Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Yeoville is one of the oldest suburbs of Johannesburg, established around 1890 soon after the discovery of gold. During the early 20th century, Yeoville (and neighbouring Bellevue) was a middle- and working-class hub for European immigrants, especially Jews. Then, under the apartheid Group Areas Act, Yeoville became a whites-only neighbourhood, although many coloured and Asian residents secretly took up residence there. Yeoville went through a funky, alternate phase during the 1980s, but this era is a thing of the past. This article is about tracking down a remnant of Yeoville’s multi-racial past by finding a shop that was once a thriving Rockey Street men’s outfitter business run by Mr K B Patel.

Taking photos in Yeoville in the 1980s

In 1988 I did a photojournalism course and our group went to Rockey Street in Yeoville to capture images of life on this street. I took photographs of Mr Patel and his tailoring and men’s outfitter shop. Since then, I haven’t been to Yeoville at all. I drove around recently to try and find out where Mr Patel’s shop used to be and I couldn’t find it because almost everything has changed. Many of the old shop fronts have been repurposed and covered up with new hoardings and signage and substantial and often brutal burglar bars. Metal roller doors abound and the mechanism for these doors often obscures any remaining vintage signage. Using my 1988 photographs, Google Earth and an actual visit, I was able to find Mr Patel’s original shop.

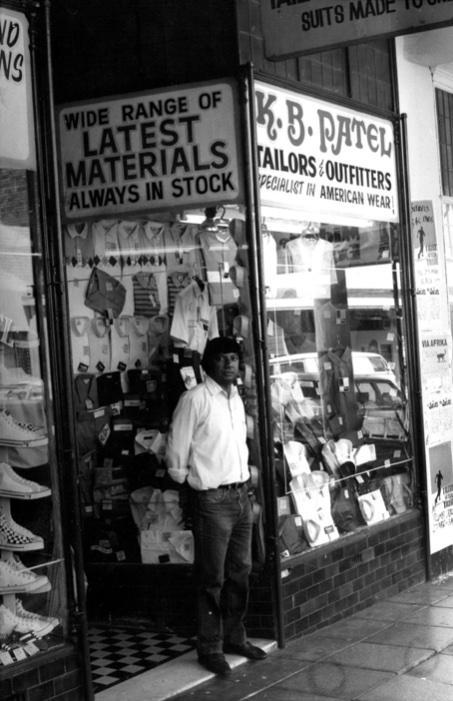

Mr Patel outside his shop in Rockey Street, Yeoville in 1988. (Sue Taylor)

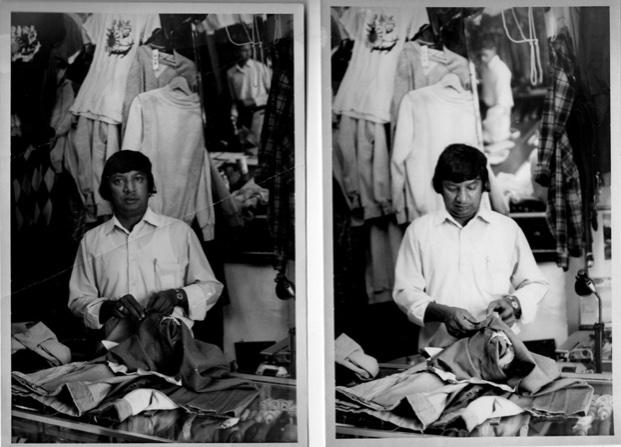

From these photographs, it can be seen that Mr Patel’s shop was well resourced, with an extensive ‘American’ men’s clothing and shoes stock. The signage for the shop was also beautifully done. Looking at the amount of repair work being done in the shop by Mr Patel, and numerous completed items hanging up in the shop, this was a very successful business.

