Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

We are honoured to publish a portion of the St David's Jubilee Book 'A Courageous Journey' revealing the fascinating early history of this well known Johannesburg school. Unless otherwise stated all photos are from the book. Copies of 'A Courageous Journey' can be ordered from Julie Egenrieder, researcher/archivist at St David's - egenriederj@STDavids.co.za.

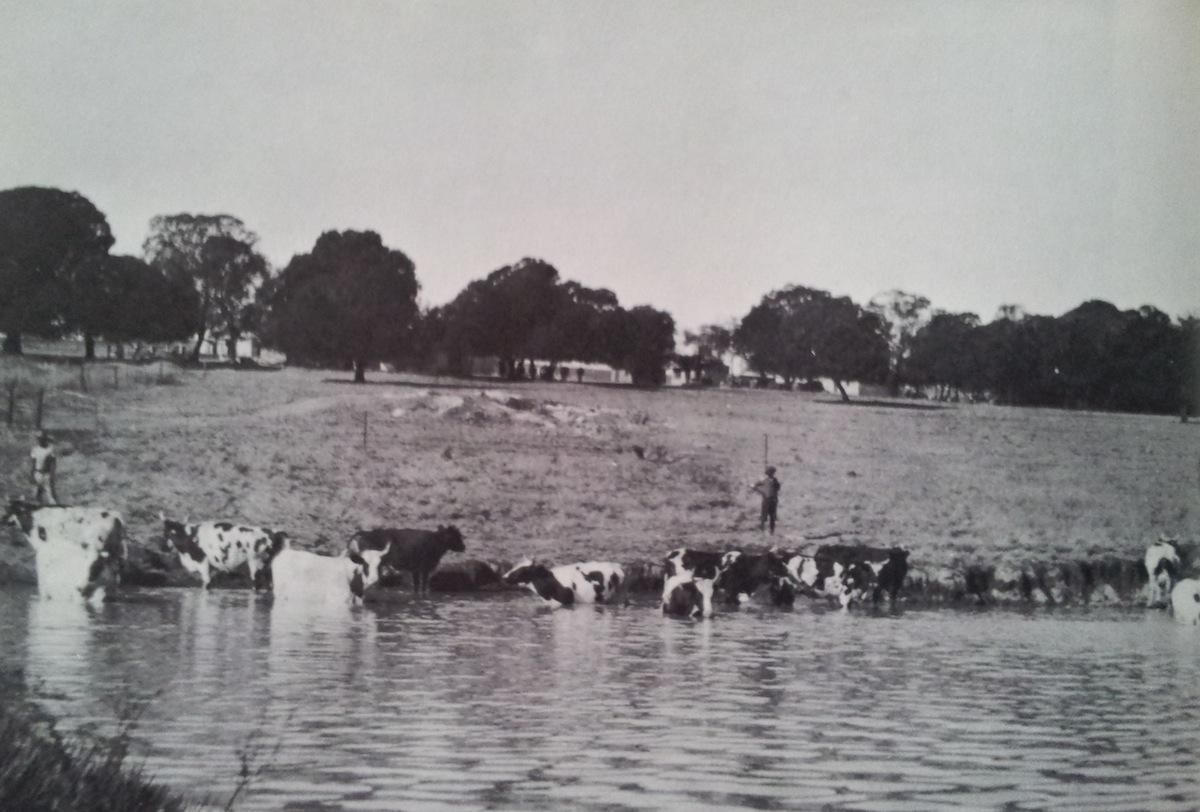

It must have seemed a strange place to start a school. The site was outside the city limits, a mile from the nearest bus terminus. The neighbours were mainly smallholders farming fruit and flowers, milk and chickens for the burgeoning city of Johannesburg. Orchards grew where Sandton City now sprawls; Benmore Gardens was Montague Simpson’s Benmore Farm, famous for its herd of prizewinning Ayrshire cattle. Close by was the Inanda Club, home to the Johannesburg Polo Club, but also home to the Rand Hunt that had held its first meet but a few years before, riding over farms and open land. The old farm, Zyferfontein, which had once belonged to Sir Edward Solomon, had by this time been proclaimed as the residential township of Inanda, but it was thinly settled.

Old photo of Benmore Farm (Wagon-Tracks and Orchards)

Benmore Farm plaque unveiling at Crawford College (The Heritage Portal)

It was also a strange time to be starting a school. When the doors first opened in January 1941, Hitler had more or less completed his conquest of Europe; France had fallen and Britain stood alone against the might of Nazi Germany. The future was decidedly insecure. Although the South African government, a coalition headed by Jan Smuts, supported the war and some 200 000 white male volunteers had gone to fight along with 125 000 recruits from other races, Dr Daniel Malan’s Purified National Party waited in the wings, quietly confident that South Africa’s participation in the war would prove to be a mistake. The more extreme Ossewa Brandwag did its best to sabotage the war effort and mobilise the volk in anticipation of a German victory – something that must have looked extremely likely in January 1941.

