Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Hermanus, everyone agrees, is a seaside town. The names tell you that: the Old Harbour, the New Harbour, Voelklip Beach, Harbour Road, Poole's Bay, Kwaaiwater, the Klein River and Onrus lagoons – the list goes on.

Yet for well over a hundred years, Hermanus has had a surprisingly extensive history of contact with powered flight and aircraft. It all started just thirteen years after the Wright Brothers achieved the first 12 seconds of powered flight by human beings on 17 December 1903. In 1916, eighteen-year-old Henry Luyt, son of P John Luyt, the Marine and Riviera Hotels owner in Hermanus, left school and went off to join the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in England to fight in World War I.

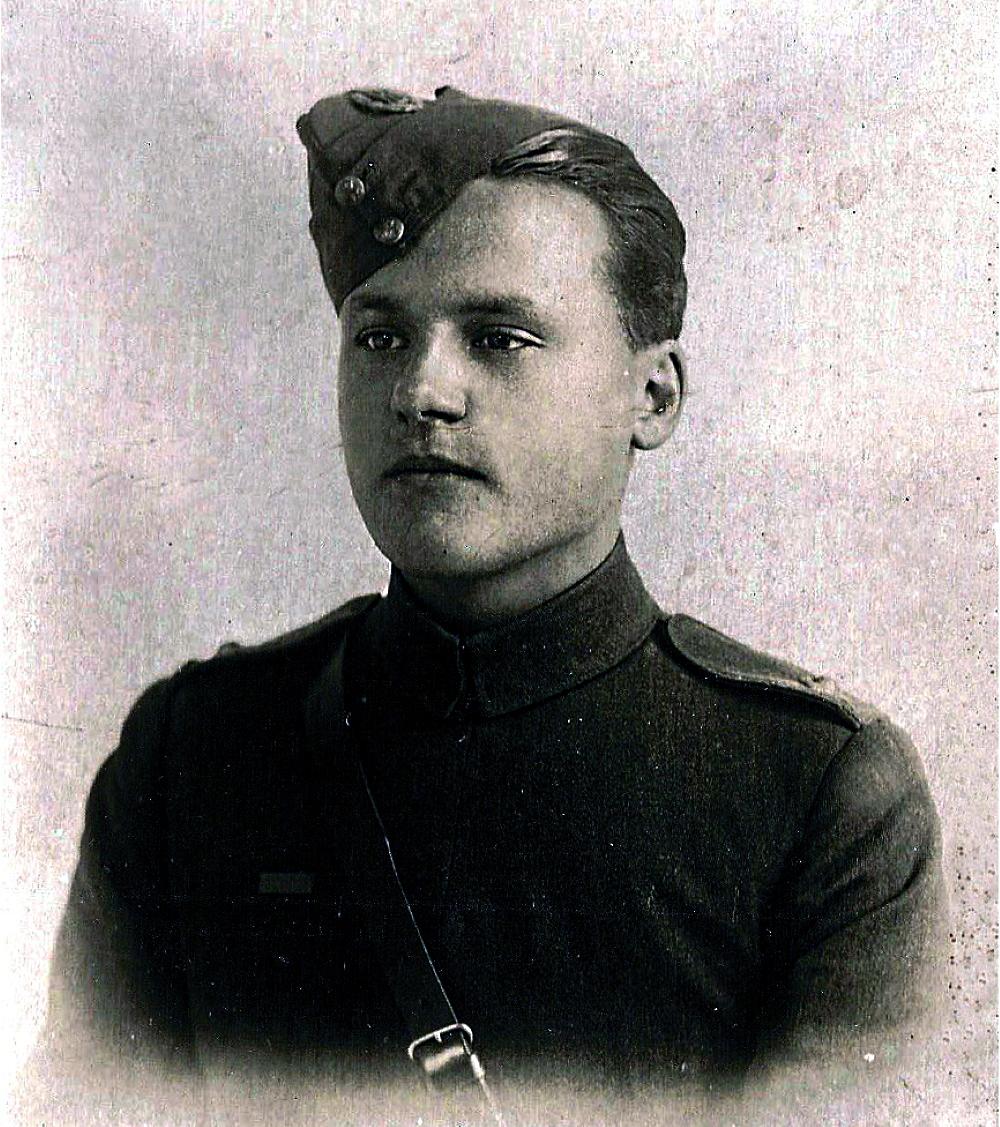

Henry Luyt during World War I (Old Harbour Museum Trust)

He received three months training and flew sorties over the German lines for a month or so, before being shot down by anti-aircraft fire. Fortunately, his plane landed upside down on an unoccupied enemy trench in Belgium, and he survived. He released himself from the upside-down position in which he had come to rest, evaded capture and returned to his work in the RFC.

