Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Pre-1930s, the art of photography in South Africa was a Eurocentric affair. While the South African Black population may have been photographed extensively (more so from an Ethno-photographic angle), little, if anything, has been recorded on professional studio photographers of colour during this era.

In my previous articles on the history of South African photography, I have reflected that pre-1920 South African-based photographers were all white, resulting in these articles having mostly a Eurocentric flair.

This brings me to a crucially important question on South African photographic history.

Is it possible that South-African citizens of colour only started considering photography as a profession post the 1920s, some seventy years after the first commercial photographer, the Frenchman, Jules Léger, arrived in South Africa (1846)?

My hypothesis - unlikely. The challenge remains to find the evidence for this hypothesis. The primary source for such evidence resides in obtaining original photographs captured by photographers of colour as these early original images may contain the details of the actual photographer.

The Indian population (as well as Chinese) was brought into the country as indentured labour at the turn of the 1900s, explaining part of the reason why they possibly would only have set themselves up as studio photographers a few years down the line. But what about the African Black and Coloured population?

For the benefit of the international reader, in South Africa reference is made to the White, African Black, Indian, and Coloured (or brown community), where the latter three are also referred to as Black South African citizens. A black person or person of “colour” would fall into the last three categories.

The Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (which has primarily focused on the period before 1915), contains several photographs of people of colour, yet until recently did not have a professional photographer of colour recorded, even for the period 1920 to 1930.

There was big excitement when the collection obtained a photograph (circa early to mid-1920s) containing the name AR Munshi. At first, I made nothing of the name, only later to register that this is a surname that originates from India.