As they had done in the First World War, past pupils of the Marist schools in South Africa volunteered for service. The roll of those who died between 1939 and 1945 numbers in excess of 150, more than half of whom had been to school at Marist Observatory, while over a quarter were from St Charles in Pietermaritzburg. The places where they mostly lie tell the story of their war: Tobruk, Sidi Rezegh, El Alamein, Benghazi, Castiglione, Rome, Florence . . . But their graves can also be found as far afield as Kenya, Sudan, Liberia, Crete, Malta, Yugoslavia and Burma.

Those who had volunteered for the air force suffered the highest rate of attrition, with an unfortunate number of pilots being killed in training or in accidents.

Back at home, the war brought different challenges. While there was little of the dramatic austerity that characterised Britain during the war years, there were still serious shortages that hampered the creation of a new school some distance out of town. The most significant of these was the shortage of fuel as a result of the Japanese threat to oil tankers.

Fuel rationing was introduced in 1942, allowing each motorist enough fuel to travel a maximum of 640km a month. New light bulbs and car batteries could only be bought if the old ones were brought in to exchange; razor blades had to last indefinitely, while bottles and car tyres proved difficult to find. Many manufactured products that had been imported from Europe, and from England in particular, simply vanished from the shelves. All this was to greatly stimulate the growth of local industry but this took time, and the war effort absorbed much-needed food, metals and clothing. By 1945 basics such as sugar, tea, butter, rice and meat were also in short supply.

But the Marist brothers were not afraid to take risks. After all, they had been the first to open a school for boys in Johannesburg when it was hardly even a town, let alone a city. Nor had they had any guarantees of success when they did so. They simply opened their doors at their premises in Koch Street and waited for pupils to arrive. They did arrive. First, a solitary Peter Busschau, whose descendants were to follow him at the Marist brothers’ schools, and then more pupils came, and then still more.

It was from these humble origins that the Marist schools in Johannesburg grew. The demand was such that a new school was started in Observatory in 1924, now known as Sacred Heart College. Then came the plan to start the third school, to the north of the city, to cater for the junior boarders of Koch Street.

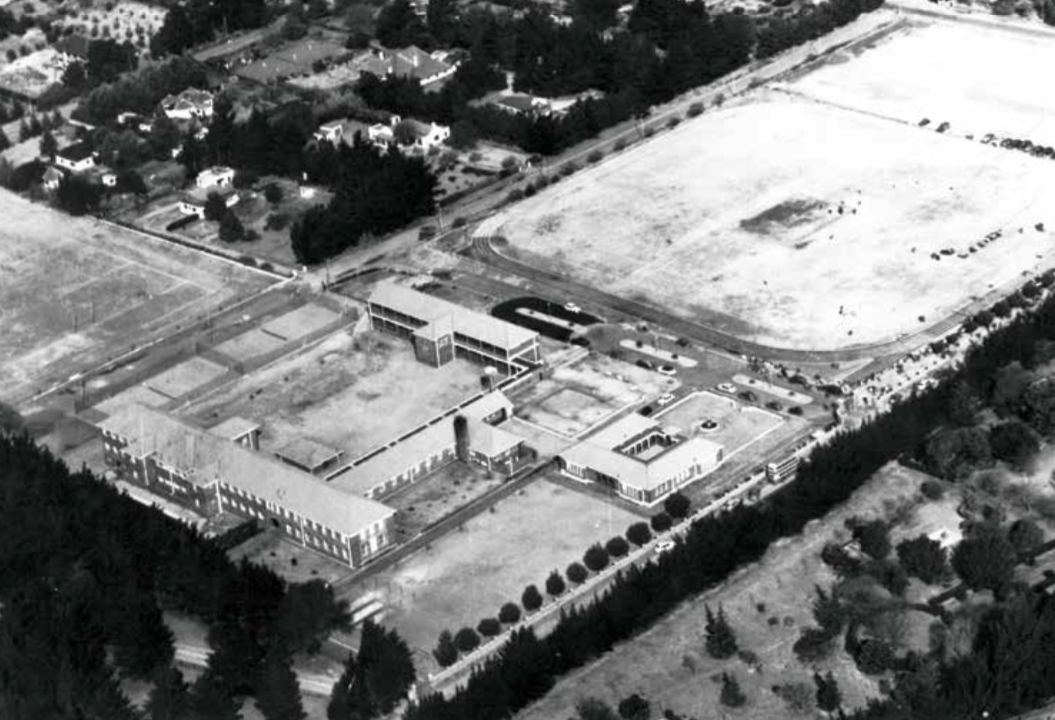

So, in spite of the challenges of the time the brothers, under the leadership of Brother Osmond, proved to be not only courageous in starting this new venture at this time, but also resourceful. The Provincial Council clearly saw the project as a priority and in order to avoid the strong threat of rising costs, building operations went ahead in 1940, as planned, at a site in Inanda.