In 1919, he returned to Hermanus, where his father persuaded him not to fly again –instead, he bought Henry a sports car that Henry named The Red Devil, and drove at high speeds around the Overberg and all the way to Cape Town.

Henry remained friendly with a circle of young men who did own planes, and, for most of the 1920s, they regularly flew to Hermanus during the 'season' (December and January), landed on Grotto Beach and then took astonished holidaymakers up for what were called 'flips' over Walker Bay and inland to the mountains. The area known as 'Die Plaat', on the western side of the Klein River mouth was regarded as the first 'airstrip' in Hermanus.

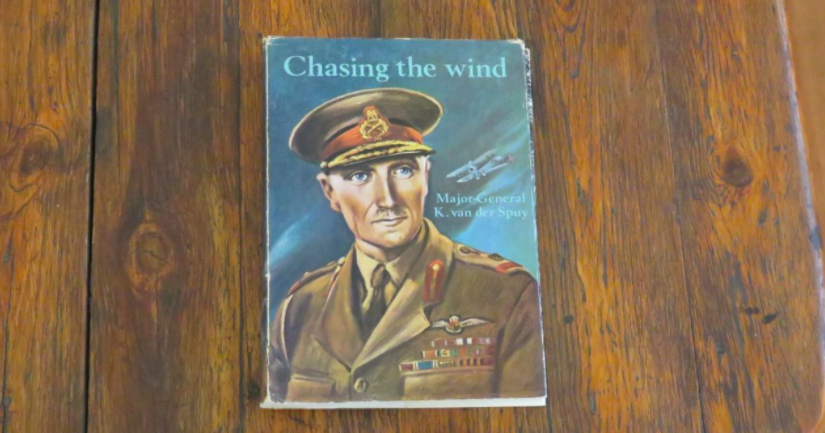

The South African Air Force was established in 1920, based at Zwartkop, with another base at Youngsfield near Cape Town. Closely involved in this development was Major-General Kenneth van der Spuy (1892 – 1991), a resident of Stellenbosch. He and his wife, famous horticulturist Una van der Spuy, were frequent visitors to the Marine Hotel in Hermanus, though he does not seem to have flown to the town or patrolled the area from the air- after all, he was on holiday.

Chasing the Wind by Kenneth van der Spuy

Later, van der Spuy became friendly with Sir Thomas Sopwith, perhaps the most famous aircraft designer and British aeroplane manufacturer in the 20th century. Sopwith owned extensive property in Voëlklip later in the century, notably a farm called Onderberg, up against the mountain in the vicinity of First Street.

Sir Thomas Sopwith (Wikipedia)

Henry Luyt's passion for planes got another boost in 1932 when the famous British female flyer Amy Johnson stayed at the Marine Hotel. She had just flown solo from London to Cape Town in a women's record time and was the darling of all the media. She had previously flown solo from London to Australia, also in record time and been awarded the title CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) by King George V. In 1936, she would repeat her flight from London to Cape Town, breaking the men's record as well as her own, but did not come to Hermanus that time. Sadly, she was to die in controversial circumstances in the early years of World War II. On a routine flight from the north of England to Oxford, her plane was seen way off course over the Thames Estuary, where she was observed to parachute down into the freezing water and disappear. Her body was never found, but some personal items confirmed that she had died there.

Amy Johnson (Our Generation)

In the early 1940s, the Royal Air Force established a flying boat base on the Bot River Estuary. Many sorties were flown against German U-boat operations along the South African East Coast using the famous Catalina flying boats. South African radar installations supported the Catalinas from Betty's Bay and other locations. Many of the RAF pilots stayed at the old Onrus Hotel during those years and were involved with the social life of Hermanus. Three are known to have married local women after the War and settled in Hermanus.

Cape Hangklip Radar Station (Robin Lee)

When the Onrus River's bridge was washed away in 1944, pilots and technicians from the Catalina squadron built a temporary bridge over the river. The town of Hermanus was not wholly cut off, and all traffic used this bridge for several months. Berdine Luyt was one of the first to cross when she returned to Hermanus after a visit to Johannesburg for surgery to correct a sight defect she had had since birth. On 18 September 1944, she records in her diary;

Back home at last! Mr Mendell, a very charming man from Cape Town, brought me through by car. The arrangement was that he would leave his car at the garage at Onrust and we would walk across the temporary plank bridge that has been constructed over the river: Mother's car would meet us on the other side, with a member of the hotel staff to carry our luggage. However, when we reached Onrust, we heard that an RAF lorry had just crossed on the plank bridge, and Mr Mendell thought that what a lorry could do his car could also. So he drove slowly over with some trepidation – the temporary bridge being simply a raft thrown across the river and the banks on either side being very steep. We passed the lorry with a triumphant toot and drove on to Hermanus, receiving a warm welcome at home…

