Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is hard to believe that the first Portuguese shipwreck off South Africa’s east coast occurred almost half a millennium ago. This was the sinking of the large and richly laden Portuguese ship, the Sao Joao, off Port Edward in 1552. Barely two years later a second shipwreck took place, that of the Sao Bento at the Msikaba River mouth, about mid-way between Port St Johns and Port Edward.

In both instances, the survivors attempted a desperate journey on foot towards Mozambique, praying for rescue near the seasonal Portuguese trading post, at present day Maputo. Both groups of survivors closely followed the shoreline but deviated inland on various occasions to cross large rivers. Only twenty one survivors from the Sao Joao’s 500 castaways and twenty three from the Sao Bento’s 322 castaways survived these two epic journeys to Mozambique.

In contrast, the survivors of the Sao Alberto, which stranded in 1593 off Sunrise Beach, a few kilometers north of Gonubie, followed the sound counsel of Nuno Velho Perreira, former Captain of Sofala. Familiar with the narratives of the loss of the Sao Thomé, the Sao Joao and the Sao Bento, and the difficulties the survivors encountered, he wisely recommended a journey through the hinterland, instead. His sensible advice ensured two-thirds of the 285 castaways who started on this long walk to the north, survived.

The Carreira da India (India Run)

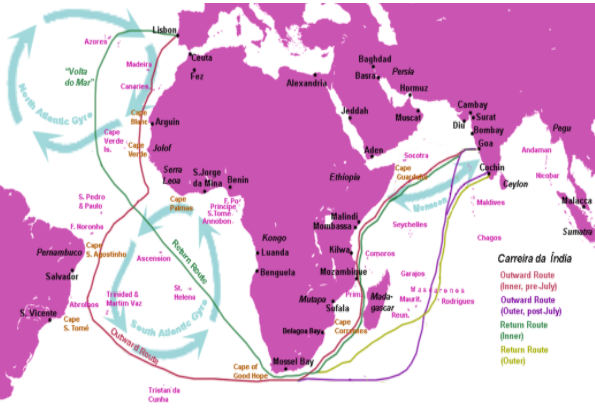

The carreira da India was the term applied by the Portuguese to describe the epic round voyage by their sailing vessels between Lisbon and Goa. Contemporaries described it as the greatest and most arduous of any in the world, possibly only rivalled by the Manilla galleon trade route across the Pacific to Acapulco. The Portugal/India round journey, including the three month stop-over at Goa to acquire trade goods, lasted about eighteen months, but only when circumstances were most favourable.

Carreira da India (via Wiki Commons)

The Southwest monsoon off the west coast of India, commenced around the beginning of June and virtually closed all harbours in this region from the end of May to the beginning of September. On the other hand, the trading season in India lasted from September to April. The Portuguese ships therefore aimed to leave Lisbon before Easter so as to round the Cape of Good Hope in time to reach the tailwind of this monsoon off the East African coast, north of the equator, which would bring them to Goa in September or October. Similarly, they aimed to depart Goa with the Northeast monsoon around Christmas, to round the Cape of Good Hope prior to the onset of the May winter season.

The ships sailing the carreira da India were mainly carracks and galleons. A Portuguese East India carrack was a large merchant ship, broad in the beam with three or four flush decks (continuous unbroken decks from stem to stern), a high poop (hindmost and highest deck of a sailing ship where it forms the roof of a cabin in the stern) and raised forecastle, but lightly gunned. Initially, of about 400 tons, they gradually increased in size to convey more trade goods on the homeward bound voyages.

A galleon, on the other hand was built longer and narrower, with less elaborate superstructures and more heavily armed.

Model of carrack (via Wiki Commons)

Some of the best and biggest Portuguese carracks were those built in India as the superiority of Indian teak over European pine, and even oak, as shipbuilding timber was recognised. A royal order of 1585, reiterated nine years later, emphasised the importance of building carracks for the carreira in India rather than in Europe because of the availability of superior timber on the subcontinent. A Lisbon built carrack seldom lasted for more than three or four round trips whereas the most famous of these India built carracks, the Cinco Chagas (Five Wounds) constructed in Goa, sailed the carreira for about twenty-five years, making nine or ten round voyages.

