Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 started a gold rush that surpassed the Californian (1849), Victorian (1851) and Barberton (1885) rushes and the initial boom created the city of Johannesburg, which was literally and figuratively built on gold. The initial boom lasted for three years as the mining companies followed the sloping reef into the earth’s crust and then in 1889 the bust happened, as the gold appeared to suddenly run out which in turn caused a pall of pessimism to hang over the diggings. Read on and you will discover what happened next.

Boom times outside Johannesburg's First Stock Exchange (The Johannesburg Saga)

In early 1886 an itinerant gold prospector and stone mason, by the name of George Harrison, was passing through an area of the Old Transvaal, between the Vaal River and Pretoria known as the Witwatersrand (Ridge of White Waters), then a windswept wilderness without a tree to be seen. He was on his way to the Barberton goldfields when he stopped on route to ask for casual work from the Struben brothers who were prospecting for gold (in what is now Strubens’ Valley). They could not oblige him but instead sent him over to see Widow Oosthuizen, who needed walls built for a house, on a section of the farm Langlaagte (south of the ridge). Whilst in her employ he was walking over the veldt, on a Sunday in February 1886, and happened to stumble across an outcrop of “banket” rock and as the story goes by chance found the exposed upper portion of the Main Reef (which ran east to west) that would lead to the richest goldfield in history. He would stake a claim but he soon realised that the nature of the conglomerate rock needed expensive mining methods to release the gold, which was beyond his means and thus he sold his claim for £10 and moved off stage into obscurity. It would take “Big Business” to unlock the wealth of the goldfields and it was left to the diamond barons of Kimberley, the men who had the wherewithal to finance the diggings, with J. B. Robinson (the Buccaneer) leading the charge.

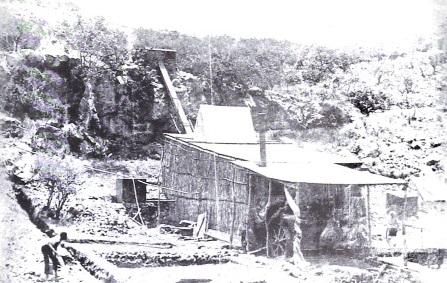

One of the earliest photos of mining on the Main Reef (via South African Mining)

Trenches in the Veld (via Gold Gold Gold)

One of the first gold crushing mills on the Witwatersrand (via Gold Gold Gold)

Within a year many thousands of adventurers would flock to the Witwatersrand and they would become known by the Boers (farmers) as the “Uitlanders” (foreigners) and this influx of people would, in next to no time, build a boomtown beside the diggings to be called Johannesburg. No one knew at the time the extent of the goldfields or when the gold would run out and the drive was to “get rich quick” before it did.

Police quelling Uitlander unrest in early Johannesburg (via Gold Gold Gold)

Johannesburg was seen by the Transvaal’s burgers as a den of iniquity; if you like Sodom and Gomorrah in their midst and they very much hoped that the gold would soon peter out, as it had elsewhere and that they would be left, once again, in peace to carry on their pastoral way of life. Their prayers were answered when after three years of profitable gold mining the grades of gold (ounces per ton milled) suddenly began to decrease alarmingly. This caused the stock market to crash and mines to close and very few people believed that Johannesburg would ever recover; it was the Barberton experience all over again. Panic and pessimism overwhelmed the town and in 1890 one in three of the populace left; for months Market Square was piled high with furniture for sale.

We know of course it was not the end for Johannesburg and it did not become a ghost town with grass growing in its streets (as predicted by Percy Fitzpatrick), but suppose Johannesburg had faltered then our history would have been very different; there would have been no Jameson Raid (1896), no Boer War (1899 to 1902) and certainly (for good or bad) no modern industrialised South Africa as we know it today. We certainly would have taken a different path.

It was not the end for Johannesburg. Skyline in 2016 (The Heritage Portal)

If panic and pessimism was the effect what was the cause? The causation was in fact a change in the nature of the reef in which the gold (Au) particles were locked, which at first was not fully understood. The upper part of the reef (outcrop zone), which went down to depths of between 100 and 300 feet below the surface, had an ore body that was oxidised (free-milling) and after it was crushed to a powder the tried and tested Amalgamation process of gold recovery, whereby mercury was used, worked well and recovered 70% of the gold (30% going to the tailings waste dumps); this was considered to be acceptable as the process was both cheap and simple to operate (even if it was none too healthy).

All along the Main Reef, for 15 miles, one by one the mines experienced a drastic drop in grade (ounces of gold per ton milled) at a stage when the outcrop zone had been dug out and they were moving deeper into the ore body and uncovering reef that had changed colour from red to blue. When processing the blue reef by Amalgamation the grades were a lot lower than before making mining unprofitable to continue. Some believed that the gold was running out whilst others contended that 30% of the gold was being recovered and 70% was going to the waste dumps, those mountains of sand beside the diggings. What was this blue reef and what was to be done?

