Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In Episode 1 of this series (click here to read), mention was made of the agro-pastoralists (farmers who grew crops and kept livestock) who moved into the Magaliesberg region in about 225 AD. Scholars have categorised them as people of the "early iron age", as they possessed and made use of the technology needed for smelting and forging iron in order to make tools and weapons. They did not, however, build the more sophisticated settlements which were characteristic of the middle and late iron ages.

It is something of a mystery as to what became of these early iron age people. The dating techniques used by archaeologists indicate that they were present in the Broederstroom area up until about 450 AD. There is then a large gap in the archaeological record, and the next evidence of iron age peoples in the Magaliesberg region is dated at about 1100 AD. The most likely explanation (e.g. by Prof Tom Huffman) seems to be that the early iron age people moved away from the Magaliesberg, and that the middle iron age settlements are evidence of a second wave of immigrants who moved southwards from areas further north in Africa. Some scholars, however, including Prof Revil Mason, have maintained that the middle iron age people were direct descendants of those of the early iron age, and that we have not yet found the evidence of their continuous occupation of the Magaliesberg region from 450 AD to 1100 AD.

A young Revil Mason (Petra Mason)

The middle iron age people built larger settlements than their early iron age predecessors, in what is known as the "central cattle pattern". In these settlements, cattle kraals in the centre were surrounded and protected by the individual living areas of the people. This emphasises the value of cattle to the community. The settlements were located close to reliable water sources and areas of good grazing, but were not necessarily placed on higher ground. There is also no evidence that these middle iron age people built with stone; boundaries of living areas and kraals seem rather to have been constructed using wood from nearby trees (see Hall 2007, page 168).

Scholars are largely in agreement that late iron age people (present from about 1400 AD) were direct descendants of middle iron age people, and that the Tswana communities who still live in the Magaliesberg region today are in turn direct descendants of the late iron age people who were present in the area. The main differences between the middle iron age and late iron age are that in the late iron age, settlements were constructed on higher ground (usually hilltops), and that the walls of living areas and cattle kraals were constructed of stone. These differences point to a period of greater competition between communities, when cattle raiding had become a lot more common. More cattle raiding suggests a period when iron age people had flourished, with significant population growth leading to increased competition for resources (see Mason 1986, page 319).

During the late iron age, the low hills in the valley south of the Magaliesberg, formed from horizontal "sills" of igneous diabase rock, provided ideal locations for settlements. The hill provided the desired height for the settlement, and the diabase weathered into rocks of a very convenient size for building walls. The archaeological site known as "Olifantspoort 20/71" (i.e. site no. 20 first excavated in the year 1971) provides an excellent example of a late iron age settlement in the valley south of the Magaliesberg. This site was excavated by Prof Revil Mason over a period of five months in 1971, and we now turn to some of the details of his findings to illustrate the way of life in a late iron age Magaliesberg community.

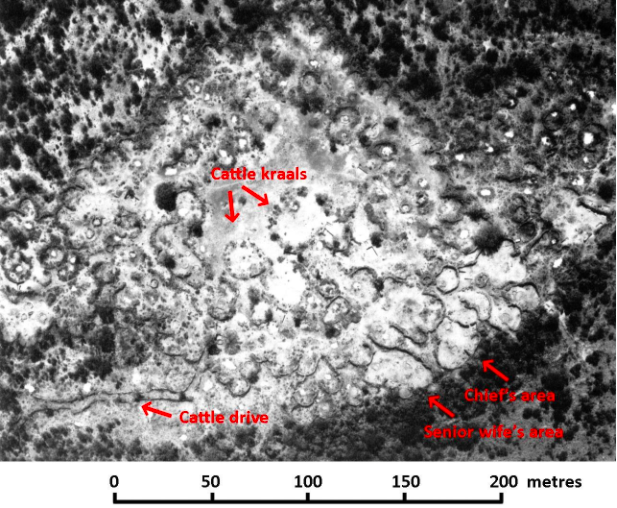

From radio carbon dating of ash heaps, Prof Mason dated the earliest stone walling at the site to about 1440 AD (Mason 1986, p. 373). Olifantspoort 20/71 follows the central cattle pattern typical of the late iron age, with several large cattle kraals in the centre. The settlement is enclosed by a scalloped stone wall, with each partly enclosed semicircular area forming the living area for a nuclear family. The chief's area is at the highest part of the hill, with larger fully enclosed living areas for himself and his wives. The walling in the chief's area is significantly higher than that in the rest of the settlement, with some of the walls being more than two metres in height.

Aerial photograph of the site Olifantspoort 20/71, with added notes. Adapted from Mason 1986, p.359.

