Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Rodney Grosskopff, one of the architectural team that designed Ponte from 1970-75, looks back on his life and the story of Ponte. This article is based on a U3A presentation delivered in 2019. The piece was prepared for The Heritage Portal by Kathy Munro in 2023.

“Nothing you know about Ponte is true... In many ways the Ponte story is the Johannesburg story. Almost everyone you meet in the city has a tale to tell. Tales about it being a den of drugs, illicit sex, suicide, corruption and refugees - tales that perpetuate and polish the building's reputation as a makeshift ‘United Nations of criminal hit-men and whores'... but this 'the tallest residential skyscraper in Africa' and Johannesburg’s most notorious building, is just a building and for more than 4 000 people it is Home. I think Ponte is about breaking the prejudices we all have.” Ingrid Martens, filmmaker

“Ponte [is] a pivot of multi and overlapping transitions that hinge on it, from the Urban, economic, Political and demographic shifts around 1969... Ponte can also be seen as an expression of the pivotal Architectural element, its plan is a cluster of circles or as a Nucleus, as its shopping center was aptly called.” Hannah Le Roux writing in 'Ponte as A Pivot'

“Ponte speaks to a very Johannesburg condition. It has spoken to a city through cycles of decline and prosperity and decline and prosperity.” Melinda Silverman, speaking on a podcast compiled by Ryan Lenora Brown.

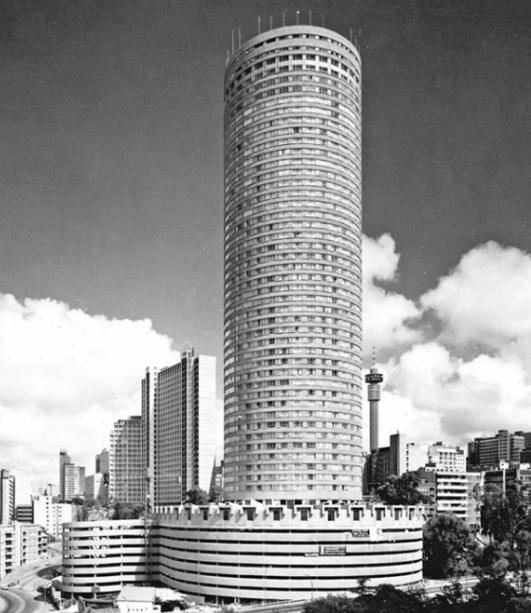

The clever things people say about Architecture always intrigue me. Fair Lady Magazine voted Ponte, 'The 2nd Ugliest building in the country', now people visit it like pilgrimage. I have heard it said that it is the most photographed building in the country.

For me it was a job, a job to which we gave our best shot, we worked hard on making it the best it could be for the value on offer, we always believed that we could add value and hopefully got it right more often than not.

Ponte at night, a glittering tower against the dark Johannesburg skyline

What was Hillbrow like before Ponte?

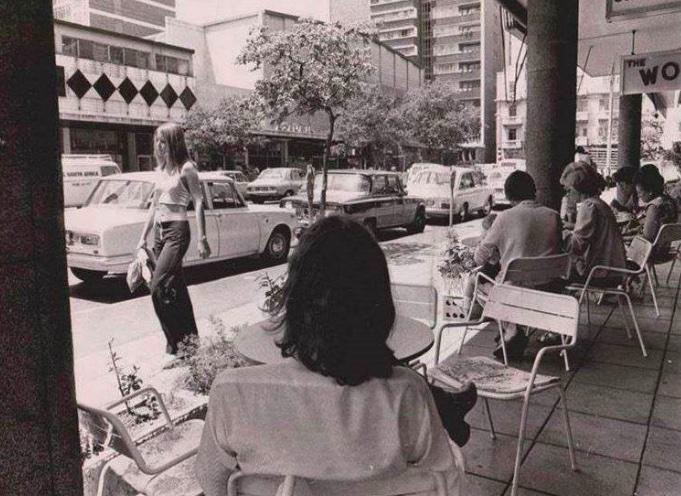

"Hillbrow was the landing place for European migrants. It was home to pubs and live music. Cafes like Bella Napoli, Café De Paris, The Florian and Café Zurich flourished. Here you could buy French magazines and Italian shoes and American Rock-and-roll. It had a shiny edge that people compared to New York’s Greenwich Village and London’s Soho.” Ryan Lenora Brown

Hillbrow was a place you could shop late into the night and find a meal after movies. It had highly sought-after accommodation for young and foreign residents; the demand was difficult to satisfy. Here too, the population was less comfortable with the racial dispensation in the country (Chipkin calls it 'a black zoning becoming grey') at the time and were more accommodating and it was here that racial barriers were being disregarded.

Hannah Le Roux in Ponte as a Pivot writes: “Ponte was designed at a particularly intense moment of change in Johannesburg and beyond. The intangible supports for urban growth accelerated at this time, so shaping an exponential leap in scale in the city upwards, outwards and in its density.”

This notion was punctured at the time by the 1976 Soweto Uprising. It is only with the perspective of hindsight that one can make these clever statements. We did not have the benefit of such an overview at the time, neither did we have any pretentions to change the world, nor did we have enough arrogance to guide the world into a new vision. But we did make a building that has become one of the most photographed in the country.

Pavement café on Kotze Street

Ponte from Westminster Mansions (The Heritage Portal)

Why a building like Ponte?

Frank Lloyd Wright once said, 'Great architecture needs great clients'. I am sure that he is correct; actually, I know he is correct.

