Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This last week brought a spectacular media scoop to Steve Humphrey of the BBC when an anonymous tip off (presumably telephonic) led him to a bell shaped parcel left at the entrance to the Swanage Pier in Dorset, England. The BBC team was on hand to film the careful unwrapping of the parcel to reveal a ship's bell with the word “Mendi” deeply etched in capital letters on the side (main image from Steve Humphrey and BBC TV South). The bell of the SS Mendi, lost in World War 1, had been found.

Mendi Bell (BBC)

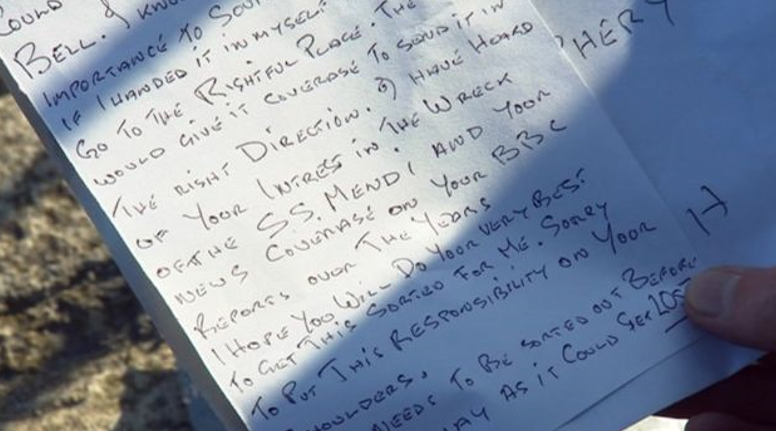

Attached to the parcel was an envelope, addressed to Humphrey, containing an unsigned letter giving him the responsibility to do “the right thing” and ensure the bell finds an appropriate home. Humphrey reported that he had been looking for the bell of the Mendi for the last 30 years, so its return was an emotional and significant moment. Our congratulations to the BBC on a wonderful piece that is far more than a regional news story.

The anonymous letter (BBC)

The news was immediately picked up by The Argus (click here to view) and word spread across South Africa. I learnt about the find because I received a breaking news flash in an email having attended the UCT commemorative conference in March this year.

An exciting find but why anonymous?

The story of the return of the bell strikes me as somewhat peculiar. It is a strange letter, something of a confession and redemption of a troubled conscience. An anonymous person wishes to return an item that he clearly considers belongs elsewhere before departing this life. The writing on the letter is in capitalized not cursive script, further pushing anonymity. Why did the possessor of the bell of the Mendi not walk into a local museum, announce himself and hand over his bell and explain how and why and he came of it? Many enthusiasts will be craving answers to these questions.

An important relic and some deeper questions

We would like to know something about what the experts in art and antiques call the provenance of the item. The ship’s bell is perhaps the most significant artefact of the Mendi. Its find is rightly celebrated. It is extraordinary when the search has been on for at least four decades. According to John Gribble, the archaeologist who has researched the Mendi, the bell “looks right” for its time, material and size.

2017 is the centenary year of the tragedy of the sinking of the Mendi and it is particularly significant that the bell should be “found“ in this commemorative year. However, the return of the Mendi’s bell raises all sorts of questions about salvage, the morality and legality of removing objects from wrecks, the legal points about ownership and diving rights, what happens to artefacts when a wreck is declared an official war grave and what happens to salvage taken before the declaration of a war grave.

When was the bell removed from the Mendi?

The Wessex Archaeology Desk based assessment of the Mendi, commissioned by English Heritage in 2007, mentioned the bell’s existence and noted that “according to Admiral Söderland (SA Navy retired) the bell of the Mendi is reported to be in a pub somewhere on the south coast”, but there was no verification of this assertion. The salvage of the bell was simply a rumour without confirmation (see pg 70 of the Wessex report). Söderland’s story would fit with the rediscovery of the Mendi bell in Swanage. The bell could have been removed any time between 1974 and 2007 but, as a highly desirable object, it is more likely to have been taken by a diver fairly early after the identification of the wreck.

The South African connection

Of course South Africans have a particular interest in the Mendi and its bell because the tragedy of the Mendi was South Africa’s worst maritime disaster of the 20th Century. We honour the men who lost their lives in heroic circumstances as the Mendi sank in the icy waters of the English Channel. The stirring speech attributed to the Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha has passed into proud myth. The South African Order of the Mendi awarded for heroism recalls the tragedy and the heroism of South Africa’s black labouring soldiers who went to a watery grave. As mentioned, 2017 marks the centenary and there have been commemorations in Britain, France and South Africa. We have remembered the men of the Mendi in wreath laying ceremonies, in the refurbishing of old memorials and the installation of new ones.