Inanda wasn’t the first site that the brothers had considered. They had turned down seven acres on Cradock Avenue in Rosebank because it was too small; they had also rejected an 18-acre option in Hyde Park. The Inanda property, which included a cottage and some adjoining land, was 21 acres. It cost the princely sum of £12 476. Whether the brothers also had their eyes on the neighbouring smallholdings is not known, but it proved to be an inspired choice as there was potential space for future expansion. According to the records, it was also considered “one of the healthiest and most picturesque parts of Johannesburg”.

The original plan was that Inanda would cater for the junior boarders of Koch Street and Observatory. Numbers at these two schools had grown so significantly that they were turning applicants away. Inanda, it was thought, would relieve the pressure. The first buildings were to house a kindergarten, Grades 1 and 2 and Standards 1 and 2. The kindergarten opened in 1941, during which year the primary section was completed. During 1942, the boarding facilities were built and Brother Walstan was appointed principal. When the boarding school opened in January 1943, there were 176 boarders out of a total school roll of 200. Boarding fees were £21 a term for pupils under 12 years of age, and £24 a term for pupils older than 12. Grades would cost £6 6s a term while the senior classes cost £9 9s.

By this time, it was clear that the new school was much in demand and that it was going to be more than just a Prep School for the boarders of the other two Johannesburg schools. Until the opening of St Stithians in 1953, there was no other boys’ high school serving the farms and gentlemen’s estates north of the city limits. As a result, it was announced that a high school class would be added each year until matriculation had been reached. Additional facilities such as science laboratories and a school hall were planned to cater for this new vision of what the school was to become.

At the official opening on 27 January 1943, Brother Osmond spoke of the importance of the existence of private schools in any education system. They served, he said, as a guarantee against the kind of indoctrination and totalitarianism that had happened in Nazi Germany. His words proved to be prophetic. Catholic schools in general, and Marist schools in particular, were to stand out against the apartheid system and were to provide an alternative vision of society to that of the state schools. His accompanying pleas for greater state financial assistance for private schools were prophetic in a different way. They have been echoed down the years, only to fall on a succession of equally deaf ears.

General JJ Pienaar, Administrator of the then Transvaal, did the honour of unveiling the foundation stones (one in English; one in Afrikaans), while Bishop David O’Leary OMI, Vicar Apostolate of the Transvaal, blessed the building. He, too, called for state financial support for Catholic schools in the Transvaal, and praised the “undaunted courage and determination” of the Marist brothers who had made an invaluable contribution as pioneers of education in South Africa. Bishop O’Leary, who had given the necessary permission to the brothers to open the new school, left a further legacy as “Inanda” was officially named St David’s after the bishop’s patron saint. It was to be some time, however, before that name was in general use, and for many years the Johannesburg schools were referred to as ”Marist Inanda” and ”Marist Observatory” (more commonly, just ”Obs”).

JJ Pienaar at the official opening of the school

Although The Maristonian referred to Inanda as the “baby” Marist College, by 1944 it was beginning to look less like a pioneering venture and more like a regular school. The school had its first resident chaplain, Father Canisius OFM, and a chapel was planned, which came into full service in 1947. The Reverend Brother Urban, who had originally been brought to South Africa to be the Brother Provincial, had replaced the pioneering Brothers Walstan and Leopold as headmaster. The U13 soccer team had won its league the previous year, the swimming pool was open and the first annual swimming gala took place; there was gym equipment and playground equipment, which, along with the Owen Sims Trophy for the overall winning house in all branches of sport, had been donated by Mr Asher Swede. This imposing trophy was won for the first time, in 1944, by Benedict House.

Inanda Swim Bath

By 1946, the Science laboratory was ready and the College had its first Junior Certificate (now Grade 10) class. The boys ran their first cross-country race, estimated at around 13 kilometres “over the veld” to Tara Hospital and back. The winner, Manuel Gonsalves, made the distance in only 45 minutes. Mr R Freemantle donated the cups for the senior and junior athletics Victor Ludorum. In another first, these were awarded to Frank McGrath and Don Rethman respectively.