I now invite you to contemplate: ‘Can great architecture make great clients?'. This case may prove it. We had some good clients for whom we designed some nice residential buildings: Norman Bank in Illovo perhaps half a dozen or so. Max Stein who was always proud of the fact that he owned as many blocks of flats as Mr Schlesinger in Killarney, and we did most of them. And Miodownik Development Company for whom we did so many buildings in Hillbrow and Berea.

Sanlam, the giant Insurance Company, started a Merchant Bank in the early 70’s which they called Mercabank and which in turn had floated off a Property Development Company called Nasbou. Its CEO Charles Ferreira was looking for a property which would broadcast their arrival on the Property scene.

Miodownik was hoping to convince them that Ponte was that scheme. It was that kind of building which needed a developer in that frame of mind. Nowadays there are very few residential buildings built for renting and certainly none of the size and stature as Ponte.

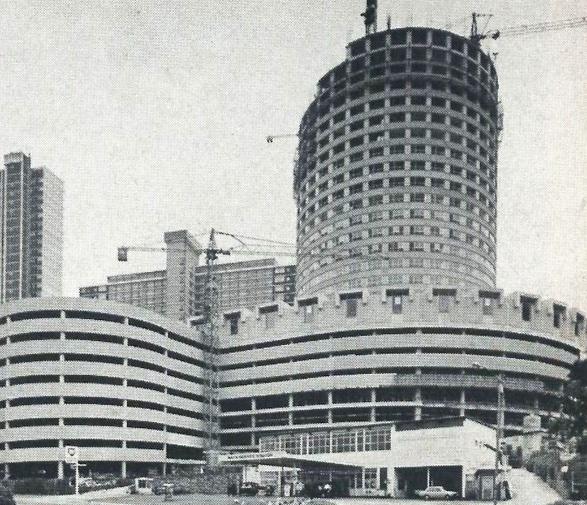

Ponte nearing completion in 1975 (GLH Archive)

We (GLH Architects) still design residential buildings such as The Emperor Apartments and The Regent in Sandton (which have both won awards) and The Tyrwhitt in Rosebank. These are all sold upfront on a deposit basis, which takes away much of the risk.

The Emperor Apartments (The Heritage Portal)

The Regent (The Heritage Portal)

When Ponte was conceived as a rental project, the developer had to finance the project until rents started to come in virtually at the end and took all the risks.

In those days South Africa had a burgeoning economy, as I said earlier the demand for accommodation was never ending, it was stable to the extent that escalation clauses were only introduced later, our money was strong. In 1980 when we went skiing we got US$1.3 for each Rand.

The new Johannesburg Technical College in Doornfontein (now a campus of the University of Johannesburg) was on the cards and would need an immense amount of accommodation on top of the existing demand. You could borrow money at 8%. This made Ponte an almost a blue-chip development and banks were anxious to lend or invest.

Who built Ponte?

The deal was done and MDC (Miodownik Development Company) and Mecabank got together to build the building for Nasbou. MDC was led by a powerful team: Max Miodownik, Ivan Block and Cyril Reid.

The Company was started by Max Miodownik Snr, a legend in the building industry. It was said of him that when he was handed tender documents of a building he would weigh them in both hands, shut his eyes, sway in a trance and in his heavy Lithuanian accent, predict the price. He was a man who brushed aside all opposition once he entered the site, resorting to his hip flask to cope with clients; dismissing architects as 'mere pen pushers' - a class sneer perhaps, contemptuous of the pampered, over educated scions of the rising middle classes strutting with self-importance on the building sites, their heads full of unpronounceable theories. (Source: Clive Chipkin, Johannesburg Transition)

Max Miodownik, the son and the successor to his father Max Senior, was the builder. Max Junior had much of the same drive and bravura, even though he was a qualified Quantity Surveyor. He left South Africa in the middle of the project, as an advisor to the Israeli Government.

Ivan Block was the business brains, and Cyril Reid, also a Quantity Surveyor, handled the costing and all money matters - each one an impressive talent but as a trio they were almost invincible. They also had some old-time building managers that had been with them from Max Senior’s time. Arthur Forbes was assigned to Ponte, a little bloke looking a little like Andy Cap, always wore a three-piece suite, a waistcoat, and a tie. A cigarette hung from his bottom lip. Certainly not a figure of fun, he puzzled out every aspect of the building and together with the Structural Engineer, Robert Erhlich, invented new ways to build, ways not yet tried in South Africa. Today, these methods are everyday practice.

The Design

As a young architect, I cut my teeth on Ponte, I toiled through its growth, I was there in its glory and squirmed with it, when it sank into disrepair, and I live with the hope that it will one day shine again as it was meant to.

I have often been credited as ‘The Architect of Ponte’, but anyone who has worked in a big architectural practice will know that it is seldom that one man is ‘The Architect’. It is usually a team effort.

I joined Manfred Hermer in 1959. By the time I became a partner in 1965, we were designing apartment buildings until they were coming out of our ears, in Illovo, Killarney, Berea and Hillbrow. It was virtually impossible to find an apartment there. As I mentioned earlier, Hillbrow was the closest we ever got to ‘Continental living.’

Every vacant site in Hillbrow was under investigation by us and I am sure every other architectural office. We could turn out a ‘Viability study’ in a morning, there was no escalation in cost in those days and the demand for accommodation was never ending. It was difficult to keep track of all the schemes and filing was a nightmare, so we gave them code names.

