Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Every time South Africa loses a heritage site, a part of our history and our culture is lost, as well as the possibility of understanding something new about our past. South Africa’s top ten most endangered sites speak of the fragility of our shared national heritage. Whether they are precious archaeological sites, living cultural landscapes, early commercial industrial sites, colonial edifices or working class residential areas, the tenuousness of their survival is palpable in the submissions that were evaluated. The Most Endangered Cultural Heritage Sites campaign is an annual initiative of the Heritage Monitoring Project (HMP) and the Heritage Association of South Africa to identify and raise awareness of cultural heritage sites that are at significant risk from natural or manmade forces.

This year was the first time that the HMP issued a call to the public to nominate sites of concern. Between June and August, more than 46 heritage sites across a range of categories were submitted. The longlist of submissions included cultural landscapes, archaeological and palaeontological sites, built heritage, industrial heritage, burial sites, military sites, public open space and even South Africa’s oldest nature reserve (click here to view).

Over the past few weeks an expert panel of judges has been evaluating the submissions against a set of criteria:

- The significance or importance of the site (most importantly, to the local community)

- The urgency and extent of risks or threats faced

- Feasibility of finding a solution or the feasibility of a proposed solution

- Existence of a local organisation that could help save the site with the necessary support

- A clear mechanism through which the general public are able to provide support

According to Jacques Stoltz, founding member of the HMP, “most of the sites are threatened by a combination of poor heritage law enforcement, mining licences being issued in complete disregard of our heritage, urbanisation, under investment, poor state asset management and the seemingly endless delays in resolving land claims and the limbo that many communities still find themselves in in the shadow of apartheid.”

On a more promising note, the list also shows the incredible courage of individuals and local organisations fighting uncaring administrations, developers, powerful international and local mining interests and natural forces. Stoltz notes “While the list should have been more representative of our national and regional diversities and our varied geography and landscapes, we hope that the first campaign has not only highlighted pressing national concerns but also the creative ways in which communities are responding”.

On 21 September the judges decided on the final list of sites (in alphabetic order):

1) amaMpondo Cultural Heritage Landscape, Wild Coast, Eastern Cape

Why this site matters

The amaMpondo landscape, in particular the communities of Sigidi, Mpindweni, Mdatya, Mtolani, Gobodweni, Mtentu (aka Nyavini) and Mabaleni, should be viewed as a living cultural heritage landscape. It is a landscape that is expressive of a traditional agrarian system characterised by vernacular infrastructure and architecture, locally bred agrarian crops and livestock and specific techniques, knowledge and skills related to the cultivation of these crops, and related cultural activities such as rituals, festivals and spiritual beliefs. In the face of the construction of the Wild Coast N2 toll road and proposed mining, the community’s passion for preserving their cultural heritage is remarkable. Yet, to date, the landscape qualities and values, as well as the intangible elements associated with the landscape and agrarian ways of living, have gone mostly unrecognised by authorities, despite the area drawing local and international tourists. In the judge’s view, given the dichotomy between heritage and development, a determination should urgently be made on whether the entire amaMpondo cultural landscape should be preserved or parts thereof that reflects or offers an authentic heritage experience.

Why this site is endangered

These Pondoland villages are surviving vestiges of a traditional, agrarian way of amaMpondo life that was largely destroyed by the ‘Betterment’ schemes of the late 1950s and which culminated in the rural insurrection known as iKongo, or the Pondoland Revolt of 1960.

Today, there is a strong push from government to develop the Wild Coast N2 toll road. In addition, the area has been earmarked for open cast mining. Development poses a serious risk to a traditional way of living and if a balance is not struck between heritage and development, the former will be a loser as it is a non-renewable resource.

Local champion

Sustaining the Wild Coast

Traditional umzi and fields near Mtentu (Sustaining the Wild Coast)

2) Buffelsjachtsrivier Bridge, Overberg, Western Cape

Why this site matters

This 9-span bridge was constructed by the Higgo Brothers to the design of Charles Michell completed during his tenure as Surveyor-General and Engineer of the Cape Colony in 1852. The Bridge comprises stone-clad piers, timber joists (with timber knee braces) and timber decking salvaged from a wreck in Gordon’s Bay and transported overland to Swellendam for construction of the bridge. It is said that molasses (grown in plantations between Swellendam and Malgas) was used as binding agent for the Gypsum Bedding and Grouting of the Stonework Cladding (hence the nickname of “Sugar Bridge”).

