Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In its heyday, black African competitive cycling on South Africa’s gold mines received little publicity either locally or internationally. Nevertheless, it flourished for nearly three decades, beginning in the late 1950s and extending into the mid-1980s. Today it has been almost totally forgotten. However, a recently published biography of a leading South African cycling personality of the period, entitled Basil Cohen: South Africa’s Mr. Cycling, vividly recalls this lost history of Black South African cycling.

Drawing extensively on this biography and supplemented by several other related sources, this article traces the rise and then the decline of black cycle sport on South Africa’s gold mines in the latter half of the 20th century. Basil Cohen’s central role in this development warrants an outline of his biography.

Basil Cohen (1939-2014): South African Cycling personality extraordinaire

The 2013 biography by Igor Broes is a tribute to Basil Cohen as an indefatigable cycling enthusiast, ambassador and entrepreneur. Nevertheless, Basil’s name remains largely unknown to all but the cognoscenti of South African competitive cycling. The book itself is a profusely illustrated, privately-produced limited edition volume distributed exclusively amongst Basil’s family and his close cycling friends of the time, making it a rare piece of Africana sporting history.

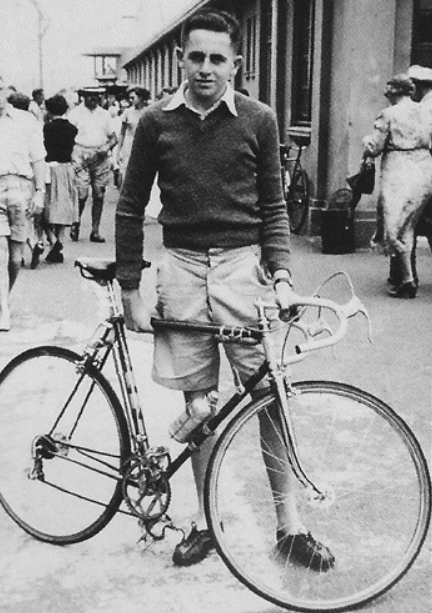

Born in Johannesburg in 1939 into a middle class Jewish family, Basil Cohen did not excel at school either academically or in sport and, in his early teens, he found solace in riding his first racing bicycle. This was an imported blue Phillips ‘Phantom’ built from 531 Reynolds lightweight tubing and purchased from Deale & Huth Cycles in central Johannesburg. (As matters were to turn out subsequently, Deale & Huth Cycles was to become a name synonymous with Basil). He soon became involved with the local Northern Wheelers cycling club and at age 16 found employment with the bicycle wholesaler, L.K. Hurwitz and Son. The company had been awarded the national distribution agency for Raleigh South Africa.

A young Basil on holiday in Durban in the early 1950s with his road machine

By the late 1950s, Basil had succeeded in establishing himself as an accomplished racing cyclist on both road and track. In 1957, he was selected to represent South Africa at the 5th Maccabi Games in Israel in the two stage title road race in which he finished 11th overall. Then, in 1963, by which time Basil was 24, the Deale & Huth bike shop went bankrupt and Basil took the plunge and took over the defunct business. It was to prove a decisive move which ultimately led to him becoming one of the most influential but largely behind-the-scenes figures in the history of the development of competitive cycling in South Africa and in the growth of Black cycle sport in particular. It was these activities, coupled with his business acumen in building up Deale & Huth into a major lightweight cycle dealership, which resulted in him being dubbed ‘South Africa’s Mr. Cycling’. In effect, he became South African cycle sport’s ‘go to guy’ of the apartheid era.

Iconic Deale & Huth cycle shop in central Johannesburg

The development of Black competitive cycling on the gold mines

Deep level gold mining activities expanded rapidly in South Africa after World War II, with nearly 40 mines being located along the gold reef which extended for some 500km. from the Witwatersrand in the Transvaal into the Orange Free State province. Gold mining is a labour intensive activity and hundreds of thousands of Black men were contracted as long term migrant workers from both within South Africa and beyond. They were accommodated on site at their mines in massive same sex hostels. The mining companies thus found themselves with large numbers of Black mine workers who had little to occupy their leisure time.

In the circumstances, the idea of providing on site entertainment in the form of organised athletics and cycling meetings with competitors drawn from the Black SAAA&CF proved highly attractive. Mining companies promptly began to build dedicated state-of-the-art outdoor athletics and cycling stadiums at many of their mines. The first was constructed at the Virginia Mine in the Orange Free State in 1958, and ten more stadiums were completed at mines across the gold mining belt in the 1960s. Their banked cycling tracks, finished in smooth cement, ranged in length from 450 to 500 metres and enveloped 440 metres athletics tracks. In many instances, the mine cycling tracks and spectator facilities surpassed in quality those available to White cyclists elsewhere in the country.

