Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 1996, George Zondagh, then Chief Architect at the Department of Public Works, set out a few ideas about the role of the Department in heritage preservation. Although some parts of the article are out of date, many of the key principles are just as relevant today as they were two decades ago. The article first appeared in Restorica, the joural of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (today the Heritage Association of South Africa). Thank you to the University of Pretoria (copyright holders) for giving us permision to publish.

Not only must state buildings be properly maintained and conserved, but they must be promoted as part of the bringing together of this nation, so that a new future can be forged out of yesterday's heritage. Whether it is recognised or not, this is the only heritage we have. We must build on it, refine it and put it to such use that those who will come after us will be grateful for the generation of today.

Although South Africa's history does not date to antiquity, the country has a noble heritage in the buildings built through the years. Time is mentioned to put into perceptive how long the Department of Public Works has been about.

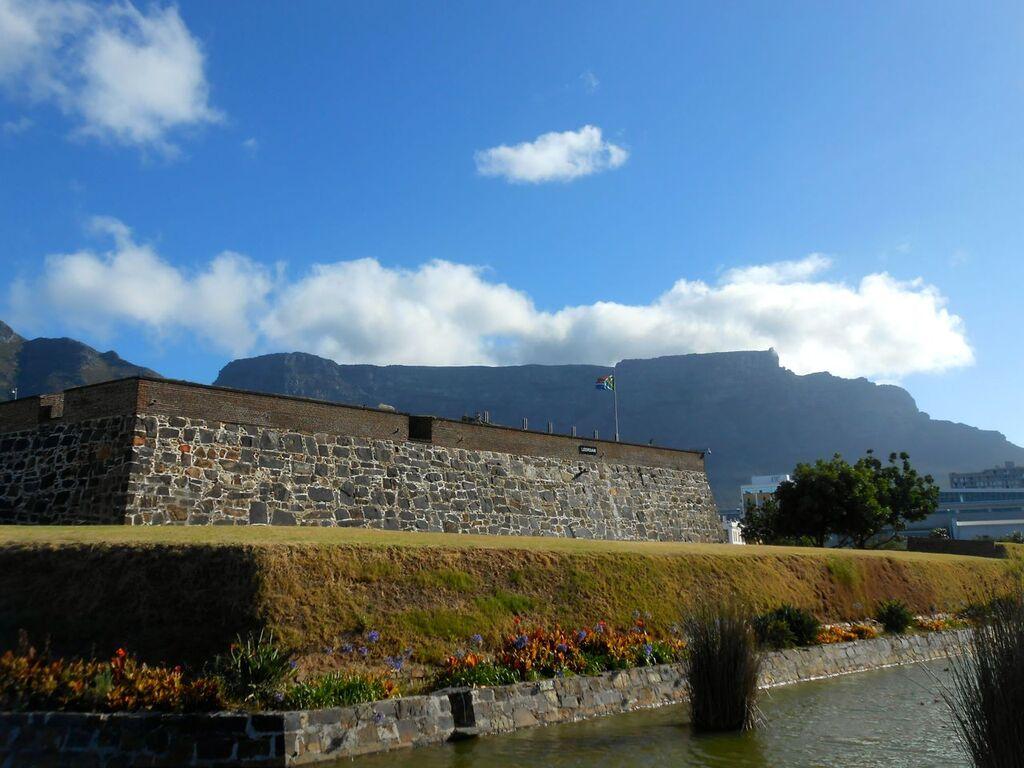

Since the building of the Castle in Cape Town after Jan van Riebeeck had landed there, Public Works, not quite in its current guise, has provided and commissioned public buildings for many clients and users. This does make Public Works the oldest Government Department in South Africa. It is therefore also relevant that the department is charged with the safekeeping of some of the oldest, imposing and culturally rich man-made edifices. These have survived onslaughts from the elements and more dangerously, man.

The Castle (The Heritage Portal)

The variety of buildings collected over the years cover a range of works. The most magnificent of these include the Castle, Groote Schuur, Tuynhuis, Union Buildings, Palace of Justice, Appeal Court and Libertas, to name but a few. These buildings reflect the richness of the past, but also point towards the future as they play an active role in today's society. They serve the government with much needed accommodation and act as drawcard for visitors and tourists.

Palace of Justice (The Heritage Portal)

These structures are but a few examples of buildings that are monuments and well known. The question is, what about the buildings in our countryside, gems in their own right, which do not attract the same amount of attention and money. These buildings usually form the centre of small towns and reflect the use of local construction materials and construction methods. Each of these has its own story to tell and is in its own right worthy of conservation.

