Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

Irving Lissoos earns his living as a highly respected, specialist urologist. He consults and operates from Milpark Hospital. But his life embraces other enthusiasms, among them a love of Johannesburg, partially illustrated by his membership of the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust. Lissoos’s guided tours through Joburg’s old cemeteries in Braamfontein and Brixton are always sell outs. Lissoos lives in Victory Park. He grew up in Berea, attended Yeoville Boys’ and King Edward’s schools. I arrived in his rooms one day armed with a tape recorder and one or two simple questions, asking him to talk about his early life. Nothing had been planned. He quite spontaneously and easily advanced down ‘memory lane.’ He told me with many chuckles and obvious reminiscent enjoyment, about a social existence, the world of his childhood and youth, which no longer exists:

Braamfontein Cemetery (The Heritage Portal)

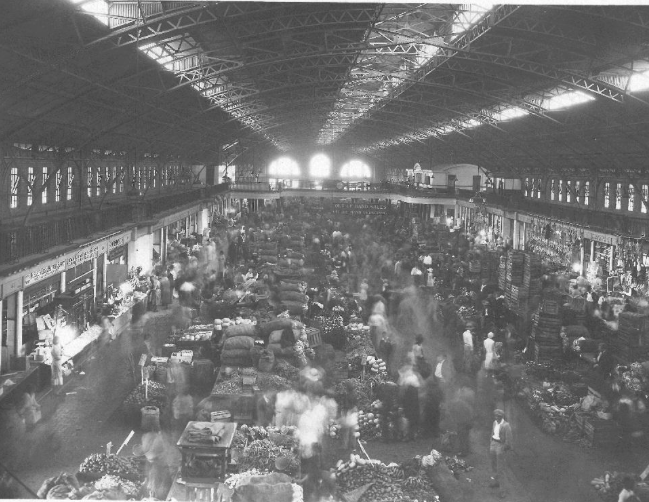

‘My mom was born in London. Her father was a cabinet maker who came to Johannesburg just after the turn of the 20th century. She went to school in London but never got a chance to go to school here because her mom died and she had to look after six brothers. My dad came from Lithuania, like most Jews in South Africa. His father, my grandfather, ran an inn in Lithuania but when he came to South Africa he didn’t do much, he just seemed to sit and study. My father went to school until the age of twelve and then he went to work at the produce market in Newtown, where he worked for the next sixty years.

Inside the Newtown Market (Museum Africa Archives)

‘We lived in Berea in Doris St. Two blocks from where we lived was the Berea Shul. My parents weren’t that religious, but they were traditional. Next door, my friend David was very religious and because of him I became involved with the shul, worshipping on Friday evenings and Saturdays. Then later I went to a thing called Cheder - Hebrew classes, run at the Berea Shul every afternoon except Fridays. They were classes to prepare youngsters to recite in Hebrew at their barmitzvah ceremonies. And you’d go to cheder and you hated it because it interfered with your sporting activities at school, but nevertheless you went. The thing about going to cheder was to make the teachers as miserable as possible. One evening we locked two teachers in the school. We never found out how they got out. They were foreign Jews from Eastern Europe with accents and that, and we went out of our way to make their lives miserable. Most of them had terrible tempers. I suppose we couldn’t blame them because we really pushed them. They’d grab you and hit you, beat you. In retrospect, they were probably quite tolerant because we really drove them to extremes. They taught us Hebrew and their medium was English.

