Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 2012, my wife Lorraine travelled on two weeks’ business to Lucknow, India, and I was fortunate to tag along for part thereof. Departing Lucknow by overnight train to Agra, we visited, amongst others, the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort, and the historic Roman Catholic cemetery. Too soon we departed for a rather tiring drive to New Delhi, relieved only by a stop at the Fatehpur Sikri, briefly capital of the Mughal Empire during the late 16th century.

In New Delhi, we walked along the ceremonial boulevard, previously called the King’s Way, but now the Rajpath, from the All-India War Memorial Arch to the summit of Raisina Hill. Ascending the slightly elevated Raisina Hill we passed between the two Secretariat Buildings flanking the inclined way, to end our meander at the imposing Rashtrapati Bhavan, official residence of the Indian President (see main photo).

Herbert Baker designed the elegant Secretariats and Edwin Lutyens the Rashtrapati Bhavan (Presidential Palace), for many years the largest residence of any Head of State in the world.

For this article, the terms used when this boulevard and buildings were designed during the period of the British Empire, namely King’s Way and Viceroy’s House, will apply.

Lutyens had visualised that the portico of the great Viceroy’s House, should be continuously visible from the King’s Way over the crest of the inclined way between the two Secretariat Buildings. When he realised that one loses sight of part of this great house as one approaches it along the King’s Way, he blamed Baker for devising a too steep and narrow gradient for the short, inclined way to the summit of Raisina Hill. Lutyens was so enraged by what he considered Baker’s duplicity on this matter that he accused him of spoiling his greatest work and bitterly referred to it as his ‘Bakerloo’. Their previous close friendship never recovered from this blow. This was to be my opportunity to finally see and experience first-hand what this quarrel between these two eminent architects was all about.

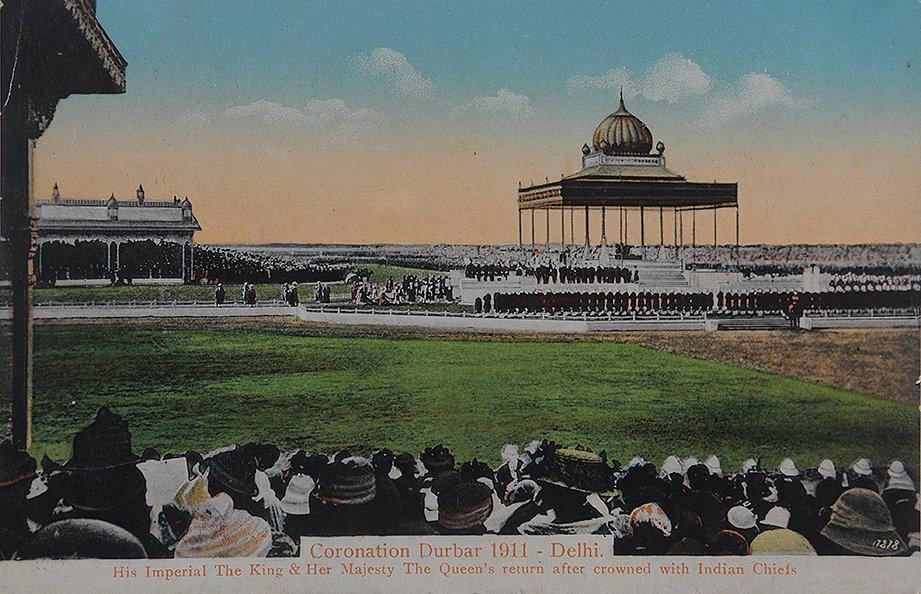

In December 1911, at the coronation durbar on the flood plains north of Delhi, the King-Emperor George V made a momentous proclamation: transferring the capital of India from Calcutta to the ancient Capital of Delhi. After relegated for more than a half a century to provincial status, Delhi suddenly was raised to the status of the capital of a subcontinent.

Old postcard of the Delhi Durbar

Perhaps, Delhi was selected because of its central location, ease of access, historic prestige and harsh though healthy climate, but most likely because of political necessity. The newly appointed Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, determined to restore the cohesion of all classes and races in India, viewed the restoration of Delhi to capital status as a much needed and unifying symbol.