The mining companies, using profits derived mainly from mine hostel beer halls, were keen to fund experienced cycling coaches and purchase the best in racing machines and equipment to develop cycle sport amongst their Black employees. Basil Cohen, with his contacts with coaches and officials in the White cycling community and being the proprietor of a leading lightweight Johannesburg cycle retailer in Deale & Huth, was the ideal person to expedite these matters. He rapidly became a key figure in the Black cycle racing initiative on the gold mines in the 1960s. Coaches, who included top former White cyclists, were engaged to identify potentially talented cyclists from amongst the Black mine workers and those selected were given intensive training.

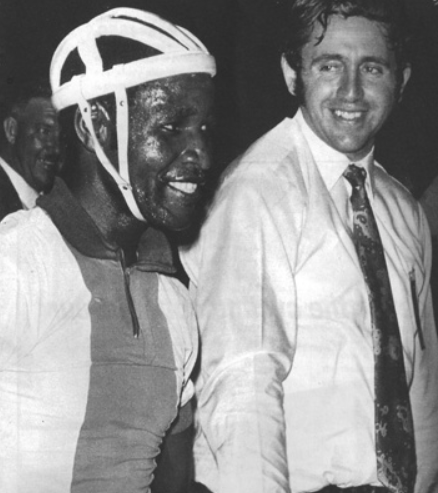

1970s SA Black match sprint champion, Siphiwe Ngwena, of Marievale Consolidated Mines, with his mentor and coach Tommy Shardelow (1952 Helsinki Olympics double silver medallist and multiple SA match sprint title winner in the 1950s).

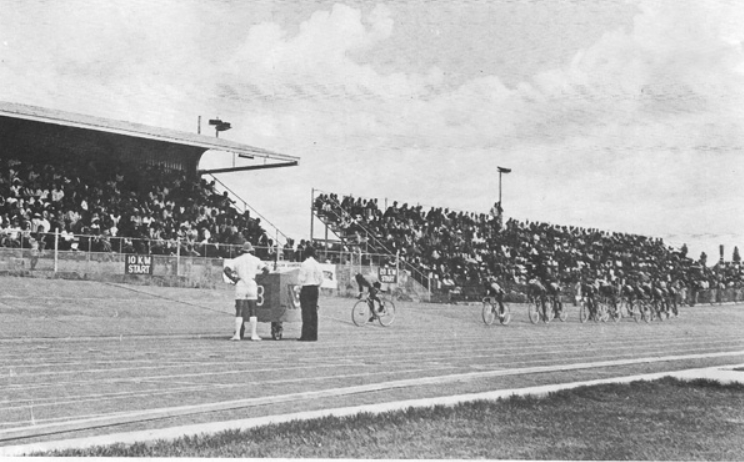

Black cycling officials were also trained, and in due course formal track racing meetings which combined both athletics and cycling were organised on a regular basis under the auspices of the Black SAAA&CF. At its height, the SAAA&CF had some 500 active registered racing cyclists on its books, distributed mainly across the gold mines. Inter-mine rivalries were fostered and track meetings attended by between 5,000 and 10,000 enthusiastic miner-spectators were contested between teams drawn from the various mines. During the 1960s, Black competitive track cycling thus became a major spectator sport on the country’s gold mines, so much so that local White cyclists often raced ‘unofficially’ in these meetings despite risking being officially sanctioned. The major track meetings had as many as 150 riders competing in a wide variety of events including championship races like the team pursuit and the match sprint, plus novelty events such as the ‘Devil take the hindmost’.

1976 Black South African track championships, Libanon gold mine, Westonaria, north-west Transvaal. Note the large number of spectators, estimated to be 10,000.

Pefeni Mtembu of Libanon gold mine being congratulated by Basil Cohen after winning a bronze medal in the 1973 South African Games.

Star Black cyclists who emerged on the mine tracks in this period included Edwin Biko (rated by Cohen as the best Black South African cyclist ever), John Moding, Pefeni Mtembu, Siphiwe Ngwena, Jack Ntseou, Elias Ramantele and ‘Skelm’ Selatwe. Given their talent, they were released from most of their mine duties and became in effect sponsored amateurs. In 1968, a team of six Black mine cyclists from South Africa was selected to contest a ‘test match’ on the track in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) against a Black Rhodesian national team. With Basil Cohen as team manager and a SAAA&CF cycling official, Sipho Matala, as his assistant, the team’s riders were Dennis Khumalo, Stanley Malang (individual pursuit), Pefeni Mtembu, Thammy Phelani, Samuel Ramabodu (10 mile champion), and Jack Tshali (match sprinter). Together they succeeded in defeating the Rhodesian selection in a series of events and returned to a heroes’ welcome on the South African mines.