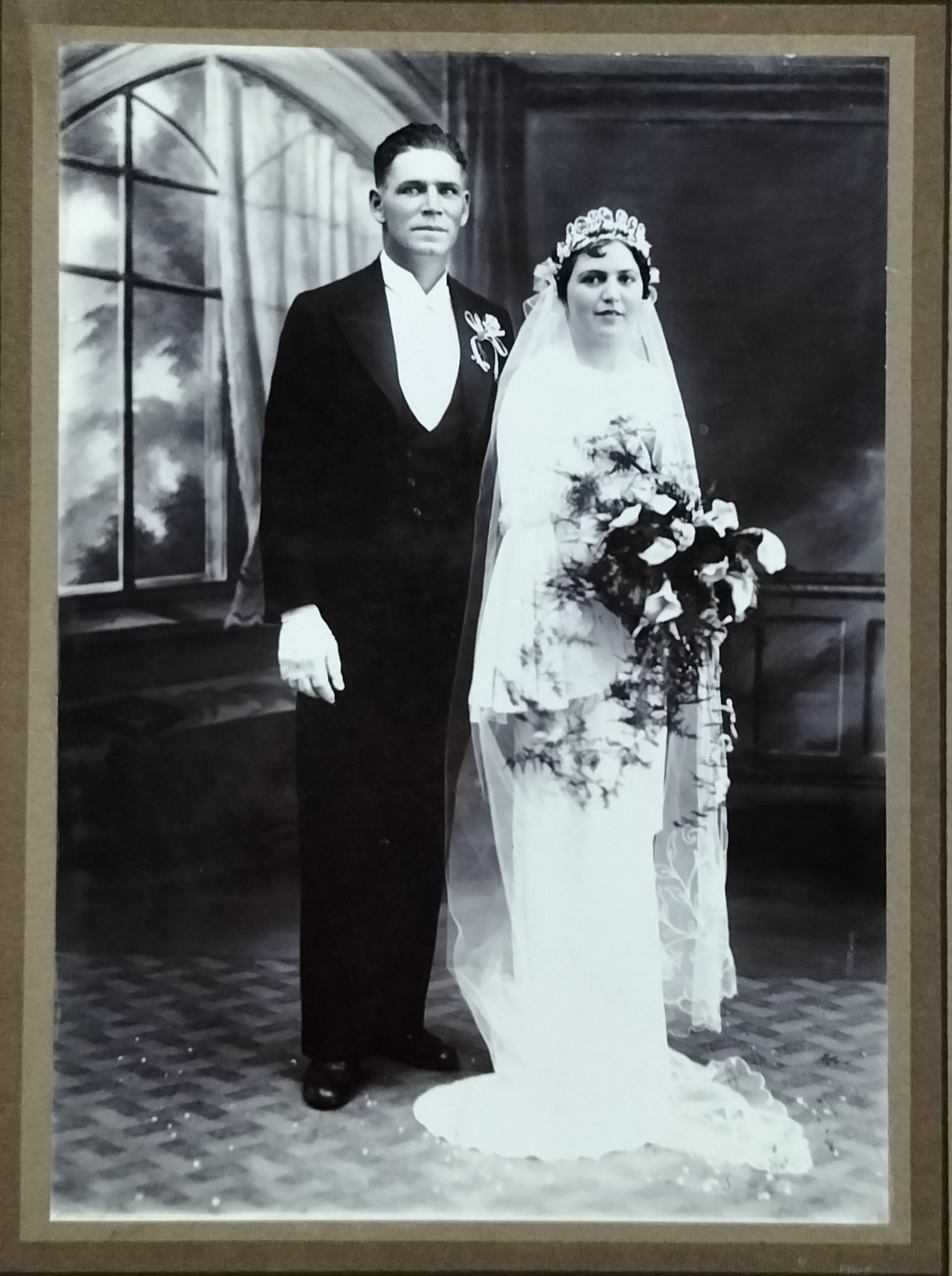

Abdul Rahim Munshi had his studio at 302 Main Road, Fordsburg (circa 1920s). This single larger format photograph, of an unknown white couple on their wedding day, is of excellent quality. Munshi clearly invested money in setting up his studio professionally as the backdrop he used is of high quality.

Munshi did not use pre-printed card stock to paste his photographs on. Instead, he applied a rubber stamp on the back of the card-mounted photograph containing his name and address indicating that he was the photographer.

Fordsburg, between the period 1900 and 1930, had at least nine other professional photographers, all of them white. The remote possibility that Munshi rented a studio from one of these photographers cannot be ignored as it was not an uncommon practice amongst photographers to do so. I do, however, not favour such a possibility.

It is also not known where Munshi developed his skills as a photographer. Did he arrive in South Africa having built up experience in British Colonial India or did he perform as a studio assistant for one of South Africa’s white photographers before he went on his own?

The assumption is further made that Munshi would not have arrived as an indentured labourer, but instead that he landed in South Africa as a merchant, or possibly the teenage child of a merchant.

An unknown couple photographed on their wedding day by the Fordsburg-based photographer AR Munshi