Almost immediately planning for the new capital began. Sir Guy Fleetwood Wilson, one of the senior members of the Viceroy’s Council enthusiastically wrote: ‘I feel very strongly that this is an opportunity which has never yet occurred, and which will probably never recur, for laying the foundations of one of the finest cities in the world, and certainly the finest in the East.’

Appointing the three principal members to the important Delhi Town Planning Commission became a priority. After some debate regarding the suitability of British officials in India, it was agreed to appoint the three members with the required expertise from selected candidates in the UK. The first two: Captain G. S. C. Swinton, Chairman-elect of the London County Council and John A. Brodie, City Engineer of Liverpool were quickly appointed. Selecting a suitable candidate combining knowledge of architecture and town planning proved more difficult, but gradually two candidates emerged: Henry Vaughan Lanchester (1863-1953) and Edwin Landseer Lutyens (1869-1944). Nevertheless, there were some concerns about both. Lanchester, capable but apparently brusque and irritable, whereas Lutyens was considered too much of an expensive house architect. Secretary of State for India, Lord Crewe’s preference for Lutyens soon settled the matter. Elatedly Lutyens wrote to Baker announcing, ‘Delhi is alright!! I start on 27th March!!! It is a wonderful chance.’

The King received the three planning commissioners at Buckingham Palace on 21 March 1912. Holding forth for forty-five minutes, he instructed them that the Ridge to the north of the city, hallowed by its memories of the bloody recapture of Delhi during the Indian Mutiny, were not to be built on.

Old photo of the 1857 Mutiny Monument, North Ridge Delhi (Wikipedia)

Finding suitable and available land comprising sixteen square kilometres on which to erect the new city, to be named New Delhi to differentiate it from Old Delhi, and additional twenty-four square kilometres for the nearby Military Cantonment, proved time consuming and arduous.

The Commission arrived in Delhi in the middle of April 1912, where they were joined by their staff headed by Geoffrey de Montmorency as secretary and technical advisor. Lieutenant Chase in charge of maps, soon gained Lutyens’ respect and admiration for the speed in which he completed the necessary maps of areas inadequately surveyed. The Commissioners spent the remainder of April, travelling by car, or on elephant back, examining various sites, from surrounding suburbs scattered around Delhi, to jungle across the nearby Jumna (Yamuna) River and the arid hills intermingled with ruins to the south and west of the city.

The royal injunction to refrain from building on the hallowed ridge north of the city rather limited their options. Initially attracted to the north of the city but since much of the land there was already occupied, such estates as were available would have been constricted, leaving no space for expansion, as well as expensive.

Eventually the Commission concluded the slopes and plain between the Jumna River and the ridge to the city’s south-west, used for centuries as brickfields were best suited. Furthermore, not occupied by business or manufacturing concerns, the land could be acquired relatively cheaply. Here a level site was found that offered almost unlimited space for expansion yet was sufficiently near to Delhi to enable the positioning of ceremonial and connecting boulevards.

On 5 May 1912, Lutyens felt able to write home ’I have made up my mind as regards site, but not yet how to treat it’. Lutyens had seemingly already envisaged that Government House, subsequently called Viceroy’s House, and now Rashtrapati Bhavan (Presidential Palace), would resemble a British Palladian country house on a colossal scale, preceded by a majestic forecourt flanked by the Secretariat Buildings, at the apex of a grand processional axis.

Sketch of the original scheme 1912 for Government House and Secretariats on a level site (The Life of Sir Edwin Lutyens)

Lutyens was keen to co-opt his old friend and fellow architect Herbert Baker, to assist with the New Delhi project.

