Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

My maternal grandmother, Antonetta Elizabeth Cosslett, would have turned 100 on the 13th of December 2017. And it is this hypothetical centenary that has motivated me to record what I know about her. I am the third youngest of a very large brood of cousins on my mother’s side of the family, and only really came to know her in her last decade or two, so perhaps there is a sense of disconnection with history that I am trying to mend too. And then, despite the fact that I spent most Christmas and Easter lunches in her company, she was the least coherent and articulate family elder, particularly when it came to her past. Her spoonerisms – “miracle aid” instead of medical aid – were the subject of family jokes, and her descriptions of where she had grown up left me with more questions than answers.

So let me start with what I knew before I started digging:

- She was born on the 13th of December 1917.

- She had married my grandfather, who came from the Cape, in the 1930s.

- They had lived in working class neighbourhoods – first at Wilhelmina Street, Troyeville, then at Highgate Street in Jeppestown, before moving to the slighter better Park Street, in Belgravia.

- They had 10 children, one of whom did not make it to term, and another, Patricia, who died as an infant.

- They were desperately poor, and despite having to fit 10 people into a three-bedroom semi-detached house in Jeppestown, took in a boarder (Mr Gutmann) to supplement their income.

- Their Jeppestown abode had a corrugated-iron outhouse, and the Cosslett children were restricted to a bath a week.

- Granny Cosslett, as she was known to me, spoke vividly of the terror of the 1922 Strike (she was 5 years old when this occurred!).

- She was the source of a rich food tradition: pickled fish, fish cakes and fried fish at Easter; beetroot, potato and bean salads at every meal; coriander was called “dhanya”.

- There was occasional mention of a De Villiers in the family tree, possibly a maternal grandfather. He may have been a magistrate, or perhaps lived near a magistrate court – the facts were never clear.

And then there was the allusion, sometimes whispered or couched in a joke, sometimes thrown out as a hurtful slur in the 21 years of my parent’s deeply dysfunctional marriage, that she wasn’t quite White. That her skin tone was suspiciously olive, her accent questionable, and the food she cooked perhaps a little too exotic to be respectably English or even Afrikaans.

Finding out more was difficult. She didn’t have a birth certificate, and though my mother spoke of family photos, including a possible photo of Granny Cosslett’s mother, they have not been found.

And then, quite by accident, I found a record of her baptism while trawling the digitised archives of the Church of Latter Day Saints. It contains the following information:

- Her baptism was solemnised in St. Alban’s, in the Parish of Johannesburg, in the Diocese of Pretoria on 31 March 1918.

- Her name and declared date of birth are confirmed.

- Her parents are recorded as William George and Kate Kathleen Henry.

- Their address is Saunders Terrace, Marshall Street.

- Her father’s profession is recorded as Trimmer.

- G.H. Ridout was the priest who performed the baptism, and it was witnessed by Sydney James Henry, Francina Antonetta Henry and Jameli Dede.

- There is a note on the page that no doubt refers to the exotically named Jameli Dede at her baptism: “Godmother is an Assyrian Christian”.

A wealth of information! Let me tackle it fact by fact…

St. Alban’s Church

This is today located on the corner of Anderson and Ridout Streets in Ferreirastown. The Johannesburg Heritage Foundation plaque at the church reads:

Founded in 1898 to serve the local Coloured Anglican community, a magnificent church designed by F.L.H. Fleming replaced the old wood and iron building in 1928. The forced removal of the congregation in the 1960s threatened the survival of the church. But in 1960 the offices of the diocese were located here under Bishop Leslie Stradling, who was then followed by Bishops Timothy Bavin, Desmond Tutu and Duncan Buchanan. St Alban's served as the Diocesan offices until 1987. It remains a potent reminder of the forced removal of the Coloured people from Ferreirasdorp and Marshalltown. (Ball, 2017)

The S. Mary’s Parishioner of July 1913 adds more colour:

“…at the end of 1897, a lease was granted by the Ferreira Gold Mining Company, Ltd, of a piece of ground on the company’s property, for the erection of a church to be used by the coloured people, who were then mainly living in that neighbourhood.” (Unkown, July 1913)

More telling is an extract from the S. Mary’s Parishioner of May 1907:

“…we have fostered and supported St Alban’s Church for the Cape Coloured people, who do not find welcome in the churches of their own parishes. They could enforce their rights as communicants, but, being a gentle, kindly and refined people, they prefer to come to a church where they are at home.” (Unknown, May 1907)

So the founding of St Albans was, in part, a solution to the racism of Anglican churches and their parishioners in Johannesburg.