Berdine Luyt (Old Harbour Museum Trust)

During World War II Hermanus was the preferred leave destination of thousands of Allied servicemen passing through Cape Town on their way to various battlefields in Africa, the Middle East and the Far East. On 5 November 1944, two pilots from the SAAF caused an uproar in the town. As usual, Berdine Luyt was there to record the incident:

We seem to have had the entire personnel of Young's Field here at one time or another during the last few weeks; mostly restive young boys waiting to go up north. There were four SAAF pilots here last week, and they spent most of their time acting as escorts for Connie [Berdine's youngest sister] and Betty van Rhyn (our cousin, here on holiday). They left on Wednesday and promised to "shoot up" the hotel on their next coastal patrol.

The next morning at about ten o'clock we heard planes zooming over the hotel, and we ran outside to see what was happening. There were two SAAF planes flying low over the roof, apparently with every intention of landing on the balcony. It was very exciting and a wonderful display of low flying and split-second control. All the visitors ran outside to watch, the indoors staff were having pleasurable palpitations at the upstairs windows, and the garden staff (who had been peacefully weeding the lawns) were lying flat on the ground with their arms over their heads and moaning.

Connie and Betty stood on the edge of the cliff, dancing with excitement and waving coloured scarves. The planes flew level with the cliff then, and Dennis (one of the pilots) showed a green and red light as he said he would.

Then the planes turned and flew right out to sea. Making for opposite ends of the bay, they banked and came straight at the hotel and each other at terrific speed. We held our breaths in horror and waited for the crash, but at the last split second the one plane curved sharply sideways and upwards and the other, below it, missed the hotel roof by about an inch. They then treated us to an exhibit of low flying over the grounds, below the telegraph wires, that had us all joining the gardeners flat on the grass. It was marvellous flying but nerve-wracking to watch.

Then they flew out to sea again and showed us some trick flying, and shortly after this Mother stormed out of the hotel and dragged Connie and Betty inside, demanding furiously if they wanted those crazy young men to kill themselves. With the main reason for their perilous activities removed, the planes "shot up" the hotel once more, waggled their wings in farewell and took off on coastal patrol.

There were repercussions. The pilots were reported to their OC (Commanding Officer) by Air Vice-Marshall Meredith, who was staying in a cottage nearby. Dennis phoned Connie later and told her that they had been on the carpet, but their O.C. was a most understanding man and would only give them squadron punishment (low flying being entirely forbidden) if the event could be hushed up a bit. Otherwise, it might be serious, especially as the AVM was involved.

Dennis and Charles got special leave to come down and see the Air Vice-Marshall. They turned up at the hotel, spitted and polished to the last button and quivering with apprehension. Ginger (Berdine's brother-in-law) gave them a pep talk, said he had met the AVM, and he was quite a decent chap, told them to tell the truth and not any fancy stories, and sent them off to their interview still nervous but not quite so apprehensive.

They came back a little later, much relieved, to say the AVM had been very decent about the whole thing and had agreed not to make an issue of it.

November 1944 seems to have been a busy month for aviation-related events in Hermanus. Buzzing of the Marine Hotel was soon followed by a hide-and-seek game with the same Air Vice Marshall who had let the pilots off so lightly. Berdine Luyt records the episode in the slangy way she reserved for people and events that she regarded as pompous and needed taking down a bit:

We have had an anxious – but entertaining – weekend, due to the disappearance of the Air Vice-Marshall.

Air Vice-Marshall Sir Charles Meredith has been staying in the Monkhouse's cottage near the hotel for some weeks and has been having his meals at the Marine. He was down here from Rhodesia for a rest, so has been living very quietly. On Friday Charles told us he was going to Cape Town for the weekend and would appreciate a lift there on Saturday if we heard of anyone going up by car. Sandy Grant (who knows everything) told us late on Friday afternoon that a Mr Waters, staying at the Central Hotel, was leaving at 8.30 a.m. on Saturday morning and would be glad to take the AVM into town with him. We told Charles on Friday evening, but he did not appear keen and said he might perhaps go in by train. So we ordered sandwiches for him, and then we all went to Henry Horne's cottage for a party so did not see him again.

On Saturday morning, the sandwiches came through to the office, but Charles never collected them, so we presumed he had changed his mind and taken the lift after all. At about eleven o'clock a Squadron Leader of the RAF telephoned from Cape Town. Could we tell him whether the AVM was coming into Cape Town that day or not? I explained about the lift and said that, since he had not yet arrived, he might possibly have taken the train after all and, in which case, he would not arrive in town until the afternoon.