Some smaller places like Hanover, Heidelberg, Kroonstad and many others can boast with examples that grace the countryside. Police stations, magistrate's courts and gaols can be found throughout the land. Add to these, schools, houses, post offices, hospitals, military bases, and museums and the full picture become known. Some of the strangest examples are a Jewish Synagogue, a variety of blockhouses, houses in the Knysna woods and even a number of overseas buildings that are monuments abroad.

Heidelberg Town Hall (The Heritage Portal)

The main concern about these buildings is that they have to be adaptable to new and varied uses. This is where a distinction must be made between preservation and conservation, because of the way in which governments need to adapt their buildings.

Preservation is to keep intact without change, whereas conservation is to keep the building in use with the necessary changes designed to ensure its viability - both points of view are valid, but the second appears more applicable to government buildings.

The adoption of the second approach has led to the general belief that the government does not maintain the buildings in its care. This cannot be further from the truth and can be put in perspective by looking at PWD' s total responsibility.

Expensive to run

Public Works has in the region of 69 000 buildings in its care, of which those listed as monuments plus those recognized as worthy of conservation do not number more than a few thousand. These buildings are more expensive to run and maintain, leading to other problems.

Government is not immune to the many problems of the day. It is difficult to compare with countries more advanced in aspects of restoration, but to reach an informed departure point, comparisons have to be made. The Secretary of State in Britain said: "The government is not immune to the problems - financial and other - that face all owners of historic buildings, but should set the best possible example in caring for its historic buildings." This is so much more true in the new South Africa where the government of the day has many other priorities. However, this does not remove its responsibility to preserve the public heritage.

Marshall Street Barracks (The Heritage Portal)

Policy document

Public Works is drawing up a policy document with a view of forming a coherent and well directed approach to the historical buildings in its care. Some factors that have to be considered are:

- There are buildings in government care that may be worthy of listing, but have not been listed. Where such a building is likely to be affected by a development proposal, the government should consult with the NMC and other interest groups. This is a two-way process, where both parties should discuss the problem and search for a suitable and acceptable solution. An example where this process has failed is the Palace of Justice in Pretoria. Built in the period 1896 1902, with a delay during the Second Boer War, the building suffered immense abuse with the addition to the north facade of an additional structure that blocked the original facade and beautiful entrance. The listing of this building was a matter of long debate between the government and the NMC. The outcome of the process was that a compromise could not be reached and in this instance the system for the conservation of such a building failed, luckily not with dire consequences. For the Palace of Justice everything has eventually worked out for the better. The intrusive north wing has been demolished and the full restoration of the rest of the buildings is being finalised. There is therefore a clear path ahead - closer collaboration between the government and national conservation interest groups needs to take place. All parties have a broad base of knowledge and experience that have to be wisely put to use. Our heritage is not that big that it can be squandered, and especially not the buildings in government care.

- A frequent case of bad restoration is the demand that a historical building should be made suitable for purposes for which it was not designed. Government is more often than not guilty of this, mainly at the request of its clients. When the new purpose is not too far removed from the original purpose, all is fine. The adaptation can be made, however, it must be remembered that Public Works is the only legal owner of the buildings. A work of art always has two owners and the other owner is the moral owner, that is, the whole community - born and unborn because all works of art are part of the National Heritage. It is therefore imperative that a transparent, structured approach should be adopted for the conservation of buildings.

- Where these buildings cannot be adopted for alternative uses, they should be offered to other government departments. If this fails, they should be put out to open tender, and sold to the highest bidder. The demolition of historic structures must only be seen as absolutely the last resort and only when it can be proved that all steps have been taken to retain the building and a new use found for it.

- Many old skills are dying out. We need desperately to train our own craftsmen so that these trades do not get lost. For some aspects of restoration, tradesmen have to be imported from overseas at a huge cost. Training is included in the scope of the National Public Works Programme that forms an integral part of the task of Public Works. Therefore certain dying crafts like stonemasonry, carpentry, specialist painting, etc must be promoted and encouraged. Public Works can play a vital role in keeping alive these essential trades needed for the proper conservation of our heritage.

- There is also the question of other state departments playing a more important role in the upkeep of the historical buildings. This would be a question of education and proper communication. They must be kept liable for the damage done and no changes to the buildings should be allowed without Public Works giving the go-ahead.

- A register would have to be set up with supporting documentation about the buildings in state ownership. This list would have to be kept up to date and be freely available to anybody that wishes to look into certain aspects. This could be done in close cooperation with the NMC. Much of the documentation is available, but must be compiled as a cohesive register.

These are but a few broad outlines towards a Public Works conservation policy that still has to be fully developed.

The author, together with Cliff Green and Susan Pyke, forms a small group responsible for the historical buildings in the care of Public Works. They are consulted on the various aspects relating to restoration and conservation.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.