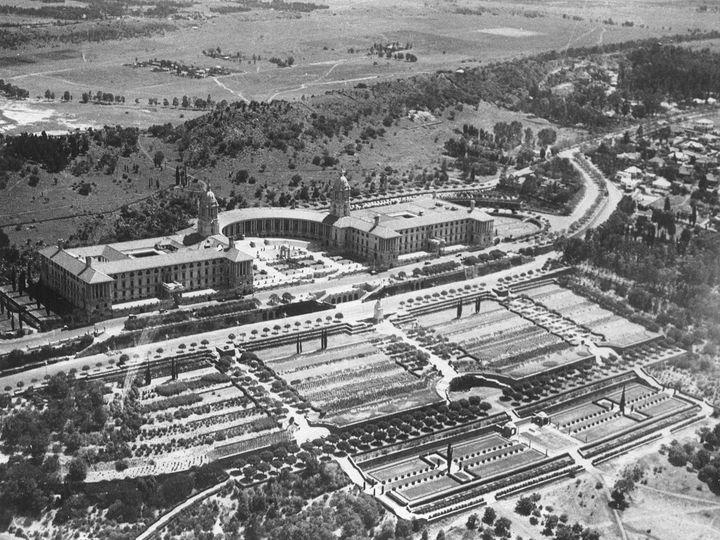

In South Africa, British architect Herbert Baker (1862-1946) enjoys a distinguished reputation. Here buildings are often attributed to him, even when in fact they are not. Perhaps, it is because Baker was the only British architect to have been involved with the designing of magnificent British Empire edifices on two separate continents. One is of course the Union Buildings on Meintjieskop, Pretoria, the first of a series of three great Imperial administrative and legislative buildings erected in Pretoria, Canberra, and Delhi.

Union Buildings from above (source unknown)

Doreen Greig, a South African biographer of Baker effused about the Union Buildings: ‘His modelling of the buildings on the steep slope of the koppie provide a rare architectural progression of flights of steps, gardens, and terraces connecting the different levels.’

But while the Union Buildings, are quite rightly considered Baker’s greatest work and a prominent landmark in this country, his substantial contribution to the monumental edifices of Imperial New Delhi and subsequent row with Lutyens are now largely forgotten.

In his Architecture and Personalities, Baker recalled how in the autumn of 1912, just as the Union Buildings were nearing completion, he had hints that he might be asked to accompany Lutyens as joint architect for the new Indian Capital. According to Baker, reports of his Union Buildings had suitably impressed Lord Hardinge, who wisely decided Lutyens needed a collaborator experienced in designing imposing government edifices.

Union Buildings on Meintjieskop (Herbert Baker Watercolour)

Without further ado, Baker penned an article for The Times, describing the appropriate style of architecture that would not only satisfy Indian sentiment but also embody the higher ideals of British rule in India. Arguing that there should be no direct imitation of Indian styles of building nor anything of the orthodox classical period, he advocated building according to the great elemental qualities of Grecian and Roman Mediterranean architecture with structural features of Indian architecture, symbols, myths, and history, grafted thereon.

Visiting Italy to refresh his memory ‘at the home of the Mother of Arts’, Baker was delighted to receive a telegram from the India Office inviting him to collaborate with Lutyens in Delhi.