A brief history of Fordsburg

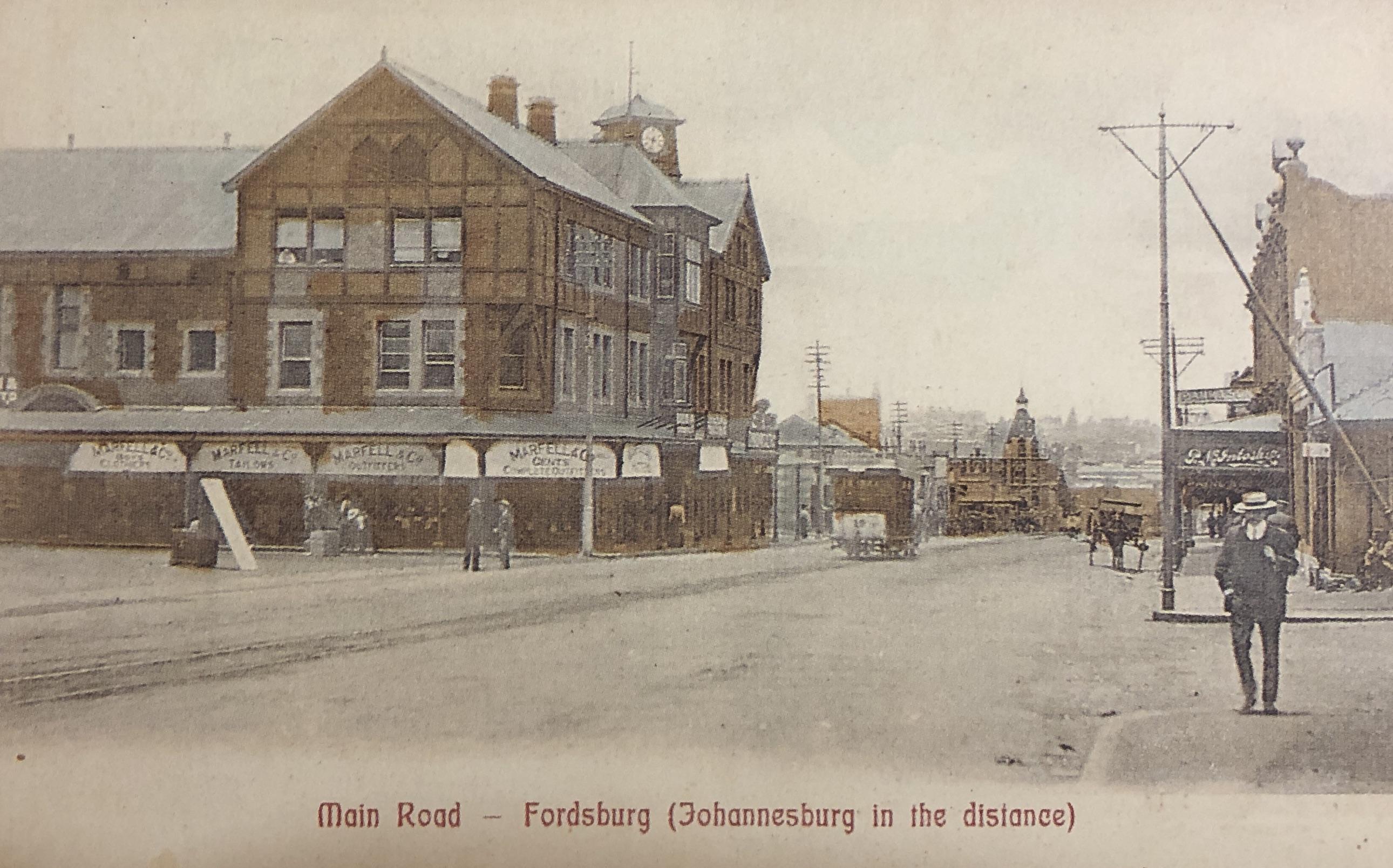

Fordsburg was established in 1888 on land that formed part of the farm Langlaagte. The multi-ethnic suburb, with a fascinating and turbulent history, was built on the outskirts of the Johannesburg gold reef to house mainly miners.

It was named after Lewis Peter Ford of the Jeppe and Ford Estate Company. Ford was once the Attorney General of the Transvaal under Sir Theophilus Shepstone’s administration.

Due to the proximity of the Robinson, Crown, and City Deep mines, Fordsburg became a popular working-class suburb for miners. Indian and Chinese traders set up businesses in the area and often lived on the premises as Fordsburg leases at the time allowed stands to be used for business and residential purposes.

Fordsburg was also the site of the miners’ strike in 1922, known as the Rand Rebellion. Mine bosses insisted on using African labour in the mines. White workers opposed this policy, and Smuts had to call in the troops and air force to contain the strike.

