Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

“At a time when the government took no interest whatsoever in our education, it was the church-founded schools who educated us, and conscientised us to the unjust realities of South African society” – Nelson Mandela

When a young Thembu royal first attended school at the ripe age of 15, little did anyone know that he would go on to change his country and the world. Upon the realization that his days were numbered, Chief Mphakanyiswa Gadla solicited his cousin Chief Jongintaba Dalinyebo to look after his only son. Since both chiefs of the Thembu Royal House were committed Methodists, it was inevitable that the boy would be sent to Chief Dalinyebo's alma mater.

The Mandela Statue at the Union Buildings (The Heritage Portal)

Clarkebury Mission School

Clarkebury had been founded by Methodist missionaries, along with the invading British settlers, during the Frontier wars of the early 1800s. In its heyday it was the leading educational institute in the whole of Tembuland. Like most missionary schools, Clarkebury went into a terminal decline when the National Party introduced its Bantu education policy and withdrew funding for church schools in 1950. When Nelson Mandela first arrived at Clarkebury in 1934 his self-confidence took a beating. This was because he found it uneasy to walk in the first pair of shoes he'd ever owned. The second reason for his uneasy beginnings was because, for the first time after the royal treatment home he'd become accustomed to at his uncle Chief Dalinyebo's great place, at Clarkebury he was treated like any other student. There were other boys with greater royal lineages. Mandela arrived at Clarkebury alongside Chief Dalinyebo's son, Justice. Both boys stayed in the double-story boys hostel, a large building which dominated the entire the school campus.

By his own admission he had a lot of catching up to do. Most of his classmates could outrun him on the sports field and could outdo him in class. The Reverend Cecil C Harris, was a tough disciplinarian who ran Clarkebury like a military instituition. Mandela got to know him and his family intimately. As the first white family that Mandela was becoming familiar with, he spent hours tending to Rev Harris' garden. He also revelled under the fact that Chief Dalinyebo had made a special request to Rev Harris to take his young nephew under his wing. Mandela would later state that he had admired the Rev Harris and the manner in which he administered Clarkebury “with an iron hand and an abiding sense of fairness”.

Healdtown Mission Institute

Mandela spent two years as a student at Healdtown. This elite Methodist institute epitomized an exclusive black academic instituition. He describes it so in his memoir Long Walk to Freedom, “Located at the end of a winding road overlooking a verdant valley, Healdtown was far more beautiful and impressive than Clarkebury. It was, at the time, the largest African school south of the equator, with more than a thousand learners, both male and female. Its gracefully ivory colonial buildings and tree-shaded courtyards gave it a feeling of a privileged academic oasis, which is exactly what it was.”

Book Cover

Even if some students did not excel, Healdtown's founding fathers seemed intent on ensuring that all who studied there should hold their sights high. The school motto ”Alis velut aquilarum” (Latin for “They’ll soar as if with the wings of eagles”) was represented on the school emblem by an airborne eagle.

Intending to further his education and gain skills needed to become a privy councillor for the Thembu royal house, Mandela began his secondary education at Healdtown in 1936. Healdtown's headmaster during Mandela's time was the Rev Dr Arthur Wellington. The Rev Wellington was a staunch English patriot who liked to boast about his links to the Duke of Wellington, the British Army general who had defeated Napoleon at Waterloo.

The British world view permeated Healdtown and an English education model provided the basis for all teaching. ”Lapsing into one's home language was a punishable offence. Walking in the grounds at Healdtown one had to communicate in English only.” recalls anti-apartheid stalwart and Rivonia Treason trialist Raymond Mhlaba.

Sundays at Healdtown provided a vivid display of how comfortably the imperialist and missionary traditions co-existed. On the way to Sunday service, the boys and girls assembled under a Union Jack in the school yard, and accompanied by a brass band, sang the British national anthem "God Save The King".

Thereafter they would sing the hymn “Nkosi Sikeleli Africa”. It was during these weekly parades that the soon to be an anthem was first sung. The song was composed in 1897 by Enoch Sontonga, an Eastern Cape-born clergyman and teacher who was educated at the nearby Lovedale Institute. It was sung in 1912 at the first meeting of the South African Native National Congress, the forerunner of the African National Congress(ANC). The song became a pan-African liberation anthem and was later adopted as the national anthem of five Southern African countries, including Zambia, Tanzania, Namibia and Zimbabwe at independence. Zimbabwe and Namibia have since adopted new national anthems. The song is currently the national anthem of Tanzania, and, since 1994, a portion of the national anthem of South Africa.

In his second year at Healdtown Mandela took an interest in the two sports that he would hold dear to him for all his life, boxing and running. He also became a prefect. Night duty involved patrolling the front of his hostel to apprehend fellow boy pupils who, in typical school lads fashion, insisted on relieving themselves from the verandah, instead of visiting the outdoor toilet.

The housemaster in his hostel was the Reverend Seth Mokitimi. He impressed Mandela by standing up to Dr Wellington. This made the impression on Mandela that a black man did not have to defer automatically to a white man, however senior he was.

According to his own records, Mandela's most memorable experience at Healdtown was during one morning assembly in the dining hall. At each morning assembly, Dr Wellington made a grand entrance through Wellington's door, so-known because no one ever walked through that door except for Dr Wellington.

