Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

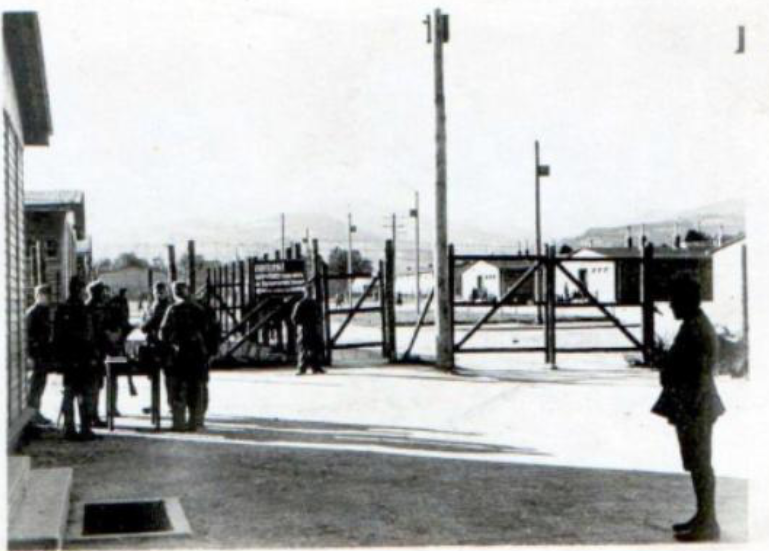

Below is Part 3 of Mel Baker's extraordinary account of being a Prisoner of War during World War II. Click here to read Part 2 and here to download the full account including detailed footnotes. The photo above shows the main gate of Stalag XVIII A (Prisoner of War Camp in Southern Austria).

Leaving Wernersdorf

Two weeks before Christmas 1944 we were informed that we were leaving Wernersdorf the next day. No indication as to where we were going. We were not at all happy about the fact of leaving and also the timing, as we had sorted out all our meals and drinks for Christmas. Lex had made beautiful menus for each of us with items like plum pudding a la (name of a farm). He had drawn army and naval crests at the top of the menu (although the naval one had a crown instead of ships). We even had a bottle of schnapps - that we drank the day of leaving.

The evening before leaving, I visited my girlfriend Paula for the last time to say goodbye.

On the day we were leaving I went to the Windischbauer and got him to let us use the horses and the wagon to take our kit to Wies. While making this arrangement, he gave me a farewell sample of schnapps.

We left with very mixed feelings. After three years in Wernersdorf, we had got ourselves very well organised and were probably in the best situation that a prisoner of war could be. No other camp could compare with what we had. We could only be moving into a worse situation.

We finally left Wernersdorf and had a longer than usual walk to Wies. We boarded a train to Graz, which had been badly bombed. The train couldn’t go to the station and stopped a few miles outside. We had to walk carrying all our belongings to the other side of the city to catch another train, which headed to Trofaiach. The civilians who had suffered the intensive bombing were very hostile. The guard told them that we were not Americans but English POWs, which eased the situation somewhat.

Our journey to Trofaiach took two days, stopping at a railway junction called Knittelfeld (a city in Styria), which had been bombed every night for months. We were in a tin hut in the middle of the rail junction and prayed that we would not be bombed by the allies. Luck was with us as it was heavily overcast and no bombs were dropped that night. We heard planes flying over to bomb Wiener Neustadt (a big industrial area). I was lying on my back with my cap over my eyes talking to the guard. Another guard arrived and wanted to know from the first guard who he was talking to, and to his surprise was informed that I was one of the POWs.

The next day we arrived in Trofaiach. We were billeted in a double-storey house. The upper floor was already occupied by about 15 POWs who had been there for some time. We were there to quarry iron ore. The task for the day was to fill a certain number of skips. When the quota was filled the guys went back to camp. When we got there it was freezing and exceedingly hard work. The chaps who were already there had it taped, but we battled. All the rocks which were too big to be tipped through a grid into the stockpile had to be broken with a sledgehammer. One of the English prisoners was working the rubble loose from under the top layer, which was frozen hard. It suddenly collapsed and his legs were caught under tons of rock. We dug him out and he was taken to hospital in a town about ten miles away. Both his legs were amputated, but he didn’t survive – he died that same night.