At 2 p.m. the Squadron Leader telephoned again. He had a very urgent message for the AVM – had we any idea where he was or where he could be? As he hadn't yet arrived in town, he could not possibly have left at 8.30 a.m. with Mr Waters. The SL said he would meet the Caledon train at quarter to four, and if we heard anything further before, would we phone him. Enquiries at the Central Hotel confirmed that Mr Waters had left at 8.30 a.m. and alone.

On the other hand, the local Stationmaster said that the AVM definitely hadn't been on the bus. Checking his cottage, we found it locked up and no one here. Mr Waters, now presumably in Cape Town, was not contactable.

It all seemed most odd, and everyone was forthcoming with suggestions as to what could have happened. Paddy thought we should break into the cottage as Charles might have been murdered by the Obs (Ossewa Brandwag) and be lying there weltering in gore; Ginger said that we should get a warrant to search "Crailings" as he might be an unwilling prisoner of Pearl Tankerville-Chamberlain (who has been chasing him for some time). Connie said Mr Waters had no doubt kidnapped him and would hold him for ransom in some hideout.

Then a message came from the Central Hotel. Charles had left with Mr Waters after all. They gave me his address, and I telephoned him. Mr Waters (who had a lovely voice and was charming about the whole thing) sounded surprised and said he had dropped the AVM in Adderley Street at precisely 11 o'clock that morning. I telephoned the Squadron Leader, who groaned into the receiver and said he would make enquiries in town.

On Sunday morning the SL telephoned again, almost in tears. Had we heard from the AVM? No? Well, he had been in touch with every single person in Cape Town who might have seen or who might know where Charles was, with all the RAF, SAAF and military stations and camps, with every single hotel, club and hospital. Everywhere a complete blank. Now both the RAF and SAAF were out searching for him, so far with no result. Could we suggest anything more? We couldn't, and he rang off, sounding infinitely depressed.

Could Charles really have been abducted? We spent the rest of the day exploring this fascinating possibility.

On Monday morning, one of the stewards came to the office to say that the Air Vice-Marshall had just come into the bar and was having a beer. A little later, he walked into the hall, looking rather sheepish, to confront the accusing eyes of us all lined up behind the reception counter. We took him into (Room) No. 3 for explanations. It appears he had spent the weekend with the Navy at Simonstown and had not given the Squadron Leader his address (as he should have done). On Monday morning he was sitting peacefully in the Caledon train, reading a newspaper, when he heard a commotion on the platform. The Squadron Leader appeared, accompanied by the Stationmaster, several lesser officers and officials and a couple of porters, and dragged him almost forcibly from the train.

Charles was surprised at the fuss and made matters worse by laughing when the Squadron Leader gave him a pithy account of searchers combing the Peninsula for him all weekend. A very urgent message had come from Salisbury, and he had to return immediately; a plane had been sent for him and was now ready and waiting at Young's Field.

Charles protested. He said he would be ready to leave about Wednesday or Thursday; that he had to pack and close the cottage; that no, he couldn't let anyone pack for him; and finally, cornered, that he refused to leave immediately without going to Hermanus first. The Squadron Leader insisted he go by car however and that the driver wait and bring him back to town. So Charles packed and tidied and sprinkled everything knee-deep in mothballs, and then came over and had a farewell drink with us. The car left at about six o'clock, and we thought of telephoning the Squadron Leader and telling him that the Air Vice-Marshall had disappeared again, but decided we had better not play tricks on the RAF.

People I have interviewed have told me that the Imperial Airways flying boat service between the UK and South Africa in the 1940s and 1950s sometimes made a stop at the Bot River Estuary. I have not been able to verify this information, and it seems such a stop would be too soon after take off from Cape Town and too soon before landing at Cape Town. I continue to look for confirmation. Readers may be interested to know that the first weekly flights took ten days, with eighteen stops and lots of low-level sightseeing opportunities. In 1938 flights were doubled to two a week. By 1950, the final year of operation, the flight time was down to 4 days on the route Cape Town – Vaal Dam - Port Bell (Uganda) - Khartoum- Cairo – Augusta (Sicily) – Southampton and train to London.