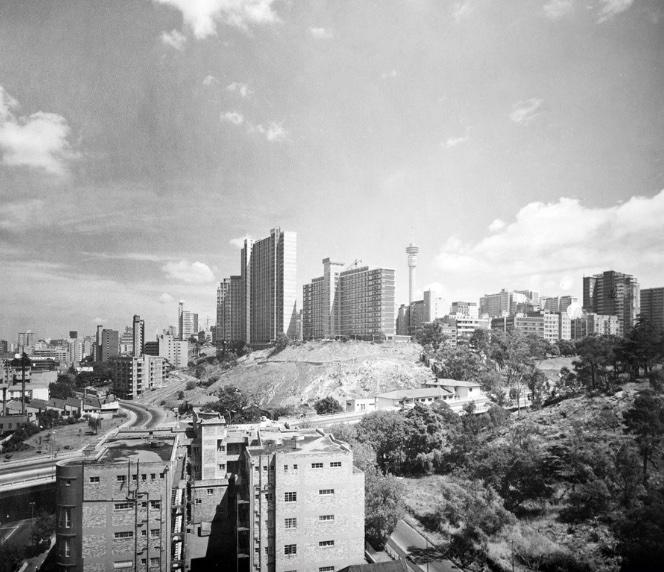

One day a curiously shaped site was presented to us. This steep site on Harrow Road (now Joe Slovo Drive) between Lily Street and Saratoga Avenue was owned by the Ponte family so we wrote ‘Ponte’ at the bottom of the plan until someone thought of something better. They never did.

When we computed out the Spatial Allowances on our site, we realised that we had a colossus of a building, and we would have to be very clever to get it all on the site.

An early photo of the site for Ponte. A steep hillside site defined by the Witwatersrand geology caught between Saratoga Avenue and Harrow Road (now Joe Slovo Drive). (GLH Archive)

An aerial view positioning Ponte between Saratoga Avenue and Joe Slovo Drive (Google Maps)

Then as now, apartments in Johannesburg need to face north, but our site was a queer shape and although it was large, it had a limited potential for north facing flats. At the same time, the planning authorities were trying to encourage slimmer taller buildings in Johannesburg, to allow the sun to penetrate the city and they offered benefits of more height in exchange for smaller footprints and greater setbacks from the street.

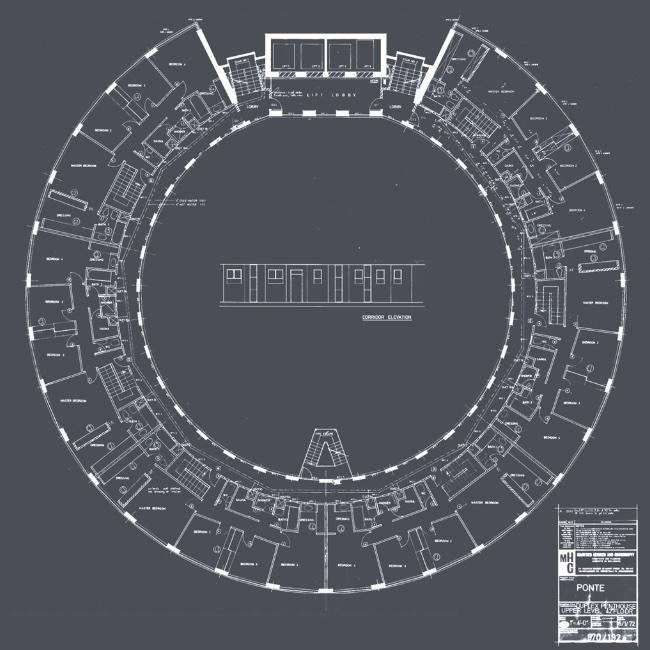

We laid out the building in the most optimal way that we could see and kept coming back to a round shape. Add into this the fact that Manfred had been hankering to do a round tower building for some time. This one was large enough so that the internal spaces were not excessively wedge shaped. There was a law at that time, that all residential spaces (which included kitchens and bathrooms) had to face onto natural light, which generated a large tube, this shape bounced back at us repeatedly. It was structurally sound.

