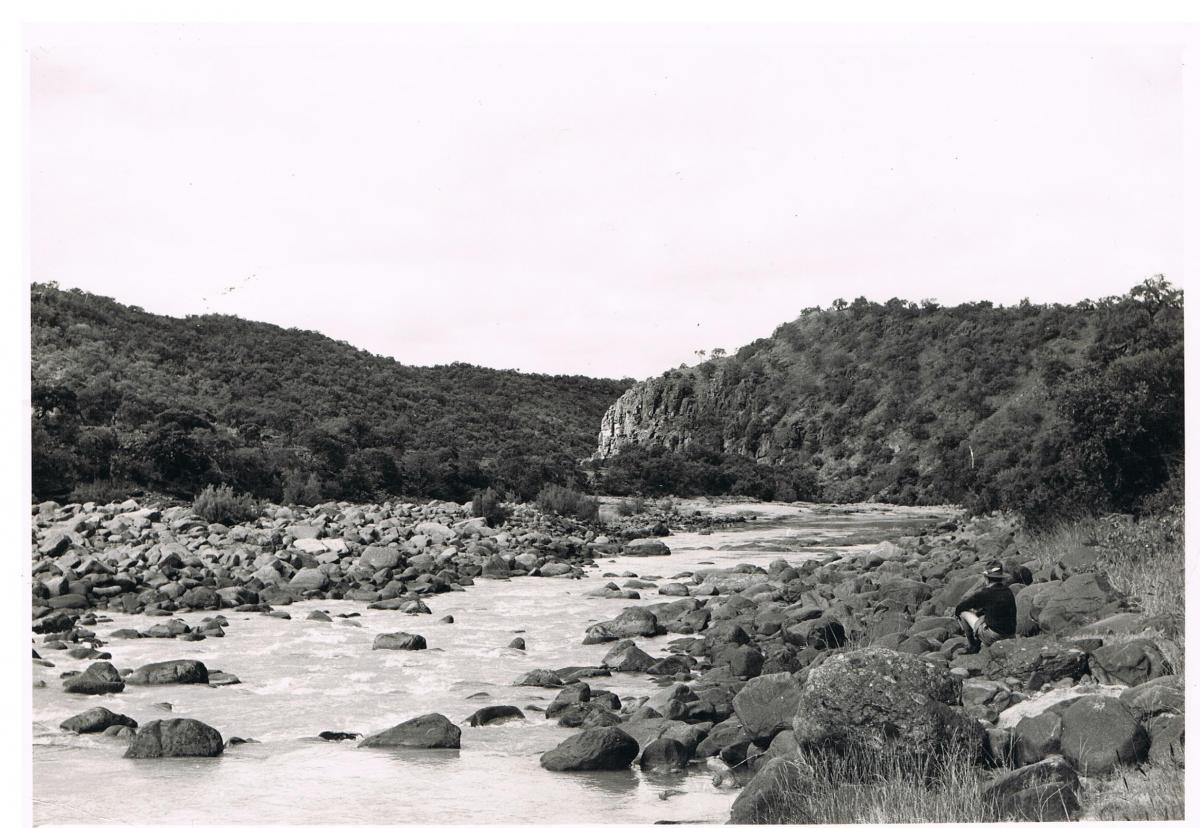

Buffalo River (Talana Museum)

Accounts from members of the column that visited Isandlwana in May 1879 to recover wagons and to make a start at burying the remnants of the dead, estimate that nearly 70% of the British casualties were killed along this escape route, indicating that Isandlwana had turned into a rout.

Lieutenant Horace Smith-Dorrien described the scene at Isandlwana as “utter confusion”, both British and Zulu, “all in a struggling mass, making through the camp towards the road, where the Zulus had already closed the way of escape. The ground there down to the river was so broken that the Zulus went as fast as the horses, killing all the way”

This became known as the Fugitive’s Trail towards Sotondose’s Drift. Note, not “Survivor’s Trail” or “Escaper’s Trail. This reflected the view at that time that most of these men could be considered cowardly or deserters and should have stayed at Isandlwana to die painfully and uselessly in a glorious last stand instead.

And since no-one could pronounce Sotondose’s Drift, it became known as Fugitive’s Drift.

Buffalo River towards Fugitives Drift (Talana Museum)

The tale of hardships suffered by escaping British and Colonial troops along the Fugitive’s Trail is, for me, more harrowing than the pitched battle of Isandlwana. Exhausted, ammunition spent, their will to survive drove them on over impossibly rough terrain, all the while being hunted and picked off like wild game, to die lonely and terrible deaths all along the trail. Not one single foot soldier made it - you had to have a horse. Members of the Natal Native Contingent could discard their European trappings and blend in. European troops in red jackets had no hope of concealment in summer’s greenery.

