Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below is an excerpt from the book Falling Monuments, Reluctant Ruins: The Persistence of the Past in the Architecture of Apartheid edited by Hilton Judin. Thank you to Wits University Press for sharing it with us. Click here for more information about the book.

Book Cover

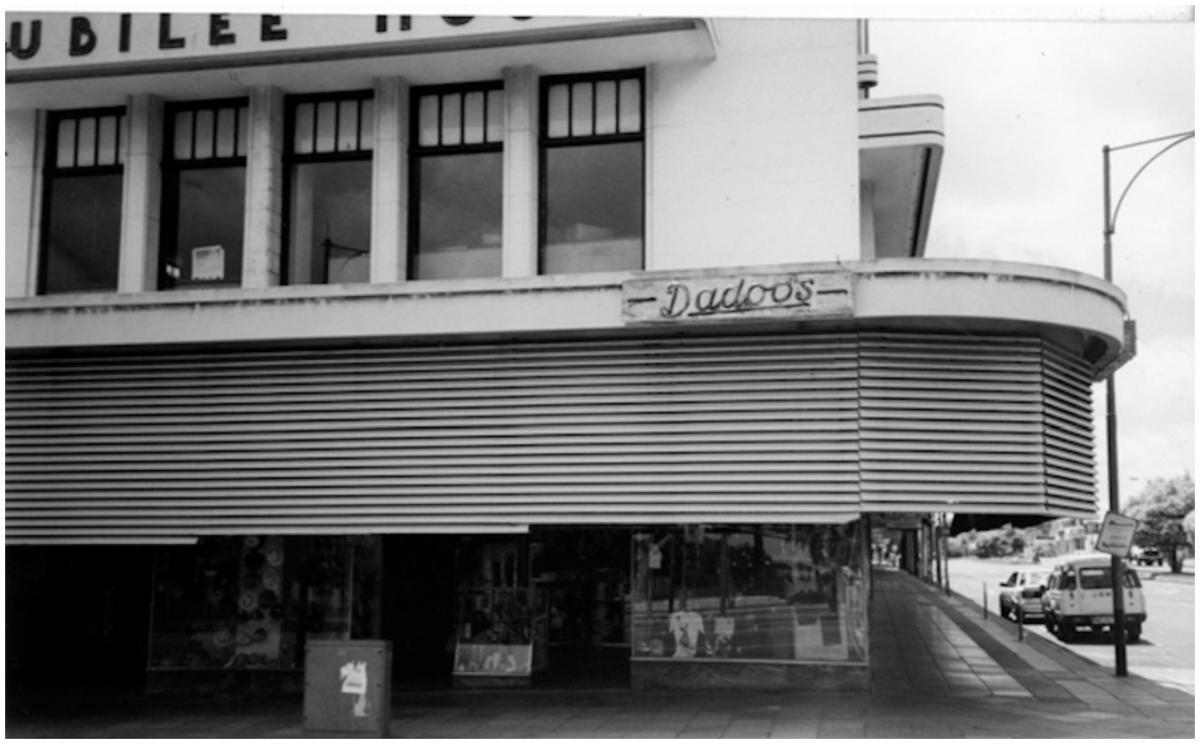

The Art Deco building standing on the corner of Market and Commissioner streets, two busy thoroughfares in Krugersdorp’s CBD, was erected by the firm Kallenbach, Kennedy & Furner, an influential architectural firm in early Johannesburg. Jubilee House, as the building was once known, originally consisted of a two storey Victorian structure built in 1898. But in 1940, this was completely overhauled and remade into the Art Deco building that still stands today. This had been the wish of its owner, M. M. Dadoo, a Muslim immigrant from Kholvad who had arrived in South Africa in the 1890s, and the father of the Communist Party and Indian Congress leader Dr Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo, born in 1909, at a time when Krugersdorp was a booming mining town.