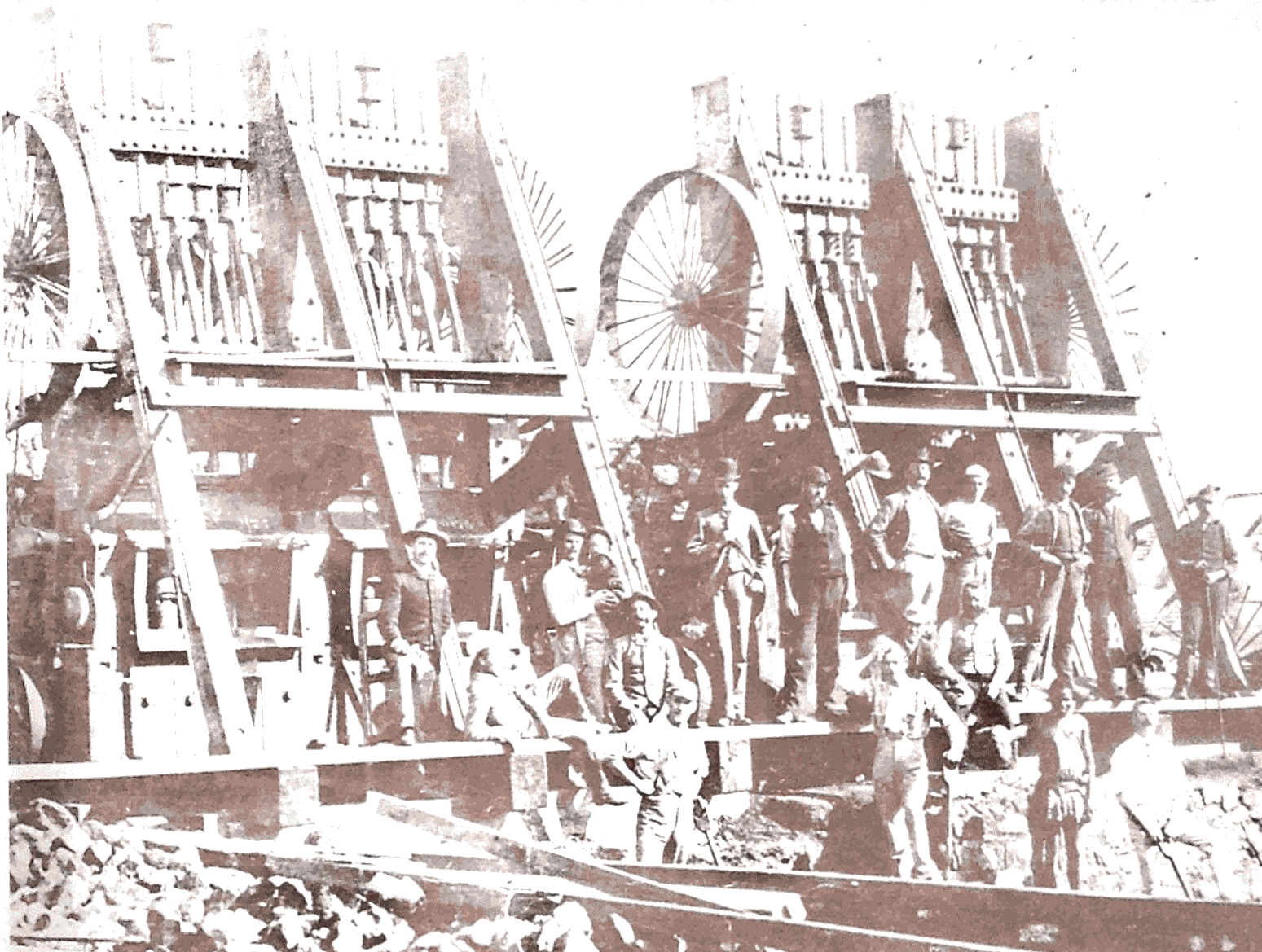

An early stamp battery

The blue reef was unoxidised ore containing Pyrites, not Pirates (although something was stealing the gold) and they had an adverse effect on gold recovery. Ironically the solution to the problem already existed as three men from Glasgow, Scotland had been granted, on the 10th August 1888, a patent – British Patent 14174 “Improvements in obtaining gold and silver from ores and other compounds”, which became universally known as the MacArthur-Forrest process, so named after its inventors, John Stewart MacArthur (a chemist) and the brothers Robert and William Forrest (both medical doctors). The said process involved dissolving crushed gold bearing ore in a weak cyanide solution and then precipitating the gold with zinc shavings.

