In October 2016 Johannesburg celebrates its 130th birthday. From those early beginnings as a mining camp on the veld here is a city in its second century sufficiently mature to realize that there are some buildings worth celebrating and preserving; the camp grew to a town, then a city and is now a sprawling metropolis. It was a city with little appreciation of its past and property developers then and now seldom show respect for the old and out of date. Johannesburg is a young city and while it knows its roots, various waves of immigrant taste and prevailing international styles have shaped and continue to shape its built environment.

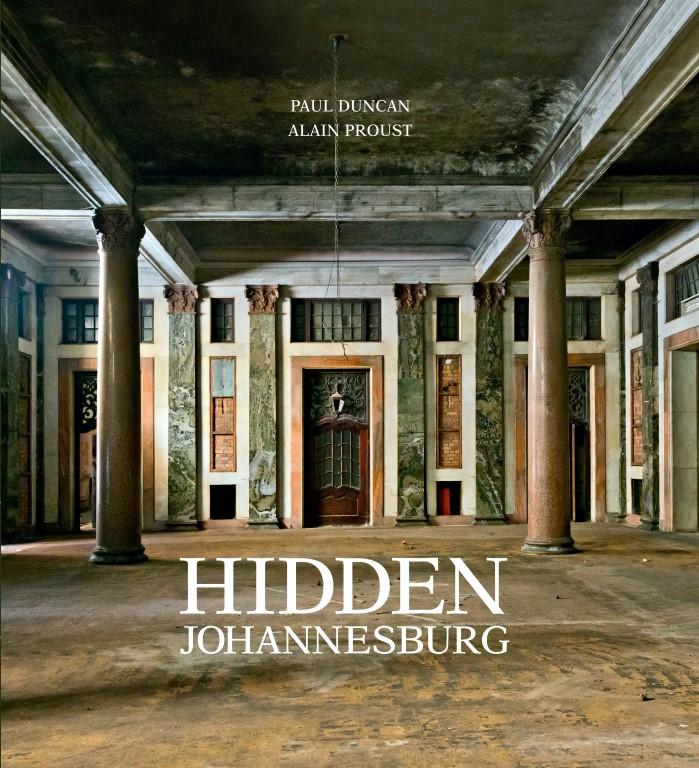

The city we see today reflects cycles of construction and demolition, gold mining prosperity and economic decline. It is a miracle that enough of the past survives, often serendipitously, to make it a European cum African metropolis blending old and new. So much of the city’s architecture is visibly “colonial”. One can find architectural gems that could easily be absorbed into English town landscapes or other newly founded Victorian cities, for example Melbourne Australia or Christchurch New Zealand. The language of architecture is also international and the architects of South Africa were either trained abroad, travelled to draw inspiration from new movements, old traditions or fashionable styles or consciously looked for international models. But one also has to look for the beginnings of vernacular architecture and how local materials (for example the quartzite rocks that came with the geological bonanza) inspired new shapes and designs and how the traditional Cape Dutch styles were replicated on the Highveld. Some of our architecture is extraordinarily and self-consciously modern and brings New York to Johannesburg. Duncan in his text and Proust in his photographs set one thinking about architectural origins, the essential character of our buildings, the use of a different building materials, whether “form followed function” and what comprises an architectural legacy.

The city we see today reflects cycles of construction and demolition (The Heritage Portal)

If you love Johannesburg and its rich diversity of architecture and its moods generated by Highveld sun, this book will appeal on looks alone. It is a beautifully produced book and I cannot think of many other books on Johannesburg that compare from a photographic perspective. With the selection of 26 favourite buildings* or places drawn from the established parts of the city, it offers a wonderful mosaic of what makes Johannesburg a remarkable place.

This book is a superb birthday present to the citizens of Johannesburg who are interested in heritage, city buildings and architecture. The book is a visual treat and a sensual delight for the armchair city walker, primarily because many of the photographs are of the interiors of unusual places. The exterior photos were shot on sunny days and are infused with that bright Highveld light and good photographic moments. There are no people in a single photo, so the changing demography of the city is missed and in a sense there is a certain timelessness about the images. All the photographs are current but there is the feel that the photographer could have been at work 40 or 50 years ago.