If you were able to avoid the marsh along the way, you would have arrived on the bluffs overlooking the river, and made your way as carefully as possible down the few footpaths towards the Drift, all the while being harried by Zulus. Adrenaline would have long since been spent – you would have been stumbling along on automatic, only your will to survive keeping you going.

Along the Fugitive's Trail (Talana Museum)

On reaching the water, most survivors would have been faced with an impossible choice. The river was flowing strongly and the rocks signposting the Drift submerged. Behind you are more and more chanting, screaming Zulu warriors picking their way down the slopes. In front of you, almost certain death by drowning because very few could swim. Those who still had their horses could perhaps cling to the saddle and trust that the animal would get them across. But you have to try. Otherwise you’d simply be picked off at leisure.

There are two bright spots in the whole whirling, swirling fiasco at Fugitive’s Drift. The first is the attempt to get the Queen’s Colour of the 1st Battalion 24th Regiment across the river and out of the hands of the Zulus by Lieutenant Teignmouth Melvill, Adjutant of the 1st Battalion. The other is the Victoria Cross awarded to Private Wassall (80th Regiment) of the Mounted Infantry contingent for saving his mate, Private Westwood, from drowning in the river.

Every Regiment is highly sensitive about its’ Colours. The 24th even more so. The Regiment had already lost two - one thrown overboard off the Cape to prevent it being taken by a Dutch warship, and the second at the battle of Chilianwhalla in 1849, when a soldier who had picked it up and wrapped it around his body had been killed and buried without anyone being aware of what he was carrying. Melvill was determined that there would not be another such incident.

Lieutenant Neville Curling RA, who gave evidence at the Court of Enquiry held at Helpmekaar on 27th January, indicated that after losing the two remaining guns of N5 battery, Curling became one of the fugitives. 'I was passed by Lieutenant Coghill of the 24th, wearing a blue patrol jacket and cord breeches, and riding a roan horse. When approaching Fugitives' Drift, and at least half a mile behind Coghill, Lieutenant Melvile (sic) of the 24th, in a red coat, with a cased colour across the front of his saddle, passed me going to the Drift. Near the river I saw Lieutenant Melville (sic) with a colour, the staff being broken”

Melvill and Coghill reached the drift together with Lieutenant Walter Robert Higginson (l/3rd N.N.C.) who remembered –

I put my horse in behind Mr Cochrane’s but he made a bad attempt at swimming and getting on a big stone in the middle of the river, he turned over and threw me off and I sank at once, as I had my rifle and ammunition with me, but on dropping them I managed better. The current carried me downstream a good distance but I fortunately came on a large rock which I held on to; getting the water out of my eyes I looked round and saw a nigger boy mounting my horse on this side; I called out for someone to stop him, but no one took any notice of me;

Poor Melvill was also thrown; He held on tightly to the Queen's Colour, which he had taken from the field of battle when all was over, and as he came down towards me he called out to me to catch hold of the pole. I did so and the force with which the current was running dragged me off the rock to which I clung but fortunately into still water. Coghill, who had got his horse over all right, came riding back down the bank to help Melville (sic), and as he put his horse in, close to us, the Zulus who were 25 yards from us on the other bank commenced firing at us in the water. Almost the first shot killed Coghill's horse, and on his getting clear of him we started for the bank and managed to get out all right. When we had got about 100 yards up the bank two Zulus came after us; when they were within 30 yards Melville & Coghill fired and killed them both. I was without arms of any kind having lost my rifle and ammunition in the river, and I had no revolver.

When we had gone a few yards further Melvill said he could go no further and Coghill said the same. When they stopped, I pushed on reaching the top of the hill. I found four Basuto with whom I escaped by holding on to a horse's tail. I got into Helpmekaar as soon as possible. As I got there early in the morning I at once proceeded to Rorke’s Drift, and reported myself to Comd’t Lonsdale’.

James Brickhill, a Colonial employed as an Interpreter, largely confirmed Higginson’s version of Melvill’s demise;-

Reaching the Buffalo we found it rolling high. No time for choosing the best crossing then. There were Zulus in running lines making for the stiller water higher up. My horse plunged in, swimming at once, but had scarcely gone six yards before he stumbled over something large and I nearly fell into the rushing stream beyond. I clutched at his mane and guided his rein with care, and yet four times I thought that all was lost. Not ten yards below was a waterfall, in the seething pool of which three riderless horses were swishing round and round. Mr Melvill had crossed a little higher up, Mr Foley immediately behind him. Mr M’s horse seemed to have some difficulty in getting up the bank this side. Our impulse was to go to his assistance, but his horse gave a plunge and I thought was climbing out’.