The MacArthur-Forrest process saved the day for the mines, for when a pilot plant was set up on the Salisbury Mine, to see if the laboratory results could be replicated when scaled up on a mine, the results of tests (between June and August 1890) were a resounding success with recovery being 90% whether from reef, concentrates or even tailings.

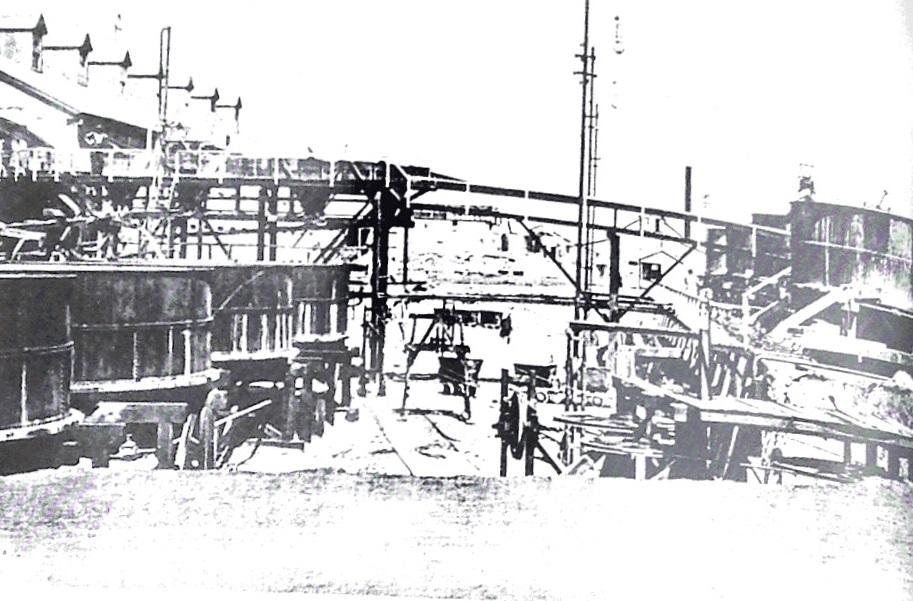

City and Suburban Cyanide Works

The Process soon became the industry standard and got the mines back up and running again by 1892 which gave the mining companies the confidence to take up the challenge of deep-level mining by sinking vertical shafts to the south of the original outcrop, this would guarantee that the mines would be long lasting and that Johannesburg would be the financial hub of South Africa, even before Union in 1910. As Barny Barnato once said in 1889 “I look forward to Johannesburg becoming the financial Gibraltar of South Africa”. How right he was.

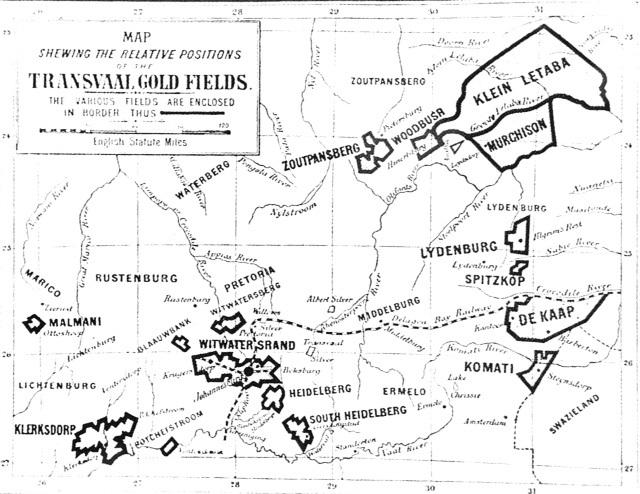

Map of the Transvaal Gold Fields

References and further reading:

- “Diamonds, Gold and War – the Making of South Africa” by Martin Meredith, 2007.

- "Digging Deep: A History of Mining in South Africa" by Jade Davenport, 2014.

- “Gold! Gold! Gold! – the Johannesburg Gold Rush” by Eric Rosenthal, 1970.

- “Like it was - the Star 100 years of Johannesburg” Edited by James Clark 1986.

- “The Discovery of Wealth” by Diko Van Zyl, 1986, Heritage Series: 19th century.

- “The Power of Gold – the History of an Obsession” by Peter L. Bernstein, 2000.

- “The challenge of deep-level mining in South Africa” by H. Wagner, SAIMM 1986.

- “How the MacArthur- Forrest cyanidation process ensured South Africa’s golden future” by C.E. Fivaz, SAIMM 1988.

- “The life, death and revival of the Central Rand Goldfield” by Morris Viljoen, SAIMM 2009.

- "The power of mining: the fall of gold and the rise of Johannesburg" by Philip Harrison (Wits) and Tanya Zack (Wits), Journal of Contemporary African Studies, October 2012.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.