The main house at Tara (The Heritage Portal)

The Physical Education teacher, Mr Harry Best, introduced boxing as a school sport, which flourished for a while and even included inter-house tournaments. But the major sporting development of 1947 was the introduction of rugby. Initially, practices were held at Kent Park (which became the Wanderers Club) until the College developed its own fields. Coached by the heavy-smoking ex-Western Province player, Brother Alban, the team played its first match that year, losing 11-0 to Houghton College. In the same year, competitive cricket matches were organised for the first time. Despite the batsmen being “somewhat overawed”, the team felt confident enough to compete at 1st XI level. Another first was the inter-college athletics meeting with CBC Boksburg and Marist Observatory.

Boxing punchbags – gift of Owen Sims

1st XV rugby 1949

At least one long-standing tradition owes its existence to the sporting activities of this period. The boys felt that the war cry that they were using was rather tame and Don Rethman asked Brother Edwin and Brother Alban if they could change it. One night after supper, Rethman and the school chef, the indomitable Piet Ncwane, sat down in the dining room and composed Kalamazumba. It was first used in 1950 at a match against St Charles, which Inanda won. The war cry was given the credit for the victory and it has been used ever since.

But it was not just about sport. Although a number of past pupils from this period have commented about the paucity of cultural activities, a debating society known as the Inanda Forum was started in 1948, meeting on Sunday evenings, and once Mr Drummond Bell had been appointed to the staff in 1950, he taught singing, trained a choir and, later, regularly produced Gilbert and Sullivan musicals at the school.

The College reached maturity in 1948 when the first matriculants sat for their public examinations, which they wrote through the University of South Africa (later the Joint Matriculation Board, now the Independent Examination Board). The first Honours blazers were awarded to members of this first matric class. The recipients were Edward Barale, Luiz da Cruz, Christopher Clarke, Hugh Gearing, Manuel Gonsalves, Harry Hart, Errol Hulse, Keith Kennaugh and Frank McGrath. A further honour was added with the presentation of the BR Hunt School Scholarship Trophy by Mrs Gertrude Hunt, in memory of her late husband. The trophy was to be awarded to the Dux of the school based on the matric results. It was first presented to Peter Bailey in 1949.

Coincidentally, on the same day on which the first matric paper was written, work began levelling and setting out the playing fields and tennis courts. Even at this stage, no expense was spared, firmly establishing Inanda’s reputation for its sports facilities and laying the foundation for its later prowess as a sporting school. A turf wicket was laid down in the centre of a five-acre cricket ground, the remainder of which was planted with kikuyu for the winter sports. Boys were asked to volunteer to plant the grass on the fields. According to one of its members, Alf Lamberti (1951), this “Labour Gang” was rewarded with bacon, eggs, toast and marmalade for Sunday breakfast, and were allowed to choose the Saturday night movies that were shown on the school’s newly acquired projector. By the end of 1949, the fields were practically ready for use.

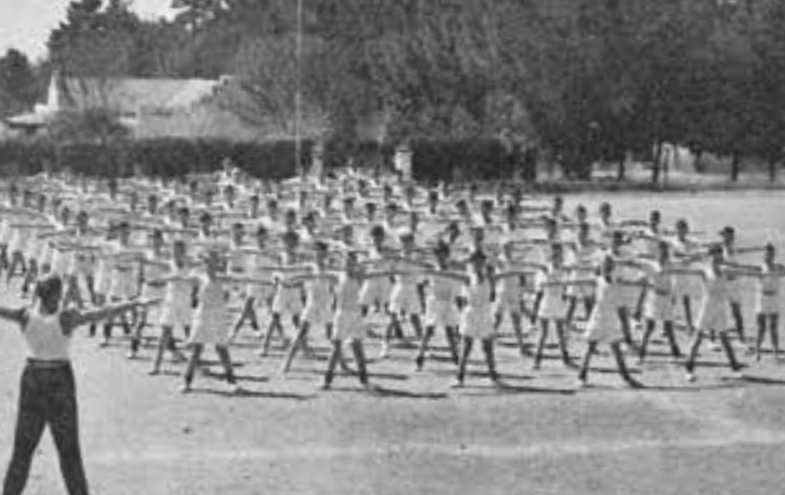

Gym group with instructor Harry Best

For those boys who attended St David’s as day boys, getting to school was often quite a challenge. The bus from town only ran as far as the Dunkeld terminus, on the corner of Oxford Road and Corlett Drive, leaving a mile- long walk to Inanda. This Dunkeld bus only ran once an hour in those early days, so missing it posed a rather serious problem. Quite a few of the boys cycled to school along the dirt roads that came in from further north. One boy, who lived in Sandhurst, even came to school on a horse. Peter Loffell, who started at St David’s in 1948, remembers having to wait at the McGill Love farm next door to the school for his father to pick him up, until he too was considered old enough to ride a bike. By the 1960s a municipal bus service ran once a day from Rivonia to Rosebank and back. This bus, driven for many years by the legendary “Ben”, who used to park the bus overnight at his house in Rivonia, dropped the boys at Inanda at 7. 30am and collected them at 4pm on his journey home.