One morning, however, a black man draped in leopard skin and clutching two spears led the way forward with Dr Wellington following. He was the famous Xhosa poet S.E.K Mqhayi, whose writing was a major source of inspiration for early African nationalists.

Mandela said that when Mqhayi stood up to speak he was not particularly impressed. He said that apart from his traditional garb he was very much ordinary-looking. However, he said that he could hardly believe his ears when, in the presence of Dr Wellington and other white staff members, Mqhayi spoke of blacks having succumbed to the false gods of the white man for too long.

Mqhayi was also renowned for his praise-singing prowess. During this particular performance he raged against foreign cultural influence, vowing that the forces of African culture would eventually overcome it. This got the audience on their feet, cheering and clapping.

Speaking in Xhosa, he took to the stage and exclaimed, ”The assegai stands for what is glorious and true in African history, it is a symbol of the African warrior and artist. The metal wire is an example of Western manufacturing, which is skilful but cold, clever but soulless. What I am talking about is not a piece of bone touching a piece of metal, or even the overlapping of one culture over another. What I am talking about is the clash between what is indigenous and good, and that which is foreign and bad. We cannot allow the foreigners, who do not care about our culture, to rule over us.”

Mandela said that Mqhayi's performance was like a comet streaking across a night sky, and it made him begin to think about his views on colonial rule.

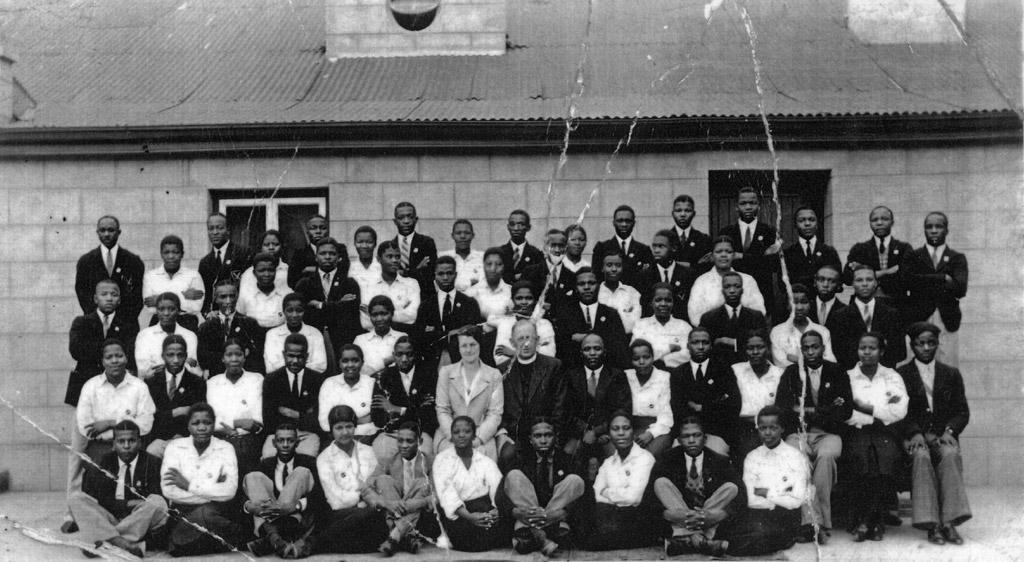

Mandela at Healdtown via Daluxolo Moloantoa

Fort Hare University College

Originally a British fort in the wars between British settlers and the Xhosas in the 19th century, Fort Hare University College, as the current University of Fort Hare was known then, was founded by Methodist missionaries under the stewardship of Reverend James Stewart. It was begun as a school for missionaries from which at the beginning of the 20th century the university resulted. In accord with its Christian principles, fees were low and heavily subsidized. Several scholarships were also available for indigent students.

With Jongintaba’s backing, Mandela began work on a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree at Fort Hare University College in 1940. Fort Hare was an exclusive black institution situated picturesquely on the banks of the Tyume River in the small town of Alice in the Eastern Cape. There he studied English, anthropology, politics, native administration and Roman Dutch law in his first year, desiring to become an interpreter or clerk in the government's Native Affairs Department. Mandela stayed in the Wesley House dormitory befriending Oliver Tambo and his own kinsman, K.D. Matanzima.

Continuing his interest in sport, Mandela took up ballroom dancing, and performed in a drama society play about Abraham Lincoln. As a member of the Students Christian Association, he gave Bible classes in the local community, and became a vocal supporter of the British war effort when the Second World War broke out. Although having friends connected to the African National Congress (ANC) and the anti-imperialist movement, Mandela avoided any involvement. He helped found a first-year students’ House Committee which challenged the dominance of the second-years.

At the end of his first year he became involved in a Students’ Representative Council (SRC) boycott against the quality of food, for which he was temporarily suspended from the university. He left in 1940 without taking a degree. It would take over a half-century to correct the transgression. In 1992, fifty-two years after his unceremonious departure, the University of Fort Hare bestowed an honorary LLD (Law) Degree on its most famous student renegade.

Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg. After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue. On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa. Click here to see more of his work.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.