The bridge is believed to be the third oldest bridge of historic significance in South Africa and the site is a graded provincial heritage site. An innovative local initiative seeks to rehabilitate the bridge, as a fully functional bridge for the local community, however a lack of sufficient funds constrains implementation of the redevelopment scheme. In the view of the judges, the redevelopment proposal demonstrates how heritage structures can be repurposed to address the needs of the present, connect spatially fragmented communities, stimulate job creation, boost tourism and conserve an important piece of civil engineering history.

Why this site is endangered

The bridge has been severely neglected and its deterioration poses a considerable environmental risk. It is also at risk from further flood damage.

Local champion

Swellendam Heritage Association

Sugar Bridge (via Marcus Holmes)

A wider view of the Sugar Bridge (via Marcus Holmes)

3) Canteen Kopje, Barkly West, Northern Cape

Why this site matters

Canteen Kopje was declared and gazetted as a protected National Monument in 1948. The archaeological site covers a long sequence from the Earlier Stone Age to Later Stone Age, the Iron Age and colonial contact period. The site has a provisional basal date of 2.3 million years and is one of the most important Early Stone Age sites in South Africa. Its preservation is considered of critical importance to the scientific community and it is an invaluable cultural resource.

Why this site is endangered

So many sites associated with the pre-colonial history of the country are under threat and their loss is inconceivable. They form a vital component in the understanding of the development of the country. If this site is lost we will lose the record of life spanning many thousands of years and with it, the possibility of understanding something new about the deep past.

Mining in a declared heritage site sets a precedent that imperils all South African archaeological sites. The danger is real and present. Without the actions of the heritage community, including the McGregor Museum, this site would already have been lost to the present and the future. While a High Court ruling has prohibited further mining, the decision by the Department of Mineral Resources to grant a mining permit over a heritage site holds serious implications for Canteen Kopje and other similar sites across the country.

Local champions

McGregor Museum, Sol Plaatje University, Historical Society of Kimberley and the Northern Cape Provincial Government

Illegal Mining at Canteen Kopje (David Morris)

Archaeological Research at Canteen Kopje (David Morris)

4) Central Mill Rimers Creek, Barberton, Mpumalanga

Why this site matters

Rimer’s Creek (originally known as Umvoti Creek) is an area of public open space situated in the historical heart of Barberton. It is on the threshold of the site of the Barbers family’s gold discovery in 1884 that led to a gold rush and where the Rimer Brothers (James Cook and Richard Guy) made a further discovery shortly thereafter. It is the site of the historic Central Mill where the ore from their early workings was crushed and where the first ore from the historic Sheba Gold Mine was sent by Edwin Bray in 1885.

The mill was owned by a syndicate to which the Rimers and Barbers belonged and was the nucleus around which Barberton developed. Rimer’s Creek is where Barberton was born in 1884 when David Wilson, the Mining Commissioner, broke a bottle of gin on a rock and christened the town Barberton after the Barbers. It is situated in what will eventually constitute the gateway to the Barberton-Makhonjwa Mountainlands area – a site on Unesco’s World Heritage Tentative List.

Why this site is endangered

A heavy truck parking lot and pipe storage yard have been approved for the historical site of the Central Mill in Rimer’s Creek in the midst of heritage homes, declared provincial heritage sites and residential properties despite vociferous objections from the local community. The site is threatened by the development and undermines the precepts of the law. The case highlights the disastrous effects of a lack of planning alignment between the local municipality and national and provincial heritage requirements and law enforcement.

