Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In May 2018 Robyn Keet, our picture library manager at the time, teamed up with the PhotoZA Gallery in Rosebank Mall, Johannesburg, to create an exhibition of photography that covered the apartheid period in South Africa from the 1950s to the 1980s. DocuFest Africa: The Exhibition, showcased at times rare and unusual images of life in South Africa taken by leading photographers at the height of apartheid. Curated by Reney Warrington, the Exhibition was drawn from collections represented by Africa Media Online. It covered a broad cross-section of society at the time, from the woman’s movement and boys on the border to protest action, the trade union movement and the development of Johannesburg.

The collection of images was at one time unfamiliar – speaking to us from a different time, a different political reality – and familiar, with so many of the challenges faced then being still with us in 2018. The exhibition included images from the Tiso Blackstar group Collection, Paul Weinberg, Gille De Vlieg, George Hallet, Eric Miller, Graeme Williams and a single image by me, David Larsen.

On Saturday, May 12, 2018 veteran Black Sash activist and photographer, Gille De Vlieg, conducted a walkabout of the DocuFest Africa exhibition, particularly her images. The walkabout gathered a small crowd including a number of Black Sash members who were able to share their experience of protest action under apartheid.

Our opening night was the same night that David Goldblatt was opening the “Five Photographers: A tribute to David Goldblatt” exhibition at the French Institute. The crowd seemed to move between to the two events. The contrast between the exhibitions fascinated me. Reney worked hard to present a different take of the apartheid era. There were no scenes of violent clashes or police brutality, rather images of new buildings in Johannesburg and scenes of everyday life were interspersed with images of protest. And she seemed to pay particular attention to images of protest by white South Africans. We were looking around the exhibition and my colleague, Bandile Sizani who is a young adult, commented that he had not been aware that so many white South Africans had protested against apartheid. It was a sentiment I heard more than once from young people attending the exhibition. Reney did well to present a view of the normal and the abnormal existing side by side. Yet when all is said and done, there was one big story in that era, the background against which the normal took place, and that was the absurdity and dysfunction of apartheid. At the end of the day, photographers of that era had a cause and the cause was clear.

That is not the case in post-apartheid South Africa. Whatever you think about the rate of progress since 1994, politically before and after the end of apartheid is like chalk and cheese. As I said in my opening address of the exhibition, though much looks the same, the huge change is that in that era the law was against what was right and in our day, on the whole, the law is with what is right. That is a sea change. But not having a massive common societal enemy makes for complexity. And that complexity is reflected now in what photographers choose to turn their lenses toward. After apartheid, for some years, many South African photographers found themselves at sea. The big story, the great cause was gone. It wasn’t just photographers who felt this. I remember post-1994 going along to a protest outside the President’s house in Newlands, Cape Town. I was marching along with two women who were part of the SADTU teachers union. We got chatting. Disappointed with the protest, one of the teachers said to me something along the lines of “… this is not like those days. In those days our fight was clear and we were on the side of what was right. Now it is more difficult to know.” And so it has been with photography. Documentary photography moved from the era of the collective voice against a common enemy, to individual voices highlighting diverse issues. This, for me, was reflected so clearly in the contrast between “DocuFest Africa: The Exhibition” and “Five Photographers”.

Black Sash activist and photographer, Gille De Vlieg converses with a fellow Black Sash member during the DocuFest Africa exhibition walkabout. Behind are images from the Tiso Blackstar (formerly Times Media) Collection.

The DocuFest Africa exhibition at the end of the day was about one dominant thing, the injustice and preposterous nature of apartheid that even moved comfortable middle-class white South Africans to take to the street in protest. The Five Photographers presents four completely different visions with no discernable common backdrop besides, perhaps, the human condition. Alexia Webster turns her lens on portraits with passers-by using street studios in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Mexico, India, refugee camps in DRC and South Sudan, and rock quarries in Madagascar. Jabulani Dhlamini provides a post-apartheid reflection on the starkness of Sharpeville, the site of an apartheid protest and massacre. Mauro Vombe focuses the daily cycle of survival photographing the press of people on public transport in Mozambique. And Pierre Crocquet explored pedophilia, both victims and perpetrators in his chilling “Pinky Promise” exhibition and book. The common backdrop to every story is no longer clear. Each photographer in the post-apartheid era has had to work hard to develop their own voice, their own cause or reflection of the world in which they live. In this sense, South African documentary photography has needed to return to what David Goldblatt argued for at the Culture and Resistance conference in Botswana in July 1982 – the integrity of individual artistic voice. In this sense, we have been forced to re-enter the mainstream of documentary photography around the world.

“Pinky Promise” the haunting work of deceased South African photographer Pierre Crocquet that focuses on child sexual abuse. As David Goldblatt said when curating his work: “Pierre Crocquet tried to interest me in his work at a time when I was heavily committed to a major project. To my shame I failed to respond and when I finally tried to do so, he was dead. There can be few who engaged with paedophilia and child abuse so plainly, frankly and yet delicately as Crocquet. Seldom has any piece of work in photography and words been more frighteningly titled than Pinky Promise. Survival in “Pinky Promise” is in utter contrast to survival in Mauro Vombe’s buses.”

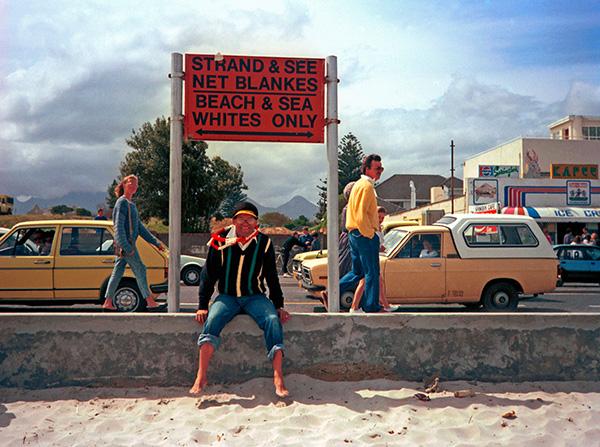

Main image: Alan Boesak at a beach demonstration in 1989. The image was included in the Exhibition by Reney without her knowing, so I am told, that it was mine. It was my first year as a student at the University of Cape Town and I don’t believe I even owned a camera. I am likely to have borrowed my brother’s camera for the day. A group of us from UCT went to join the beach protest in Strand. It was August 1989 and beach protests had been organised on the “whites only” beaches of Strand and Bloubergstrand. About 300 of us made it through to the Strand before a heavy police presence prevented any more protesters from reaching the beach. The police also prevented the press from getting there. I seemed to be the only one with a camera on the beach that day. Allan Boesak was there and he sat down under a sign that said “Strand & See Net Blankes – Beach & Sea Whites Only”. I took two shots of him alone beneath the sign before people piled in to be in the picture.

This article originally appeared on the Africa Media Online website on 24 August 2018.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.