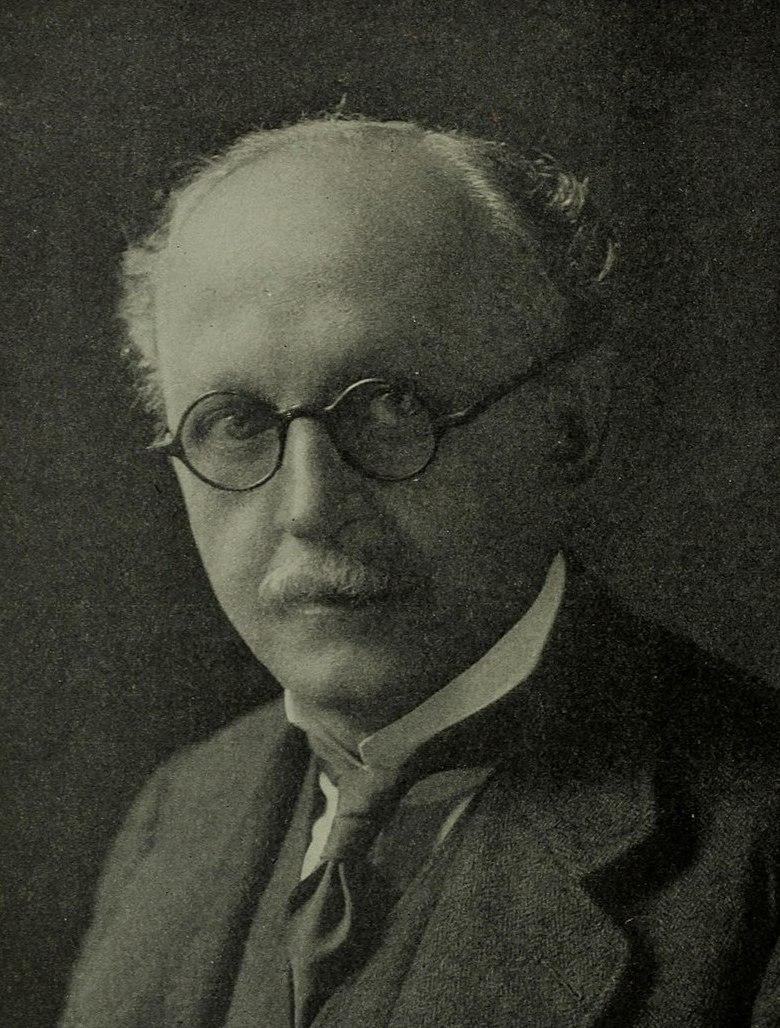

Baker had already completed his architectural apprentice pupilage with his uncle Arthur Baker and was Leading Assistant with the Mayfair based partnership of Ernest George and (Harold) Peto, when the eighteen-year-old Edwin Landseer Lutyens joined them in late 1887, after a brief spell at the Royal College in Kensington. Baker described meeting Lutyens there, ‘who, though joking through his short pupilage quickly absorbed all that was best worth learning: he puzzled us at first, but we soon found he seemed to know by intuition some great truths of our art, which were not to be learnt there’. The two became good friends. Lutyens saw Baker as one of the ‘big men – tall, manly, athletic, outwardly calm’, while Baker clearly recognised the younger man’s architectural genius.

Together, they attended fortnightly meetings of the Art Workers’ Guild at Barnard’s Inn Hall in Holborn, the architectural centre for the artist-craftsmen of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

During a walking tour through Shropshire and Wales in the autumn of 1888, they visited Stokesay Castle and its great but simple carpentry in half-timber and cruck-construction (curved timber used as roof support) made a great impression on both. Baker, drawing furniture, the 1637 roof of a tiny church at Rug near Llangollen and a tomb in the churchyard at Llancyl, noted Lutyens never sketched but after a quick glance relied on a retentive memory. Many years later Baker recalled how Lutyens told him all his timber work, which incidentally was always good, was based on what he observed on their meander.

Lutyens did not remain long with George and Peto, leaving after about six months, irritated by the limitations of an apprentice pupilage and a notion of having learnt little worthwhile.

Sir Edwin Lutyens (Wikipedia)

Barely 20 years old, Lutyens was commissioned to design the small country house Crooksbury near Farnham and before long he had a small but successful practice building cottages and lodges in Surrey.