Experience proved ships under 500 tons were more seaworthy and economical than the unwieldy larger ones of 1 000 tons and more. The Portuguese Crown therefore decreed in 1570 that henceforth all carracks constructed for the carreira should not exceed 450 tons or less than 300 tons. This wise instruction was mostly ignored by private ship owners, agents and even the crew itself, since larger vessels overloaded with trade goods offered enormous profits back in Lisbon.

The notorious hazards of the carreira da India did not deter many people from all classes from sailing off to seek their fortunes. The carracks transported to India chiefly soldiers and fortune seekers, together with some mintage and assorted goods of little value. The ships were not particularly heavily loaded on the outward voyages, with water and wine casks often serving as ballast.

The Italian Jesuit visitor, Alexander Valignano recorded: ‘it is an astounding thing to see the facility and frequency with which the Portuguese embark for India... Each year four or five carracks leave Lisbon full of them; and many embark as if they were going no further than a league from Lisbon, taking with them only a shirt and two loaves in hand, and carrying a cheese and a jar of marmalade, without any other kind of provision’.

Professor C. R. Boxer, Camoens Professor of Portuguese, at the University of London marveled that when one considered the few and elementary navigating instruments then available, the inaccurate and small-scale charts used; the insufficient knowledge of magnetic variation and ocean currents; the complete lack of any weather forecast, the absence of a reliable nautical timepiece to calculate longitude, it was miraculous these ships reached Goa after a voyage exceeding 200 days.

Boxer also described the consequences of the chronic overcrowding and lack of elementary hygiene aboard ship. By the time the carracks reached the equator they were often floating pest-houses with their occupants dying like flies. Cooking facilities were limited to two large sand-filled boxes on either side of the main mast that could only be used during daylight hours and good weather.

Food soon became rancid or else so heavily salty it caused an unbearable thirst, that could only be satisfied in a rainstorm. The overcrowding facilitated the spread of dysentery and infectious diseases. Rats and cockroaches thrived and sometimes assumed the proportions of an Egyptian plague. It was not uncommon for three or four hundred people to die on an outward voyage consisting of perhaps six to eight hundred crew and passengers. The great majority of passengers were male and although women also went out to India, there were never more than fifteen or twenty in a carrack.

Perhaps Boxer’s description may be slightly exaggerated as there were indeed some voyages, where due to applying strict hygiene standards onboard, few or even no deaths resulted.

If overcrowding was the chief hazard on the outward voyage, overloading was that on the homeward bound. The ship’s crew were only interested in cramming in a homeward bound carrack as much cargo as she could possibly bear, to the detriment of the ship’s safety. The return cargo comprised bulky quantities of spices, especially pepper and cinnamon, saltpetre, indigo, exotic woods, furniture, porcelain, silk, and cotton. Not only were the holds filled with the spices and saltpetre, crates and packages of the other wares were piled so high on the decks, movement there was restricted by having to clamber over mounds of baggage and merchandise.

Generally, the reasons for the shipwrecks were due to shipbuilding problems, aggravated by poor maintenance, the overly large size of the vessels, persistent overloading and the lack of skilled sailors to crew these ships.

Professor Joao Almeida Flor of the University of Lisbon claimed the shipwrecks were not distributed evenly in geographical terms along the whole of the route. Instead, ship losses were concentrated, in three critical areas – in the transition from the Indian to the Atlantic Ocean, in the Mozambique Channel, and finally in the region of the Azores when closer to the Portuguese coast.

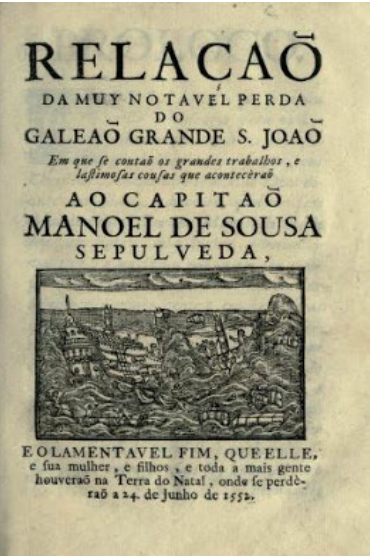

História Trágico-Marítima, or Tragic History of the Sea

The loss of the Sao Joao was initially transmitted through oral tradition. A few years later in about 1555-56, a pamphlet História da muy notável perda do galeão grande São João, was the first to be printed and went into circulation, without any indication of its author, or the date or place of its printing. Large numbers of copies were printed in each successive edition and the text functioned as a kind of introductory prototype for a series of 16th century Portuguese travel literature, composed of accounts of shipwrecks.