Local champions

The Umjindi Environmental Committee, the Umjindi Barberton Ratepayers Association & other Interested and Affected Parties

An historic photograph of Rimer's Creek

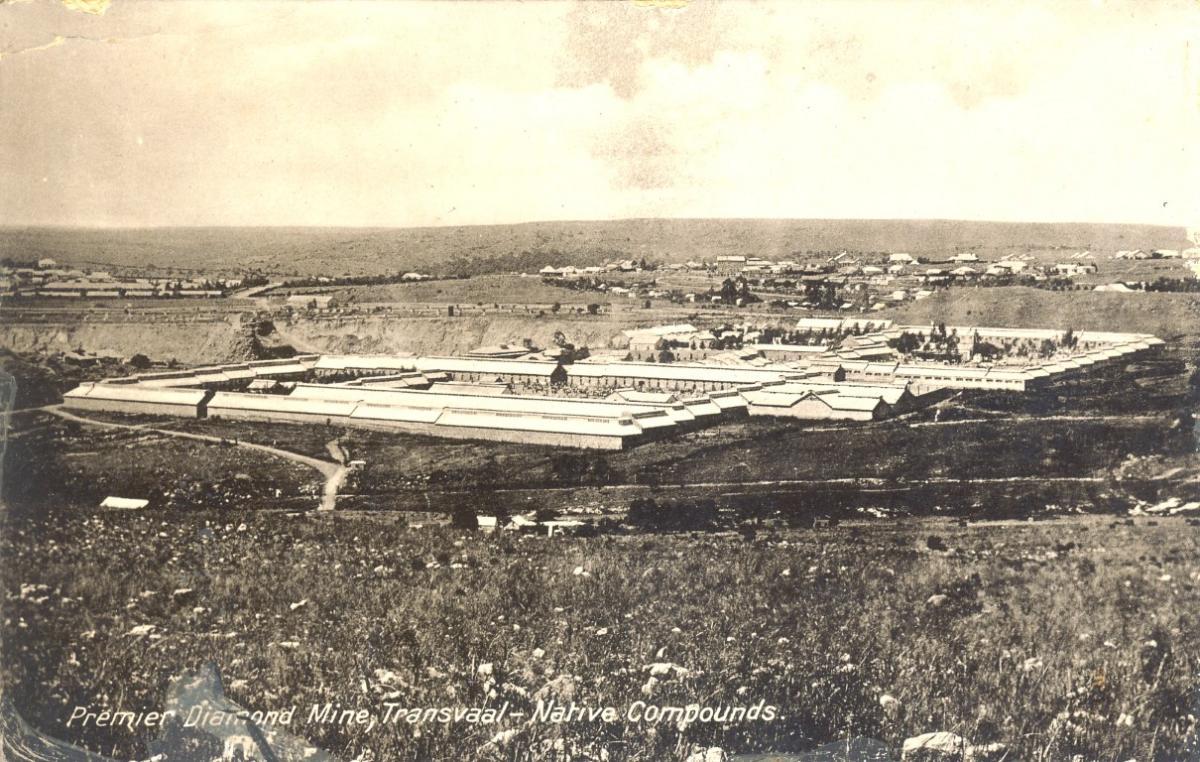

5) Cullinan Mine Workers Compound, Cullinan, Gauteng

Why this site matters

The Cullinan compounds were built in 1908 to house migrant workers employed by the Premier Transvaal Diamond Mining Company. It used to house up to 15,000 Black mine workers who came from all over Southern Africa and were segregated along strict colonial - and apartheid era ethnic lines (surviving death registers that were salvaged by heritage activists attest to the sub-continental reach of Cullinan’s labour pool). During the Second World War the compounds, as with the rest of Cullinan village, were taken over by the army. Italian Prisoners of War (POWs) housed at the nearby Zonderwater constructed a fountain at the site. In 1945 the mine resumed operations. Like many other Black mine worker compounds across the interior of South Africa, the history of the site has largely been forgotten and is invisible to the many tourists who visit Cullinan today.

Why this site is endangered

The compound was abandoned in 1971 and is in a bad state of repair. The associated graves are also in an appalling condition, while the fountain is at risk of being completely overgrown. As the site falls within a mining area, access is restricted and the buildings are neglected, overgrown and at risk of deterioration and eventual collapse. While the current owners of the mine argue that the site is hazardous, there is a local heritage community in place that is committed to researching, documenting, promoting and exposing the site to locals and visitors as an integral part of Cullinan’s mining heritage. However, to date access remains restricted and efforts to have Cullinan declared as a heritage conservation area has met with little success.