Article published in The Star, 1940

In the early twentieth century, M. M. Dadoo was able to circumvent anti-Indian legislation that prevented Indians from owning immovable property in the Transvaal and to buy a number of stands in the Krugersdorp municipality in the name of a limited liability company. Among these properties was Jubilee House, where M.M. Dadoo opened a general dealership. Over the years, he turned the business into a sophisticated clothing retailer called Dadoo’s, importing goods from as far away as England and Japan. As the historian Charles Dugmore notes, the store attracted the custom not only of mineworkers – both black and white – in the town, but also of Boer farmers and patrons at the upper end of the market, thus competing with white shopkeepers who ‘considered whites to be their privileged clientele’. In 1919, this rivalry resulted in a landmark court case in which the Krugersdorp municipality tried to have the sale of certain municipal stands to Dadoo Ltd reversed, but failed as the Supreme Court ultimately ruled in Dadoo’s favour.

The new Jubilee House constructed in 1940 was a remarkable example of Art Deco architecture resembling an ocean liner cruising through Krugersdorp. It conveyed optimism in the fortunes of the town and the à la mode fashions to be found within the store. Constructed on the cusp of Art Deco as a popular architectural style in Johannesburg and the emerging International Style, Jubilee House’s modernity, glamour, sophistication and celebration of exuberant capitalism reflect the spirit of the age. What is remarkable about this building is the appropriation of Art Deco’s self-conscious modernity by an Indian trading family, conveying their permanency within the white town centre and economy and, by extension, that of other Indian communities in South Africa’s towns and cities.

Solly’s (formerly Jubilee House), corner of Market and Commissioner streets, Krugersdorp, 2015. (Arianna Lissoni)

Jubilee House’s architects Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner had set up a partnership in Johannesburg in 1928. Hermann Kallenbach, a Prussian-born Jewish architect who had studied in Germany, was a close friend and associate of Gandhi for over forty years. During Gandhi’s time in South Africa, the two lived together for a period under communal living arrangements, and Tolstoy farm was established with Kallenbach’s help. Kallenbach participated in the 1913 passive resistance campaign, for which he was jailed. After Gandhi’s return to India, he remained a supporter of the cause of South African Indians.

Satyagraha House, home of Gandhi and Kallenbach in Orchards (The Heritage Portal)

While it is difficult to imagine what aesthetic possessed a deeply religious Muslim Indian trader to create such an iconic structure at the cutting edge of L’Esprit Nouveau in the middle of a small town in the Transvaal, these entanglements may provide some explanation for the choice of architects. Jubilee House architecturally reflects the manifesto Zerohour issued in 1933 by ‘Le Group Transvaal,’ as Le Corbusier named the Modern Movement in the Transvaal, oozing colonial confidence in the future: ‘The contemporary spirit is abroad … we should regard ourselves as drawing near to a remote future rather than receding from a historic past - indeed all living art is the history of the future.’

In his speech at the official opening of Jubilee House in June 1940, M. M. Dadoo proclaimed his faith in modernity and a prosperous future: ‘It has been a pleasure for me… to have been in a position to erect this building in Krugersdorp, a building which we feel is in keeping with the progress of Krugersdorp and the West rand … We welcome all who care to inspect our wares and to deal with us, and I wish to assure you all that we shall continue to cater for the public of Krugersdorp as we have done in the past, with courteous and efficient service.’

The forward-looking design of Dadoo’s was not simply the appropriation of a colonial aspirational style, nor was it the subjugation to colonial rule. Instead, it embodies the determination of migrants to proclaim a prosperous future through claiming central urban space in the context of the unfolding of South Africa’s capitalist economy and segregationist state, which sought to confine Indian residential and trading spaces to racially segregated locations.

For more details on the book contact Corina van der Spoel – corina.vanderspoel@wits.ac.za or 011 717 8705

Arianna Lissoni is a researcher in the History Workshop at the University of the Witwatersrand. Her research and publications focus on the history and politics of South Africa’s liberation struggle. Her recent books include the co-edited volume New Histories of South Africa’s Apartheid Era Bantustans (2017), and Khongolose: A Short History of the ANC in the North West Province Since 1909 (2016), of which she is a co-author.

Roshan Dadoo has worked for the Department of Foreign Affairs (now DIRCO) where she served on the Middle East desk and as political counsellor at the South African Embassy in Algiers. She subsequently worked as a regional advocacy officer and director of a civil society migrant rights organisation, Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa. She obtained an MA thesis in Development Studies at Wits University in 2020. Arianna and Roshan are working on a biography of Roshan’s father, Dr Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.