Samuel Ramabodu, Western Holdings Mine, with South African 1952 Helsinki Olympic silver medallist, Jimmy Swift. Ramabodu also participated in the 1975 Rapport Toer.

Competitive cycling on South Africa’s gold mines continued to flourish in the 1970s. As the decade progressed, Black mine cyclists became increasingly involved in racing at international level:

- In 1973, a team from the Doornfontein Mine, managed by their mentor, Jimmy Rose, raced in Mozambique against Portuguese riders. The team consisted of Abie Oromeng, George Pitso, Sam Ramabadu, Elias Ramantele and ‘Skelm’ Selatwe.

- In 1974, four riders were selected to represent their home country, Botswana, at the British and Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand. They were Stanley Malang, John Moding, Abie Oromeng and Jack Ntseou.

Elias Ramatele being congratulated by Jose Arregui, MD of the Spanish components manufacturer, Zeus, after winning the 1971 Basil Cohen Trophy. Basil (right) was an official at the meeting and is wearing a ‘Referee, Cycles’ armband.

In the 1960s, White South African cycle sport, which was controlled by the South African Cycling Federation (SACF), had found itself increasingly isolated internationally because of practicing apartheid in sport. Excluded from participating in the Olympic Games from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics onwards, in 1970 it was finally suspended by the Union Cycliste International (UCI). White SACF cyclists could therefore no longer compete in the annual UCI world championships or in any UCI affiliated races abroad. In short, White South African competitive cycling faced a crisis. This produced a sudden change of heart at the SACF which is described in the Cohen biography as follows (p.11):

In 1970, Cyril Geoghegan, SACF President, announced that cycling teams would from then on only be selected on merit and that race would no longer play a role. Basil Cohen, representing the SAAA&CF, told a reporter that he was stunned by Geoghegan’s sudden interest in black cycling now that his federation had been kicked out of the world cycling body. He said that few SACF officials had ever attended a black cycling event, but now all of a sudden they wanted to be at the forefront of promoting black cycling.

The SAAA&CF alluded to here was the ‘South African Amateur Athletic and Cycling Federation’, which represented Black athletes and cyclists, including those from the country’s gold mines.

Black cyclists and the South African Rapport Toer stage race

In the early 1970s, the White SACF thus faced the crisis of international isolation for practicing apartheid in sport. In consultation with the apartheid state, the SACF proposed the creation of an international ‘rebel’ two-week, 2,000km. amateur stage race between Cape Town and Johannesburg which would include both foreign and local teams. The big difference would be that the local teams would consist of both Black and White riders. For Black riders, the SACF turned to the SAAA&CF which provisionally agreed to field a team of its cyclists from the mines. Thus, in 1973 when the first ‘Rapport Toer’ was to be held, for the first time in the history of South African cycle sport, Black and White riders were scheduled to compete together with official blessing. Black cycling was finally about to emerge from the shadows of the mine dumps.

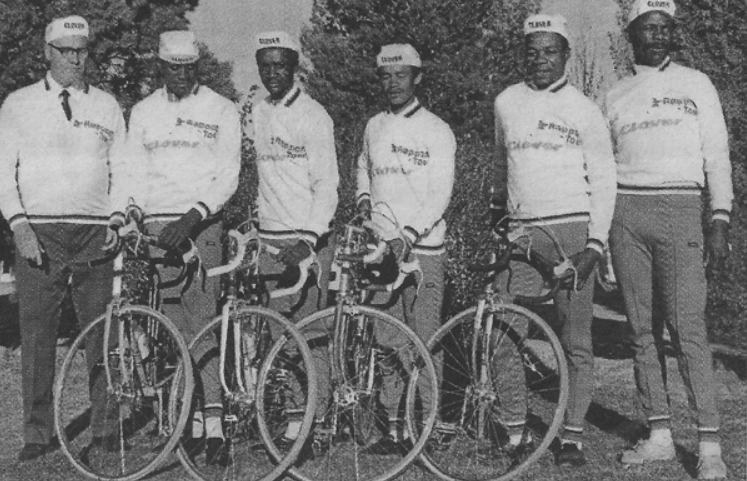

Clover team in the inaugural 1973 Rapport Toer: George O’Brien (manager), Richard Moteka, John Moding, Abie Oromeng, Elias Ramantele & George Shabalala (assistant manager).