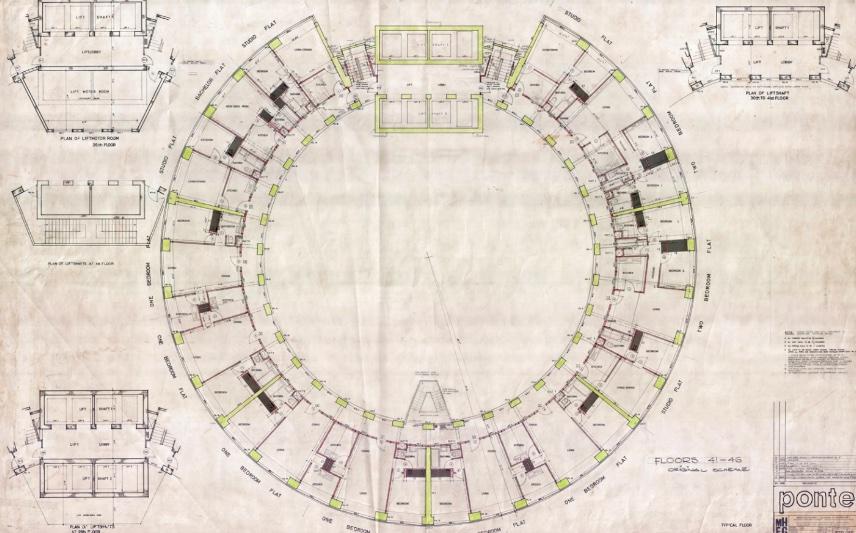

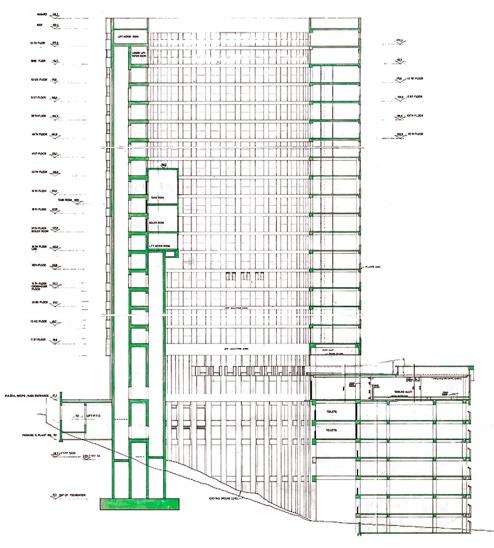

Layout of a typical floor (GLH Archive)

At the time in England, there was a kick-back against giant highrise apartment blocks from a security point of view; they became so dangerous that many of them have since been imploded. We felt that a tubular form offered an internal corridor from which one could oversee the approaches to literally dozens of flats; those below and above your floor and on either side, we believed it was a defensive space. Add that to the logical development of the layout and we remained intrigued by the shape. It had never been done in Johannesburg before.

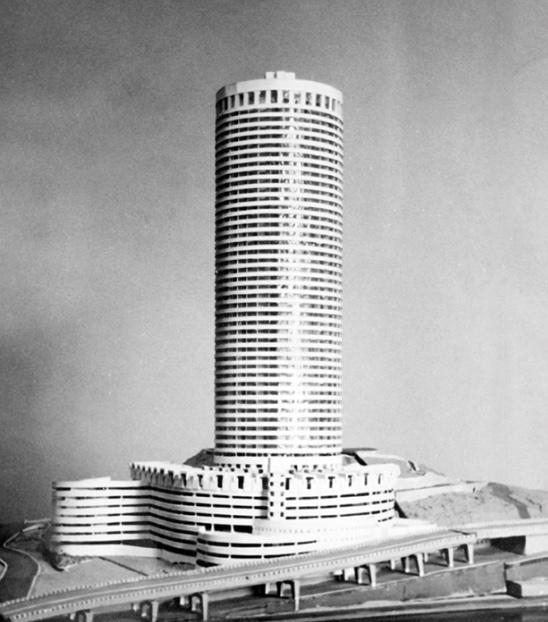

Working Model of Ponte - Arthur Forbes (GLH Archive)

On the side of Harrow Road, it would be like a beacon at the edge of ‘Town’. We were also looking at the nearly similar site on the hill on the opposite side of the road. If it worked for one side it could work for the other. Imagine leaving town between two 50 storey round towers!

Parking needs

Whilst we were working on the tower, we were always aware that we would need plenty of parking and the site had some shopping rights as well. We could see a self-standing living unit; shops, offices, perhaps a crèche. With a population of a small town the possibilities were endless.

Once again, the logic came first, the parking naturally generated a layout hugging the base of the tower. There were two entrances for cars, one from Saratoga Avenue at the bottom and the other from Lily Avenue some seven storeys higher up the hill. It was further logical to place the shopping centre on top of the parking, level with Lily Avenue and Hillbrow and so the base wrapped round the tower in a great snail shell.

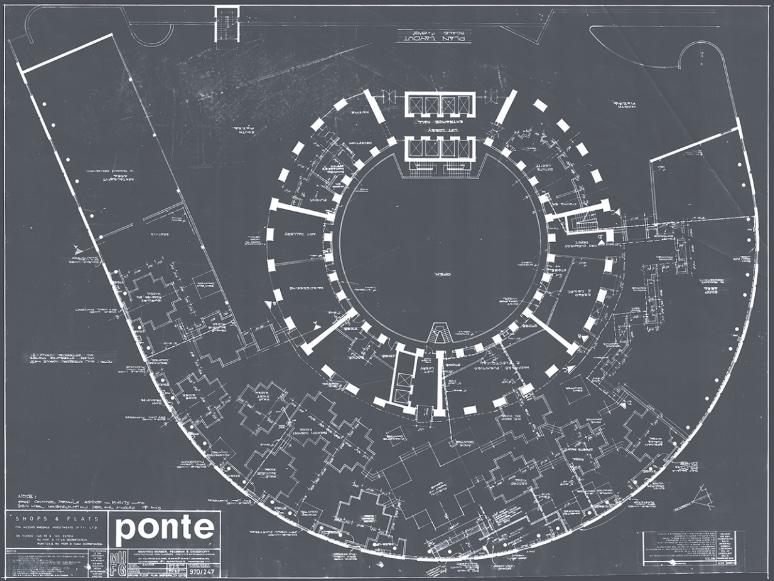

Parking garage plan (GLH Archive)

View of Ponte from the parking garage (The Heritage Portal)

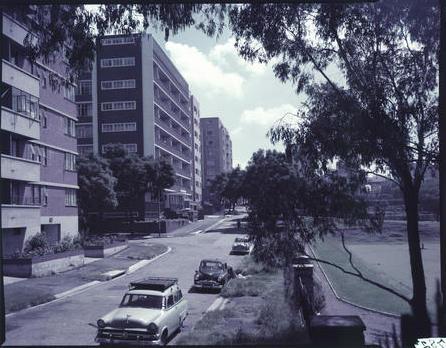

Lily Avenue, Hillbrow (DRISA)

The sums stacked up and our client Miodownik Development Company was ready to go. Once Nasbou came on board, a marriage was forged and work began. At this time Mannie Feldman joined the practice and he added his immense talent to the amalgam.