The wood and iron church that Antonetta was baptised in has gone, and has been replaced by a very fine brick building designed by the diocesan architect, Frank Fleming. In 2012 the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation, with the assistance of the Mackenzie Foundation, performed necessary renovations and arranged for the pews from the Jewish orphanage at Villa Arcadia to be transferred to the church.

St Albans Church (The Heritage Portal)

Ferreirastown

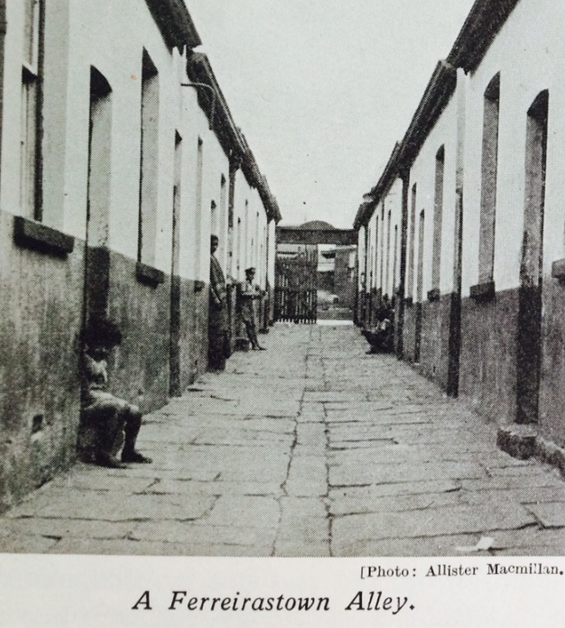

This extract from Allister Macmillan’s The Golden City, published in the 1930s, captures the atmosphere of the neighbourhood:

“Ferreirastown!

...with its conglomeration of dilapidated wood and iron dwellings housed on either side of narrow streets, some with broken wooden verandahs, and window panes plastered with brown paper or cheap chintz to keep out wind and rain.

Built chiefly in the form of blocks, narrow alleyways lead off into courtyards where on all sides are dingy and dirty looking rooms – the hovels of natives and coloureds. The air is thick and choking from the smoke of open coal buckets or braziers. Scraggy fowls in crudely constructed pens adorn many corners of these slum backyards; half-starved mongrels nose about refuse for something to eat; washing waves freely in the breeze under the fierce rays of the African sun, and meat is pegged on clothes lines to dry. In another corner may be found native women with gaily coloured dooks on their heads, cleaning and stamping native corn for beer…as they chant a low, monotonous work-song their bodies sway in rhythmical movement. Washerwomen, with piccanins strapped to their backs, ply their trade on the kerbstone, or squat lazily around on doorsteps and pavements, while innumerable children play about, ragged and thin. In this slum locatility may be seen all nationalities – “poor whites”, Syrians, Chinese, Indians, Malays, natives, and half castes…

In Ferreirastown squalor and poverty, sordidness and crime, reign supreme.” (Macmillan, Circa 1933)

A Ferreirastown alley in the 1930s. Source: Allister Macmillan’s The Golden City

Wedged between the mines to the south and industrial Newtown to the north, Ferreirastown was amongst Johanannesburg’s least desirable neighbourhoods and attracted a cosmopolitan population with few other alternatives.