Finding Mr Patel’s original shop

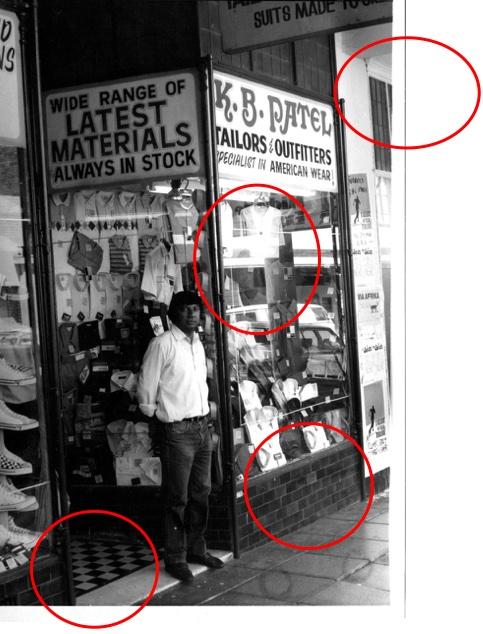

I selected four identifiers (see image below) from the above photographs to search Rockey Street for the long-ago locality of Mr Patel’s shop. The indicators included the inset shop doorway and white marble front step; the six rows of bottle green wall tiles below the front shop windows; and the place where the top right hand side (if facing the shop) of Mr Patel’s shop joins with an adjacent shop and showing a high window with burglar bars. This barred window to the right of the old shop was important to find to confirm that I had located the correct shop as other features had been removed. Reflected in the shop window were the concrete pillars characteristic of this row of shops, as well as a window from the building across the street, the huge Piccadilly centre with its upstairs apartments.

The four identifiers of Mr Patel's shop

Gathering evidence of the location of Mr Patel’s shop

Looking at my photograph and the reflections in the shop window and Google Earth street view, I determined that Mr Patel’s shop was Number 1 Rockey Street and is now the premises of a cell phone and shoe shop, as well as a barber shop. I went to this locality and chatted to the current shop keeper. He told me that he had been in the shop for eight years, and that all the nearby shops had been ‘renovated’ recently, which I could see largely meant that vintage features had been stripped out or covered up. In other similar shops in Rockey Street, the original wooden fittings have been replaced by aluminium window and door frames. The 2023 shop no longer has the original black and white tiles in the entrance foyer or the original signage, but otherwise is reasonably intact. The green front wall tiles facing the street and the black and white tiled entrance floor have been removed. The exterior of the shop shows that the original wooden door with glass panes, the window display areas and wooden window frames are still in place, as well as the sash window above the wooden door. The display windows still display shoes in a similar way to Mr Patel’s old shop. Otherwise, this shop is almost empty of stock. It has roller doors to protect it at night, as do most of the other small shops in the area.

Shop No. 1 Rockey Street, Yeoville in 2023 (Sue Taylor)

Indian immigration to the British colony

Indian immigration was allowed by the British government and groups of Indians arrived in 1860s to work in the Natal cane fields under gruelling conditions, with the idea that after five years they would return home. But at that time, other wealthier Indians arrived and as they had paid for their own passage to South Africa, they were independent, could start businesses and formed an independent Indian commercial class during colonial times. They found that the main needs at that time were food items and clothing and they set up shops in many small towns of Natal and other parts of South Africa to supply these items. Their first customers were intended to be other Indians, but they quickly came to monopolise trade with local Africans at that time. In Johannesburg, Indian tailors had already started to form their tailoring businesses around the early gold mines (late 1890s) and catered to Johannesburg’s growing black labour force.

Over the years, there were many cruel laws that restricted Indian movement and economic activities. For example, in 1891, the Volksraad in the Orange Free State passed a law expelling all Indians from the province. The Immigrants Regulations Act, No. 22 of 1913 prevented Indians from moving to other provinces, meaning that the majority of Indians were compelled to remain in Natal, with the greatest concentration being in and around Durban. The endeavours made by Indians to acquire and occupy property brought in its wake a great deal of anti-Indian legislation and propaganda. When the National Party won the 1948 general election, it started to pass a wide range of draconian apartheid laws which aimed to ensure racial separation of all aspects of political, social and economic life. The laws controlled the movements and economic activities of black people (or so-called non-whites, which included coloureds and Indians). Only in 1961, were Indians officially recognised as permanent part of the South African population.