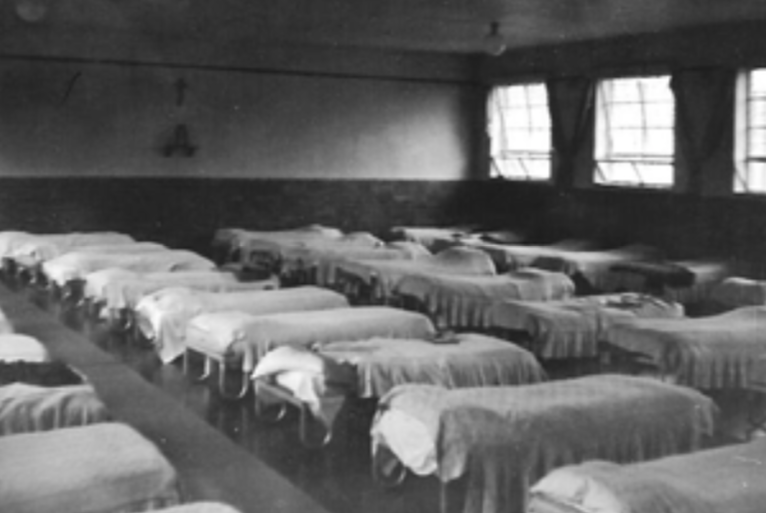

But the vast majority of boys at St David’s were boarders. Dormitories were large, housing some 50 boys each; meals were most probably adequate – “army-style food”, according to one old boy, including “army biscuits, lumpy porridge, brown bread and peanut butter” (Jock Loseby, 1951). During the war there was no white bread available, nor was there any butter apart from peanut butter. According to Billy Williams (1945), there was also a shortage of cups and they had to drink out of glass beer bottles that had had the tops removed and the sides bevelled. He describes the food as generally having been good, but the boarders were always hungry, as boarders always are, and they constantly pestered the day boys for a share of their sandwiches. Another old boy remembers playing a practical joke on the boarders one day, by giving them Brylcreem sandwiches with a chilli in the middle.

Dormitories circa 1948

For some of the boarders, the solution was more drastic. Billy Williams remembers bunking out of school on three occasions, catching a trolley bus to town and going to Phillip’s Cafe, where they could get a mixed grill and a packet of cigarettes for half a crown. This was a risky mission. He recalls that four boys were expelled when they were caught doing this, although they were later allowed back on a caution.

The daily routine began at 6am, with early-morning study for non-Catholics and Mass for Catholics at 6.30am, followed by breakfast. Lessons ran from 8am until 2.45pm, with half an hour for lunch. The afternoon was devoted to sport. Supper was served at 6.30pm, followed by more study from 7.15pm to 8.15pm, with lights out sometime between 9.15pm and 9.30pm.

Because a number of the boys came from far afield, including Mozambique, Angola, Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia), Zambia and even the Congo, it made sense that home leave was only granted once a month, so on most Saturdays, after praying the Rosary, they played sport in the morning and then went to the Wanderers or to Ellis Park to watch sport in the afternoon. Saturday nights were film nights. Sundays began with Mass, followed by breakfast and compulsory letter-writing (which was much disliked). After lunch the boys would go out for a walk. One of the most popular routes seems to have been down to the Klein Jukskei River, where they often had mud fights. The day ended with Benediction in the chapel.

School was not without its excitement. After the much-publicised murder of young “good-time girl” Bubbles Schroeder in 1949, the school was positively abuzz with all manner of rumours. Although her body had been found in Birdhaven, she had last been seen leaving Hlatikulu, the house opposite the school gates. Piet Ncwane, the school chef, who had contacts inside Hlatikulu, gave regular updates and there is a report, whether true or not, that some boys tried to turn detective and went into the property to look for evidence.

Another incident, recalled by Keith Farquharson (1952), was when some of his classmates made bombs from mining fuses and Sparklets soda siphon refills, with which they blew up the tuck shop steps. The chief culprit was apparently put on probation.

Several were nearly expelled in 1950 for conducting a sortie into Brother Florian’s room while the brothers were at Vespers, for the purpose of getting a preview of the upcoming exam papers. They were successful and returned to share their new-found information with their friends. Unfortunately, one of them left his glove in Brother Florian’s room so they were quickly identified. The owner of the glove attempted to blame Brother Florian’s fox terrier for stealing his glove, but while explaining this before the whole school, his story was undone by Brother Edwin pointing out that the glove had not been found on the floor, but underneath the exam papers. Brother Edwin eventually had a change of heart and allowed them to continue at the school, but the awards these boys had achieved were deleted from the records.