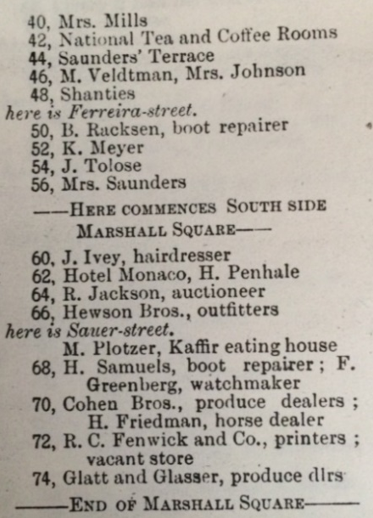

Saunders Terrace, the Henrys’ home on Antonetta’s record of baptism, was located at 44 Marshall Street, which in the late 1890s was wedged between Mrs Mills, the National Tea and Coffee Rooms, M Veldtman and Mrs Johnson, and shanties. Numbering on Marshall Street has since changed, but Saunders Terrace was on the block now occupied by the Anglo-American parkade, just west of the Mapungubwe Hotel.

An extract from the Rand Directory of 1897

A photo entitled “Natives under escort of S.A.M.R. move their dead from the scene of the fight at Ferreirastown to Marshall Square, March 8.” (dating back to 1922) shows Saunders Chambers in the background. This solid brick building is likely to be one and the same as Saunders Terrace. Its location placed it at the heart of some of the most violent episodes of the 1922 Strike, and it is no wonder that the young Antonetta vividly recalled those events.

Source: Museum Africa, from The Star

William George Henry and Kate Kathleen Henry

From the information that I have been able to source, it seems likely that William George Henry was the eldest son of Thomas and Antonetta Henry. No birth records have been found, but he was most probably born between 1889 and 1892. He appears to have had three brothers: Joseph Thomas, Benjamin Thomas and Sydney James. The earliest record traced, a baptism record of Joseph Thomas Henry dated June 1893, lists his father’s profession as Coachman and address as Irene Estate, Pretoria. By 1896 the family were living in Johannesburg, and in 1898 Thomas Henry is listed as a Coachman living at (and no doubt working for) Ferreira Mine.

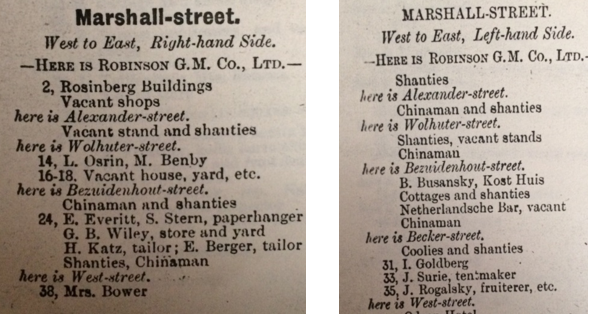

Two records of baptism for the children of William George list his wife as Kate Kathleen, his profession as Labourer (1912) and then Trimmer (1913), and their address as 25 Marshall Street (1912) and then Saunders Terrace (1913).

An extract of the Rand Directory for 1897 records the vicinity of 25 Marshall Street as follows:

Again, the impression is of a very poor, cosmopolitan neighbourhood. Today 25 Marshall Street lies under the Magistrate Court.

Sadly, no other information on Kate Kathleen Henry has come to light.

Jameli Dede

Father Ridout, who performed the baptism, no doubt felt that the exotic name of Antonetta’s godmother required an explanation, and confirmed that she was an Assyrian Christian. The Assyrian Church of the East (Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ܕܐܬܘܖ̈ܝܐ ʻĒdtā d-Madenḥā d-Ātorāyē), officially the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East (ʻEdtā Qaddīštā wa-Šlīḥāitā Qātolīqī d-Madenḥā d-Ātorāyē), is an Eastern Christian Church that follows traditional christology and ecclesiology of the historical Church of the East. It belongs to the eastern branch of Syriac Christianity. Its main spoken language is Syriac, dialect of Eastern Aramaic, and the majority of its adherents are ethnic Assyrians. It is officially headquartered in the city of Erbil in northern Iraq, and its original area also spreads into eastern Syria, south-eastern Turkey, and north-western Iran, corresponding to ancient Assyria. (Various, 2017). An internet search of the surname Dede reveals that it is commonly found in modern day Turkey. Interestingly, Macmillan refers to Assyrians in his description of Ferreirastown.