‘All our parents could speak Yiddish but my parents didn’t speak Yiddish to me. My friends knew Yiddish because their parents spoke it to them, so I learnt a certain amount. I can understand Yiddish. I knew that when my Mom and Dad spoke Yiddish about me, I was going to get a hiding. It was a very close knit community, we all lived in the same street, we popped into one another’s houses. We celebrated Friday night meals together, Jewish holidays together. My friend David’s father had a tie factory and I remember every Jewish holiday I used to get two new ties as a present, which I quite looked forward to. I remember two incredible people at the shul. A cantor, a man called Mr Mandel who had the most magnificent voice. To go to services, to listen to this man singing, was a treat. At one stage there was a Rabbi Swift, an understanding man. He used to come to cheder and speak about the Jewish festivals. We were really very fond of him. We always enjoyed his sermons in shul. Next to the shul was a paved area. There, we perpetually played soccer. Waiting to enter cheder you’d play soccer and afterwards you’d play. Sometimes when the Rabbi got up on a Saturday morning to give his sermon the young people would bunk out to play a soccer game. But as we got older and we began to appreciate his sermons we stayed in to listen.

‘Berea shul [today an Ethiopian church], was opposite Barnato Park in Tudhope Avenue. Next to the shul was a little hall and on the Sabbath all the old gentlemen who’d finished praying would sit around a table, discuss what was happening in the world, open a bottle of brandy and pass the brandy around. It was a social thing shul, for these people. It was also a social thing for the young people, the girls and boys. You went to meet your friends and as you got older, you became interested in the girls sitting upstairs. The girls also came to shul to meet boys. It was a social centre and the community revolved around the shul. There was a choir and all the young men who could sing, sang in the choir. I couldn’t sing.

‘The congregation at one stage must have been two hundred families, mainly from Berea. Yeoville and Berea were the main shuls. Later, other shuls developed. The Reform Shul in Paul Nel St was well established but my family and friends didn’t go there because we belonged to an orthodox congregation. They had wonderful Rabbis there. We went if a friend was having a barmitzvah but not otherwise. It was a place you didn’t go to.

‘I went to Yeoville Boys Primary School. I walked to school, across Harrow Rd and through Yeoville. My family never had a motor car so even when it rained or was miserable, I walked to school. School was a great place; there was a great togetherness and we had wonderful teachers. In grades one and two I was taught by Miss Sieve, she must have been at the school for thirty, forty years. She gave you a good foundation to start your career at school. Then you moved up into the standards. The Afrikaans teacher was a man called Geldenhuis, he took us for soccer. Then there was a man called Hurd who later became the Headmaster at Athlone Boys High School. He had quite a temper, I seem to remember that when he got cross he became quite physical and violent. He taught swimming. There was no pool at the school but for our swimming period, we ambled three blocks up the road to the Yeoville Baths. We had a very good soccer team. My good friend Avroy Fanaroff now a famous medical man in the States, was in the team. Ali Bacher played in the team and so did Ronnie Kasrils. The team won the under 11 soccer cup one year.

‘Miss Bouquin taught the standard fours and fives, all the subjects except Afrikaans. She was a very good teacher. She had a cane. She’d say, “Come up to the front of the class. Bend over! Here comes the good old backhand.” She never hit us on the forehand. Mr Green taught the standard fours, a great teacher who later became the Headmaster. In my day the headmaster was a Mr Leach. He’d lost some fingers on one hand, but it didn’t inhibit his caning ability. I remember, one morning our teacher left the class for something and there was a riot; we started throwing things at one another. Leach, whose office was nearby, came to see what was going on. He punished the whole class. He took each one of us into his office and caned us. Standing in the queue outside you could hear the thuds. He caned about thirty of us, quite a physical feat; it took about forty five minutes. But you took this in your stride, getting caned wasn’t a problem. When you were naughty you were sent to the headmaster’s office and he caned you. Depending on the degree of your naughtiness the caning varied from two strokes to five or occasionally, six. Of course you were an inveterate criminal if you got six cuts. It wasn’t a problem, you got caned and that was that. Our parents didn’t complain. In fact they shouted at you for being naughty. It wasn’t an unusual thing to get caned; if you didn’t get caned there was possibly something wrong with you, not a normal little boy. When Green took over he had all five fingers and his canings were much harder. But today, on reflection, I can’t understand how we were caned in cold blood.

