Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We as a family are very proud of what Magdalene Morse-Jones has achieved with this work. Thanks to her research we now know about our family roots. The first part of the story looks at our ancestral home, Hohenzollern Castle in Germany (then Prussia) while the second reveals some of our early family history. The third and fourth parts trace the beginnings of the South African wool industry and highlight the contributions of the Shuman Family. Click here to read the original pdf article. (William Shuman)

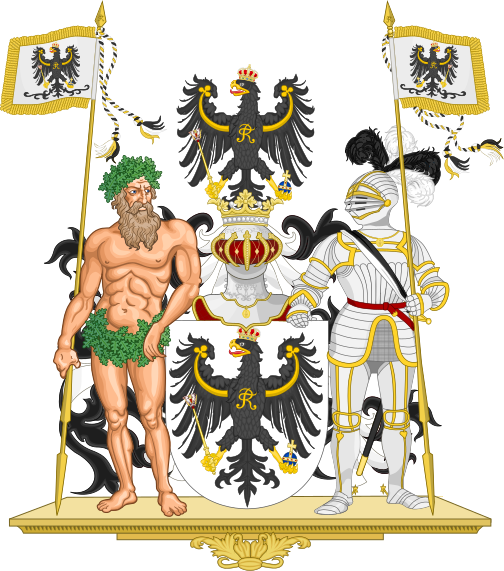

The wild men are mythical figures that appear in the art and literature of medieval Europe. The image of wild men survived to appear as part of heraldic coat-of-arms, especially in Germany, well into the 16th century.

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. It was the driving force behind the unification of Germany in 1871 and was the leading state of the German Empire until its dissolution in 1918.

Kingdom of Prussia Coat of Arms 1871–1918

Hohenzollern Castle is the ancestral seat of the imperial House of Hohenzollern. The third of three hilltop castles built on the site, it is located atop Mount Hohenzollern, above the edge of the Swabian Jura of central Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Hohenzollern Castle (Wikipedia)

Frederick William I, King of Prussia from 1713-1740 (Wikipedia)

Hohenzollern Castle - A Legendary Gothic Fortress

The first personal related reference of the Hohenzollern House dates back to 1061 (‘Wezil et Burchardus de Zolorin”). The first direct mention of the Castle complex (“CastroZolre”) was in 1267. Appearance, size and furnishing of the original Castle are unknown, but presumably it was in the first decade of the 11th century. At that time it must have been a vast and artistically valuable furnished complex. Contemporary sources praised it as the “Crown of all Castles in Swabia” and as “the most fortified House in Germany”. However in 1423, the Castle was completely destroyed.

From 1454 the second Hohenzollern Castle was constructed on a larger scale and was more fortified. Later, during the Thirty Years War, the Castle was converted into a fortress with repeatedly changing owners. Since the maintenance of the building was neglected, it became dilapidated at the beginning of the 19th century.

In 1819 Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia decided to have the ancestral seat of the Hohenzollern House reconstructed. In 1844, now King Frederick William IV, he wrote in a letter:

The memories of the year 1819 are exceedingly dear to me and like a pleasant dream, it was especially the sunset we watched from one of the Castle bastions, ... now this adolescent dream turned into a wish to make the Hohenzollern Castle habitable again...

From 1850 he put his long lasting dream into reality and created one of Germany’s most imposing Castle complexes in a neo-Gothic style. With its many towers and fortifications, it is an acclaimed masterpiece of military architecture in the 19th century. Additional civil architectural elements make it a unique attraction. The location on the most beautiful mountain in Swabia, gives the Castle a picturesque appearance.

Aerial view of this majestic castle (Wikipedia)

From 1952 Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia furnished the castle with valuable works of arts and significant historical artifacts pertaining to Prussia and its Kings. In addition to paintings from renowned artists (Honthorst, Pesne, von Werner, von Lenbach and Laszlo), there is a display of gold and silversmith works from the 17th to the 19th century.