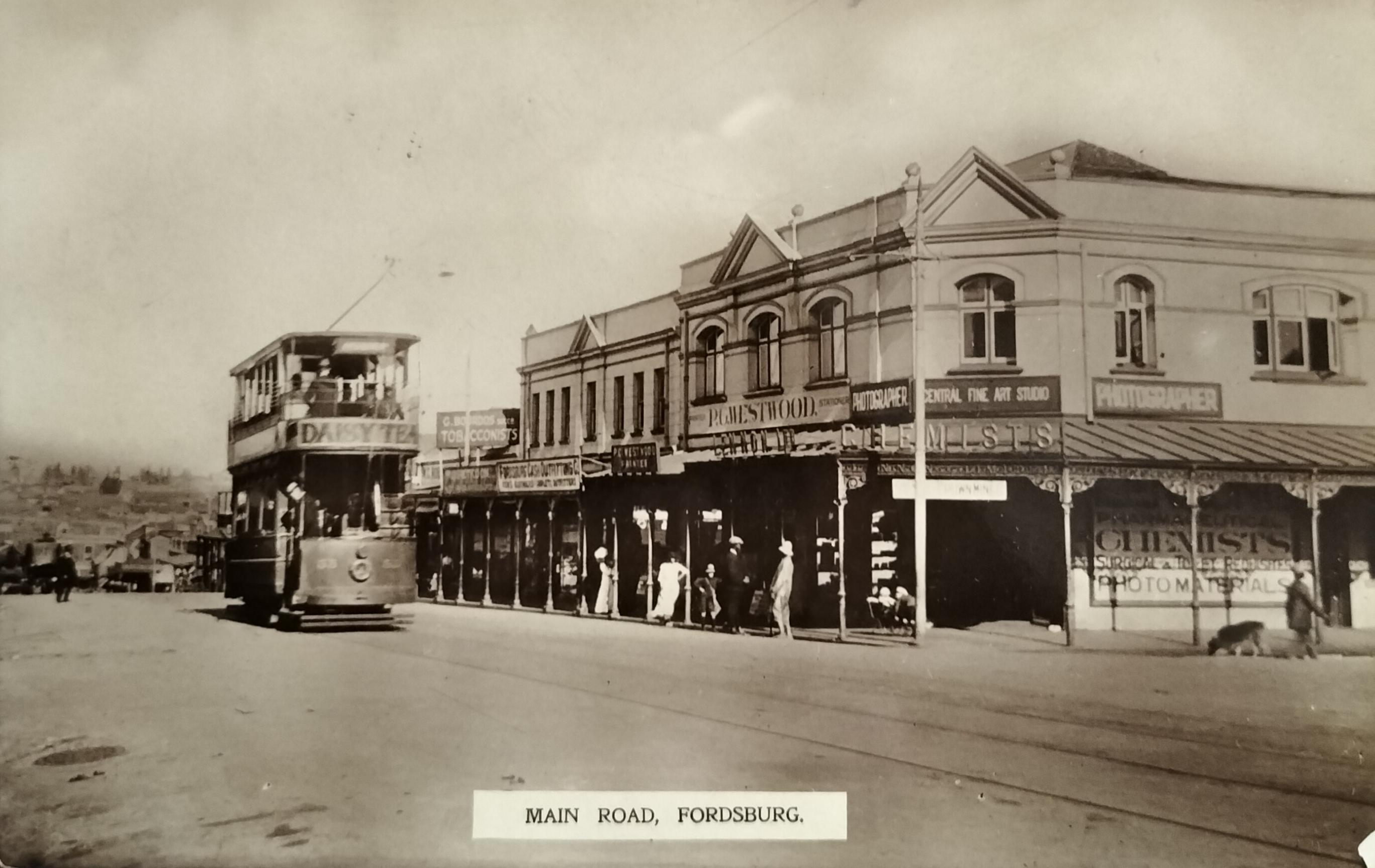

Fordsburg - Main Street showing the chemist and photographic establishment "Fine Art Studio" circa 1915. This same studio was manned by the photographers Murton and Kinsman during the early 1900s.

Fordsburg - Main Street (circa 1905) where AR Munshi eventually established himself as a studio photographer

A brief history of Indians in South Africa

The South African Indian population is a heterogeneous community distinguished by different origins, languages, and religious beliefs. During the Dutch colonial era, the first Indians arrived as slaves as early as 1684. In the period 1690 to 1725, more than 80% of the slaves were Indian. This practice continued until the end of slavery in 1838.

After the British colonised South Africa in the 1800s, Indian people were again brought from their home country (which was also colonised by Britain at the time) to work as indentured labour on the local sugar cane fields, railways, and mines of colonial Natal (now known as the province of KwaZulu-Natal) between 1860 and 1911.

During the time of indenture, Indian and Arabian merchants also arrived in South Africa to set up trading posts, further expanding the community. This resulted in parts of the cities of Durban and Johannesburg becoming thriving Indian neighbourhoods in the later years of the 19th century. The growing community of workers was catered to by the first Indian merchant stores that opened in Durban in 1872, selling spices and other necessities. The indentured Indians, normally indentured for 5 years, had the intensive task of cultivating, growing, and harvesting the sugar cane.