Then there were the smugglers. Keith Farquharson remembers having been quite entrepreneurial, buying cigarettes which he used to sell to the boarders for a shilling each; Boris Babaya (1950) revealed in a recent interview that he supplied his Croatian family’s homemade wine to the “Portuguese boarders” until he was caught with it in his rugby socks. Reg Titcombe (1954) describes giving four of his friends crew cuts before the 1954 annual dance. He was hauled outside, beaten and then gated for the remainder of the school year.

As this incident shows, discipline was generally strict, with liberal use of corporal punishment, as was common in boys’ schools at that time. The legendary Mrs Kempster, while much loved and respected, was well- known for using the strap in her Prep School class “two or three times a day”. Some of this may well have been forgiven by the boys due to the fact that she drove “a lovely shiny black Ford V8” and because, as Jock Loseby remembers, she was “a very disciplined and kind person”.

Mrs Kempster had joined the staff as a temporary teacher in 1943. At that time, the brothers taught all the academic subjects in the College classes, but lay teachers such as Mrs Kempster were employed to teach in the Prep School. Her past pupils recall that her classes used to win most of the prizes at the end of every year and in 1964 she became the Prep School principal, a post that she held until her retirement in 1974.

But the influence of the brothers permeated the school. While most boys have never forgotten their dexterity with the cane, they have also not forgotten that they were very approachable men and easy to talk to. In the words of one past pupil, they were “really good guys”. They were also compassionate. A number of old boys who were interviewed pointed out just how generous the brothers had been to them and to their families.

In 1941, for example, when Alf Lamberti (1951) was just nine years old, his Italian father was interned in Koffiefontein as part of the precautionary measures taken against citizens of enemy states during the war. The brothers took him in to board at Inanda free of charge. Similarly, when another boy’s family farm went bankrupt in 1957, he was kept on until he matriculated in 1960 at no further cost to the family. Another old boy attended the school from Standard 1, but his parents had very little money and the brothers let his mother pay whatever she could afford at he time. Yet another recalls how, after his parents’ divorce, the brothers stopped charging him school fees and provided all his books and uniform.

Brother Urban passed away in January 1950, at the comparatively young age of 55. He had served for six years as the principal of Marist Inanda, guiding the new school with a strong hand and a kind heart. Under his leadership, the College had grown from a prep school to a flourishing high school with double the original number of pupils and, as noted by The Maristonian of that year, he had left a particular legacy in “the magnificent cricket and football fields he laid down with infinite care and trouble; in the tennis courts and the hundreds of trees he planted”.

Brother Edwin was appointed headmaster in his place. He was a South African of Irish extraction, and was passionate about rugby. He was also “an inspiring teacher”, according to some of his former pupils to whom he taught History, Science and Mathematics. His ability to influence his pupils is exemplified by Ivor Bailey (1956), who credits Brother Edwin with turning him around academically by getting him to believe in himself.

Nevertheless, Setty Risi (1950) still remembers that many Science lessons were interrupted by Brother Edwin’s talks on rugby, during which he had shown the boys the press cuttings that described him as a future star at centre until a serious injury put paid to his promising career. It was no surprise that, despite suffering from paralysis in his neck, he grasped the opportunity to coach the boys with both hands, and turned the 1st XV into what Risi describes as “the mean machine”.

Brother Edwin was remembered especially for the relationships that he forged with the parent body through, among other things, the introduction of an annual school fête and the establishment of the Ladies' Committee.

The first fête was held in December 1950, with the intention of raising funds for the further development of the sporting facilities. Sufficient money was raised on this occasion to pay for a 200m cinder athletics track, six concrete cricket pitches, six movable grandstands, the resurfacing of two tennis courts and the acquisition of a loudspeaker system. The next fête, in 1954, raised over £2 000 that was used to build a bicycle shed that could house 500 bicycles. Today, the centre housing Design and Technology and Art stands on this site.

College fête circa 1954

When it came to fundraising, however, the greatest credit must go to the Ladies' Committee, an informal group of mothers who started working together in 1951 to raise more money for the sports facilities. Not only did they do this, they also took on a whole range of other activities, including helping at all the social functions of the College. The committee was formalised by Brother Edwin in 1954, by which time it had added two more grandstands overlooking the main oval, had paid for two more tennis courts to be resurfaced, and had built a changeroom with showers for the day boys, a concrete toolshed and a tiered embankment with concrete seats facing the oval.