In flight service flying boats

In the 1960s, Hermanus got its own airstrip, built where part of the suburb of Zwehlihle is now. Many visitors flew into Hermanus on holiday, rather than drive from Cape Town and other parts of South Africa. Local flying enthusiasts kept hangars for private planes there and flew for pleasure. Readers on social media responded with stories of their own. Mary Krone wrote:

I landed at the Hermanus airstrip in the 1970s on one of my early training flights. What made it so special was that lots of tall trees surrounded the airstrip and it was rather a windy/gusty day. The "long & the short" of it was that one had to "crab" it in (i.e. keep the nose of the plane facing the 'wrong way' against the wind ) until you were just at the height of the surrounding trees at which point you had to adjust and aim at the runway itself quickly, or else you would have crashed into the trees due to the sudden loss of wind below the height of the trees. Scary stuff at the time, but exhilarating all the same.

Andrew Embleton recalled several aspects of the airstrip in Hermanus, especially the fact that the Harvard planes used by the SAAF in the 1970s and 1980s, often landed there during training flights. Andrew's father was a friend of the elusive Air Vice-Marshal Meredith.

Harvard at Hermanus (Andrew Embleton)

As pressure for housing in the Zwelihle area grew in the 1970s, the airstrip became surrounded by human settlement. Acts of sabotage of the hangars and the planes began. Avril Sinclair noted:

I have been living in Hermanus since 1987. My first visit here was by air, my first husband piloting the plane. We landed at the airstrip in about 1977, shortly before the place was vandalised.

The airstrip finally ceased to function in the 1990s. Adrian Louw recalled that 'the airstrip functioned into 1992 at least when an airshow was held there. I managed to cadge a trip (to the show) in a rebuilt Super Dakota. The legendary Scully and famous announcers were there'.

Powered flight retained a link with Hermanus, even though the airstrip was no longer in operation. Evan Austin established the air charter company African Wings and recalled the more recent days of flight from an airfield near Stanford:

My parents were Capetonians who moved to Pretoria in their twenties and lived on a farm where we grew up. My father flew as a means of travelling the length and breadth of South Africa with his family on holidays to every wild place imaginable in Southern Africa.

In 1973 during a visit to Cape Town we drove out to Hermanus and Dad bought a holiday house in Westcliff. After that, the whole family would pile into the aircraft on the Pretoria farm and fly to Hermanus for the Christmas Holiday.

I moved to Hermanus in 1993 as a resident. I kept my aircraft on the Hermanus runway until it became untenable, after which I moved it to Weltevrede airfield in Stanford, which was owned by Jacko Jackson, an ex airways pilot. I started African Wings, an air charter company with myself as the single owner / pilot / booking agent / aircraft washer. Had many enjoyable years flying whale-watching flights with my Cessna 175 and doing Namibia / Botswana private flying safaris from SA in a Mooney 201. The best ten years of my life. Then, stupidly sold the business to my brother and got a real job. African Wings is still doing whale-watching / scenic flights out of Weltevrede, so Hermanus still has its own airline. (See the whole story on www.africanwings.co.za)

I have been seriously told that the massive widening and straightening of Seventh Street in Voëlklip in the 1960s was done to provide an emergency runway for Mirages of the SAAF, in case other sites were unavailable because of enemy action. I have not been able to verify this fact.

Powered flight is less evident in Hermanus in the 21st century. The road from Cape Town has been improved continuously and the driving time cut down, and tourists come by that route. From time to time, helicopters ferry in the really affluent visitors, usually landing at the Marine Hotel.

Every year, the whale count takes place from fixed-wing aircraft that pass the town a few hundred metres offshore, but seldom fly over commercial or residential areas. They operate from Stanford. Very occasionally, jet fighters from de Hoop flash across the consciousness of residents and tourists.

Autogyro flights by environmental photographers zoom in and out along the coast, looking for specific target shots or images that capture the beauty of the coastline.

Inland, helicopters also fly more frequently as the summer fire season sets in. They dip into one or more of the freshwater dams to fill their buckets and then rush off to help stem the spread of the fire. They maintain a practical link between powered flight and Hermanus but would see it as a failure to control the fire if they were forced to come too close to town. I have watched them dipping their buckets into the Rockfill Dam, one of the famous Three Dams that once supplied most of Hermanus with water.

Increasingly, drones fly the skies over the coast and out to sea, to catch the ultimate publicity image for the next AirB&B website or a new book about Hermanus. They must be careful, as, on any given day, there are many more paragliders hanging over the town than powered aircraft passing over it. Powered flight and Hermanus now intersect hardly at all. But, the history remains.

Dr Robin Lee retired to Hermanus in 2001 after a career in the academic world and working in NGOs. In 2003 he started the University of the Third Age in the town and is involved in teaching and administrative work on a voluntary basis. In 2012 he joined a group that wished to formalise the study of the history of the area. This group is now known as the Hermanus History Society. Click here for details of the activities of the Society.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.