In 1970 and 1978, earthquakes caused immense damage to the Castle. Now and in the future all costs for maintenance, preservation and renovations have to be financed from the admission fees. The Castle complex presents itself to visitors from all over the world, being well maintained and in perfect structural condition.

The Prussian Crown Jewels are the royal regalia, consisting of two crowns, an orb and a sceptre used during the coronation of the monarchs of Prussia from the House of Hohenzollern. After the King of Prussia became German Emperor on establishment of the German Empire on 18 January 1871, they were no longer used as the position of King of Prussia while still remaining, was a title of lesser importance compared to the new role as German Emperor. There was no crown for the German Empire, although a heraldic version existed.

Crown of William II (Wikipedia)

Atop a foothold of the Swabian Alb mountain range, the House of Hohenzollern stands over the trees in an image that seems to have leapt from the pages of a fairy tale. The castle has 140 rooms in total, with highlights including the library with its incredible murals, the King’s bed chamber, a family tree room and the Queen’s room known as the Blue Salon. The interior design is splendid with its gilded coffered ceiling, stunning marquetry flooring and portraits of Prussian royals.

Straight out of a fairy tale (Wikipedia)

Ancient Schumann Family History

The original Schumann families, owned large estates where they were mainly cattle farmers and hunters. They spoke a language belonging to the Baltic group of the Indo-European language family. The Schumanns and other Prussian families were related to the Latvians and Lithuanians, who lived in tribes in the then heavily forested region between the lower Vistula and Neman rivers. Their social organization was loose – although some elements of stratified society can be traced – and they were pagans. Early attempts to convert these Prussian clans to Christianity – notably those made by Saint Adalbert and Saint Bruno of Querfurt at the turn of the 11th century – were unsuccessful. In the 13th century, however, these Prussian tribes were conquered and Christianized by the German-speaking knights of the Teutonic Order, which had been awarded Prussian lands by the Polish Duke Conrad of Mazovia for help against Prussian incursions. The Prussian countryside was subdued, castles were built for the nobility, and many German peasants were settled here to work on the Schumann and other families' estates. By the middle of the 14th century, the majority of the inhabitants of Prussia were German-speaking, though the Old Prussian language did not die out until the 17th century. By this time the indigenous population was thoroughly assimilated.

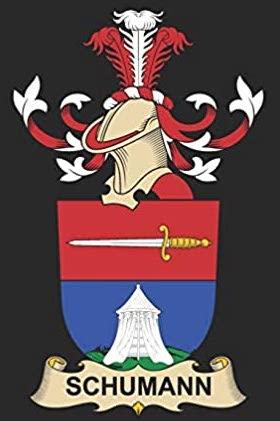

The Schumann Coat of Arms was used primarily to establish their identity in battle. It consists of a shield displaying charges (the emblem occupying its field), accompanied by a warrior's helmet, the mantling which protects his neck from the sun (slashed fancifully to suggest having been worn in battle), the wreath which secures the mantling and crest to the helmet, and the crest (the device above the helmet). A family symbol which has been passed down through generations.

Schumann Coat of Arms

William Shuman was raised by his grandparents, Uriah and Johannah Dicks, who did not want a German surname for their grandson. In 1873, they omitted the preposition “von” as well as the “c” and second “n” in Schumann, now called Shuman. As a result of this change, the prestigious title of “Baron” became obsolete.

Ernest Shuman (1901-1979) & William Shuman (1904-1952). Sons of William Arthur Shuman.

William Arthur Shuman

The South African Wool Boom

In the early 19th century wool replaced wine as the Cape’s staple product and its most important export – and in 1840 London wool brokers began to speak of “a large and valuable export” from the Cape. The value of the wool depended on such variables as quality and the ruling price at the quarterly sales on the London market, but apart from occasional setbacks, prices generally rose each year until 1860, earning an impressive £286 000 by 1851 – 59 percent of the revenue from all Cape exports. Predictably, the boom attracted a new type of immigrant from England and elsewhere in Europe after 1840. He had plenty of money and was keen to invest it in sheep farms. In an effort to lure this wealth to their districts, towns and villages in the colony competed with one another in order to attract investment and soon pamphlets and newspapers were trumpeting the appeal of one area over another.