These narratives were originally published individually in pamphlet form and displayed hanging from strings in bookshops, hence the term literature de cordel, or string literature, applied to them. Soon out of print and probably quite flimsy, they are exceedingly rare today.

Modern example of String Literature (via Wiki Commons)

Between 1735 and 1736, a dozen of these narratives of shipwrecks and maritime disasters were published in a two-volume edition at Lisbon, by Bernardo Gomes de Brito under the title of História Trágico-Marítima, or Tragic History of the Sea.

Title page of the narrative of the loss of the Great Ship Sao Joao in the História Trágico-Marítima (via Wiki Commons)

Possibly a little later, a third volume appeared containing about half a dozen narratives of similar origin. According to Boxer, the person, or persons responsible for this third, much rarer volume, have never been identified.

Gomes de Brito’s collected editions were well received, but their literary value was not initially fully appreciated. Nowadays, some of the shipwreck narratives in the História Trágico-Marítima are considered exceptional prose in the Portuguese literary tradition.

Flor in the introduction to The Tragic Story of the Sea, commented that subsequent editions of the narrative of the loss of the Sao Joao and its principal figure Captain Manuel de Sepúlveda, were not merely dry and factual accounts, but also deliberately reflected apologetic and moralistic perspectives of Christian life and death.

According to Flor the narratives depicted Manuel de Sousa Sepúlveda as a representative of the higher echelons of the social hierarchy, endowed with military glory, material prosperity and a happy marriage to the beautiful Dona Leonor, seemingly blessed by fate. Nonetheless, the ill-starred return voyage from India resulted in a radical reversal of his status, after he had been defeated by the violence of the storm and the barbarity of the natives, finding himself completely stripped of the privileges of his rank, his riches and indeed the bare necessities for his survival. Showing signs of incipient insanity, Manuel de Sousa Sepúlveda sought a form of metaphorical death as he wandered off into the loneliness of the bush.

A symbolic reading of the loss of the São João suggests that the maritime disaster introduces a momentary interruption into the Christian theme of life as a journey, for, in the crisis of the shipwreck, the fundamental loneliness and vulnerability of the humans are brought into sharper focus.

Boxer, reviewing the narratives from more a traditional historical perspective, considered they were written with the utmost frankness, which vividly brought to life the danger and discomfort aboard a crowded and overloaded East-India carrack, sailing the carreira da India.

Narratives of shipwrecks published in De Brito’s two volumes that should be of interest to South African readers, include:

- the São João wrecked off Port Edward, in 1552;

- the São Bento wrecked off the Msikaba River mouth, in 1554;

- the Santa Maria da Barca, wrecked in the Mozambique Channel, in 1559;

- the Santiago wrecked on the Bassas da India atoll in the Mozambiquan Channel, in 1585;

- the São Thomé wrecked in Southern Mozambique, in 1589;

- the Santo Alberto wrecked off Sunrise Beach, in 1593.

Fortunately for English speakers, C. R. Boxer, translated and edited the survivor narratives of the stranding of the Sao Thome, Santo Alberto, and Sao Joao Baptista, the latter shipwrecked in 1622, possibly on Cannon Rocks near Cape Padrone. They were all published in the Hakluyt edition of 1959.

Sao Joao wreck-site at Port Edward

Although the story of her shipwreck and consequent journey of the survivors is rather well known, a summary may be useful to those not familiar with it.