The Story of the Mendi

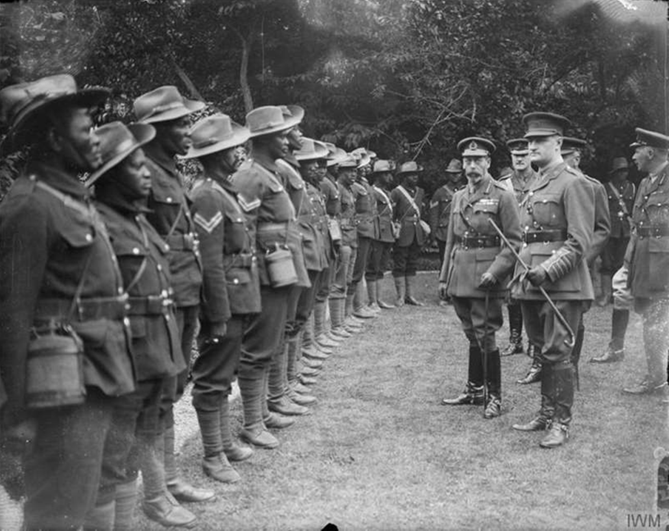

When the SS Mendi went down there were 824 men on board. The official death toll amounted to 646 men (607 black men of the South African Native Labour Corps, 5th battalion two of their officers and 7 non-commissioned officers; and 30 crew members). There were 267 survivors. The SANLC comprised men who had been recruited throughout South Africa to serve as workers and labourers on war fronts but not as armed soldiers, as black men were not permitted to carry arms and could not become fighting soldiers. These men were nonetheless volunteers who signed year length contracts to serve the British Empire and swore allegiance to King George V. The men of the Mendi were the last contingent of the SANLC to be conveyed to France.

George V inspecting South African Native Labour Corps members in France (Imperial War Museum)

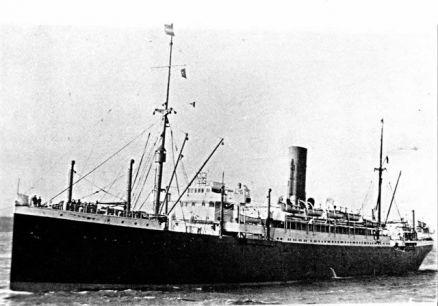

The tragic sinking of the Mendi occurred on the final leg of the journey as the ship set sail from Portsmouth to Le Havre. In the early morning on February 21st 1917, 11.3 nautical miles south to southwest of Catherine’s Point on the Isle of Wight, the SS Darro - a much larger cargo ship - sliced into the side of the Mendi in dense fog causing the lower decks to fill with water. The Mendi sank in 20 to 30 minutes. Most of the men drowned as they could not swim, the water was freezing and there were insufficient life boats. The Darro did not stop to collect survivors although the escorting destroyer the HMS Brisk tried to rescue men in the water.

SS Darro (South African Museum of Military History)

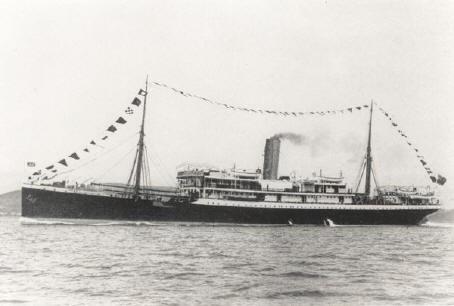

SS Mendi (Wikipedia)

Prior to 1916, the SS Mendi was a commercial cargo cum passenger ship, that carried goods between England and the West Coast of Africa. The Mendi was a single screw steamship built in the early 20th century at Linthouse Glasgow by the shipbuilding firm of Alexander Stephen and Sons. It had a gross registered tonnage of 4229.53 tons. It was owned by the British and African Steam Navigation Company. In 1916 it was commissioned by the British military to be refitted as a troop carrier.

The Port Elizabeth Connection - the 24th Bell a 2017 memorial of the Mendi

Port Elizabeth has an unusual recent connection to the bell of the Mendi. The most fitting remembrance of the men of the Mendi has been the addition of a memorial bell (plus another from the citizens of Nelson Mandela Bay) to the carillon of the restored 23 bells of the Port Elizabeth campanile, making 25 bells in total. The Campanile is a commemorative bell tower that stands 170 feet high in the Port Elizabeth Harbour. It was erected in 1923 and honours the arrival of the 1820 Settlers at Algoa Bay. Today this simple brick tower in Florentine style (the design of architect William John McWilliams (1873-1950) of the firm Jones and McWilliams) is somewhat dwarfed by the Settler Freeway. A clock was installed in 1925 with bells added in July 1936 following a fund raising drive by the citizens of Port Elizabeth. The carillon of bells was manufactured by Gillett and Johnson, clock makers and bell founders of Croydon, Surrey, England. The 23 bells with a gross weight of 16 tons, honoured King George VI whose silver jubilee fell in that year.

