Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

On a recent journey through the Karoo, the author obtained more than 1500 unusual photographic glass plates – just imagine the total weight of all these photographs.

This find is exceptional in every way, in that many years ago people destroyed these glass plates due to lack of appreciation in the historical value or simply due to them being damaged due to incorrect storage. To discover more than 1500 of these plates therefore creates huge excitement amongst researchers, especially because they seem to originate from a single photographic studio operating in South Africa between 1901 and 1910.

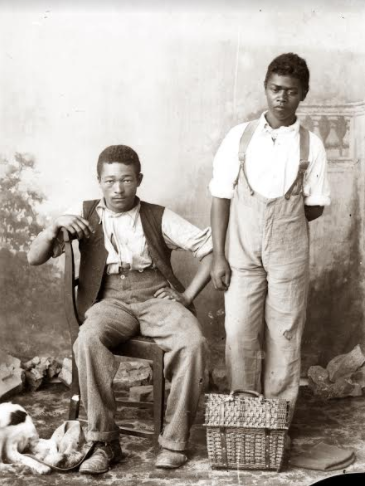

Local Karoo lads

Photographic studio activity of the Victorian and Edwardian eras makes for an interesting social and cultural study. Such studies are mainly enabled by obtaining original photographic material such as the original Carte-de-Visite or Cabinet format photographs or better still, the original glass plate (glass negative) from which these paper-based images were produced.

Glass plates were used in photography from 1850 onwards. Glass, because of its transparency, was used as a support for light-sensitive materials producing either a photographic positive image, such as in the Ambrotype, or photographic negatives such as Albumen, Collodion and Gelatin processes. These glass plates were coated with light-sensitive Silver Salts.

Glass plates were commercially available in standard sizes. During the twentieth century these glass plates were known as dry plates carrying gelatin emulsions. Dry plates, which were more light-sensitive, replaced the wet Collodion process negating messy last-minute chemical preparations. Some photographers bought the plates, already sensitized, in the size for which their camera was designed while the more adventurous photographers preferred to coat their own glass plates.

Glass has also been used for transparencies like the Lantern slide.

Research to date indicates that the studio was more than likely The Central Studio. With the assistance of Dr. Ansie Malherbe (who researched the Graaff-Reinet based photographer William Roe), the conclusion was reached that this studio was based in Aberdeen in the Eastern Cape and that the photographer was more than likely John F Scholtz. A further deduction was that William Roe may also occasionally have been using this studio. The only other studio with a similar name was that of Sheppard’s in Pretoria.

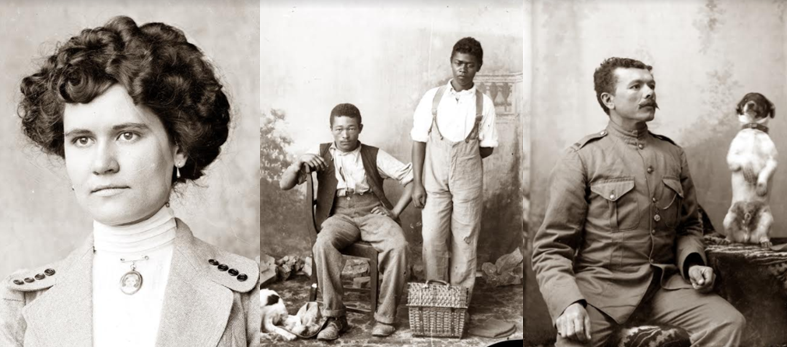

What makes these glass plates unique is that they provide an insight as to how the photographer went about creating his images. This collection contains images of men in uniform, black people, toys, animals, unusual poses and props used in the studio or post mortem images.

Child with unusual tricycle. An item that today would be highly prized by any toy collector.

Child on rocking horse. Onset of deterioration of glass plate can clearly be seen on this image.

The final paper-based images produced from these original glass plates did not include the entire image as it appeared on the original glass plate. Images on the original glass plate negative therefore provide a better perspective as to what the studio set up and background draping looked like.

Often, some unwanted parts of the image (as it appeared on the glass negative) were removed by scratching out or covering whatever was not required on the final paper version. Such deletions can be seen on the original glass plates. For this the photographer or artist used what is known as a touch-up-desk, the old-fashioned Photoshop.

For example, a parent might be standing in the background either holding a child with one hand or simply being there as support. However, in the final paper version of the picture the parent would be edited out.

Note the father in the background - Only the boy would have appeared on the final paper format version

Images of black South Africans, found in various museums locally and abroad, were mainly taken by foreign photographers – with a strong underlying anthropological theme. To find photographs of black South Africans taken in studios is therefore unusual. In some images the servant may sit with the employer’s children but images of an individual black child or black couple still makes for an unusual find - for the simple reason that the luxury of having a photo taken was often out of reach for most people then, not to mention black people. Photography in the earlier years could also be described as mainly a Eurocentric activity or interest.

A child – dressed in Sunday best. The selection of bricks that form part of the studio lay-out is intriguing.

As morbid as it might sound, some photographers in the 19th and early 20th centuries also gave special attention to the photographing of loved ones who have passed away. This was often done when there existed no living image of the deceased. This type of photography is referred to as either memorial, post-mortem or bereavement photography.

In many of these images, the deceased was shown peacefully sleeping. Most of these images can be described as serene or even as thought provoking in appreciating the gift of life (click here to see the author’s article on this topic).

Poses in photographic studios in the mid to late 19th century were prescriptive. In many instances, the sitter (person on photograph) found the process of being photographed as stressful. This resulted in the pictures being formal; non-imaginative with little if any additional props.

During the early 1900s some photographers started deviating from the potential dull and stoic approach resulting in more creative poses. To find a woman, for example, sitting with both her hands behind her head would have been viewed as unfeminine then,

An unusual pose for a female of that era. The pose was probably requested to show off the sleeves of the dress

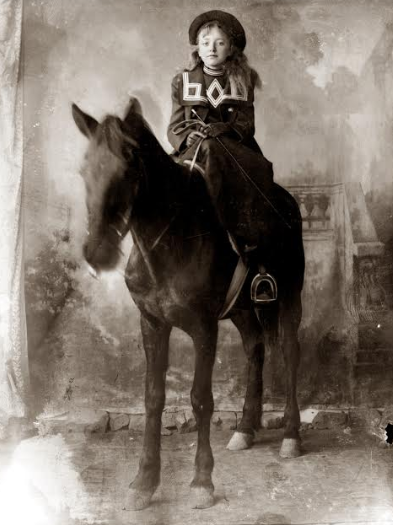

The photographer of this particular studio even allowed a horse into the studio to be photographed with its owner! In another instance the photographer probably had to be patient to photograph the sitter’s dog on his hind legs – remember, exposure times then were much longer than today. Often children and animals came across as blurred on these images due to long exposure times.

Girl on horse in a makeshift studio. Note the background sheet.

Obedient dog - A rather creative photo in that the photographer would have had to “snap” at the right time

Photographs also allow for the study of clothing, jewellery, hats and many other aspects of social and cultural interest.

A beautiful turn of the 19th century lady. Note her brooch containing a photograph of a child

Some people on these glass plate negatives look haggard whereas others seem to be very elegant and proud. Each image tells a story – a story that needs to be unraveled. Sadly, not a single person on any of these images has been identified to date – for that the photographer would have held a separate register.

The majority of these images would have resulted in a final cabinet card format photograph being produced. Often these cabinet cards would have had the detail of the photographer embossed or printed at the bottom or the back of the card. This means that some of these images may still be found in family collections – some with the names of the sitter included.

Now just to match a number of the glass plate negatives with the final cabinet card versions.

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.