We all subscribed to the tenets of the Bauhaus movement, ‘Form following function’ - Manfred, at its earlier gentler beginning, Mannie, the brutal mainstream, and I, fighting off the brutal extremes at the other end of the movement. We all had a hand in its final form, brainstorming late into the night, week after week.

I suppose Mannie’s baby was the shopping centre, particularly the roof over it.

The Shopping centre plan (GLH Archive)

My focus was the tower and parking garage and Manfred the business side of its birth. Robert Erhlich the structural Engineer, and Arthur Forbes, the Contractor’s site manager (both of whom are seldom mentioned), played a massive part in the design of the final product. We were in a continual ‘arm-wrestle’ with them... what would stand-up against what was feasible to be built – all from the inside. In our corner, we were fighting for a sustainable, attractive and permanent building and they fought for stability and buildability.

After the design was in the can, Mannie left the practice.

I was the Architectural midwife, wet-nurse, and fairy godmother, finalising the design, the detailing and supervising its construction. I suppose this is why I am remembered more than the other great architects associated with this iconic building.

Viability

The figure of R10 500 000 to build Ponte was bandied about but you could borrow money in those days at 8% and the more units you could put on the site the better the return. Bachelor flats gave the best return, three-bedroom flats gave the worst with one- and two-bedroom flats in-between. However, it would be suicide to have too many bachelors because they were the most mobile tenants and that in itself was a cost, whereas three bedroom flats were more permanent and a good financial backbone. So, we had a spread of accommodation on each floor and rearranged it on the upper floors to make up just less than 500 flats in all. At the time the return was from 10.29% to 10%.

Typical floor plan (GLH Archive)

The height of the building was a simple calculation: each site in Johannesburg had ‘a bulk factor’ (now a F.A.R.-Floor Area Ratio) and envelope of space you could build within. Once we divided the footprint into the area we had available, we had the number of floors. However, there was a further ridiculous law in those days; you could have some more free buildable area for servants rooms provided you put them on the roof and had only small windows high up on the walls with no view. That added a few more floors.

Tube volume (GLH Archive)

There were other vagaries in respect of the height. The controls of elevators were less sophisticated then, one bank serving about 16 floors was optimal. It could be stretched to 22, thereafter another set of elevators was required, so we were in the two-bank category in any event. It did not particularly matter if you speeded up the travel because the biggest delay was in the opening and closing of the doors. Nowadays, elevators have clever electronic controls so that only one lift in the bank responds to a call, but at that time they all raced to your aid, some coming second and third and all going to the trouble to open their doors to find you gone.

Positioning of the lifts (GLH Archive)

The founding material, except for a fault which our engineers repaired, was rock solid and not an issue, whether we went 50 or more storeys.

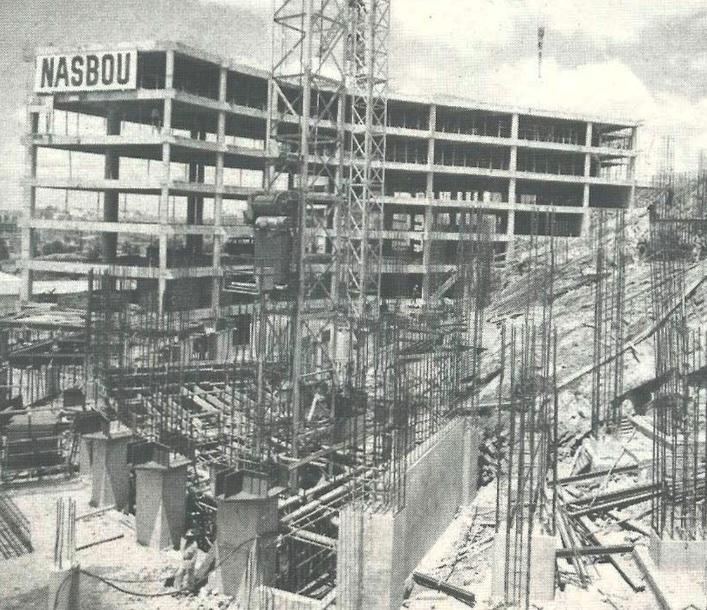

Ponte Tower under construction (GLH Archive)

We found beauty in the honesty of raw concrete; it was and still is a hard-working material, one you could rely on. Arthur Forbes devised a clever system of shuttering, nowadays everybody uses it, then it was new! He had massive tables made with dropdown sides on adjustable legs and wheels. He simply lifted the tables onto the floor, folded out the dropdown sides, adjusted the heights and cast the slab. We were mindful that our shutter hands were not the best in the world, so the exposed faces were hacked rough whilst the concrete was still green to hide defects and wait for the weather to coat it with patina over time. The edges of the tables were the only scaffold we had, and it had to be used before going up to the next floor. Everything else was done from the inside.

Ponte under construction - parking garage and the next few levels (GLH archive)

The Construction

The construction phase was unspectacular in many ways, but there were some interesting differences because of the height.

I suppose everyone thought of the difficulty of getting materials and workmen to the workface but none of us had any firsthand experience. Arthur Forbes did some homework. His plan was to have two construction lifts for personnel and small equipment and three cranes for the big material - it was the biggest headache. The construction lift was a rickety affair in a scaffolding frame and shook from side to side as it cranked its way up. It was closed in with steel mesh, the wind howled through and it was scary as hell, shaking past bits of unfinished building, seeing the ground disappearing beneath your feet. The worst thing about it was the interminable queues, long waits and of course overcrowding.