Local champion: The Cullinan Heritage Society

An old postcard showing the compounds

6) East Fort, Hout Bay, Western Cape

Why this site matters

East Fort Battery c.1782 is one of four coastal fortifications built and developed in Hout Bay during the period 1781 – 1806. Hout Bay was seen by the government of the day as the soft-underbelly of Cape Town, exposing it to a possible marine invasion from the South. East Fort was established in 1782 and consists of a 6.4-hectare site which is today bisected by Chapmans Peak Drive, part of our country’s No 1 scenic route. However, little information regarding East Fort’s important role in our country’s history is provided near to or at the site and it remains an enigma to the many passing tourists. The site includes four ruined buildings (most of which could be restored) and a battery of 8 x 18 pdr guns which have been restored, proofed and licensed by the Hout Bay & Llandudno Heritage Association and have been ceremonially fired on many special occasions by the Association’s “Gunners”. Given its location the site has significant redevelopment potential as a heritage tourism destination.

Why this site is endangered

Little or no maintenance is currently done or protection given to the fabric of the site by the responsible authorities, walls are collapsing, it is subject to vandalism and exposed to fire damage, two major ones having occurred since SANParks took over the site.

Local champion

Hout Bay & Llandudno Heritage Association

East Fort (Dave Cowley)

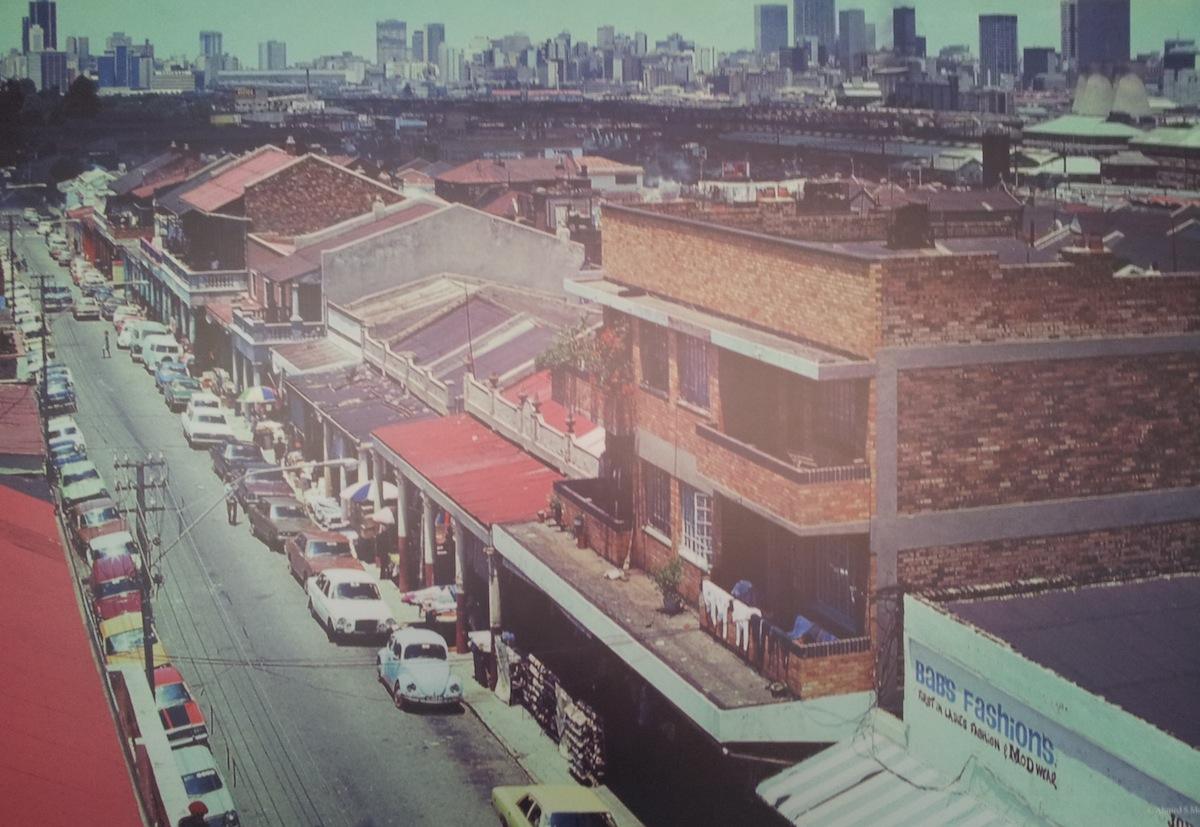

7) Pageview, Johannesburg, Gauteng

Why this site matters

The “old Malay camp” dates back to the South African Republican period when the Kruger government established the area in 1893/4 for a predominantly Coloured and Malay community. When the neighbouring ‘Coolie Location’ was evacuated and subsequently burnt to the ground in 1904 (ostensibly in response to the outbreak of bubonic plague) many displaced Indian families resettled in the Malay location.

Over time the Malay location would become a predominantly Indian area. With its neighbouring suburb Vrededorp – a freehold area established for poor Afrikaners – the area became a lively multi-cultural community accommodating people from all sections of the population including Indians, Whites, Coloureds, Africans, Malay families and also a Chinese community. Although officially renamed Pageview, for most South Africans the area was simply ‘Fietas’. Following the Group Areas act of 1950, the suburb was proclaimed a White area and in the face of heavy opposition the first eviction notices were served in 1967. In 1975 many residents and businesses were bulldozed with traders relocated to the newly constructed Oriental Plaza in Fordsburg and residents relocated to Lenasia. As with District Six and Sophiatown, this site is related to a very significant part of South Africa’s past – that of forced removals. Despite the demolitions, some significant buildings remain, including the Fietas Museum which singularly keeps the Fietas memory alive.