The ship left Cochin on 3 February 1552, which was rather late in the season to successfully weather the stormy May season in the latitude of the Cape of Good Hope. The unfortunate delay was due to difficulties in procuring the required quantities of pepper, hampered by the outbreak of war on the Malabar Coast. Richly laden, according to George MacCall Theal, one of the most richly laden ships to have left India since the discovery of the sea route to India, with pepper and a profusion of other goods, this ‘great’ ship encountered many days of raging seas off the Cape of Good Hope. Her threadbare sails and rudder soon torn apart, captain Manuel de Sepúlveda, directed his leaking vessel towards the coast in the forlorn hope of making it to Mozambique. On the 8th of June, in sight of the Natal coastline, with the ship waterlogged and without any rudder or masts, it was carried gradually inshore, until it finally stranded just off north of the mouth of the Inhlanhlinhlu River at Port Edward. The ship split in two pieces amidships and within an hour these broke into a further four pieces. Of those on board, a hundred and ten were lost in the landing, but a hundred and eighty Portuguese and three hundred and twenty slaves survived.

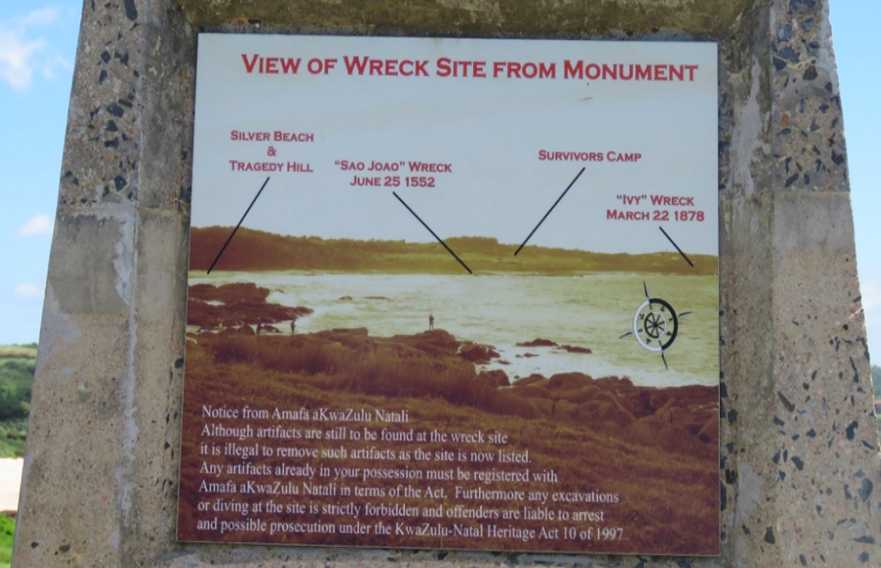

Plaque of the Sao Joao Monument indicating plausible site of the survivors’ camp (SJ de Klerk)

For many years she was considered to have been wrecked off the Mzimvubu River mouth at Port St John, hence the name given to that port.

Although five hundred crew and passengers made it ashore, one wonders whether they comprehended the great difficulties and hazards to be encountered on the gruelling foot journey to the north. The nearest Portuguese outpost was a seasonal one for ivory trading at present-day Maputo, about 600 kilometres distant.

Today, as the dense undergrowth has been cleared from our coastal beaches, it is easy to underestimate the difficulties the 16th and 17th century shipwreck survivors encountered on their desperate coastal walks to Mozambique. Professor Kirby in his Source book on the Wreck of the Grosvenor, confirmed that the going for half-starved and barefooted castaways of nearly five centuries ago, was incomparably harder than for a fit and well shod person today.

Although the survivors initially planned to use timber from the wreck to build a small caravel to sail to Mozambique, the rough seas had destroyed all the ship’s timber.