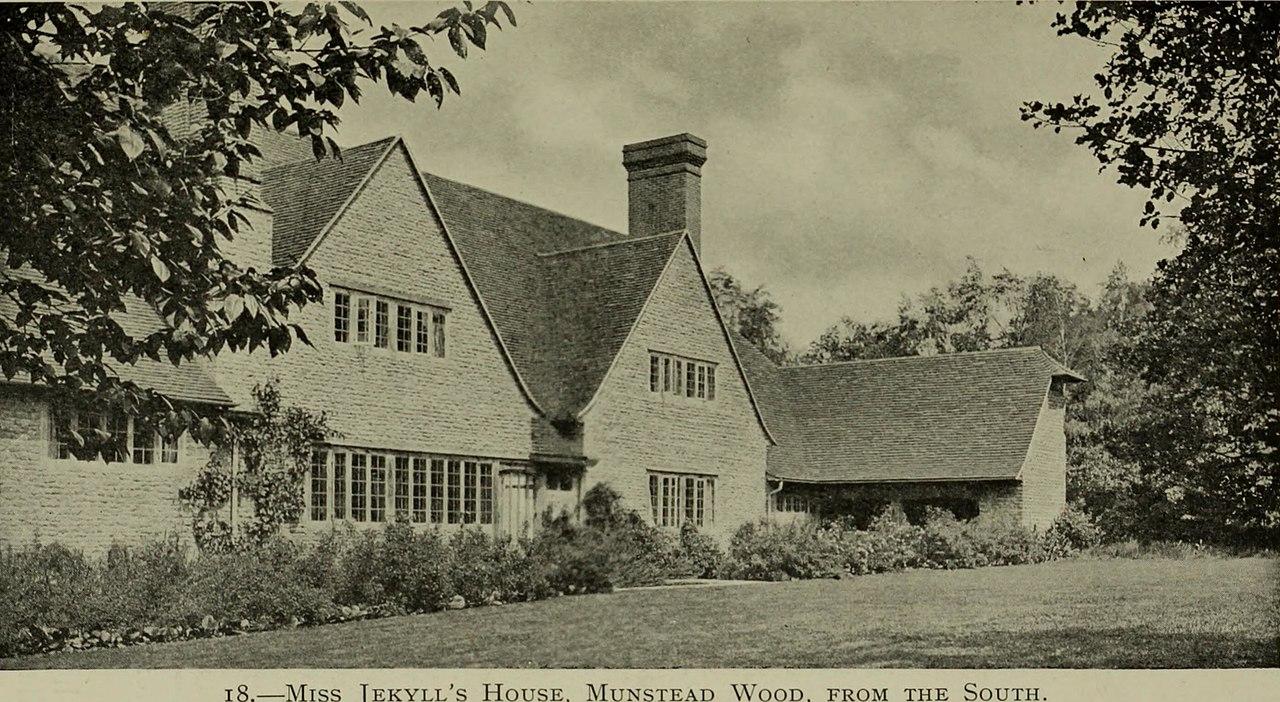

In 1890 he met Gertrude Jekyll, perhaps the greatest artist in horticulture and garden-planting that England has produced. Recognising a kindred talent, she entrusted Lutyens to design her long cherished dream house, Munstead Wood in Surrey.

Munstead Wood (Lutyens Houses and Gardens via Wikipedia)

The lovely house he designed for her so perfectly complemented the existing Jekyll garden that she thereafter used every opportunity to promote his talents. Lutyens took Baker along to meet her and they too became friends. Through her, Lutyens and Baker both learnt how to enhance their buildings with appropriate plants, trees, and gardens; knowledge that would prove essential in both South Africa and New Delhi.

Shortly after Lutyens left George and Peto, Baker too left to start his own small office in Gravesend, not far from Cobham, where he was born. He restored some timber houses in the area and completed various perspectives for Lutyens as well as assisting him with supervising some of his projects. But finding architectural assignments scarce, Baker sailed for Cape Town in search of better opportunities. Here he was thrilled to discover the dignity and beauty of the old Cape Dutch houses, though at the time little appreciated by the colonists themselves. His meeting with and subsequent work for Cecil John Rhodes, paved the way for many other fine commissions during his subsequent 20 years stay in South Africa, but that is another story.

A view of Groote Schuur in 1988 (Janek Szymanowski via Wikipedia)

Stonehouse, Baker's home in Parktown (The Heritage Portal)

During the late summer and autumn of 1912, the three members of the New Delhi Planning Commission worked in London while their preliminary proposals were examined on the spot by Indian government officials. The southern site was approved in principle, but local government officials soon developed second thoughts about the proposed site of the Viceroy’s House. They objected that it was sited way too low for such a prominent building serving the jewel in the British Crown.

Lord Hardinge quite concurred. Writing to Swinton he requested the whole matter of the siting of Viceroy’s House to be reconsidered, adding the site on top of Raisina Hill with views over Delhi presented great attractions. It would imitate Versailles and its gardens and appeal to the Indians who from miles away could point to it as the residence of the Viceroy. Furthermore, having the Viceroy’s House on Raisina Hill and facing the Jumna River rather than northeast to Old Delhi, would avoid any comparison to previous collapsed empires.

In the meantime, Baker wrote to Lutyens outlining their proposed respective responsibilities: For Lutyens the Great Place and Viceroy’s House; and for Baker the two Secretariat Buildings and the Parliamentary House.

Just as the Commission started making progress a serious incident in December 1912 threatened to delay matters. A bomb thrown at close range at the Viceroy and Vicereine’s State elephant, exploded in the howdah, killed the mahout, and seriously injured Lord Hardinge.

Unsettled by the political motives for his near assassination, Hardinge requested the Committee to reconsider the Ridge north of Delhi. Fortunately for Lutyens he had gained a useful ally in Lord Montagu who assured him that he had impressed upon Hardinge the necessity of providing sufficient space for moving all Government departments to Delhi, instead of keeping some at Calcutta (Kolkata) and others at Simla (now Shimla and at that time the Summer Capital during the hot Indian summer).