Why this site is endangered

The threats to Pageview resonate with those faced by similar areas across the country: the loss of historical memory of a particular time in South African history, the seeming never-ending delays in resolving land claims and the manner in which this is reflected in the built environment and in spatial planning. The site also speaks to the attempts made by members of the local community to ensure that their history to keep the memory of the area alive – while the historical fabric deteriorates or is destroyed. This should serve as a source of inspiration to other communities. At the same time, years of waiting for land claims to be resolved means that there has been no investment or redevelopment and surviving buildings are abandoned and at risk of illegal occupation. Insanitary conditions are rife. Empty land parcels dot the landscape. Although a development vision was adopted a decade ago, little tangible benefits have resulted. Efforts by the Fietas Museum to attract visitors and interest in Pageview are undermined by these existing conditions.

Local champion

The Fietas Memory in Action Museum

An old photo of Fietas (Fietas Museum)

Fietas Commemorative Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

8) Pilgrims Rest town, Pilgrims Rest, Mpumalanga

Why this site matters

Pilgrims Rest was established in 1872 and was once a thriving tourist attraction. The Pilgrim’s Rest Reduction Works considered by some to be the first gold-related industrial plant in Africa formed the basis of a Unesco world heritage site tentative submission. However, years of neglect, poor management, theft and illegal mining have caused the town and associated industrial sites to deteriorate. This has threatened the livelihood of entrepreneurs and others who benefit, or may benefit, economically from its presence. It is an example of how heritage can be used to sustain a local economy – but only if the ongoing maintenance and integrity of the site can be secured through responsible government custodianship and proper site management.

Why this site is endangered

If there is no intervention, further degradation of the site will erode the remaining tourism and other local economic benefits the site holds for the area. This will also threaten its existing Provincial Heritage Site Status and any future efforts to reconsider the site as a potential Unesco world heritage site (South Africa removed the site from its tentative list in 2015). The town is neglected and is not being maintained by the Mpumalanga Provincial Government.

Local champions

Mpumalanga Historical Interest Group & local businesses

The landmark Royal Hotel in Pilgrims Rest (Sheila Ball)

9) Timbershed, Plettenberg Bay, Eastern Cape

Why this site matters

In August 1786 the Dutch East India Company decreed the erection of the Timber Shed for storage of timber prior to shipment by sea. Due to its age, this site has great historic significance. The site was declared a national monument in 1961 (Provincial Heritage Site today).