The White SACF’s idea behind the Rapport Toer was to demonstrate to the UCI that it was sincere in its attempts to racially integrate cycle sport in South Africa. However, the apartheid government was adamant that Black and White cyclists could only compete in events together in South Africa provided that it was an ‘international contest’ and, to qualify as an international contest, an event had to include a minimum of three foreign teams. This created a new problem for the SACF since the foreign cycling nations were affiliated to the UCI which had banned its members from competing against SACF cyclists. How could this problem be surmounted? To do so, the SACF organisers of the Rapport Toer turned to Basil Cohen for advice and help.

During the 1960s, in the course of building Deale & Huth up into a major lightweight cycle dealer in South Africa, Basil had travelled extensively in Europe, most notably in France and Italy, to establish trade links with major manufacturers of lightweight machines and equipment. In the process, he had developed ties with key players in the European cycling scene of the day, including team sponsors and suppliers. To quote from the Cohen biography (p.12):

The government conceded (to the idea of the Rapport Toer) but only on condition that at least three overseas teams would have to take part. The tour organizers knew that there was only one person who could achieve that, namely Basil. He flew to Europe and with his connections there, Basil got an Italian and two French teams to participate in the first Rapport Toer…

When the field finally lined up in Cape Town in October 1973 for the start of the first Rapport Toer, it included not only the three foreign teams and several White South African teams but also a team of Black mine workers. Each team consisted of four riders together with support staff and each team wore kit emblazoned with the logos of local sponsors. The Black team was sponsored by ‘Clover’, a national dairy, and its riders were John Moding, Richard Moteka, Abie Oromeng and Elias Ramatele, managed by George O’Brien and assisted by George Shabalala.

The 1973 Rapport Toer was won by the Italian, Pierre-Luigi Tagliavini. South African Alan van Heerden won the points title and John Moding of the Black team put in a tremendous climbing performance to eventually share the King of the Mountains title with the White South African rider, Mike Carey. Moding had previously won several of the annual Potchefstroom to Johannesburg (Soweto) races including the last one to be staged in the early 1970s. Overall, the Black riders acquitted themselves well, ensuring the presence of a Black team in all subsequent annual Rapport Toers during the 1970s. The veteran British ex-Tour de France rider, Arthur Metcalfe, who won the second Rapport Toer in 1974, remarked in this regard:

It was a good race … comparatively flat overall but hard fought with a high standard of competition. I had written off my chances after six days, but with three days to go with two stage wins I took over the yellow jersey. Of the South Africans I was particularly impressed by Van Heerden … The Bantu (Black) team, too, were all very strong and with a bit more know-how would be quite a force. (Arthur Metcalfe’s comments as reported in Cycling, 26 October, 1974).

Basil with Arthur Metcalfe, 1974 Rapport Toer winner.

Metcalfe was a member of a shadow ‘England’ team in the 1974 race which included fellow Englishmen Alan Mellor and Pete Edwards. The team rode in the strip of sponsor ‘Quagga-Trek Petrol’ and finished third overall in the team race. Its riders were subsequently suspended by the BCF for participating in the rebel event as were the ‘Mum for Men’-sponsored team of Scots riders of whom John Curran won two stages in the 1974 Toer. Other foreign teams that took part generally escaped sanction by their national cycling bodies and Portuguese squads went on to dominate the race in the 1970s.

In the 12 years from the inception of the Rapport Toer in 1973 through to 1984, a total of some 25 Black cyclists participated in the annual event. The most successful were John Moding who won the King of the Mountains in 1973 and the first Black cyclist to win a stage was Jack Ntseou in 1979. He won the 194 km. stage 7 between the Verwoerd Dam and Bloemfontein by 19 seconds in 4:44:08 (average speed 41kph) after a solo breakaway. Several Black riders participated in a number of Rapport Toers, with Ntseou holding the record of seven successive finishes between 1974 and 1981. He failed to finish only in 1978 and his highest overall finish was 16th in 1977. Abie Oromeng participated in five successive races (1973-1976) and John Moding in three (1973, 1976 and 1980).

Jack Ntseou, aged 35, in the 1976 ‘Tour of the Wineland’ stage race in the Western Cape. In 1975 he finished third in the event. In 1976 he suffered a broken wrist but still finished the race in the middle of the field. Ntseou became the most celebrated Black cyclist in South Africa because of his impressive palmarès: Represented his home country, Botswana, at the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games; participated in eight successive Rapport Toers (1974-1981; first Black cyclist to win a Rapport Toer stage (in 1979, winning in a solo break by 19 seconds); as a veteran, finishing third in his age group in the Veterans World championship in St. Johann, Austria in 1985.