The Ladies' Committee had also been providing transport for sports matches, so it was perhaps a logical step for it to decide to make acquiring a school bus the target for its fundraising in 1954. In due course “Gertie” chugged through the school gate, to the cheers of the onlookers.

Although Gertie was called a bus, strictly speaking she wasn’t really a bus. She had been bought as a green Bedford lorry for £1 600, and then had benches fitted in the back. Brother Edwin duly christened her with a bottle of lemonade. (Some reports say it was sparkling wine – whatever the case, it was suitably bubbly.)

Gertie the school bus

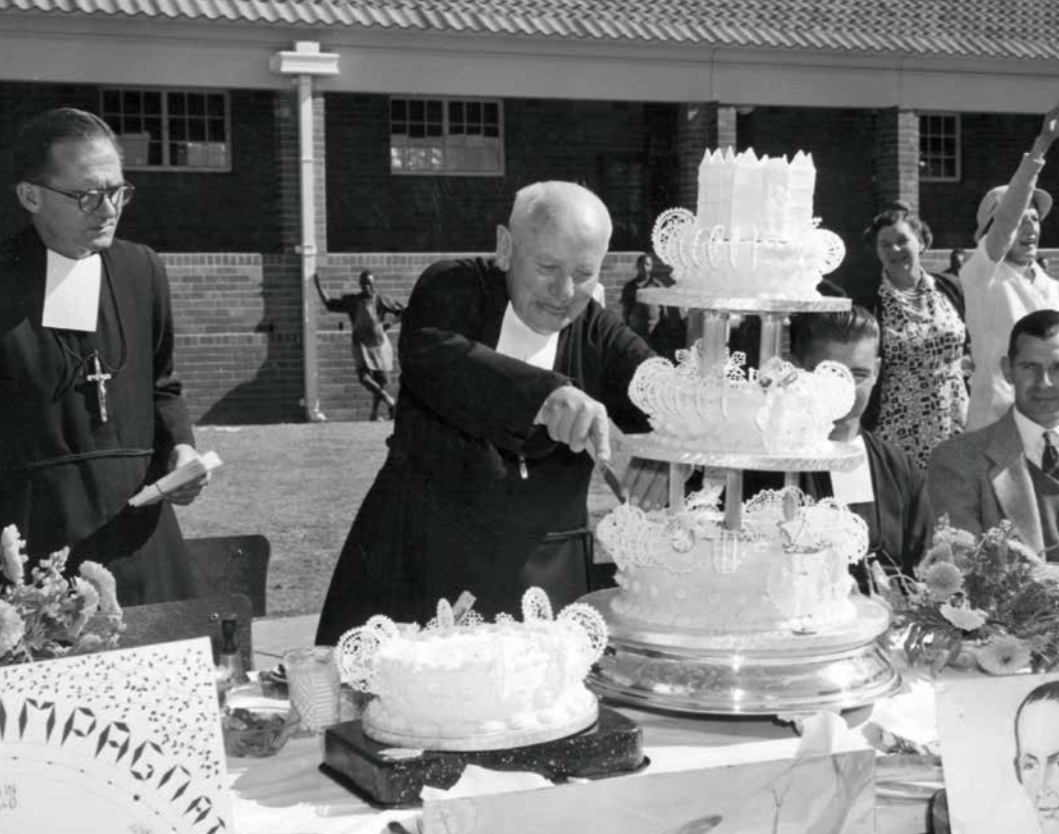

Another tour de force by the Ladies' Committee came with the beatification in 1955 of Marcellin Champagnat, founder of the Marist Brothers. After the celebration of the Pontifical High Mass in the City Hall on Monday, 6 June, which was attended by the Catholic boys from the College, the Ladies' Committee organised a feast (known at the time as the “Beatification Beano”) for all the boys on Tuesday, 7 June. And what a feast it was. They had prepared a three-course meal for 480 boys, which was served at gaily decorated tables in the quadrangle.

Beatification Beano

It was a double celebration, as it was also Brother Pius’s diamond jubilee. Now in his 77th year, Brother Pius had taken up gardening after 53 years of teaching. “Gardening,” he said, “is the purest of God’s pleasures – it’s God’s own hobby.” In his straw hat, black coat, worsted trousers and velskoens, he had transformed the bare earth of St David’s into beautiful gardens and rockeries. Many old boys from this period mention how magnificent these gardens were.

At the Champagnat celebrations he was presented with a three-tier cake, decorated with a miniature chapel and a statue of Marcellin Champagnat.

Brother Pius cuts his diamond jubilee cake

The Beatification Beano was the biggest project the Ladies' Committee had ever undertaken. With that behind them, the ladies continued with their regular work raising funds through morning markets and bridge drives, as well as supplying teas for all the sporting functions, the annual dance and the annual braaivleis.