This volume by seasoned publisher and journalist Paul Duncan and talented professional top photographer, Alain Proust, opens the doors to reveal the “hidden” interiors of well-chosen buildings in Johannesburg. The strength of the book lies in the eye of the photographer as he captures a stained glass church window, a sculpture, a staircase, the intimacy of a domestic space, imposing vestibules, the detail of a façade, or artistic ceramic tiles. It is his lens and eye that interprets the old city. Every photograph is a quality colour illustration that makes one linger long on this armchair journey through their and our city. It is a coffee table book, rather than a guide book as you need a comfortable chair, a book support and a glass of wine to turn the magical pages of photographs. The book is a visual delight and when you are out and about armed with a camera on a Photowalkers trail you will doubtlessly be inspired to look for photographic angles used here.

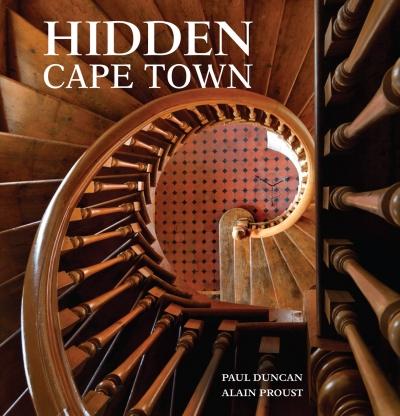

Proust’s work on Cape Town is well known. There is a companion volume to the Johannesburg book, “Hidden Cape Town”, equally stylish and appealing.

Hidden Cape Town book cover

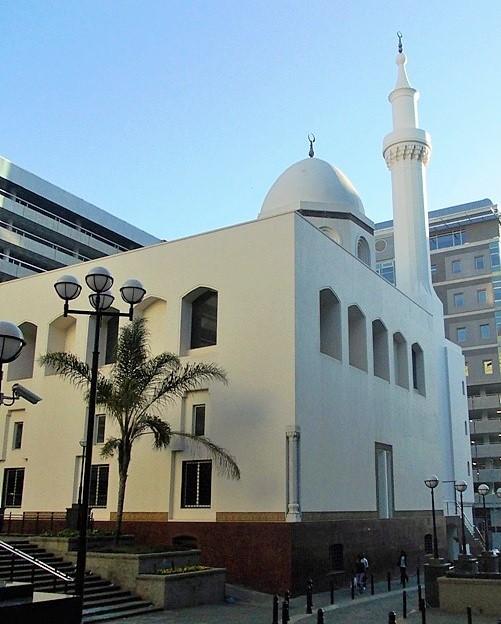

In the Johannesburg book, the authors also raise the possibility that some fairly recent special places should be added to the list of city treasures because of their history or associations. Their definition of Johannesburg is broad, as Midrand is represented in the new but traditional, Turkish inspired, Nizamiye Masjid and a whiff of the Witwatersrand is presented with the inclusion of the Baker designed church, of St Michael and All Angels in Boksburg. If you are looking for a classic Arts and Crafts fine stone work church, why not select St Aiden’s Anglican Church off Louis Botha Avenue in Yeoville? This is roughly the same date as the Boksburg church (1912), the architects were Waterson and Veale. If you are going to go to Boksburg why not Springs with its art deco heart? Or why not choose a central city mosque such as the Kerk Street Mosque?

Kerk Street Mosque (The Heritage Portal)

The Nelson Mandela House in Vilakazi Street in Soweto is on every tourist’s list due to the history and presence of its most famous occupant but the author misses the whole point about the economics and architecture of this little house. Why was this house here? What were the architectural merits? Is this one example of vernacular domestic architecture?

The section on the Old Fort does not limit itself to the fort and its Kruger Republic roots and spills over into the prison sections located lower down the hill. This begs the question why the Women’s prison does not feature? That is a rare architectural peculiarity.