This of course brought about all sorts of problems. Here is one little story which tells it all. I had one privilege which was to use the construction lift for an hour on Sunday mornings, my excuse was that I needed time to review the work. I used it to do that, but on occasions to take friends and family around the site. On one of those mornings, I took some of the young staff for a jaunt and on one occasion, a young trainee architect, 'ooohed and aaahed' and declared that she loved the smell of fresh concrete and to underline it took deep breaths of the air. All we could smell was pee and dagga.

We had buckets on every third-floor landing, often overflowing. We also had mad labour laws in those days - only white men could ply the building trades, but we had some very accomplished black tradesmen who would have to make themselves scarce if there was an inspector around or for recreational purposes would find a quiet corner and enjoy a little zoll (hand-rolled marijuana cigarette). These two combined to create the heady aroma of fresh concrete.

Eating was pure madness because it would take the whole of lunchtime just to get up and down, so we had three temporary canteens and spaza shops (informal store) on various floors.

Hoisting materials was a challenge - then we called it a 'balls-up!'. Everything had to find its way to the top somehow. We had three cranes and they spent a lot of time getting in each other's way.

We also had an exacting structural program of casting a concrete deck every two weeks - come hell or high water. If you lost a day, it cost you a week!

Let me elaborate: Monday morning work would begin on the cleaning up and the column shuttering for the next floor and they had to be cast by Friday. Then, on the following Monday, the slab shutters were lifted from the floor below and placed in position. They were designed like several gate leg tables with drop down sides. Once in position, the sides were lifted, linked together, and adjusted to form one massive deck. This was completed by Tuesday night, Wednesday the latest. The reinforcing and services blokes would then do their work. On Friday the concrete would arrive and be placed. If you missed the two weekends of setting time you lost a whole week.

Because the structure dictated the whole timetable, it took preference over everything. That meant that the cranes were basically available for only 7 of the 10 days in each fortnight and the fight for crane time amongst the other trades often broke out into open warfare. Trades would bribe their way up the queue and they would sabotage the delivery trucks of other trades.

Utopia Finally got built

Below are a few extracts from a 1973 brochure (appearing in Ponte City by Norman Ohler). This is how Ponte was advertised and in many ways it was true.

Ponte City. A residential dream comes true.

The 54-storey apartment tower within view of Johannesburg’s bright city lights sets new standards worldwide. It is the ultimate in chic and sophistication.

Yes indeed – All of a sudden there is excitement in the air! You get carried away by the exhilarating feeling of immensity.

All this has been made possible by people who are able to look beyond mundane everyday needs in planning Ponte City.

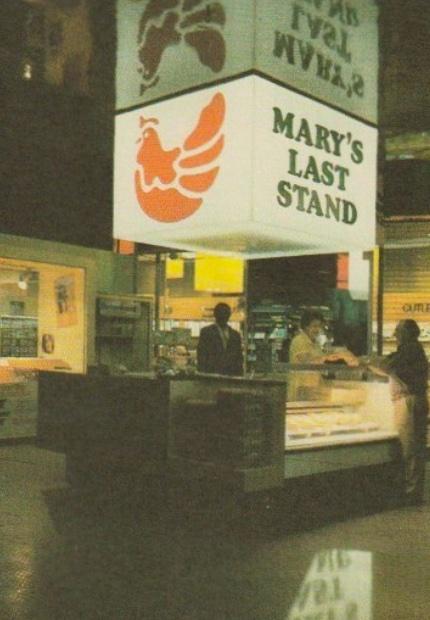

You drive into the generous parking garage for 2000 cars, to be precise spread over 7 floors connected by several lifts to the shopping malls.

No traffic noise or inclement weather, but elegant boutiques, a hairdresser’s salon, a discotheque, a bank and even a supermarket! From here you can take one of the eight ultra-modern lifts - travelling at a speed of 400 meters per minute - up to the Ponte apartments. These are, of course, exquisitely furnished and equipped. In the Penthouses for instance, even the toilets are fitted with telephones.

South Africa can be proud of its Ponte City. Equal to the greatest apartment complexes in the world, it is virtually a city within the city of Johannesburg.

Really that was the goal and, in many ways, it was so!

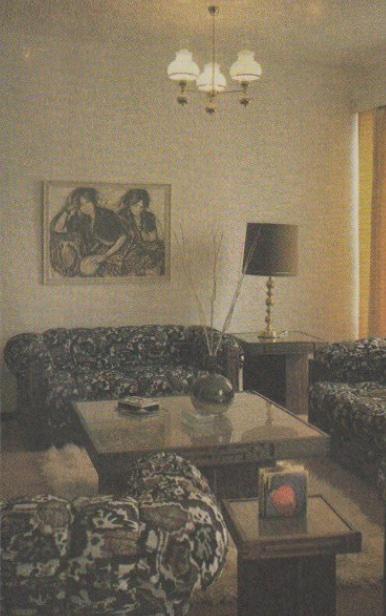

The flats were beautifully furnished and as predicted, fully rented in no time. The massive demand is enough proof that at least part of the dream came true.