Working with clothing and fabrics

During the apartheid era, racially-based group identities controlled all aspects of daily life. So-called non-whites were not permitted to live, own land or start businesses in areas reserved for whites. Indians and Asians were, however, allowed to practice a few types of businesses in white areas, one of which was work with fabrics, garments and tailoring.

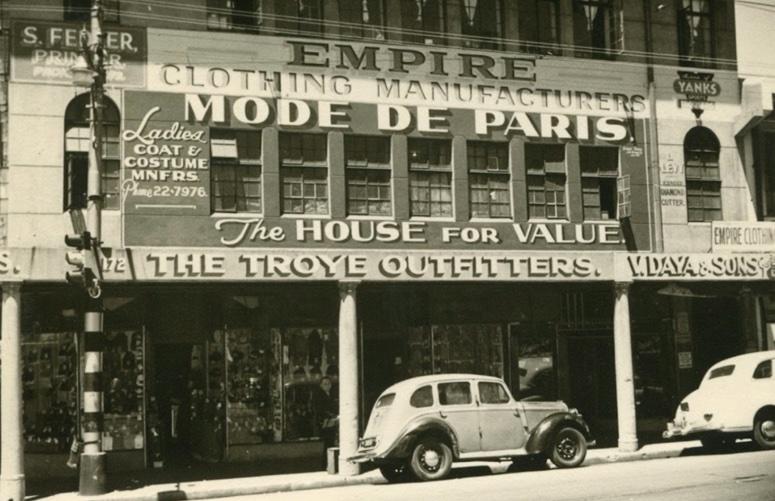

A typical men's outfitters of Johannesburg in the 1950s (Bath Family Archive). Note the display windows and the inset doorways which were typical of main street shops of this era.

During the early 20th century, Indian tailors either repaired clothing or produced made-to-measure pieces (usually trousers) for their Indian and African clients and many were active in Johannesburg around the gold mines and the now-old suburbs of Johannesburg. Many African clients favoured 'the American men’s look' and most of the brands stocked in the outfitters were imported from the US. The Indian men’s outfitters were predominantly family run businesses.

Even though Indian tailoring businesses were permitted under apartheid, the government meddled in deciding where these shops and businesses could operate. The destruction of Pageview in the 1970s and removal of many small fabric businesses to the newly built Oriental Plaza was an attempt to control these Indian businesses. By the time apartheid fell in 1994, the influx of international brands and cheap Chinese goods changed the way fashions were promoted and sold in Johannesburg (Nxedlana, no date), and these imports essentially wiped out the men’s outfitter as a business mode. Many men’s outfitters like Mr Patels’s shop in Yeoville are now long since closed down.

Main image: Two photos of Mr Patel hard at work inside his clothing shop. In addition to selling American fashions, Mr Patel and associates also did alterations and repairs. There is an image of another partner in the mirror on the top right hand side of both photographs. (Sue Taylor)

Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. She is a development consultant with experience in researching, writing and lecturing about sustainable development, climate change and social development issues in South Africa and Africa. She has worked in the biotechnology research sector, in nature conservation and in the NGO sector as a climate change activist, and more recently as a science writer. Her current interest is cities, slums and urban climate change adaptation.

Dr Taylor has recently written a book chapter: Google Earth augments viewing the spectacle of ruin in selected ‘in-between places’ of old industrial Johannesburg, in: Junctures 23, (2023), publication pending. She is one of the editors of a book on Phuthaditjhaba, an informal city in the former homeland of QwaQwa, South Africa, published in January 2023, and has also written one of the chapters discussing greening as a way of climate preparedness for towns and cities. The book is called Sustainable Futures in Southern Africa’s Mountains: Multiple Perspectives on an Emerging City, Editors: Andrea Membretti, Sue Jean Taylor, Jess L. Delves. Springer 2023. The book is available with open access here.

Sources

- Jamal Nxedlana (no date). Outfitters: Johannesburg’s Men’s–Fashion Museums. Bubblegum newsletter.

- SAHO (no date). Indian Passive Resistance in South Africa: 1946 – 1948. South African History Online.

- Nkosi M (2022). The pulsating beast that was Yeoville is now a rotten carcass. News24

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.