There are other oddities that jar. For example, the South African Railways advert marketing regular train journeys between Johannesburg and Cape Town positioned on the contents page is not a good choice. It has no date but probably circa 1936, the year of the Empire exhibition in Johannesburg when two million visitors went to Milner Park. This advert features a line drawing of a Cape Dutch homestead. For a book on Johannesburg this makes little sense when there are some marvellous Johannesburg jubilee postcards and photographs. Why include a stunning photo of dappled sunlight on the Chassidic synagogue in Yeoville (now no longer a shul) with the sculptural work of Edoardo Villa when this is not one of the featured treasures? Why introduce Hermann Kallenbach as an aesthete and boy-builder; yes he was Gandhi’s friend, but his architectural practice preceded that relationship and extended until his death in 1945. Why repeat the unproven, undocumented and now dismissed but titillating claim that Mrs Dale Lace’s son was the son of Edward VII? The John Moffat building at Wits (home of the School of Architecture and Planning) was named for the architect John Moffat because he bequeathed his fortune to Wits not because of his importance as an architect. Baker cannot be discussed without reference not only to Fleming but also to Sloper. Architectural partnerships mattered. If you want to know more about Johannesburg architects and architecture, then Hidden Johannesburg is just a taste of what you will find in the two Chipkin authoritative works or van der Waal’s From Mining Camp to Metropolis. There is no new original research here at all and the secondary sources used are by no means comprehensive. The author has relied on conversations and gloss. I abandoned reading the text because it irritated more than informed but I could not stop enjoying the wonderful photographs.

The cover photograph (see main image) is of the old Johannesburg Station and while every other building is in use as a church, a school, a museum, a bar, a corporate headquarters, a home, a provincial legislature, a club, this is the one space that is in a terrible state of dereliction. Is there a silent appeal here to Transnet to recognize the treasure in the Station and do something about the restoration of the Blue Room and the open courtyard which were once much beloved by Johannesburg people?

Park Station (Hidden Johannesburg)

The term “hidden” is puzzling. It is a useful word which has many synonyms ranging from concealed and unknown to secret and obscure. It is a word that gets around the problem of being limited to heritage buildings but I don’t think one can escape the heritage feel of the book. Perhaps “hidden” is about open access and gaining admission to places which are normally closed to the public and which have another function. However, the authors make no mention of the work of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation which offers weekend tours and visits with knowledgeable and enthusiastic Johannesburg aficionados to all these choice Johannesburg places. There is a concluding list of mainly website contact information to gain access, but I don’t think that the places are as “hidden” as the authors imply. I know touring the highlights of Johannesburg architectural gems can be a hard slog, but there are opportunities galore for those who enjoy knowing their city.

The interior spaces of The View in Parktown are featured (Hidden Johannesburg)

It is a very personal choice when it comes to deciding which buildings belong in a book which will sell to Johannesburg people and to tourists. It is a highly desirable volume for any Johannesburg collection. But there are some notable omissions. There is no discussion as to why this particular edifice was chosen ahead of another. No doubt there was a far longer list of buildings or “hidden” interiors that did not make the final editorial cut. Neither of the two Johannesburg universities feature (a number of spaces and places at Wits and UJ would have been at the top of my list). If you are looking for modern architectural landmarks that define the city, then surely either one of the two towers (Brixton and Hillbrow / originally named for Hertzog and Strydom) should be in the book). What was significant about say, the Carlton Centre and the Carlton Hotel or Ponte - these are Johannesburg's iconic landscape high rises. The Baker masterpiece, the S A Institute for Medical Research has been missed as has the Lutyens Johannesburg Art Gallery. You can quickly develop a list of your favourite Johannesburg buildings and work out which have been omitted or included.

S A Institute of Medical Research (The Heritage Portal)

There is no index and no footnotes of sources. The bibliography reveals that the research put into the book has been rather limited. The strength of the volume lies in the visual appeal of the photographs. They are exquisitely beautiful and are a very special birthday gift and homage to Johannesburg.

2016 Guide Price: R390 (available online and at all good bookstores)

The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation has negotiated a special price of R320.00 with the publisher. To place your order email mail@joburgheritage.co.za. Once payment has been made the book can be picked up from the JHF offices at Northwards in Rockridge Road, Parktown.

Review copy kindly provided by Penguin Books

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.

* There are two further buildings included that are not in Johannesburg at all and while interesting don’t really “belong”