Some two weeks later, on 04 February, a patrol was sent from Rorkes to Fugitives to look for the missing Colours. Lieutenant Henry Harford, a British officer who was literally worth his weight in gold as he was also a fluent Zulu linguist, and who wrote an extremely entertaining Diary of his experiences, accompanied a party led by Major Black. His account of the expeditions recalls -

... and as there was still sufficient of the afternoon left, Major Black suggested that we should go a little further down, ... when suddenly just off the track to the right of us, we saw two bodies, and on going to have a look at them found that they were those of Lieutenant Melville (sic) and Coghill. Both of them were clearly recognisable. Melville was in red, and Coghill in blue uniform, both were lying on their backs about a yard from each other. Melville at right angles to the path and Coghill parallel with it, a little above Melville and with his head uphill, both assegaied but otherwise untouched.

Coghill and Melvill Memorial (Talana Museum)

However, the patrol could not find the Colour. They continued the search the following day, and the Colour pole was spotted, sticking up out of a rock pole where it had snagged. The Colour was taken back to Rorke’s Drift, where the whole garrison turned out and it was met there by a guard of honour. Then the Colour was carried to Helpmekaar, and Harford, who had found it, was privileged to be standard bearer: a unique occasion, in that an officer of another regiment (the 99th) carried the Queen's Colour of the 24th. When the Colour returned to England with the 24th Regiment, Queen Victoria crowned it with a wreath of Immortelles.

The question was mooted as to whether Melvill and Coghill should be awarded a Victoria Cross? However, the Royal Warrant at this time decreed that one had to be alive in order to be awarded a Victoria Cross. There was no provision for posthumous awards.

Lord Chelmsford ducked the issue by maintaining that the question did not arise as they were both dead. Sir Garnet Wolseley was even more vociferous, maintaining that the two officers should have remained with their men.

However, largely as a result of all the gallant acts of the Boer War, which would have gone unrewarded simply because the perpetrator had given his life for Queen and country at the same time, provision was made for posthumous awards in 1902 and confirmed in 1907. One of the first in line for such an award was Melvill, together with Lt. Coghill who accompanied him the last part of the way and was also killed.

David Ratray carrying the cross to grave of Lts Coghill and Melvill (Talana Museum)

Before we move off the Melvill and Coghill story, and if Lieutenant Higginson is to be believed, then their memorial is in the wrong place. It stands three quarters of the way up a very steep slope, easily half a mile or more from the river. Allegedly buried at the site where they were killed, it is definitely NOT just over 100 yards away from the river. Secondly, the reason that Chelmsford had left Coghill behind in camp that morning was that he was incapacitated with a wrenched knee. Having suffered the same injury while playing rugby, there is no way he could have made it so far up the slope before he was killed. One is forced to conjecture whether Melvill might have made it out of there had Coghill not slowed him down.