When Baker stepped ashore at Calcutta in February 1913, Lutyens was on hand to greet him in person.

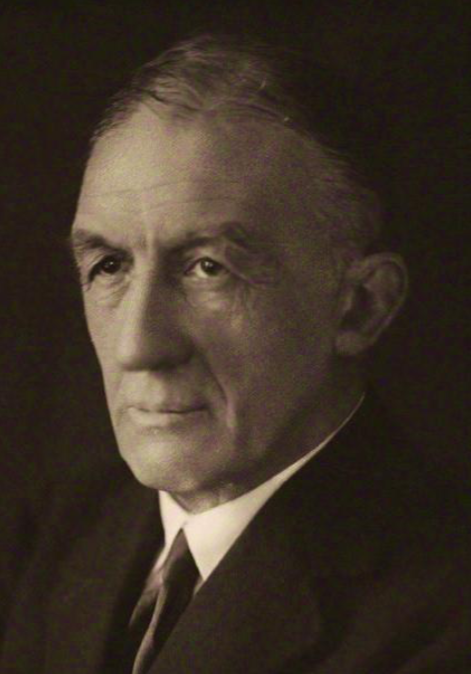

Herbert Baker in later life

They had not seen one another other since 1911 in Johannesburg, when Lutyens was commissioned to design the Rand Regiments Memorial and the Johannesburg Art Gallery, and the greetings were mutually warm and friendly. Lutyens wrote home, ‘it is great fun and comfort having him’. But by middle February some doubts were surfacing, ‘I don’t think he treats architecture as seriously as I do, he makes her the handmaid of sentiment’.

Rand Regiments Memorial (Kathy Munro)

Johannesburg Art Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

Baker, fresh from his completion of the celebrated Union Buildings on Meintjieskop, advocated the construction of the Secretariat Buildings on the same elevation as the Viceroy’s House on Raisina Hill. His argument that the buildings containing the actual machinery of government should be at the same elevation as the building symbolising the crown, made a lot of sense. On the summit, the administrative and executive powers would together form one composition expressing unity in the instrument of Government.

Lutyens on the other hand, concerned this would detrimentally affect the visibility of the Viceroy's House from certain points along the King's Way, and that additional costs would be incurred by levelling the extended area, demurred, but for the moment serious disagreement was avoided.

In a joint letter to the Viceroys, the two architects agreed the Secretariats and Viceroy’s House should be erected on the summit of Raisina Hill with an inclined way giving access to both edifices. The Viceroy’s House would be some 250 meters to the rear of the two Secretariats.

View of the controversial inclined way between the flanking Secretariats to Viceroy’s House beyond.

Both architects confirmed in writing the gradient of the inclined way bisecting the two Secretariats and terminating at Viceroy’s House would slope at a maximum of 22.5.

Lutyens initially failed to realise that such a steep and narrow gradient would hide the lower portion of the Viceroy’s House from sight as one approached the inclined way, and in turn Baker probably assumed that Lutyens accepted this as an inevitable consequence of the Secretariats being erected at the same level as this house.

It was only in January 1915, during construction of the inclined way ascending Raisina Hill, that Lutyens realised with shock and dismay the effect the gradient would have on the visibility of Viceroy’s House. Appealing to both the Imperial Delhi Committee and the Viceroy to have the gradient reduced and widened, Lutyens was devastated when neither was prepared to do so, because of increased costs and the problem of securing easy access between the two Secretariat buildings. The Viceroy also responded that he always envisioned having Viceroy’s House in solitary majesty on the summit of Raisina Hill with the Secretariats on lower ground. When the architects proposed to place both Viceroy’s House and the Secretariats on the hill summit, he accepted their proposal as having inherent merit. Perhaps, Hardinge also harboured some schadenfreude. The architects having proposed and agreed to share the summit would now have to live with the consequence of their decision.

Both architects left Delhi shortly afterwards, continuing to argue fruitlessly on the return journey to the UK.

Old photo of the Viceroy’s House (Wikipedia)

Back in London the dispute on the gradient of the inclined way continued unabated and both Lutyens and Baker detailed their respective arguments to the Imperial Delhi Committee and Lord Hardinge. Although Lutyens attempted for further six years to have the gradient of the inclined way reduced, his attempts were to no avail. The gradient of the inclined way still today remains at 22.5.