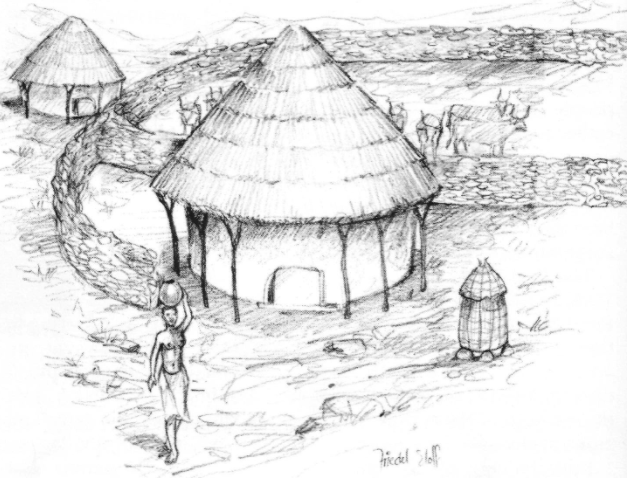

Most of the living areas in the settlement contain at least one hut floor, made of a compacted mixture of clay and cow dung ("daga"). The fact that these hut floors are still present almost 200 years after the settlement was vacated testifies to the durability of this building material. The huts were roughly circular, with a diameter of about two metres. The thatched roof was supported by thick tree branches embedded vertically in the ground. Underneath the roof, and making allowance for an outside veranda at the front of the dwelling, a wall was constructed of thin vertical branches placed closely together and then packed inside and out with a mixture of clay and cow dung. A small opening (approximately 45 cm square) was left at ground level for use as a door. Prof Mason found evidence that these huts were equipped with small "sliding doors" made of slate or wood (probably boekenhout) which ran in a slate channel (Mason 1986, p. 383). The dwellings were thus simple but secure. The method of construction was ideal for the climate, keeping heat out during summer and in during winter.

Illustration by Freidel Eloff of a late iron age settlement with huts and grain bin. From Carruthers 2014, page 210.

Inside, each hut had a fireplace in the centre, with the smoke moving through the thatch at the highest point of the roof. There was a small gap at the top of the perimeter wall, so ventilation was adequate. The interior walls and floor made of clay and cow dung were polished smooth using the same mixture. Some huts had raised platforms on which items could be stored, as well as vertical branches embedded in the floor, on which other items could be hung. Woven grass sleeping mats completed the furnishings of these dwellings. Huts were used mostly for sleeping, with almost all other daily activities being conducted on the veranda or outside the hut.

Clay and cow dung hut floor at the site Olifantspoort 20/71

There was a clear division of responsibility between men and women in the community. The main tasks of men were cattle herding, hunting and waging war, with a few individuals being entrusted with the skills of smelting and forging iron. The women in the community cared for their children, grew the crops, prepared and cooked the food, built the houses, and made containers and other items from clay. These were fired in open pits filled with grass which was set on fire. The resulting pottery, often decorated with designs, was extremely durable.

Each settlement had its kgosana, a junior chief who was subordinate to the kgosi or king of the entire community. One of the kgosana's most important responsibilities was deciding the disputes which inevitably occurred amongst members of the settlement. Minor disputes were usually heard and judged on the kgosana's veranda, which at Olifantspoort 20/71 was far larger than the veranda of any other hut (Mason 1986, p. 381). More serious disputes were decided by the elders of the community in an area known as the kgotla next to the kgosana's living area. For matters of the highest importance, all the men of the community would assemble in the open area in the middle of the settlement, when opportunity would be given to representatives of opposing viewpoints to present their case. After hearing the different viewpoints, the kgosana and his council of elders would discuss the matter, and a final decision would be made.

The importance of cattle to this group of people is seen not only from the large cattle kraals in the centre of the settlement, but also from the long "cattle drive", consisting of two parallel stone walls, which runs from the north-west corner of the settlement towards an open area outside the settlement where the cattle used to graze.

It is clear from the archaeological evidence that there was a late iron age community living at the site known as Olifantspoort 20/71 for several hundred years. Their occupation of the site came to an abrupt end with the Ndebele invasion of the Magaliesberg region under their king Mzilikazi, probably in 1827. At that stage, this Tswana community was probably a branch of the Bakwena ba Modimosana ba Mmatau people, with their king Kgaswane residing at a very large settlement known as Molokwane, about 30 km west of Olifantspoort. Large quantities of burnt thatching grass were found on the hut floors at Olifantspoort 20/71, but the only human remains found were in graves of the traditional Tswana pattern. The archaeological evidence thus points to the community having fled from the settlement before the Ndebele arrived, and so having avoided wholesale slaughter (see Mason 1986, p.416). The settlement was, however, burnt after their departure, and was never again occupied.

Main image: Stone walling (about 1.8 metres high) at a late iron age site in the Magaliesberg

Andre is involved in development of new exhibits and information panels for Kedar Heritage Lodge near Rustenburg. Kedar, located on Paul Kruger's farm Boekenhoutfontein, is home to one of the world's largest private collections of South African War artefacts, including firearms, swords, uniforms, medals, documents and many other items.

References and further reading

- Carruthers, Vincent: The Magaliesberg: Biosphere Edition. Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2014.

- Hall, Simon: "Tswana History in the Bankenveld" in A Search for Origins: Science, History and South Africa's "Cradle of Humankind". Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2007.

- Huffman, Prof Thomas: Handbook to the Iron Age: The Archaeology of Pre-Colonial Farming Societies in Southern Africa. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007.

- Mason, Prof Revil: Origins of Black People of Johannesburg and the Southern Western Central Transvaal: AD 350 - 1880. Occasional Paper no. 16 of the Archaeological Research Unit. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand, 1986.

- Mason, Prof Revil: Origins of the African People of the Johannesburg Area. Johannesburg: Skotaville Publishers, 1987.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.