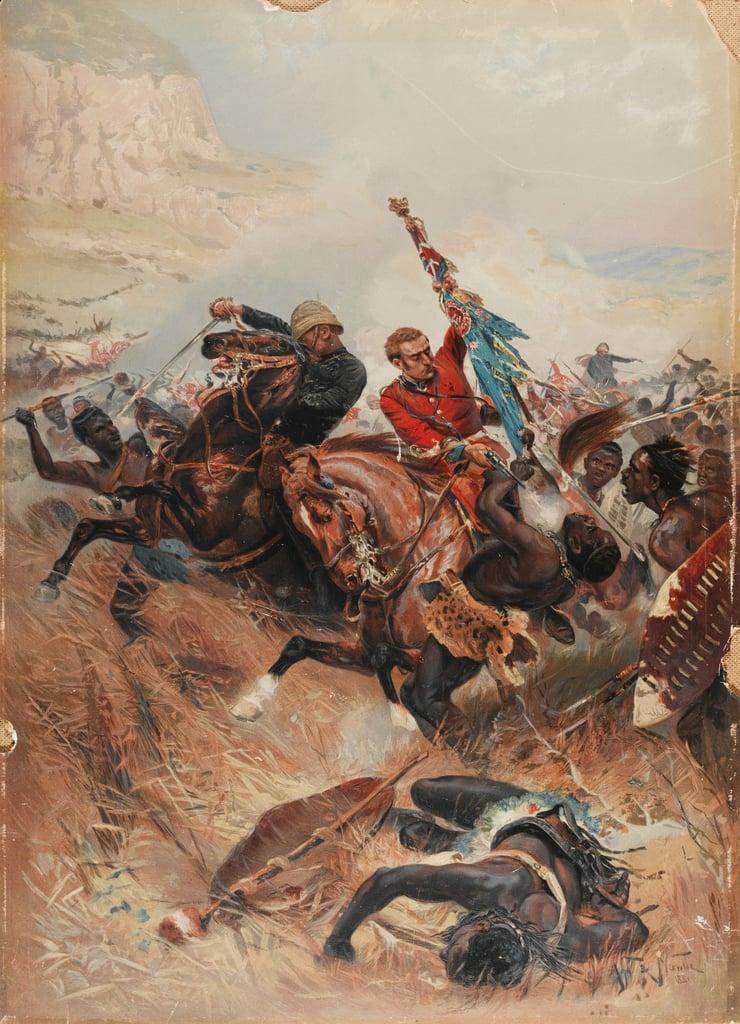

Alphonse De Neuville gives us a clue. In his famous painting of the finding of their bodies, he portrays the two as being wholly intact and un-mutilated, despite having lain decomposing in the heat for almost two weeks. They lie together, while Major Black stands sorrowfully over them and a contingent of 17th Lancers can be seen in the background. Problem was that the Lancers hadn’t even arrived in the country by then.

Lieutenants Melville and Coghill Saving the Colours. Painting by Alphonse De Neuville

But note that the two are lying on the flat, close to the river, not halfway up a dirty great mountain. That is probably the most accurate part of the painting.

The second bright spot is the story of 427 Private Samuel Wassall, 80th (Staffordshire) Regiment attached to the Mounted Infantry who earned a VC for rescuing Private Westwood from drowning while under fire. Wassall’s account is as follows -

The only way to escape was by the Buffalo River, six or seven miles away and we had to get cross it into our own territory, Natal. A main road led to the river but the road was cut off by the Zulus and I had to take a road across the veldt, I knew nothing about. But, I was not in the mood to care which way I went so long as it took me away from the enemy, and so I furiously went on, stumbling over the rough rocky ground, expecting every instant that my horse, a Basuto pony, would fall. In that case I should not have had a chance for the Zulus would have been upon me before I could have got up again. To this day, I cannot understand how a living soul got away from Isandhlwana, because we were seriously harassed by the savages, shots came after us and clouds of spears, but I did escape from the field of the massacre and reached the Zulu bank of the river, and saw on the other side of the Natal territory, where my only hope of safety lay. I knew how dangerous the river was; there was a current running six or seven mile an hour, no ordinary man could swim it. But, the Zulus had a curious ways of using their elbows which made them able to get across. I drove my horse into the torrent, thankful even to be in that part and was urging him to the other side, when I heard a cry for help and I saw a man of my own Regiment, a Private named Westwood, was being carried away. He was struggling, desperately and was drowning. The Zulus were sweeping down to the river bank, which I had just left and there was a terrible temptation to go ahead and just save one’s self, but I turned my horse around. Then I struggled out to Westwood, got hold of him and struggled back to the horse with him. I scrambled up into the saddle, pulled Westwood after me and plunged into the torrent again, and as I did so the Zulus rushed up to the bank and let drive with their firearms and spears, but most mercifully I escaped them all and with a thankful heart urged my gallant horse up the steep bank on the Natal side and then got him to go as hard as he could towards Helpmakaar (sic) about fifteen miles from Isandhlwana.

Samuel Wassall (Wikipedia)

Wassall’s Citation for the Victoria Cross reads as follows –

For his gallant conduct in having, at the imminent risk of his own life, saved that of Private Westwood, of the same Regiment. On the 22nd January 1879, when the camp at Isandhlwana was taken by the enemy, Private Wassall retreated towards the Buffalo River, in which he saw a comrade struggling, and apparently drowning. He rode to the bank, dismounted, leaving his horse on the Zulu side, rescued the man from the stream and again mounted his horse, dragging Private Westwood across the river under a heavy shower of bullets.

It is curious to speculate why Wassall was singled out for an award, when many others must also have been performing identical acts of bravery in an attempt to save their fellows. Cynics tell you that whatever bravery awards issued for that day, either Victoria Crosses or Distinguished Conduct Medals, were carefully doled out to each Regiment or Corps involved in order to satisfy each Regiment’s honour.

If you would like an unforgettable experience join us on the Fugitive's Drift Walk 3-5 September 2021. Click here to for all the details.

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.