Approach from the east hiding the Viceroy's House (Wikipedia)

Nowadays few people know or even care that the Viceroy’s House partially disappears as one ascends Raisina Hill. But at the time and for years later, Lutyens ensured everyone realised who was responsible for what he described as spoiling his life’s greatest work. Having designed many imposing houses in the UK, the British embassy in Washington, as Principal Architect for the Imperial War Graves Commission responsible for the poignant Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, and of course the hallowed London Cenotaph to the 1914-18 dead, Lutyens had all the important societal connections that even a distinguished colonial architect such as Baker, failed to match. Of course, Lutyens’ marriage to a daughter of a former Viceroy of India did no harm to his standing either.

In the January 1931 magisterial edition of Architectural Review, Lutyens received all the praise while Baker’s features of the Indian Parliament building were bitingly dismissed, with: ‘In between the pillars of the Parliament building, are hung fretted stone panels as though fixed by clothes pegs on a line. Here are not only pants, but petticoats, camisoles, night-dresses, and even tea gowns.’

North Block Secretariat (Wikipedia)

Lutyens’ son Robert continued the sniping at Baker. In his booklet Sir Edwin Lutyens: An Appreciation in Perspective by His Son, Baker is mentioned only once, after the author’s rather pretentious description of Viceroy’s House as the greatest single masterpiece of European architecture. He then disdainfully exclaimed, ‘No, after Viceroy’s House, Baker’s banalities are almost a relief. One is so accustomed to live surrounded by the commonplace that the sight of the Secretariats makes one feel comfortable again!’

In contrast, Baker maintained a dignified silence. In his Architecture and Personalities published in 1944, the year of Lutyens’ death, he commented that the differences of opinion between himself and Lutyens had their roots in their different natures and outlook on art. Baker maintained that Lutyens’ intuition and talents in design equalled those of Christopher Wren. According to Baker, Lutyens concentrated his extraordinary powers and his immense industry and enthusiasm on the abstract and geometrical qualities to the disregard of human and national sentiment and its expression in his art. While acknowledging his own inferiority in these talents of the intellect; Baker argued that content in art, national and human sentiment, and their expression in architecture were to him of the greatest importance.

For both architects New Delhi turned out to be a watershed event. Lutyens was widely praised for his design of the magnificent and imposing Viceroy’s House and he continued to turn out master pieces right up to the outbreak of the Second World War.

In contrast, the criticism and sneers destroyed Baker’s confidence to a considerable extent. Roderick Gradidge, the late British architect, author on architecture and fan of the Arts and Crafts movement, unhesitatingly states that none of Baker’s post Delhi buildings meet his previously high standards. Not only that but he also accuses Baker of ruining Soane’s renowned Bank of England building with his poorly considered renovations'.

Perhaps, Baker’s mistake was to fly too close to the architectural sun, personified by Lutyens, not realising he would be scorched. But be that as it may, in South Africa, Baker’s reputation remains untarnished.

Herbert Baker bust at Northwards (The Heritage Portal)

Northwards (The Heritage Portal)

But, as a once famous and later vilified British General once said, ‘In fifty years it won’t matter’. Today, people of India are inordinately proud of their magnificent New Delhi Government edifices, and the monumental row of almost a century ago is almost forgotten.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Baker H. Architecture & Personalities. Hazell, Watson & Viney Ltd. 1944.

- Greg D. E. A Guide to Architecture in South Africa. Howard Timmins. 1971.

- Greig D. E. Herbert Baker in South Africa. Purnell. 1970.

- Hopkins A. & Stamp G. (Editors). Lutyens Abroad. The British School at Rome. 2002.

- Hussey C. The Life of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Country Life. 1950.

- Irving R. G. Indian Summer. Lutyens, Baker and Imperial Delhi. Yale University press. 1984.

- Keath M. Herbert Baker. Architecture and Idealism 1892 – 1913. The South African Years. Ashanti Publishing. Not dated.

- Lutyens R. Sir Edwin Lutyens: An Appreciation in Perspective by His Son. Country Life Ltd. 1942.

- Read W. Keeping the Jewel in the Crown. The British Betrayal of India. Birlinn Ltd. 2016.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.