This is a collection of essays by 12 distinguished academics who are top art historians, visual culture analysts, historians and educational leaders. They have teamed up to analyse the phenomenon of Afrikaner nationalism as this political movement or ideology found expression in visual images, public sculptures, architecture, cartoons, and the Voortrekker Monument.

Voortrekker Monument (The Heritage Portal)

The ground covered is diverse and disparate in subject matter. It is the very diversity of subject matter that makes the book so appealing. The editors, Freschi, Schmahmann and Robbroeck have skilfully explained what these images are about and why indeed they are troubling in an introductory essay and then beyond as each of the editors contribute a chapter. The book is arranged around four themes: part one revolves around nationalism in fine art and architecture, part 2 focuses on two University campuses and what happens when past sculptured heroes are dislodged from their pedestals, part 3 explores ideas of nation and national identity as portrayed in photographs, and the final part 4 unpacks how popular mass media, cartoons, comics, films and magazines promoted then current political messages to identify a volksmoeder, send the white young school leaver to the border or give a fairly heavy handed portrayal of what Afrikaner nationalism meant in a Honibal cartoon in The Burger newspaper.

There was clearly a challenge in finding ways of relating 11 essays to fit into four themes. The structure underpinning the book is clever but with the exception of the introduction and the first essay by Albert Grundlingh these essays each stand alone and don’t interface or interfere with one another. There is no real chronological mapping of topics. Each essay provides grounds for thought and reflection. This is a book where you can start anywhere - tackle an essay and then return to the introductory essay to backtrack to the overview.

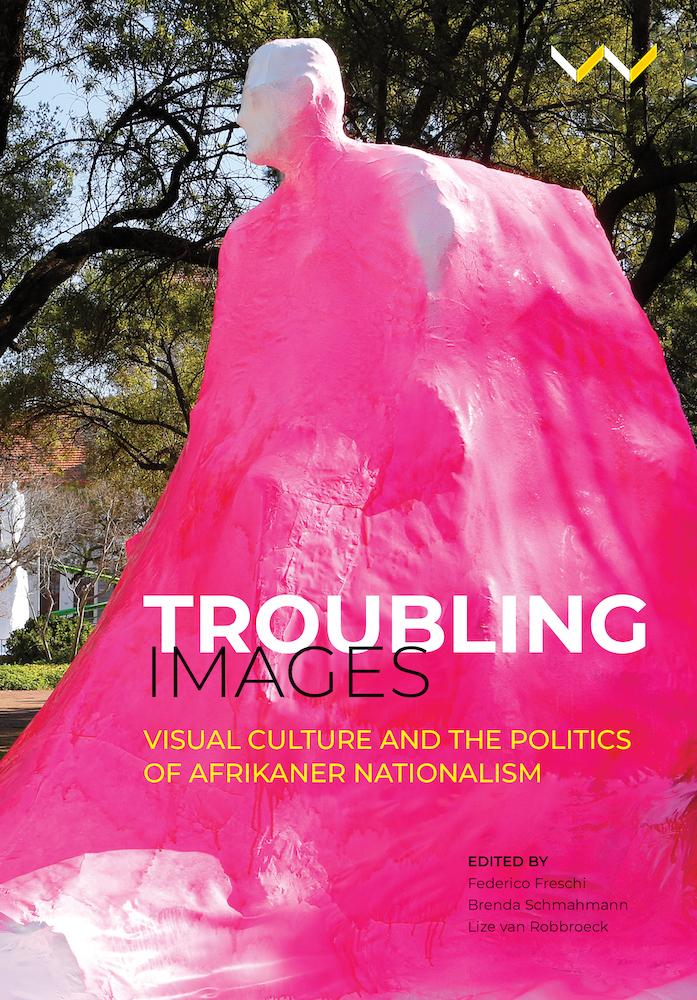

Book Cover

The introductory essay by the three editors attempts to place Afrikaner nationalism in an international context and asks the question why has there been a turn towards resurgent nationalism in the worlds of Trump, the British Brexit movement, the Indian Hindu-first movement of Modi. The authors quote Mzukusi Qobo who argues that nationalism thrives in conditions of social marginalisation but such a position evades and does not even get into the fraught area of African nationalism and how nationalism is used to bolster power once the pinnacle of political power has been reached. There are a great many curious questions around African nationalism, foregrounded by the ANC but also more extremely by the EFF. I found myself wondering why the theme is really a backward looking one and in that sense Afrikaner nationalism belongs to South Africa’s past. A book on African nationalism and its visual expression would be as interesting.

I thought that the essay by Jonathan Jansen was the one essay that engages with how different and evolving forms of nationalisms collide, conflict but might also accommodate one another. Jansen served as the Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Free State for seven years and had to address the future of statues such as the Free State President M T Steyn and C R Swart, where UFS is not Wits or UCT and where it still educates the Afrikaners of the Free State. His is a wise, experienced and tolerant perspective. Well worth a read.