After waiting for twelve days for the injured to recover and to salvage useful items washed up on the shoreline, the survivors set out for Maputo on 7 July 1552. Staggering along the shoreline, with numerous tiring inland detours to cross large and deep rivers such as the Umzimkulu, three hundred emaciated and exhausted survivors arrived at the southern shore of Maputo Bay, about three months later. Here, a friendly local African chieftain named Inyaka, provided some food and comfort. He recommended they await the arrival of the annual Portuguese ivory trading vessel, rather than venturing further north, into territory where tribesmen were antagonistic towards the Portuguese. Confused and uncertain whether they had reached Delagoa Bay, the survivors insisted on trekking further north only to be systematically robbed of all their belongings by the hostile Africans. Dona Leonor, wife of the Captain De Sepúlveda, stripped of all her clothing and deeply ashamed, dug a hole in the sand and buried herself waist deep using only her hair to cover her modesty. The pilot, André Vàs, and the others were forced to leave the Captain and his wife behind and carry on with their journey. De Sepúlveda was reduced to foraging for fruit in the thicket to try and sustain his family. Dona Leonor, her two children and several slaves died shortly thereafter from hunger and exhaustion. The bereaved Manuel de Sepúlveda distraughtly wandered into the thicket never to be seen again.

The few remaining survivors were fortunate to be rescued by a passing Portuguese vessel after being ransomed from the natives for some beads. Fortunately for posterity, a certain Álvaro Fernandes, a storekeeper on the Sao Joao survived to tell the sad narrative of the loss of this ship and the many tribulations of its survivors.

In an interesting and informative article for the Annals of the Natal Museum, dated December 1984, Tim Maggs explained for some years prior, the Archaeology Department of the Natal Museum had been tracking down and recording ceramic fragments and carnelian beads collected on the south coast of Natal, in the vicinity of Port Edward. Carnelian beads are translucent, semi-precious agate, red or orange in colour. They are significant because they are associated with 16th and 17th century Portuguese wrecks on their homeward bound voyages from India to Portugal and have been found at some South African wreck sites. Following Vasco da Gama’s voyage in 1498 the Portuguese entered the Arab dominated trade, but the beads were also shipped back home to Portugal, therefore are only found on homeward bound shipwrecks.

He added that although the ceramics were much less common and more fragmented than those recovered from the Msikaba river wreck, there was sufficient evidence to demonstrate a very close stylistic similarity between the two. Maggs and fellow archaeologist C. Auret, established in 1982 that the Msikaba river wreck was that of the Sao Bento, which foundered there in 1554. Since no other wreck site on the south-east African coastline had to Maggs’ knowledge produced similar porcelain, all being of styles datable to the late sixteenth century or later, these appeared to be the only two mid-sixteenth century wrecks in the region.

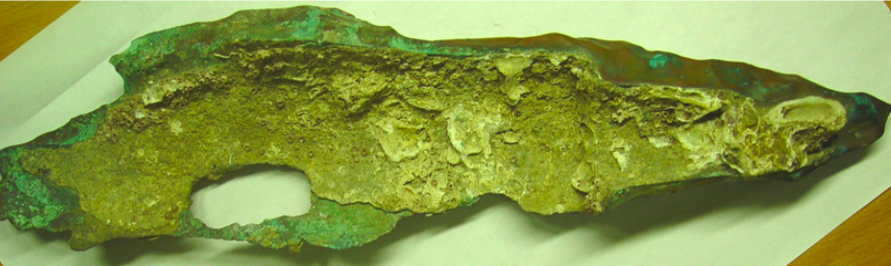

Fragment of bronze cannon discovered by L. Harris off Port Edward (Via Wiki Commons)

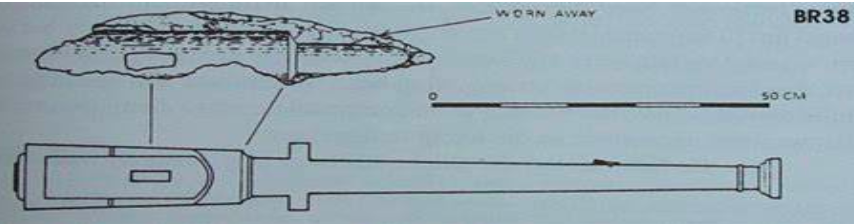

Diving on the Port Edward site in 1980, Natal diver L. Harris produced further evidence in the form of a fragment of a bronze cannon, so badly scoured by the sea and sand that only a fraction of the breech has survived. The weight of a brass cannon would have prevented it from being moved any significant distance by the sea current. It could therefore only have originated from the nearby wreck of an early sailing ship.