I hated the job and eventually developed a “bad foot” and “hobbled”. Actually, all I had was a blister on the back of my heel and the boots rubbed on it. It became very uncomfortable to walk. When I put my shoes on I could walk fine, but I still hobbled. The shoes were the ones I received in one of my parcels from home. They were not very good for walking in the snow. I finally persuaded the guards that I couldn’t work and was sent to Stalag XVIII A. By the time we left Wernersdorf, Red Cross parcels were not coming through on a regular basis and the poor rations in camp were not very good without Red Cross parcel supplements. In Trofaiach we got the usual coffee breakfast; midday was stew which at the start had plenty of potatoes and was quite nourishing, but after a while the potatoes ran out and were substituted with cattle-feed turnips. So life deteriorated pretty badly, and talk about wonderful meals started all over again.

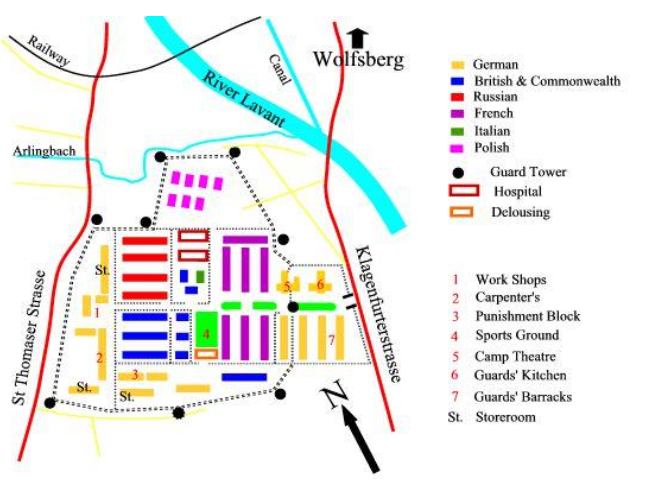

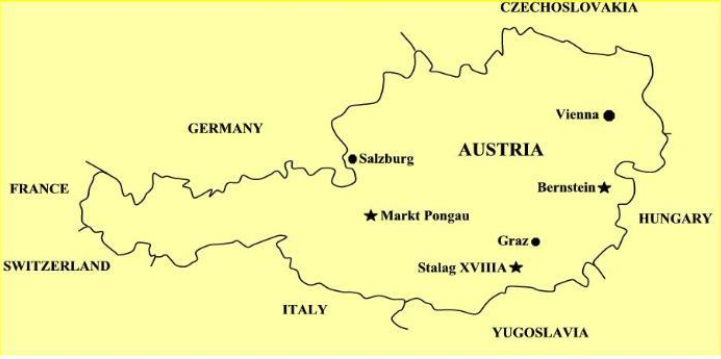

From Trofaiach I was taken by train to Stalag XVIII A at Klagenfurt, which had about 10,000 men. Life in the big camps was the worst apart from the camps before Wernersdorf. At least this camp was well-run and organised. Food and parcels were scarce. By now Germany’s transport was in shambles. The Allied bombing had damaged railways and the fighters had pepper-potted engines. We saw one engine towing five others to the workshop for repairs. The only way we got food parcels now was by truck from Switzerland. The Red Cross organised trucks in Switzerland to carry the parcels to us. POWs were allowed to go into Switzerland to fetch the parcels to bring into the camps. It was a case of one parcel among at least five or six about twice a month. One can imagine what would have happened to any of the POWs had decided to stay in Switzerland. Reprisal after the war would have been vicious.

Plan of Stalag XVIII A

Position of Stalag XVIII A in relation to Graz

The ingenuity of POWs in these camps was incredible. The parts to make a wireless were smuggled into the camp and tuned into the BBC news. Someone would go around to all the huts and read the latest news. A close watch was kept to ensure no guards were near. I acquired, for the price of a few cigarettes, a little stove made from the Red Cross parcel tins. It was in the form of a blower. A Klim tin had a fan in it which was turned by a handle outside the tin, which made the blower to another smaller tin in which a few sticks of wood were sufficient to heat enough water to make tea. It worked on the same principle as a blacksmith’s forge.

By now there were no communal activities at Klagenfurt in the camp. Life was boring – the same routine every day. How some of the POWs preferred being in camp to being out in a working party, I don’t know. No wonder a lot of them had changed a lot by the time they got home. To break the monotony the camp commandant would enjoy getting the whole camp on to the parade ground and keep us standing there for hours. We did have a football and could kick it around. The ground was covered in places with cinders and one’s feet were black at the end of the day. The guards enjoyed throwing bits of bread and rotting cheese from their quarters to the prisoners and watching as people scrambled for these scraps. There is very little to write about the monotonous life in the camp.