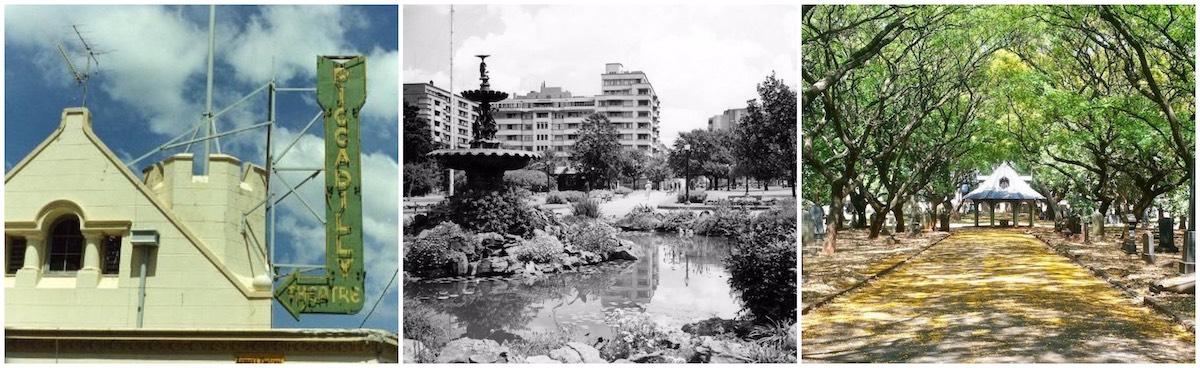

‘In the afternoons we played soccer and cricket at the Yeoville field on Raleigh St, which was a bustling shopping centre. We bought toys and bicycle parts at the Bicycle Shop. I remember a child crying for something he wanted. The owner said,”listen my boy, go and cry at home, then maybe you’ll get what you want.” Hub Stores was a haberdashery shop, the Apollo Milk Bar opposite the swimming baths was quite a social centre. After your swim you’d go across to the Apollo and have a cold drink and a game of pinball. We used a scholar season ticket; you paid a ridiculously low sum and you could use the swimming bath every afternoon, but you had to be out by four-thirty when the local swimming team started training. Later they built the Piccadilly cinema. When it opened they let us scholars see the first performances for free. We saw interesting movies there, the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth and the famous, Hilary conquering Everest, film. The Piccadilly was modern. It had seats that slid back so when someone wanted to walk past, you didn’t have to stand up. This was marvelous, modern technology at its best.

Signage for the Picadilly Theatre

‘Then there was the movie house which we called the Yeoville bughouse. Later it became a branch of OK Bazaars. On Saturday afternoons, that was the place to go. You paid sixpence for seats in the first ten rows. As the lights went off you went and sat in the back. The usherettes who ran the place were perpetually at war, pushing us back. The program always started with a serial, Dick Tracy or that Chinese detective, Charlie Chan and a cartoon. Then there would be interval and after interval there’d be the main movie, usually a western, Gene Autrey or Roy Rogers, Charlie Chaplin perhaps. Before the main feature the manager always came onto the stage to make an announcement or two and he always wore an evening suit, unbelievable. But we always gave him a hard time, shouting and booing, unless he was announcing a new serial, when we cheered.

‘If you wanted to swop comics you went to the Plaza cinema in town on a Saturday morning. At the Plaza you usually got a free ice cream as you went in. There were two other nearby cinemas in Hillbrow, the Curzon and the Clarendon. Those you only went to on a Saturday night, or on a big occasion. If you occasionally went to the Curzon on a Saturday morning, they frisked you for cap guns which the kids used to fire at the villains in the movie.