During the seven years when Brother Edwin was the head, progress was made with the cultural side of school life. Thanks to a generous donation from Mr and Mrs WH Patley, with additional funds raised by the Ladies' Committee, work began on the school library in 1953. In 1952 and 1953, music teacher Mr Drummond Bell staged concerts at the Johannesburg City Hall, featuring a choir drawn from both St David’s and Koch Street. As the selection included works by Bach, Handel and Verdi, it was obvious that a great deal of work had gone into training the boys for the occasion.

Then, in 1954, the College’s first Gilbert and Sullivan production was staged at the Technical College Hall. After the success of this production, the team of Mr Drummond Bell and Mrs Kempster went on to produce other musicals, such as Silence in Court (1957) and The Pirates of Penzance (1958).The Prep Shool joined in the fun with annual concerts of its own, ably managed by Mrs Nora Martin and her team of teachers.

HMS Pinafore, principal actors

Of course, sport was compulsory and it is the sporting highlights that the old boys remember best. The school offered the “Big Five”: athletics, rugby, cricket, soccer and swimming. Setty Risi (1950) still remembers countless details about his rugby career as a senior at St David’s. He can name the 1st XV of 1949 and 1950, together with the position each member played (he was the scrum half), and the minute-by-minute details of the key matches.

The key fixtures for Renzo Brocco (1963) were the Marist cricket and rugby festivals, when all six Marist schools played one another. These festivals were hosted at a different school every year. St David’s hosted the first Marist schools’ cricket week in 1956. In addition to the matches themselves, the players were kept entertained with a supper and dance hosted by the Ladies' Committee.

There was a film evening, screening the recent Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand, and an outing to the Voortrekker Monument and Hartbeespoort Dam. The festival ended with a Best of the Festival XI playing a Marist Old Boys' XI. The old boys scored a convincing win.

Richard Hartdegen (1961) remembers the day in 1959 when the Inanda 1st XV finally beat Observatory in a rugby match. In those days, this was the local Marist derby and, apart from a 9-9 draw in 1956, Observatory had always had the upper hand. It was a tight match, by all accounts, with Inanda running out 8-6 winners. The following year was a bit of a let-down, however, because they were beaten 103-0 by Jeppe.

In 1954 the swimming team, which had originally joined up with Marist Observatory to compete in the annual inter-high gala, finally struck out on its own. It was too small a team to win the event, but the boys showed great spirit and determination, and did surprisingly well. At home, internal swimming galas and athletics meetings had become much-anticipated annual events.

St David’s sporting life was, however, seriously disrupted between November 1954 and March 1955 due to a serious, nationwide outbreak of polio. The government ordered that there should be no school sport at all during this period. The College rode out the crisis by organising a variety of contests and competitions, which included model making, essay writing and a talent contest held in the bicycle shed, which was won by Brian Kirchmann (1958) for playing the banjo.

In 1956, the news broke that Brother Edwin had been appointed Brother Provincial of South Africa. His loss would be sorely felt by parents and pupils alike. He was soft-spoken, with a good sense of humour, which had earned him respect. He had done much to build relationships within the school, particularly between the brothers and the parents. His leadership was firm and there was never any doubt as to who was in charge, but he welcomed the initiatives of others and this contributed significantly to building up the school. The Brother Edwin Bursary, awarded to the boy who achieved the first place in the junior certificate examinations, was created in his memory.

Brother Edwin was succeeded by an old friend of St David’s, Brother Benedict, in 1957. Brother Benedict had been in charge of the sport at Inanda some five years previously, before being appointed vice-principal at St Charles in Pietermaritzburg. Peter Owen, the first boy to win the Brother Edwin Bursary, wrote that “without shedding his dignity of office, he is ‘just one of the boys’”.

During the late 1950s it became clear that, in spite of the successes and the progress the College had made, there were some cracks appearing. The 1958 matriculation results were the worst on record: something like three-quarters of the class failed. Not surprisingly, this had a negative impact on the College. While the overall numbers were rising above 500, the senior classes were thinning out. Doug Wickins (1962) was in a class of 60 in Standard 6 (Grade 8), but there were only 17 in his matric class.

It is difficult to assess the reasons for this academic decline. Doug Wickins’ comment that he found some of the brothers very difficult to follow on account of their heavy foreign accents, may shed some light on the matter. It also seems that not all of the brothers were appropriately qualified. Then there was the matter of discipline, which seems to have deteriorated somewhat. Perhaps it also had something to do with an over-emphasis on sport. Some old boys admit that sport had been their first priority, and that their academics suffered as a result.

Thus, when Brother Anthony took over the reins as headmaster in 1960, things were due for a shake-up – and Brother Anthony was the person to do just that.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.