Our rations were the usual coffee, stew and one loaf of bread to be divided among five men. Quite a job to cut it up equally, but I managed and had to do it regularly as the one who cut the bread had to take the last piece.

I was in a working party sent to a railway siding to load a truck. When a lone plane came over we thought it was a German fighter, but the next thing we saw a rocket leave the plane. It was aimed at us but hit a tree about 50 yards from us. Of course, the pilot couldn’t know we were POWs. This is where I suffered my one and only injury. As we dived under the truck, hopefully for protection, the guy in front of me banged his knee on the rail line, which brought his heel up and caught me in the jaw. Serious wound – cut lip. When the air raid siren sounded the guard had refused to let us take shelter under the trees nearby, but after this – guess who was the first to take cover?

Another working party I was on was to dig a trench across a road. The temperature was well below freezing and the road was frozen solid to about six inches. It was impossible to get a pick into it – it was as hard as concrete. It took me quite a long time to dig a hole deep enough to get the point of the pick into it so that it would hold. I jerked the handle as quickly as I could and managed to break it. One pick down. I did the same with the other two picks, and so we had to be taken back to camp.

About a month before VE Day 80 names appeared on the notice board, mine included, to be transferred to another camp. This was because they were moving us away from the approaching Russians. Some of the chaps in the know laughed at me saying, “Do you know where you’re going? It’s a camp near Hitler’s redoubt and you’ll be the last to get out.” Well, as it happened I had the last laugh. Three weeks later, plus or minus 10, 000 POWs arrived at this new camp. The whole of Stalag 18 A had marched all the way (except for two lorry loads of 80). I had been taken by lorry.

The new camp at Bischofshofen in Austria was very close to the Bavarian border. Life here was the same as Klagenfurt. Rations terrible, but we knew the Yanks were getting closer and the attitude of the guards was changing as they knew the war was virtually over. Some still remained bastards. Our greatest pleasure was to see the bombers going over in their hundreds and fighters shooting up trains, etc.

Two days before VE Day (Tuesday 8 May 1945) the guards knew the war was over and some of them disappeared leaving the gates wide open. An Aussie named Peb and I decided we were not going to wait for the Yanks and started walking down the road to meet them. We first went to a farm overlooking the camp to spend a night in the barn. It was much more comfortable than sleeping on bare boards. There were no beds in the camp. The floors of the huts were about two feet from the ground and the cold night air was worse coming up from the ground as the wind blew under the huts. We also went to scrounge food, but the farmer was not kind to us and wouldn’t give us any. Next morning he was ploughing on a very steep field so we decided to help him and then got some food. Peb traded his overcoat for a bottle of schnapps which he was quite sure would get us a lift. He had it in his side pack and it dropped out several times. I said, “Before long you’ll break it, so we might as well drink it.” Some of which we did. Along the way we came across some cars, which we attempted to ‘borrow’ but none of them would start so we kept on walking. A truck came along full of German soldiers, so we cadged a lift from them. A lot of SS officers were all pulling the SS insignia from their uniforms thinking that the Americans would shoot them all. But that never happened. This lift did not take us very far, so we were back to walking.

Some time later we saw a strange vehicle approaching us. It was jeep. Of course, we had never seen one before. There was an American officer with two soldiers. We got them to stop and informed them about the camp some miles away. They told us there was an army camp at a bridge a few miles away and we should head for it. The road bridge across the river had been completely destroyed and the railway bridge had been damaged. The jeep had managed to get across the railway bridge by riding the boards next to the rails. A big truck tried to follow them but the boards collapsed and the truck was sitting on its axles on the rails blocking the bridge completely, except for pedestrians.

We walked across the bridge to the camp. First thing we looked for food as we had not eaten much all day. It was now late afternoon and the canteen was closed. All we got was somebody’s emergency rations – not much of a meal for two hungry people. The Yanks, who were short of nothing, when hearing our story decided we needed a drink. We had already knocked back a lot of the schnapps. We were given about half a bottle of Benedictine. Their comment on being told how long we had been POWs was, “That’s longer than we’ve been in this goddam war.” We sat for a long time round a fire. It was still cold at night, even in May. After the Benedictine I was given a bottle of cherry brandy. One truck had a wooden box full of booze – at least two dozen bottles. How much of this bottle I drank I have no idea. I finally climbed into the back of a truck to sleep. It was cold and I kept on waking up from the cold.