‘Above the Curzon, was a continental confectionary and tea room called The Florian. You sat upstairs on the balcony with your milkshake and you watched the trams go by. The trams to Yeoville were the B trams. The B-one went to the terminus at the corner of Bedford Rd, and Louis Botha Ave, near KES. At least once a year the tram jumped the rails, ran across Louis Botha and smashed into the wall opposite. It always made headlines in the papers. You could see the permanent wheel marks in the tarmac. You used scholars’ tickets on the trams until four in the afternoon. If you were playing soccer or cricket away, you went to the Headmaster’s office and he would stamp your tickets allowing you to travel after four. At one stage of our careers we got Indian Ink and a stamp pad and we made our own stamps. We never got caught. I think the conductors knew what we were doing but they just let it ride.

Tram moving down Main Street (via Les Pivnic)

‘You went everywhere by tram. I remember when I was very young, before I went to school, we had a maid called Elsie; she was my nanny. She used to take us to the Zoo. We caught the tram to town, changed trams at the City Hall and went all the way down Jan Smuts Ave, to the Zoo. Elsie, being black, was barred from traveling on ‘white trams,’ but she was allowed to sit upstairs if she had white children with her. Likewise at the Zoo, she was allowed in with white children. Sad when you look at it, that the lady who played such an important part in my life, was so degraded.

‘We all had live-in maids. They lived in the back yard in servants rooms. They did the housework, cooked, looked after the kids. If you were black you had to be off the streets at ten in the evening. Beyond that time, there was a pernicious system known as the ‘special.’ An employer had to give black people a note allowing them to be out. This was before the pass or reference book system. My grandparents couldn’t write and when I was ten or eleven I had to write the special for a man who’d served the family for longer than I’d been around. I remember the wording, ‘please pass boy, John, to City and suburbs until, whatever time.’

‘John was expert at Jewish cooking. Whenever there was a family celebration, a barmitzvah or a circumcision ceremony he would phone: ‘John speaking, how much chopped herring do you want for the whatever?’ I had the feeling that John could understand Yiddish, like a cobbler’s black assistant in Harrow Rd, who could speak Yiddish fluently. The cobbler insulted a customer in Yiddish and she sued him for defamation. She won her case when the assistant was called as a witness because he could understand Yiddish.

‘Down Harrow Rd [now Joe Slovo Drive] was Beit St, in Doornfontein, a Jewish area. You could walk or catch a tram, but that meant changing trams in town. There was a kosher confectionary and delicatessen called Crystals where you could buy Jewish delicacies, chopped herring, chicken, polonies, pickles. It was also a meeting place. On a Sunday morning, it wasn’t open on Saturday, you’d go down to Crystals to shop, to drink coffee, to chat. The old people would gather there. On Beit St, was a movie house called the Apollo, which showed a better class of movie there than the Yeoville place. Two blocks from Crystals was the Jewish Aged Home in The Turrets, a house that had originally belonged to Sir George Albu, famous Randlord. The old people used to amble down to Beit St, meet old friends, they’d sit on the benches, watch the trams go by, so they weren’t isolated. Later they moved the aged home to Sandringham. The facilities were better but the oldies were cut off from the wider community.

Apollo Theatre, Doornfontein (sourced by Marc Latilla)

‘I had my Barmitzvah at the Jewish Aged Home. My grandfather was on the committee; he was quite involved in the running of the home and it was a family custom for all the boys, to have their barmitzvahs at the little shul there. Later family generations celebrated theirs’ at Sandringham Gardens.

‘We walked to Ellis Park on Saturday afternoons, to watch rugby. It took about twenty, thirty minutes. We also watched cricket there, when the Wanderers was being moved to Illovo to make way for the new Railway Station. We watched England’s Hutton and Washbrook make that enormous opening score, over three hundred in a test match. My dad loved cricket, surprising for someone who came from Eastern Europe. When there was a test match I didn’t go to school. My mom got upset about it but my dad said, ‘No, he must go and watch cricket, he’ll learn much more than by going to school.’ So my mom gave me a packet of sandwiches; you’d tootle down Harrow Rd, and you’d spend the day at the cricket. It was quite nice. We sat on the popular side, on the grass. If it got boring you could have a kip, or play your own game of cricket with a tennis ball, or soccer. I remember one Saturday afternoon, Athol Rowan, playing for Transvaal, bowled out the Australians. He took ten wickets. And Ellis Park wasn’t expensive, everybody could afford it. It was great!