The principal opening essay by the distinguished Afrikaans historian Albrecht Grundlingh provides a broad overview of the key factors that underpinned the emergence and evolution of Afrikaner nationalism. Why is it that English liberals are more interested in interpreting and understanding Afrikaner nationalism than the Afrikaners themselves? Grundlingh’s analysis of the link between poverty and the Afrikaner political routes out of poverty for an entire generation is fascinating. There is a hint that this is a complex subject that must explain so many variables and possibilities - Why did Afrikaans women who came to the cities and took up jobs in textile and clothing factories fight for trade union rights under the leadership of Solly Sachs? Overall it is a rich and competent historical overview though repeats some of the editors’ summary of what the book is about.

Lisa van Robbroeck tackles the Empire Exhibition, Johannesburg 1936, as a grand motif event of the thirties. She looks for the expression of Afrikaner nationalism in the Art exhibition. The cultural influence of Martin Du Toit, an Afrikaner ideologue in curating the South African input to this exhibition, is explored. There appears to have been a contest between including art regarded as progressive and modern whilst not neglecting the traditional and canonical. Young modernist had to be weighed against the older popular artists with established earlier 20th century reputations. There are some insights about comparisons with Canada and its emerging nationalism as expressed in its art (after all the Empire was on show). Lisa argues that modernist nationalism was subtly infused with sectarian Afrikaner interests with the Transvaal becoming much more prominent in is cultural influence. This means that the architecture and indeed the Cape influence in the government pavilion (still there at Wits) and meant to look like a Cape Town house, along with the recreation of the Paarl wine estate La Provence (again the Cape influence pushes to the fore) gets no mention in this overview of the Empire exhibition. Instead her focus switches to the historical pageant - a sort of entertainment organized around a Darwinian civilization march- past ending with the Great Trek and again the Afrikaner view of history in the portrayal of the Great Trek and the heroically portrayed Voortreker battles as conquest moved inland. My concern is that this chapter gives a very partial view of the Empire Exhibition and the multiplicity of motives and messages.

The essay on Architecture and Afrikaner Nationalism by Federico Freschi will appeal to the architects and adds to architectural history. I fear though that this essay will be lost to that discipline because it would have fitted better into a fuller architectural book. Freschi has some new insights on what Moerdijk was attempting to achieve in the Merensky Library and in the Reserve Bank building. Here the interesting question is whether these architectural works expressed modernism, Art Deco or ethnicity. The influence of Niemeyer and the Brazil Builds exhibition influenced not only Afrikaans or state commissioned architecture but in fact a whole generation of architects. I recently acquired a selection of books from the Monty Saks library and its so evident that many architects of that generation were influenced by “Brazil” and Walter Gropius. I found it very odd that Manfred Hermer and his Johannesburg Civic Theatre fits into a chapter on Afrikaner nationalism inspired architecture. Hermer had already established a reputation as a first rate architect of theatres (he was very much a theatre man) and one needs to look at Swedish and even Canadian influences. I don’t think that Freschi carries the case for Boere Brazil or Boere Brutalism. I can think of better examples even in sixties and seventies Johannesburg to show the power of Pretoria, for example in commissioning the College of Education (now the Education School of the University of the Witwatersrand) and the Johannesburg Hospital in Parktown (now the Charlotte Maxeke Hospital). The Freschi chapter is wide ranging but I am not sure whether architecture of the period 1936 to 1966 can be quite so readily yoked to Afrikaner Nationalist ideology.

Johannesburg Hospital, today Charlotte Maxeke (The Heritage Portal)

The chapter on David Goldblatt’s photography by Michael Godby and Liese van der Watt challenges the authenticity and honesty of Goldblatt in his photographic representations of Afrikaners and their identity. This essay is not so much about Afrikaner nationalism as seen through the camera but rather about the slippages in intention and portrayal from Some Afrikaners Photographed (first published in 1971) and the later version of the book published in 2007. Its an interesting analysis of the politics of the South African English language Tatler magazine. Here was another form of fabrication and selective use of the past. A well written essay and the authors carry their argument rather well.

The politics of Afrikaner nationalism was fraught with controversy and mutated through time with shifts to the right by some or sticking in the centre. As the generations passed did Afrikaner nationalism not fragment? What happened to Afrikaner nationalism after 1994? If marginalisation fed nationalism should we not have expected to see more and not less of this brand of nationalism. How do we fit the nationalism of Oranje and Mrs Verwoerd into this account?

Overall each essay is worth reading and I wish I could give an overview of all the contributions. I suppose the weakness is some repetition (we hear that the Voortrekker Youth Movement was the Afrikaans equivalent of the Boy Scouts in three essays and the two introductions cover some of the same ground in recapping what lies ahead in each chapter. Oddly there is no epilogue or concluding chapter. Each essay has excellent bibliographic / source referencing details to show the authoritative research undertaken with generous NRF Funding. The colour photo illustrations are excellent and I compliment Paul Mills as supporting photographer. It is an attractive looking book and Wits University Press do a creditable job. As you can gather, each essay is worthy of a mini review in separate paragraph, but I think I have given enough of a flavour of this rich academic book and the controversies it addresses. This is a book that is a must purchase for any Africana library or South African art library.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.