Why this site is endangered

The site is currently for all intents and purposes, a ruin and if not maintained will eventually disappear. The original yellowwood lintels in the windows are buckling and in danger of collapsing. Four beams have already collapsed resulting in the fall of a considerable amount of stonework. The stonework, lintels and walling can be stabilised with the necessary engineering skills and funding.

Local champion

Van Plettenberg Historical Society

Timbershed (David Rowe)

10) Westfort Village, City of Tshwane, Gauteng

Why this site matters

Westfort Village is the residue of the Westfort Leprosy hospital, established in 1897. Its first phases were executed to the design of the ZAR Department of Public Works under Sytze Wierda and Klaas van Rijsse. Its development continued until 1947 when the last construction phase was effected. In the meantime it had grown exponentially when, with the closure of the leprosy asylum Robben Island, Westfort became the only leprosy institution in South Africa, serving a mixed race community of patients. The site lost its medical use in 1997, was mothballed and abandoned, after which it was appropriated. It is now home to a vibrant multi-racial community. The originally isolated sites are being engulfed by fast-encroaching suburbia.

The site represents the evolution of both urban planning in South Africa, as well as the development of medical care from home-based care to large-scale scientific institutions. Apart from these associations it has high aesthetic value, set picturesquely against the southern slope of the Bronberg Mountains and it is a site of national importance in the medical history of South Africa. It is the last remaining example of a near extinct institutional typology.

The new community that has made this site its home can become the new custodians of the site, if granted title and given the proper guidance. This community, if supported, could be enough of a public to guarantee the survival of the site.

Why this site is endangered

Disastrous development plans are already, in part, being implemented. At the same time the inhabitants are scheduled to be relocated. The fact that the site is inhabited and inhabitable is the reason the site still exists. Should the existing community be relocated the site will be stripped of all useful building material and cease to exist. It is clear that the City of Tshwane has not developed a vision for the site, and the 2015 infrastructural developments carried out without heritage values being considered or statutory approvals sought. At the same time the high levels of poverty and lack of infrastructure (electricity) have wrought havoc. Two recent fires have destroyed important structures. Recent service delivery protests have cost two more. If no action is taken Westfort Village: one of the more important heritage assets of Tshwane and Gauteng will be lost in less than a decade.

Local champions

Westfort Heritage Foundation & Tshwane Building Heritage Association

Westfort Leprosy Hospital Building (Nicholas Clarke)

While there will be an annual call for submissions, members of the public can continue to submit sites on The Heritage Portal as part of the ongoing identification and monitoring of at risk cultural heritage resources (email jamesball01@gmail.com for details).

About the Expert Panel

Janette Deacon has a PhD in Archaeology from UCT and in 2016, was awarded an honorary DLitt for her contribution to knowledge of the long history of the indigenous San hunter-gatherers in South Africa. She lectured in Archaeology at UCT for short periods in the 1960s and 1970s and was a Senior Research Assistant in Archaeology at the University of Stellenbosch in the 1980s. In 1989, she was appointed as Archaeologist at the former National Monuments Council and remained in that post until her retirement at the end of 1999. Since then she has served on the councils of SAHRA and Heritage Western Cape, and has been involved in a variety of research and training projects, mainly connected with conservation and management of rock art at world heritage sites in southern Africa. Several projects were undertaken in collaboration with the Getty Conservation Institute. She has published 8 books and more than 170 peer-reviewed papers and popular articles.

Nicholas Clarke has an MPhil from Cambridge University and is a practicing architect, specializing in heritage. He is currently part time lecturer at Delft University of Technology Dept. of Architecture, University of Pretoria Part and Associate in Heritage and Architecture Heritage Studies. Associate He also runs his own company, Archifacts Architects and Heritage Consultants. Clarke is widely published.

Jo-Anne Duggan is the director of the Archival Platform an archival research, advocacy networking initiative based at the University of Cape Town. Before taking up this position she worked extensively in the heritage sector: in national institutions and with civil society initiatives and across a number of fields including policy formulation, institutional planning, research, curation and exhibition development.