In 2015 the Nelson Mandela Development Agency appointed Ibhayi Contracting to refurbish the Campanile and the Port Elizabeth municipality commissioned the casting of another two bells, one to honour the men lost on the Mendi. Gillett and Johnson (though note this is a successor firm and inheritor of the name) was again commissioned to cast the new bells. In 2017 the new carillon pealed to remember a more inclusive history and war time sacrifice.

Campanile Port Elizabeth (The Heritage Portal)

The Wreck of the Mendi and the Salvage of Artefacts.

The wreck was first located in 1945, but it was only positively identified by Martin Woodward in 1974 when he found, not the bell, but a ceramic plate bearing the blue crest of the British and African Steam Navigation Company, the original owner of the SS Mendi in its prior life as a cargo and passenger ship that plied its trade between Britain and West Africa. Woodward founded the Arreton Shipwreck Centre (formerly the Bembridge Maritime Museum) on the Isle of Wight in 1978. This museum displays a number of objects retrieved from the Mendi by Woodward during his dives. Visitors can view the brass bridge telegraph, a porthole, a wheel boss, engine parts, a brass saloon window amongst other objects. It is believed that all of the artefacts recovered from the site by Martin Woodward have been reported to the Receiver of Wreck.

The Mendi as a “Sainsbury’s“ for the recreational divers 1974 to 2007

Other divers it would seem were far less scrupulous than Woodward. Following its identification, the Mendi wreck became a recreational dive site and the location was included in various wreck catalogues and dive guides to the South coast of England. No human remains have been recovered. It is evident from the Wessex Archaeology Desk based assessment of 2007 that divers removed many items while searching for valuable non-ferrous metals and souvenirs in the 1980s and 1990s. The wreck was even known as “Sainsburys” because divers were able to fill their bags with artefacts. The Wessex report comes to the conclusion that there has been under reporting to the Receiver of Wrecks, but an appendix attempts to document finds before and after 1993.

Contemporary photograph of the men on board the Mendi (Imperial War Museum)

The Mendi as an Official War Grave

The comprehensive Wessex Archaeology report argued the case for the declaration of the Mendi site as an official war grave. This happened in 2009 resulting in the Mendi receiving added protection. The removal of objects from the site is now prohibited. A puzzling aspect is that the ownership of the wreck of the Mendi, at the time of the report (pg 55), appears to be unclear.

Significance of a Ship’s Bell

The bell symbolises the soul of a ship. When a ship sinks it is perhaps the most desired and desirable of objects to be recovered from the wreck. If a ship is broken up it will be a prized item to be saved. It may often be the only positive means of identification in a shipwreck. The ship’s bell has a long history and in days before modern clocks and accurate time keeping, the bell , together with a timer was used to indicate time on board and to regulate the sailors’ watches. Eight bells marks the four hour watch with one for each half hour of the watch. The bell is usually made of brass or bronze and will be engraved with the name of the ship. It has to be accessible on deck with a rope attached to the clapper. A bell would also be used for safety in foggy conditions. However, by the time of the 1917 voyages, whistles were used and from the report of the Board of Trade, whistles were sounded by the Mendi (rather than the bell) to signal the imminent danger in conditions of fog and low visibility.

What is the next step?

The ownership of the wreck of the Mendi appears to be in doubt (see discussion in the Wessex Archaeology report). It is a complex matter, but a century later there is a strong case for South African interests to prevail. This year the South African ceremonies to commemorate the Mendi included a wreath laying by descendants at sea at the site of the wreck. The return of the bell of the Mendi, must surely move beyond a news scoop to inspire and energise the South African Heritage Resources Agency to negotiate the return of the bell to South Africa where it surely belongs. In terms of a final resting place... perhaps the Port Elizabeth Campanile?

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.

References and further reading

- Norman Clothier. Black Valour. University of Natal Press. 1987

- Albert Grundlingh. Fighting their Own War: South African Blacks and the First World War. Ravan Press. 1987

- Albert Grundlingh. 2014 War and Society Participation and Remembrance South African Black and Coloured Troops in the First World War 1914-1918. Sun Press. 2014

- Nick Ward. Troopship Mendi: The Black Titanic. Nick Ward Publications, 2016

- South African Delville Wood Commemorative Museum Trust in February 2017 produced the Centenary Retrospective the Sinking of the Mendi 1917 - 2017 . This has the Mendi roll of Honour and also v usefully the names of everyone buried at Arques la Bataille.

- John Gribble and Graham Scott . We Die Like Brothers , the Sinking of the Mendi. Historic England. 2017

- Ibhayi, A Century Later the Bells will Chime A Memorial to SS Mendi, 2017

- Wessex Archaeology, SS Mendi, Desk based Assessment, report 2007

- Willan, BP, "The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918", in The Journal of African History, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1978, pp. 72-73

- Board of Trade Report 39085a "The Mendi and the Darro", 1917

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.