Meeting Arthur Frederick Cosslett

The next useful document is the marriage certificate of Antonetta Elizabeth Henry and Arthur Frederick Cosslett. It records the following:

- Date of Marriage: 13 July 1936.

- Full Names of Persons Married: Arthur Frederick Cosslett and Antonetta Elizabeth Henry.

- He is recorded as 28 years of age, born in the Cape Province, his profession Cabinet Maker, and his address 62 Newlands Mansions, Loveday Street, Johannesburg.

- She is recorded as 19 years old, born in the Transvaal, a Factory Hand by profession, residing at St George’s Chambers, Harrison Street, Johannesburg. Her father is recorded as having given consent for the marriage as she was underage.

- An address is written on the back of the marriage certificate: 25 Wilhelmina Street, Troyeville.

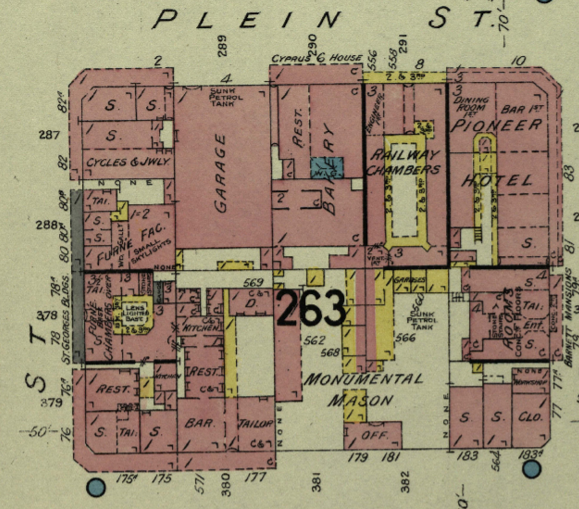

How Antonetta and Arthur came to meet is not known. I romantically imagine that it is at the Plaza Kinema, just down the road from Newlyn Mansions (the marriage certificate incorrectly spells it as Newlands Mansions). St. George’s Chambers was a mere two blocks away (on Harrison Street between Plein Street and Jeppe Street), so perhaps it was just a chance encounter on the street.

Newlyn Mansion in the foreground, with Plaza Kinema just beyond it, at about the time that Arthur Frederick Cosslett would have lived there. Source: Allister Macmillan, The Golden City.

The location of St. George’s Chambers (in the St. George’s Buildings), on Harrison Street between Plein Street and Jeppe Street. Source: Page 5, Insurance plan of Johannesburg: Transvaal Province, South Africa, January 1938, Chas. E. Goad, Ltd.

It seems likely that Antonetta Elizabeth was “coloured”. Was this known to Arthur? Did it matter to him? He had grown up in working class neighbourhoods in Cape Town – District Six, Woodstock and Salt River – where race remained a more fluid concept, so perhaps not. Had she transitioned from coloured to white society before she met him? I doubt that these questions will ever be answered, but it does provide an insight into the difference between segregationist South Africa pre-1948, and Apartheid South Africa after 1948. Antonetta and Arthur’s marriage certificate does not provide information on their race. A mere thirteen years later, The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 (an Apartheid law in South Africa that prohibited marriages between "Europeans" and "non-Europeans", and among the first pieces of apartheid legislation to be passed following the National Party's rise to power), would require this to be recorded. Following soon after, in 1950, the Population Registration Act was created to provide definitions of “race” based on physical appearance, as well as general acceptance and “repute”. Once all these factors had been taken into account and established, the act made provision for the carrying of identity cards in which the race of a person would be clearly marked. (Oakes, 2017)

By 1965, when Arthur and Antonetta bought their home in Park Street, Belgravia, she is recorded as White on the title deed.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.