Jacques Stoltz is an MPhil graduate (Urban Infrastructure Design & Management; UCT) and works as an independent development consultant at Place Matters specialising in urban research and development with a particular emphasis on the interfaces between infrastructure, tourism and heritage. He has conducted various studies including a Tourism Transport Plan for Gauteng and is currently part of a team surveying heritage resources along the Corridors of Freedom for the City of Johannesburg. He is a founding partner of The Heritage Monitoring Project and serves on the councils of Better Tourism Africa, the Heritage Association of South Africa and the Egoli Heritage Foundation. He lives in Johannesburg.

Herbert Prins qualified as an architect at Wits University in 1952, received a Diploma in Town Planning in 1973 and a Masters Degree in Conservation in 1990. He was a senior lecturer at Wits University Department of Architecture from 1970 to 1990; Head of Department from 1976 to 1978, being a Member of the Senate in 1981 and 2000, and a member of the Board of the Faculty of Architecture from 1980 to 2000. He was President of the Transvaal Institute of Architects in 1978 and 1979, President in Chief of the Institute of South African Architects in 1982 and 1983 and is presently Chairman of the Rosebank Action Group and a founding member of the Egoli Heritage Foundation. He opened the practice of H M J Prins Architect specialising in heritage consulting in 1995. He was awarded the Gold Medal of Distinction of the South African Institute of Architects, the Gold Medal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (now the Heritage Association of South Africa) and an Honorary Life membership award from GIFA.

Khensani Maluleke currently lectures heritage management at the University of Pretoria. He has a BAED (History) Degree from the University of the North, a Postgraduate Diploma in Heritage and Museum Studies from the University of Pretoria and Postgraduate Diploma in Strategic Marketing, University of Hull. Khensani has travelled extensively visiting heritage sites and doing work in the USA, UK, France, Senegal, Kenya, Mauritius, Tanzania, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, Ghana, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Khensani was a Managing Partner at Matimu Heritage Solutions from (2003-2007) before establishing Khensani Heritage Consulting cc (Converted to PTY LTD in 2014) (a heritage management consulting firm in South Africa with an international footprint) and Sector Based Development Consulting cc respectively in 2009 (Converted to PTY LTD in 2014). He possesses over twenty years (20) of experience in business management and development having been employed by the Transnet Heritage Foundation (Curator Exhibitions) and Freedom Park Trust (Heritage Manager) prior to that. Currently Khensani is a Chairperson of the Gauteng Geographical Names Change Committee. Khensani also serves as a Panel Member for the Mzansi Golden Economy.

André Johan Durand van Graan is Adjunct Professor at CPUT. He has an MPhil Architecture from the University of Cape Town and a PhD also from the University of Cape Town (PhD title: Negotiating Modernism in Cape Town: 1918-1948. An investigation into the introduction, contestation, negotiation and adaptation of modernism in the architecture of Cape Town). He is widely published.

Sadia Nanabhay (Postgraduate Diploma in Tourism Management) has a background in hospitality, tourism marketing and academia concentrating on tourism management and marketing. She has lectured tourism management and marketing at the University of Cape Town, and in 2015 acted as the university’s course convenor for the Postgraduate Diploma in Tourism Management. She works as a researcher specialising in tourism sector research, tourism strategy development, tourism marketing strategy development and responsible tourism. She has worked on projects in Gauteng, the Western Cape and Nelson Mandela Bay. Outside of South Africa, her project experience extends to Namibia and Oman. These projects were undertaken for local, provincial and national government as well as non-governmental organisations.

Tshimangadzo Nemaheni has a Masters in Museum and Heritage Studies from the University of Pretoria. He is currently the director and owner of a recently established heritage consulting company, Sub-Sahara Africa Heritage Solutions. The main areas of focus for this company include Archaeological/Heritage Impact Assessments, Social Facilitation, Strategic Plans and state of conservation of sites. Previous to this, Nemaheni was Head of Department Park Operation for Freedom Park. He practiced Heritage Management at a provincial government level and was appointed Director for Museum and Heritage Services responsible for museums and heritage services in the province. In Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage site he worked as an overall Park Manager responsible for the management of the archaeological heritage and natural environment of the Park. When appointed Senior Manager of the Heritage Department for Robben Island Museum and World Heritage Site, he had to lead the strategic direction of that Department. Nemaheni was in the first team that conceptualised the development at the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site where he was first appointed as Deputy Director for Public Participation between 2000-2003.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.