Illustration in the article by Tim Maggs indicating the similarity of the above bronze artefact to a breech-loading falconet (via Wiki Commons)

According to Maggs, the surviving portion of the cannon was only 60 cm long but there was sufficient detail to identify it as part of the breech of a falconet or breech-loading swivel-gun with a barrel diameter of 6 cm at the breech. It was very similar to falconets from the Sao Bento and from the Santiago wrecked in 1585, the only examples available to him for comparison.

He found an important dating aid to be the Taoist tri-gram motif on shards of porcelain found in rock crevices below the highwater mark, since Taoism was particularly influential during the reign of the Emperor Jiajing 1522-1566.

His article concluded that while the narrative of the loss of the Sao Joao was not as precise as that of the Sao Bento, the evidence presented clearly linked the Sao Joao to the Port Edward wreck-site. The dating of the ceramics agreed, as did the given latitude of the wreck and, in general terms, the description of the wreck-site.

A recent visit to Port Edward confirmed that the monument to the Sao Joao, on the waterfront with informative plaques attached to its four sides, still appeared in good condition. The plaques provide interesting information on the sinking of the ship, the likely site of the survivor camp and the harrowing walk to Maputo and beyond.

The beach just north of Port Edward seems about the only spot where the shipwrecked could safely have reached land, since the coastline both north and south appears very rocky.

The question of the whereabouts of the survivor campsite was considered in some detail by Elizabeth Burger in her 2003 dissertation for the Master of Arts degree.

Based on the statement in the survivor account that 500 hundred people encamped in the area following the wrecking, Burger calculated that the size of this camp must have encompassed an acre, and possibly even greater. The narrative merely described the camp site was close to the wreck, fresh water was available and that two hills were visible from it.

According to Burger, an inspection of the geological survey of South Africa, aerial photographs, the 1:50 000 map and excavations in the area revealed only two perennial rivers found within easy walking distance of the wreck-site, the Inhlanhlinhlu and the Kuboboyi.

Burger identified three possible sites where the survivor camp might have been sited.

The most plausible one would have been on Keiser’s Farm, indicated in the image below. It was situated near to the wreck and fresh water would have been available from the Inhlanhlinhlu and Kuboboyi Rivers, as well as a stream running through the farm. The area is relatively flat and somewhat sheltered by the surrounding low hills.

Recent photo of same area. The middle/right hand foreground (Keiser’s Farm) occupied by three buildings, may have been the survivors’ camp site (SJ de Klerk)

Another possibility would have been at the so-called Tragedy Hill, behind the main Port Edward Beach, although Burger argued that heavy undergrowth would have made it virtually impossible for 500 people to encamp here.

The last possible site, not quite visible from Port Edward, could have been on the southern bank, slightly upstream from the Kuboboyi River mouth.

Tragedy Hill next to the Port Edward Beach with the lagoon of the Inhlanhlinhlu River behind it (SJ de Klerk)

The general area of the Sao Joao wreck site is very accessible and remains an interesting outing for visitors to the South Coast of KZN. Visitors should however exercise caution when carrying expensive cameras and like equipment when visiting some of the more isolated sites.

I wish to thank Tim Maggs for kindly emailing me a copy of his article on locating the wreck-site of the Sao Joao and his helpful comments.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Axelson, E. Portuguese in South-East Africa 1488-1600. Johannesburg, 1973.

- Boxer, C.R. The Tragic History of The Sea, 1589-1622. Cambridge, 1959.

- Boxer, C.R. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire 1415-1825. Lisbon, 1991.

- Burger E. Reinvestigating the Wreck of the Sixteenth Century Portuguese Galleon São João: A Historical Archaeological Perspective. Dissertation for MA Degree, University of Pretoria. 2003.

- De Kock, W.J. Portugese Ontdekkers om die Kaap. Die Europese Aanraking met Suidelike Afrika 1415-1600. Kaapstad, 1957.

- Flor J. A. A Tragic Story of the Sea. Volume 6. Translated by John Elliot. Portugal. 2008.

- Mackeurtan G. The Cradle Days of Natal. Durban. 1972.

- Maggs, T. The Great Galleon São João: remains from a mid-sixteenth century wreck on the Natal South Coast. Annals of the Natal Museum. 26(1)1984, pp. 173-186.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.