Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

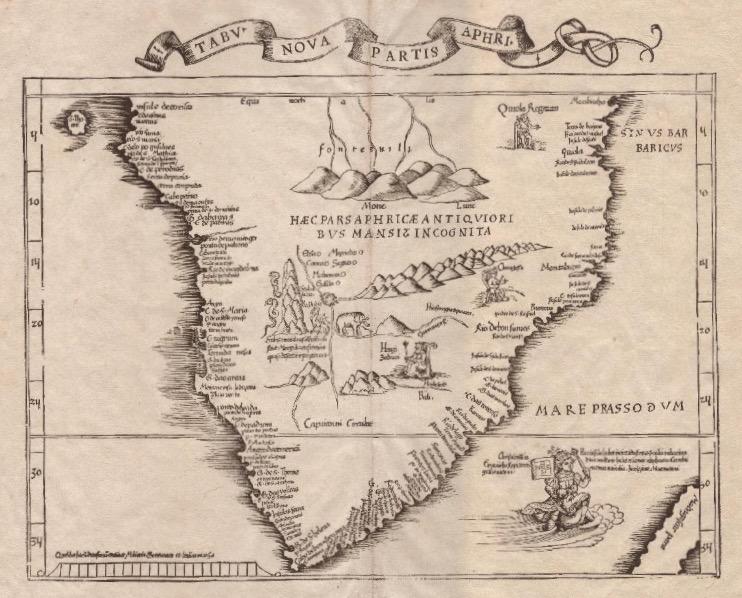

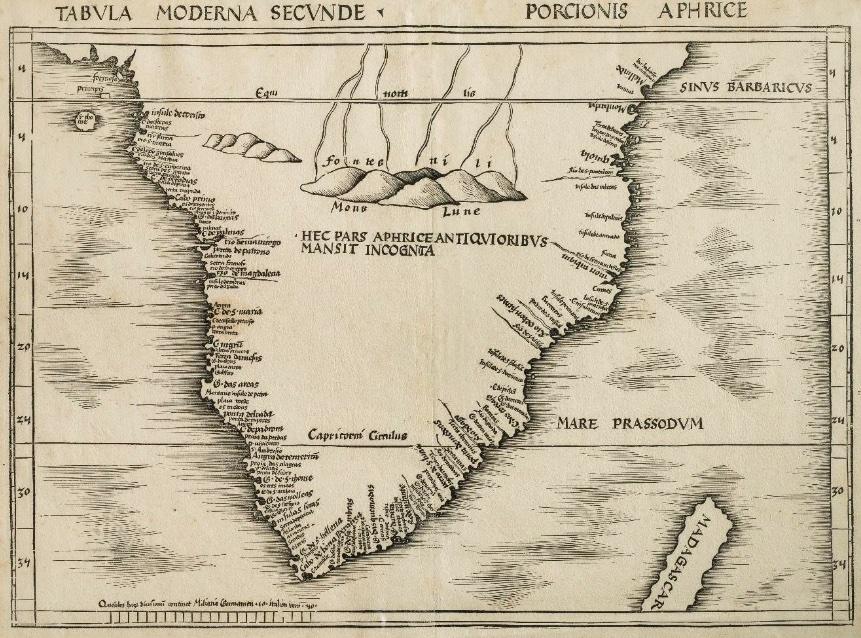

Tabvla Moderna Secvnde Porcionis Aphrice [A modern map of the second part of Africa] is the first printed map of Southern Africa. It was produced by Martin Waldseemüller, a German priest and the most influential cartographer of the early sixteenth century. This map was included in the 1513 and 1520 editions of Ptolemy’s Geographia, published by Johann Schott in Strasbourg, France.

The map (50.5cm x 36.0cm) was printed from a woodblock. The place names on the map include numerous landfalls and coastal sightings recorded by Portuguese maritime explorers. The interior is mostly vacant, and the reason is explained on the map in Latin: ‘Hec pars aphrice antiquoribus mansit incognita’ [This part of Africa remains unknown to the ancients]. The empty spaces have not been filled with decorative elements or mythology – this practice became popular in the seventeenth century.

The map does show the ‘Mons Lune’, the Mountains of the Moon, just south of the equator. According to Ptolemy, these mountains (possibly the range now known as the Rwenzori Mountains) were the supposed source of the Nile, (‘paludes nili’, on the map). The details of the geography of Waldseemüller’s map come from the 1502-1506 manuscript map of the world by Nicolo de Caverio, now at the French National Library in Paris.