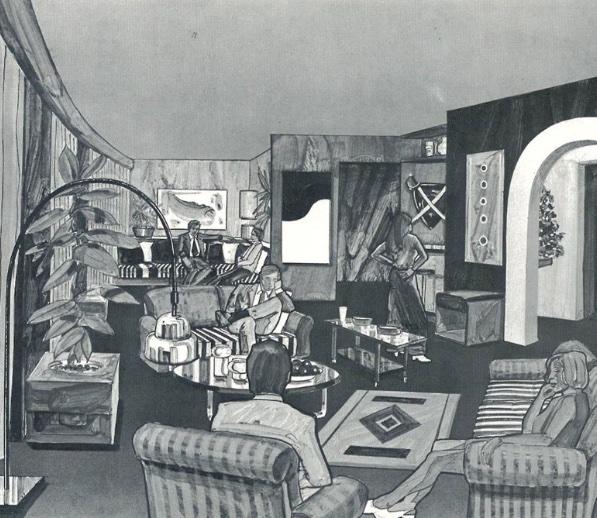

Interiors in the 1970s (GLH Archive)

Oriel Alby, as a young curate at the Johannesburg Cathedral, told me that he regularly visited two of his congregants who were living there in 1975. A Swede and a young black girl whom he married in the Cathedral. Ponte was new, crisply clean, and abuzz of ‘Happily ever after’. There was no fuss about a mixed couple living together that he could see and he really thought Ponte lived up to its billing.

That dream was very different to the one we are holding up to the mirror today. In the original planning, we did not imagine that the Shopping Centre would be anything more than a service for the building’s own inhabitants.

Then there was no Uber eats or grocery delivery that we have today.

We sensed that residents from nearby buildings would use its facilities but made no provision for an external easy entrance to the shopping area nor offered a convenient proximity to the parking. Back then we did not have security access to any residential buildings, nor did we need it.

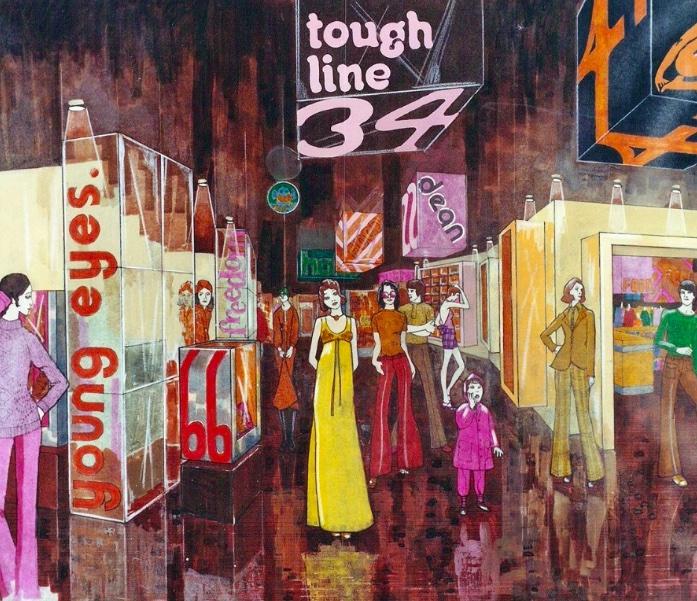

The shopping centre they described in the 1973 advert, quoted above, was the one we designed, even though there is no mention of the restaurant and central court. I honestly believed it would have lived up to the promise. However, shortly before the completion, the owners had a rush of blood to the head and decided to consult D.I. Design, the Canadian shopping centre designers who had just finished the incredibly successful Sandton City. Their Stewart Chayes suggested a throbbing market of tiny shops; the clients went for it boots and all.

The entire beautifully articulated, light-flooded, concrete roof of which Nervi would have been proud was covered with a chocolate-coloured ceiling. All the light was cut out and all the windows closed in. Tiny little shops, all about 10 m2 were dotted around.

Interior render drawing (GLH Archive)

Mall interior (GLH Archive)

It looked good and might have worked in Canada but not in South Africa, certainly not in Johannesburg and decidedly not in Ponte. They tried everything to vitalize it to no avail. The Nucleus (the name of the shopping centre) worked for a few months until the novelty wore off. It was removed and a bowling alley worked for a while, so did the Discothèque, but to no avail.

Our design was directed at the residents of the building: convenience shops at low rentals, a restaurant on a central court overlooking the city and service providers in a light flooded area.

The new fairytale cost a fortune, which necessitated higher rentals and importing thousands of outside shoppers undermined the security and the cozy neighbourliness of the Dream. It did not work and I suppose it undermined the greatness of the residential unit to an extent, but I don’t think it was the only negative factor.

Reality set in

At the beginning, I pointed to the widespread belief that Ponte depicts in many ways the transition of Johannesburg itself. Clive Chipkin talks of the black and white of apartheid turning gray in Hillbrow and Ponte. I have also spoken a lot about the massive demand for accommodation in this area. That was a reality! The Social demography of Johannesburg was changing.

South Africa and Johannesburg in the 1970s had one of the strongest economies in the world. At that time the Rand had an exchange rate of 1-1.3 to the US$.

Charmaine Naidoo writes the stories of people flooding into Johannesburg like a human tsunami. She tells the story of the Ethiopian, Samuel K. When the 28-year-old soldier learnt of the slaughter of his family by the rival Oromo tribe in his hometown of Tigray he headed south. He took 69 gruelling days to walk or cadge lifts, carrying nothing, to reach South Africa and safety. Sammy is one of the hundreds of the thousands of 'illegals' in South Africa. He said, 'People in my country call it a shining beacon in the darkness.'

She tells the story of the Angolan, Jose aged 34, a surgeon who fled Luanda with his pediatrician wife, Aurora, and their three small children. They escaped with the help of the Catholic Church, after Government troops burnt down their home. Jose was anxious to work, prepared to do anything and began working in the informal settlements and hostels. He and his wife and three children were sharing a one bedroom flat with seven people until they found Ponte.