After their period of work ended, the contract of indenture offered workers the option of returning to India or accepting a plot of land. History suggests that a small number opted to return to their home country, while most Indian workers accepted the land offer to start their own ventures.

During the 1900s, the Indian community did not shy away from political activism and rose against the prejudice and extreme legislation they were facing.

Today, many South African Indians can trace their heritage back to these workers, who mainly arrived from the Indian ports of Madras and Calcutta.

Origin of the surname Munshi

Munshi is a Persian word derived from Arabic that is used as a respected title for persons who achieved mastery over languages, especially on the Indian subcontinent. It became a surname to those whose ancestors had received this title - some also served as ministers and administrators in the kingdoms of various royalty and are regarded as nobility. The family name Munshi was adopted by South Asian families (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh). In modern Persian, this word is also used to address administrators and heads of departments.

Closing

To date, it has not been officially recorded who the first professional South African photographer of colour was.

The Munshi image dating from the early- to mid-1920s is a good starting point. Unfortunately, I have not been able to collate much biographical information on AR Munshi. Of interest is his date of birth and death, where he was born, and when he arrived in South Africa. The only record found is of his daughter, Sakina, who passed away on 29 April 1936 at the age of 18 months. The address on the death certificate is that of 302 Main Street, Fordsburg, the same address where Munshi had his studio.

I hope this brief article will trigger possible additional input from family or fellow researchers resulting in a more detailed reflection on Munshi’s life story.

It must be emphasised here that the focus is on Professional Studio Photographers.

I fully acknowledge that there may well have been earlier photographers of colour who may have operated, amongst others, as street photographers, mining compound photographers, or enthusiastic amateur photographers within communities. Although also of interest, these types of photographers have been excluded from the research list as it is nearly impossible to identify them.

Identifying South-African photographers of colour before the 1930s would make for an outstanding research topic. It remains my hypothesis that it is highly probable that there would have been several earlier photographers of colour active in South Africa before the 1930s, but that they did not apply their names on photographs produced by them making identification of photographers near impossible.

The African Black photographer, Santu Mofokeng (1956-2020), has one African Black studio photographer recorded, namely Ventersdorp-based A.M. Makhubu dating from 1927 (Mofokeng, 2013). The remainder of the photographs in this publication are of Black South African sitters by either white photographers or unknown photographers.

Until proven otherwise, Makhubu is also accepted as the first South African Black studio photographer. In the interim, I believe Munshi was the first professional photographer of colour in South Africa followed by Makhubu.

Researching professional photographers is not exclusive of Chinese photographers who may have been active in South Africa before 1930.

I will be elated if my hypothesis that no Black (African, Coloured, or Indian) commercial photographers practiced the art of photography between 1846 and 1920 is proven wrong.

Main image: Rubber stamp applied by the Fordsburg-based Indian photographer on the back of a Cabinet Card photograph (see wedding photograph above). Many photographers of that era ordered pre-printed card stock from Europe to paste their photographs on. Applying a rubber stamp on card stock was a cheaper option for the photographer .

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Bull, M. & Denfield, J. (1970). Secure the Shadow – The story of Cape Photography from its beginnings to the end of 1870. McNally. Cape Town

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection (Munshi photograph)

- Latilla, M. (2019). Suburb by suburb research – History of Fordsburg (https://johannesburg1912.com)

- Mofokeng, S. (2013). The Black Photo Album / Look at me (1890 – 1950). Steidl. Göttingen

- Familysearch.org (extracted 7 June 2024). Abdul Rahim Munshi

- Unknown (extracted 7 May 20204). Fordsburg and Oriental Plaza – Johannesburg. (https://www.sahistory.org.za)

- Unknown (extracted 7 May 2024). Fordsburg. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki)

- Unknown (extracted 7 May 2024). Indian South Africans. (https://www.krugerpark.co.za).

- Unknown (extracted 7 May 2024). Indian South Africans, (https://www.sahistory.org.za)

- Unknown (extracted 7 May 2024). Munshi (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.