Among the most important of these merchants were German immigrants Maximilian Thalwitzer, the two Mosenthal brothers – Adolph and Joseph - as well as Wilhelm Schumann.

Thalwitzer provided an indirect spur to wool production in the early 1830s by acting as an itinerant wool buyer in the Western Cape’s sheep country. He became more directly involved after 1840 when he hired a ship to import merino sheep.

The Mosenthal brothers opened a branch at Port Elizabeth in 1842 as part of a rapidly spreading network designed to eliminate the collection problems resulting from poor communications. They established a chain of stores and agencies throughout the eastern districts to which farmers could bring their wool.

In his capacity as a nobleman, Wilhelm Schumann encouraged German investment in Cape Wool, and it was through him that the Hamburg brokers “Lippert and Co”, built up a lucrative connection as wool importers.

Not all merchants confined themselves to the role of middlemen: they also became financiers and bankers to the first generation of Eastern Cape wool farmers. When times were tough, they provided the credit without which their clients would have gone under. So secure were they that their notes began to circulate (these were drawn on their Cape Town offices). When this practice was abandoned, the merchants joined the board of banks. There was a mutually beneficial relationship between farmer and merchant that had a major impact on the area’s economy.

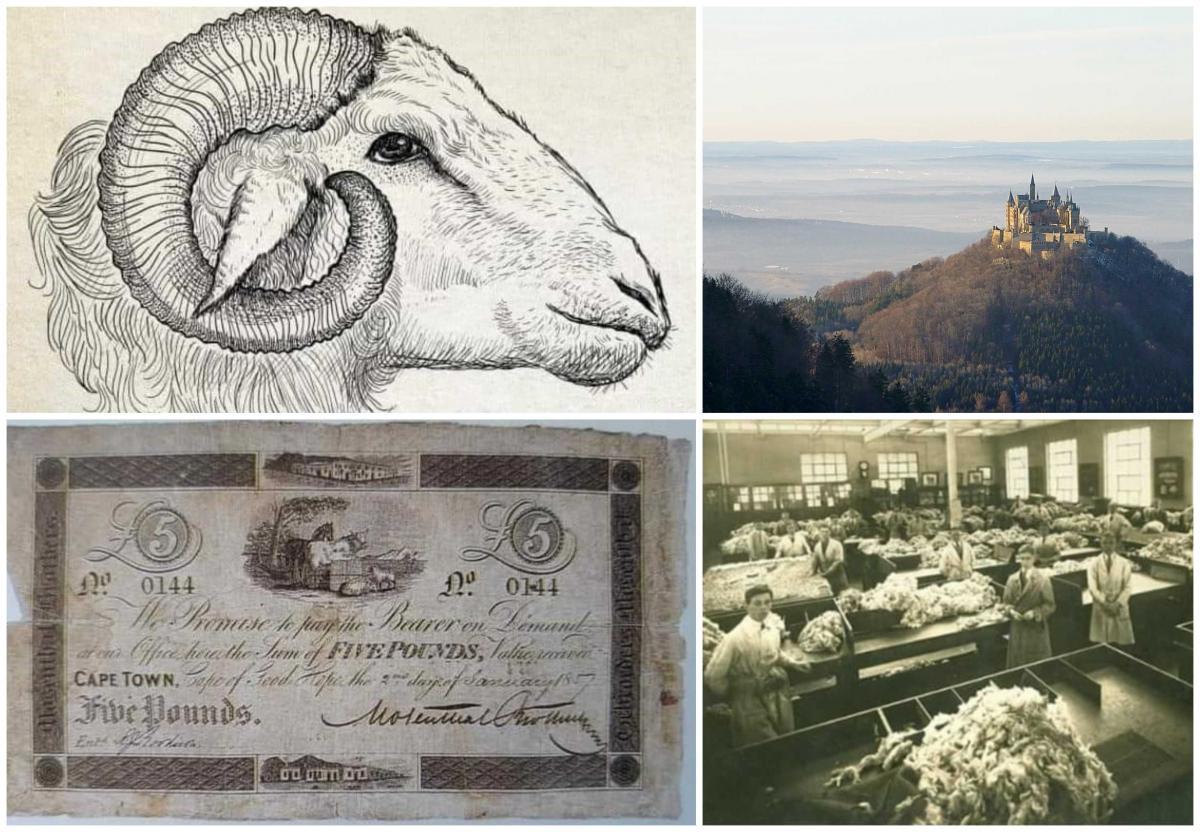

Merchants issued bank notes

The “golden fleece” revitalised the Cape’s sagging economy in the 1840s and 1850s. Merchants fanned out across the Eastern Cape, selling bloodstock and buying wool clips for shipment to the textile mills of northern England.

At the forefront of importation were the merchants who introduced French merino sheep to South Africa in 1852. The new blood brought great advantages, leading them to play an extensive role in improving the quality of the product and ensuring better prices.

French Merino Rams

Wool being sorted into grades at Mosenthal’s by individuals who had developed a keen sense of touch. The same quality wool obtained from the fleeces of a large number of sheep were then mixed together in preparation for the export trade.

The world’s demand for wool was growing rapidly. From 1840 to 1860, shipments from the offices of Mosenthal’s in Port Elizabeth increased twentyfold, largely as a result of their efforts. They will always be credited for the creation of South Africa’s wool export industry.

Mosenthal Brothers signalled ships

A Pioneering Wool Baron

Baron Wilhelm Karl von Schumann is the great ancestor of the Shuman families, who today farm in the Queenstown district. He was a nobleman who emigrated from the German Kingdom of Prussia to South Africa in 1855.