Examples of the Waldseemüller map are uncommonly on the market.

The Laurenz Fries map

Laurenz (Laurent) Fries was a French physician and mathematician born ca.1485 in Mulhouse, France, He settled in Strasbourg, where he became interested in the Geographia. There is no evidence that Fries was a woodcutter; nevertheless, he had new woodblocks cut that were reduced (42.5 X 30.5 cm), edited versions of the Waldseemüller maps published earlier by Schott. He first contributed maps to the 1522 edition of the Geographia, published by Johannes Grüninger in Strasbourg. These maps were re-issued, unchanged in the 1525, 1535 and 1541 editions of the book – see below for the distinguishing features of the map of southern Africa in these various editions.

In 1525, Fries returned to writing medical texts. The Grüninger woodblocks changed hands and were last owned by the brothers Melchior and Gaspar Trechsel, who jointly published an edition of the Geographia in 1535 in Lyons, France (see below); Gaspar published the final edition of the map 1541 in Vienna.

Laurenz Fries Map

Oscar Norwich, the South African collector, wrote of the Fries map: ‘The map now has three kings on their thrones, an elephant and two serpents next to a sugar-loaf mountain, while the King of Portugal rides a bridled sea monster on the Mare Prassodum (Indian Ocean), holding the banner of Portugal in his right hand and the scepter in his left. Mountains have been added and rivers appear south of the Mountains of the Moon.’

The map also depicted three indigenous rulers. A crowned, bearded ruler is depicted in ‘Quiola’, presumably Quiloa in present day Tanzania. Charagassa is depicted as a bare-chested ruler near Moncabiqui, i.e., Mozambique. Above the Tropic of Capricorn is the king, Hengi Zedaici. A huge termitarium (of the type produced by Macrotermes natalensis) with some mythical animals is depicted in northern Angola/southern Congo.

The identical map was included in four editions of the Geographia. So, how does one distinguish the different editions of the map that have been excised from their books? As is often the case with historical maps, the answer is off the map. The page headline above the map is the differentiating feature (there are also differences on the back of the page).

1522: ’ll Tabula moderna Aphrice’ - in a scroll

1525: no headline

1535: as above: ‘Tabv. Nova Partis Aphri’ – in scroll, as illustrated above.

1541: ‘Tabula noua partis Africæ.’

The maps by Fries are more commonly available in the market but are still quite scarce. I have yet to see a copy or image of the 1522 edition. I have a copy of the 1535 map for sale at the time of writing.

The tragic cost of advancing science

Publication of the Geographia, with its map of Southern Africa, was arguably the beginning of geography and cartography as sciences. As with all maps and the books in which they were bound, there are other perspectives. The advance of geography and cartography came at a heavy price: a tragic and macabre twist to the story of the Geographia.

The text to the 1525 edition of the Geographia was provided by Michael Servetus. He was a polymath, a physician and scientist, who had made a significant contribution to the understanding of human anatomy and physiology, most notably the circulation of the blood through the lungs (concluding that the lungs must have a special function).

Servetus also held heretical religious views for which he was condemned to prison on two counts, for spreading and preaching against the notion of the Trinity and against infant baptism. After having escaped from prison, he was recognised at a church service in Geneva and re-imprisoned.

John Calvin pleaded for Servetus to be executed by beheading. However, in 1553, he was burned alive at the stake outside Geneva… ironically, atop a pyre of books! ‘Servetus' ashes will cry out against him (Calvin) as long as the names of these two men are known in the world.’ (The Heretics, p 328).

The Reformation Wall in Geneva memorialises the reformists, including Calvin, who condemned Servetus to death. Thankfully, there is now also a memorial in Geneva to Servetus, the free-thinking physician and scientist.

Mémorial Michel Servetus

The 1535 map of South Africa by Fries has special personal meaning. I used to be a pulmonary physiologist and so, for me, the 1535 map is both a landmark in the mapping of South Africa and a memorial to Michael Servtus, a pioneering medical scientist.

For more information contact Roger - roger@africanamaps.com or https://www.africanamaps.com/

Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals. Roger represents the International Map Collectors’ Society in South Africa, and is chairman of the Bibliophiles in Cape Town, and of the Friends of the Cape Medical Museum.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.