Records are incomplete but the following 21 black riders competed in Rapport Toers between 1973 and 1984 (details for 1978 and 1983 were not found)

The decline of Black cycling in South Africa in the 1980s

In the late 1970s the White SACF succeeded in convincing the cycling section of the Black SAAA&CF to merge with it. This move was largely prompted by the UCI’s insistence that South African cycling needed to have a single, racially integrated governing body before it could be considered eligible for readmission to the world body. The organisation which had run Black cycle sport for decades thus suddenly disappeared without trace. In the process, its structures of dedicated officials, administrators, event organisers, team managers and coaches rapidly disintegrated and the vibrant sport associated with these collapsed. To quote from the Cohen biography (p.13):

Basil says that it is sad that after the SACF opened up sport to all races in the mid-seventies, the black community became demoralized. ‘The black cyclists were left to sink or swim. There was no guidance or coaching; no support structures to replace previous private and individual initiatives. The Federation could have capitalised on all the stadiums and what the mines had done, but it simply didn’t happen’. After having spent a lifetime supporting and promoting black cycling and having seen it flourish in the sixties and seventies … (he) witnessed it decline in the eighties.

Despite all the SACF’s numerous attempts and strategies to win readmission to world cycling, it was not until apartheid was totally abolished in the 1990s that South African cyclists were welcomed back into the international cycling fold.

By then, the halcyon days of Black competitive cycling on the velodromes of the gold mines and on the road in events like the Rapport Toer were over. However, it remains an integral part of South Africa’s history of 20th century cycle sport which deserves to fully acknowledged, remembered and honoured.

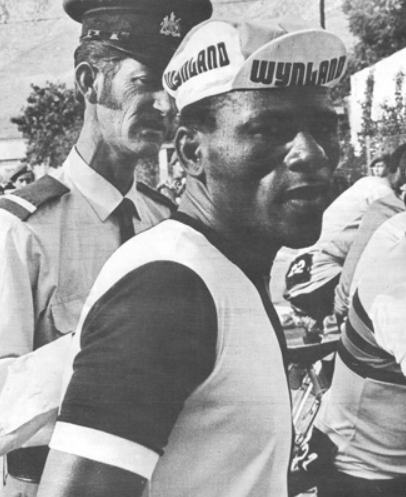

Main image: Start of the 1974 Black South African Road Championships at Hartebeesfontein, Transvaal, with Basil Cohen (standing pointing, centre) officiating. The event was won by Edwin Biko.(Note mine shaft in the background, right).

Archie Barnwell, friend, colleague and protégé of Geoff has taken on the task of ensuring that Geoff’s work on the “untold" history of Cycling in South Africa reaches a wider readership as this sporting history and the impact of racial division and apartheid make this yet another South African story worth telling.

About the author: Geoff Waters passed away in November 2018. He was a Sociology Lecturer at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, and after his retirement wrote a number of South African Cycling related history articles. He was dedicated to recording the untold South Africa Cycling sporting history and researched archives and press cuttings and interviewed a number of cycling figures involved in the promotion and participation of apartheid era cycling sport.

He was a passionate cycling enthusiast, with an intense interest in international and local cycling . He played a key role in many young cyclists' lives, with words of advice and encouragement. He served in a number of administrative roles in Kwa-Zulu Natal cycling, and was instrumental in the organisation of a number of major cycle racing events. Geoff wrote a number of articles which have been published in the “Classic Light Weights” UK cycling magazine and for South African cycling newsletters and online portals. He completed the “100-Year History of Kings Park Cycling Club - Durban” in the past few years and this final work “History of Natal Cycling” is pending publication in the Zulu Natal History journal.

References

- Beneke, Mark, Gary Beneke, Tim Noakes and Mary Reynolds (1989) The Lore of Cycling. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Broes, Igor (2014) Basil Cohen South Africa’s Mr Cycling. Private publication.

- Burns, John (1976) South Africa … Where Now?. Supplement to International Cycle Sport Magazine.

- Cycling. 26 October 1974.

- Jowett, Walter (1982) Centenary: 100 years of organised South African cycle racing. Pietermaritzburg: South African Cycling Federation.

- Learmont, Tom (1990) Cycling in South Africa. Sandton: Media House Publications.

- O’Toole, Sean (2013) ‘Apartheid was the spoke in SA riders’ wheels’. Mail & Guardian, March 3-14 2013, p. 18-19

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.