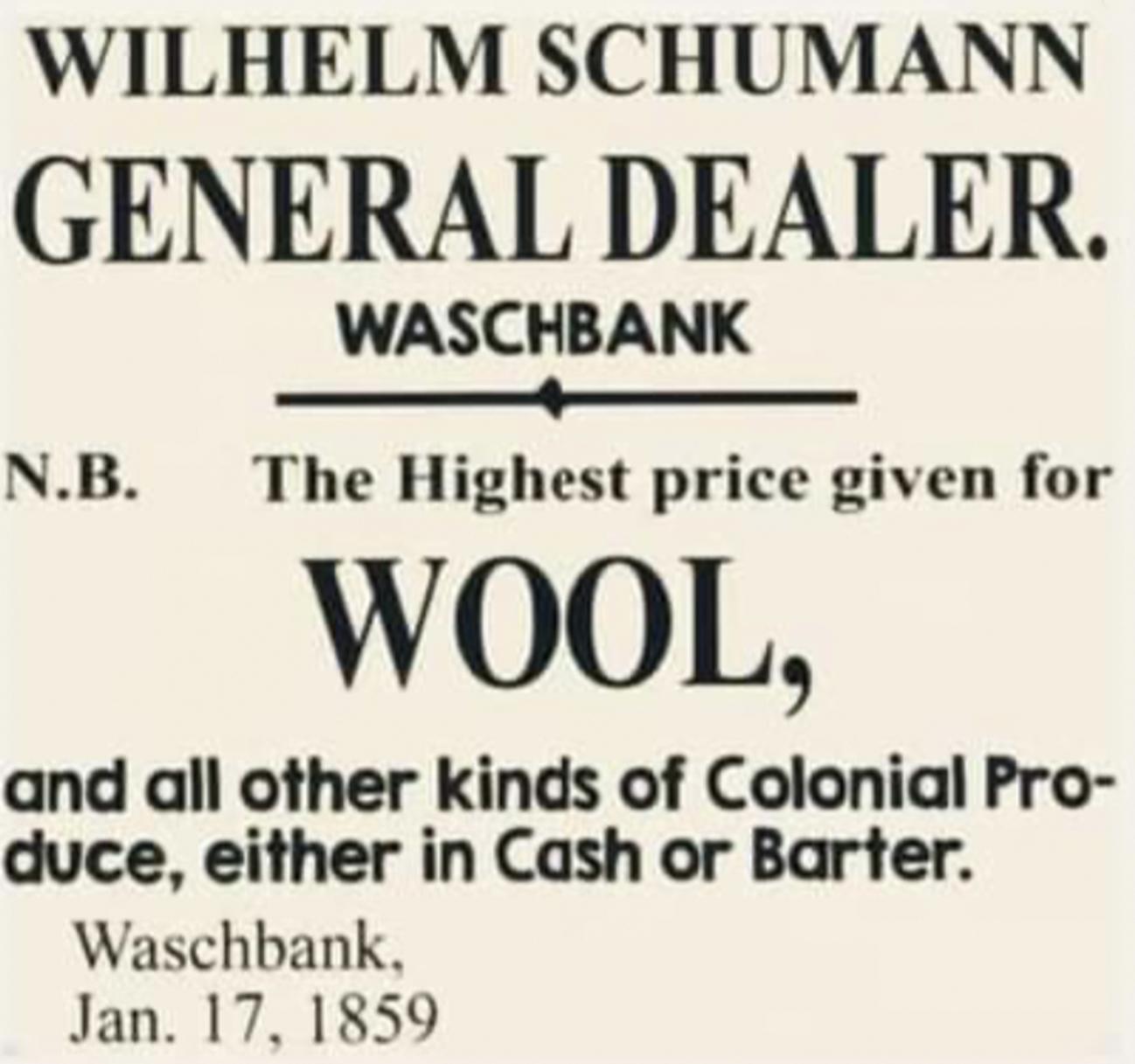

Wilhelm purchased the farm “Wasche-Erdwall” (named by him) in the Wodehouse district between Dordrecht and Elliot in the Eastern Cape. It was here that he became a cattle and sheep farmer as well as a merchant and washer. His merchandising firm was known as “Shumann & Co” and dealt mainly with wool from the Orange Free State. The origin of the name of his farm is very interesting. He set up a wool washing plant as a means of getting the wool into a fit condition for export. This led him to name his farm “Wasche-Erdwall”. The German words “Wasche” meaning to wash and “Erdwall” meaning a bank, referring to the wool washing plant on the river bank. Today his farm, the river and the surrounding area are known by the name “Waschbank”, the word “Wasche” has been retained, however the letter “e” has been dropped and “Erdwall” replaced by its English translation “bank”.

Wilhelm encouraged German investment in Cape Wool and, as mentioned, it was through him that the Hamburg brokers “Lippert and Co” built up a lucrative connection as wool importers. As a pioneer he developed new techniques when it came to sheep and wool farming. He was also an authority with recognised expertise, teaching farmers how to tend and shear their flocks. In 1863, Wilhelm together with a group of farmers and businessmen launched a joint stock company in Queenstown to import pure bred Merino stock from Germany. The imported rams and ewes were sold to Eastern Cape farmers, significantly improving local flocks.

With a courageous spirit, Baron Wilhelm Karl von Schumann played a major role in the development of agriculture in South Africa.

Baron Wilhelm Karl von Schumann (Portrait – Monochrome Style – 1865)

“Head of A Merino Ram” - This sketch is reputed to have been brought from Germany to South Africa by Wilhelm Schumann.

Wilhelm Schumann’s official Coat of Arms. It appeared on all correspondence related to “Schumann & Co”, his wool merchandising firm.

An advert from the “Free Press”, Queenstown’s first newspaper

Magdalene Morse-Jones is an Historian and Genealogist.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.