‘Also on Saturday afternoons we watched soccer at the old Wanderers; Rangers, Marist Brothers, Germiston Callies, they played in the league. You’d catch a tram down Twist St, walk across Joubert Park, and you’d watch soccer on a scholars’ season ticket which cost you two bob. Scholars could sit on the grass behind the goals; no fences, no moats in those days. I remember Lubbe Snoyman was the Rangers goalie. He always stood out in a bright yellow, polo neck jersey. There were a whole wad of Snoymans, ten brothers and a sister, they formed their own soccer team. The sister played in the team. One Snoyman was a wrestler, another, Phil Snoyman, a sports reporter for the Rand Daily Mail. Wanderers was the sports centre of Johannesburg. When they moved to Illovo there was nothing but veld and a bluegum forest next to the club. Eventually town moved out to that area. The old Wanderers was accessible to everybody, it wasn’t easy to get to the new Wanderers; you had to take a bus down Oxford Rd.

Wanderers from above

‘Sometimes we visited Joubert Park, played on the swings, walked around, you could even pop into the Art Gallery to look at the pictures. Often you didn’t know what you were looking at but it was a nice outing. There was a bandstand in Joubert Park; on a Sunday afternoon, you could listen to concerts played by the Salvation Army Band. At a park in Berea, called Mitchell Park which occupied a whole block, we used to run round the grass perimeter training for sports competitions. Another park on the corner of Harrow and Abel was known for its very high slide. Gathering courage to climb the steps and launch forth was a test for youngsters. Sometimes, parties unknown would wax the runnel and you’d shoot off the end.

1950s postcard of Joubert Park

‘From our house, it was a three minute, bicycle ride to King Edward School. From Yeoville, I wasn’t transferred to KES, but to Highlands North High School. KES seldom took boys from Yeoville. My mother said, ’This is total nonsense!’ She went to see the Headmaster who said sorry, he couldn’t take me, so she went to see the Inspector of schools. He told her there was no room at KES and she told him she was going to sit in his office until her son was admitted. An hour or two later I was admitted to KES.

KES (The Heritage Portal)

We did art and manual training as subjects in form one. Most of us in woodwork, made little cricket bats. There was always a game of cricket going on in the manual training centre. Our art master was a Welsh chap named Tammy Mills. He was bald, with a pink, hairless head. Each year the form twos were waiting for the new boys. They told them that Mills had had an accident; he’d fallen on his head and surgeons had inserted a metal plate in his skull but, Mills no longer had any feeling on his pink scalp. Mills would demonstrate art sitting at his table. We’d all crowd around him and one bold gentleman would paint Mills’ head. Of course Mills could feel, and he go berserk. He’d pick up the perpetrator and beat him. He’d scream, ‘Every bloody year some idiot paints my head.’ Of course you couldn’t wait until you got to form two to continue the tradition. It went on for years, every form one class painted Mr. Mills’ head.

‘The standard of education at King Edward’s was very high, with special strengths in the teaching of mathematics and science. This contributed to my first class matric. The next step was Wits Medical School where I qualified as a doctor. I first specialized in general surgery and finally in urology. From primary to high, to medical school and then on to postgraduate training we were fortunate in having great teachers and we lived and learnt in a very privileged society.’

Update via Northcliff and Melville Times: Irving Lissoos– Urologist and Wits benefactor was buried at Westpark Cemetery in 2011. A stalwart of the Jewish community, he was a founding member of the Victory Park Synagogue and served the King David Schools and Jewish Board of Education. Dr Lissoos pioneered kidney transplants in South Africa.

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.