In the morning I was woken up by a voice saying, “Get the hell out of there. We’ve got this goddam bridge to fix.” I politely told him where I thought he should go, and he realised who I was and sort of apologised. When my eyes opened properly I saw someone’s greatcoat lying next to me. The next thing was to look for food – had a glorious hangover. I was too late for their breakfast, but I saw some bods drinking tea at a mobile kitchen so joined them and was given a mug of tea. It was so sweet that I couldn’t hold it down. All I wanted was unsweetened black tea or coffee. The only food I managed to get was some left-over French toast – not quite what I needed.

Time now to get on the move again. We found a convoy of trucks going to Ulm via Munich. I sat between the driver and his mate. It was driven by a big black guy, full of the joys of life. He gave me a tin of butter and said it would buy me anything I wanted. They wanted me to go to Ulm with them because I could speak German. But no ways – Munich was a far as I intended to go. In Munich there was a facility for POWs the Americans had rescued along the way. They had come through Dachau and saw the results of the concentration camp and were very bitter. One said to me, “Here’s my rifle. If any of those 10, 000 Krauts we have taken prisoner have done anything to you, shoot them, as unfortunately we can’t do it.” There was no way I could ever have shot any of them even if the guard we had in Wernersdorf was one of them.

After two days in Munich we were told that we would be flown to Brussels. Dakotas were to pick us up. We were taken to the air field and put in groups of 14. About 30 groups were transported to the airfield to await the Dakotas. The first day only six arrived. We spent all the time, day and night at the airfield sleeping in the open. There were no facilities, but there was a mobile kitchen so we were at least fed some reasonable food. The second and third days very few Dakotas arrived. On the fourth day I went to each group ahead of me and found one near the front of the queue that had only 13 men. So I joined them and was flown to Brussels that day.

On the way home at last! The camp in Brussels was run by the Canadians. What a well-organised place. We were first stripped of our old uniforms. We went through a lovely hot shower with soap and towels. After showering we were issued with brand-new army uniforms and dusted with DDT powder to ensure we had no vermin. We were given a map of the camp showing where the dry and wet canteens were, sleeping quarters, dining mess and also 5 pounds worth of Belgian francs. We were told to go on the town and enjoy ourselves after we had settled in. On our way out of camp, we were called back and told we were to be taken to Lille in France to be flown to England as the Brussels airfield was out of commission. I had a terrible night on the train. When I got on all the compartments were crowded and had to stand in the corridor. All doors at the end of the corridors locked on the outside when closed as the train had been used to carry prisoners. As there were a lot of weak bladders among the prisoners the doors were kept open. On arrival in Lille we were taken to an airfield and flown to England in the belly of a Lancaster bomber. I spent most of the time talking to the rear gunner and wasn’t affected by the turbulence, which made some of the POWs airsick. We were issued with life jackets. I said I could swim not fly, so where was my parachute?

We landed in England at an airstrip near Horsham and were taken to Brighton by train. What a wonderful feeling after all those years of mixed experiences. We were billeted in houses in Brighton and Hove. We were given a pay book with half the pay due to us and told to take 30 days leave. We were asked where we wanted to go, and if we had no definite destination we were given a rail pass to Inverness. We were asked how we wanted to go home - by air or sea. I opted for air as I wanted to get home as soon as possible. When I got back after 30 days I was informed that no more flying would take place due to some crashes in Central Africa. I now had to wait for a ship and was at the bottom of the roster. I was told to take another 14 days’ leave, and so it went on, until after nearly three months in England I went on board the MV (motor vessel) Rhuys, a Dutch passenger cum cargo ship. The passenger accommodation was for officers and the nurses, etc. Other ranks were in the holds converted to mess decks. The food on the ship was like the ration food in England. We had kippers every day. After 14 days on board, we went on the deck early in the morning to see the most wonderful sight – Table Mountain! At long last, after five years and four months.

A more recent photo of Table Mountain with The Castle in the foreground (The Heritage Portal)

We went ashore and spent the day with a friend from PE (Joey Lappin) whose relations in Cape Town gave us a sumptuous lunch. We entrained for PE that night. It took two nights and a day to get to PE, to be met by my family in the early morning. When we got on the train we thought we would get a really decent meal with a good helping of meat. The trains in those days cooked the food on the train, and it was excellent. When we went to the dining saloon, we did not know that on Wednesday it was meatless day so – we were served kippers.

Click here to find out what happened to all the characters from this story after the war.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.