Landlords were getting more and more used to the idea of renting to African tenants, despite the Group Areas act preventing it.

Many people were ready to live in overcrowded conditions - anything for a roof over their heads. Unscrupulous landlords were ready to fleece them but they in turn were overwhelmed by the thousands of tenants, fighting back by refusing to pay rents.

Properties owned by responsible landlords had their hands full. Many landlords simply walked away from the problem and left the country. This led to lack of maintenance and a degradation to the fabric of the building.

Even though not to the same degree in Ponte but the pressures were there. It was the biggest and most iconic building and stories from anywhere in Hillbrow were grafted onto Ponte’s C.V.

Norman Ohler’s book Ponte City describes life in the building. He claims it’s fiction, but quotes newspaper articles and police reports. He describes meetings of drug lords on the 39th floor; police raids and guns being seized. Add to that the degradation to be seen everywhere in Johannesburg. All the stories of suicides and sin became vividly real.

It was already being called Little Kinshasa. Lizeka Mda wrote that this was the only place you could hear Kwasa-Kwasa. Bongonie Madondo tells us he often went to listen to the bands from Zaire and their throbbing rhythms originating in the speakeasies and dark alley joints of Kinshasa.

The start of the bailout

By 1981 the original owners were trying to get out and there were many attempts to sell apartments. The Sunday Express of 3 May 1981 announced the sell off. Three Bedroom flats at the top of the building were priced at R99 000. A penthouse could be snapped up at R250 000.

Then there were ugly stories of evictions in the press. It was not a great success. In The Citizen of 2 January 1982, Dr Charles Ferreira reported 'I only said that we would not accept less than R22-million for Ponte' and that if he was the sole decision-maker 'Ponte would never be sold.'. But the sales talk carried on. There were other hair-brained schemes such as one idea of turning Ponte into a Prison!

The giant signs for Coca-Cola and later Telkom, lit up the night sky in neon and those adverts were as famous as the building itself. The advertising sign was a beacon that could be seen from Midrand as one approached Johannesburg.

The framework on top of Ponte for the flashing billboard (GLH Archive)

Finally, Ponte was sold to the Cottrell family (the Kempston Group) in about 2000. They took a firm grip on it. They introduced secure access and limited occupancy to one person per bed. They put Ponte on a path to a semblance of recovery. It was a hard fight to win. There was a vision and a new opportunity, but one can hardly blame them for being discouraged and a few years later they were ready to sell.

Rubbish inside the core (Archinect)

Back to basics... the rubbish cleared

In 2007 David Selvan, who started Kaya FM, and his Moroccan partner Nour Addine Ayyoub bought Ponte from Kempston. There was a great flutter in the press. Nour even abseiled down the building as a publicity stunt; they reputedly paid R110 000 000 for the building and spent R30 000 000 on refurbishing flats and creating show apartments.

I was consulted in the beginning but pulled out because I really thought their budget was too low; I thought it should have been more than double. I hoped that Selvan and Ayyoub could pull it off. They were not babes in the woods; they had already refurbished and sold off a few buildings in Braamfontein, Berea, and Hillbrow and done well with a nice product.

The Sunday Times (11 November 2007) reported that 80% of the newly renovated Flats were sold. Then came a few negative reports and finally we read in the Financial Mail that Tony Cottrell was cancelling the sale due to non-payment. There were rumours that Selvan and Ayyoub did not have their ownership paperwork in order.

The light at the end of the tunnel

Michal Lupcik (call me ‘Loopy’) (previously an accountant with Price Waterhouse Coopers) and Nicholas Bauer (a TV journalist), two delightful Hippies, moved into Ponte in the early 2010s and loved it - warts and all. They started out with a tour operation which they called Dlala-Nje – ‘Let us play’ in Zulu.

Lupcik and Bauer saw a beauty and verve in Hillbrow, they enjoyed the colour and sound of Africa and were happy to show Hillbrow and Joburg to overseas and local tourists alike. They were proud enough to treat their customers to the tastes of Africa, always bringing them back to Ponte. Their venture soon became one of the busiest tour operations in Johannesburg.

These two young men wanted to ‘Give back’! They ploughed back part of their profits into the Dlala-Nje preschool / care center for the Kids of Ponte. Sam Varney joined them at the care center and under her enthusiastic guidance, it grew to be an all-day center for more categories of young people. The Cottrell family took them to their heart and were happy to follow this the path with enthusiasm. They made the Penthouse 5101 available to Dlala Nje as a clubhouse for the tourists. It was redecorated in a sensitive but fun African style. The bar stools are made of beer crates tied together with cable ties. The cushions are covered in African print fabric and the tables are covered with flattened pilchard tins.

View from Penthouse 5101 (The Heritage Portal)

Memories being shared at Penthouse 5101 (Diana Steele)

The food is eaten with your fingers but rinsed frequently in a communal basin in the middle of the table. The bar is clad in galvanized iron sheeting and the nibbles are displayed on plastic plates like the pavement stall ladies use to display their fruit. The decorations are ‘Urban African’ hair style posters and adverts.

For me, the most exciting thing was that they re-found my earlier vision for the shopping center. They ripped out the ceiling revealing (after 35 years) Manny Feldman’s incredible 'cathedral of light'. They are putting the shops back as we originally imagined.

It is still a work in progress, and I sincerely hope they will revive this grand and noble building.

This article is based on a 2019 talk delivered by Rodney Grosskopff to a U3A Group. It has been updated by Kathy Munro for publication on The Heritage Portal.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.