Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

As a callow teenager, Joseph Kirkman left an indelible mark on the annals of early Natal history. He is remembered for his efforts in assisting the American missionaries to establish a bridgehead in Zululand and his subsequent heroic exploits in assisting the evacuation of those missionaries following the turbulence consequent on the Retief massacre. He will also be remembered for having the expedient foresight to commit his observations of those calamitous happenings to paper, which provided unique insights and enabled historians to interpret some of the causes and consequences of those events more precisely. Regrettably, his records disappeared before qualified historians could carry out adequate studies.

Joseph was a scion of the 1820 Settlers. The young twin sons of 1820 Settler John Kirkman, John and Joseph, were orphaned in the early months of the 6th Frontier War. Their father and stepmother succumbed to the rigours of escaping the sacking of the Rev John Brownlee’s Mission station on the Buffalo River (the site of present-day King Williamstown), where they had taken refuge. With the missionary’s party, they experienced a harrowing flight to Graham’s Town, fraught with protracted terror and hardship.

Shortly after these tragic events, three young children of the folk involved were placed in the employ of parties of American missionaries who were destined for the hinterland and for Port Natal. These missionaries had been sent to South Africa by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, of Boston, Massachusetts, as a result of advice sent to the Board by Dr John Philip of the London Mission Society in Cape Town.

The engagement of the lads was arranged through the Rev John Brownlee’s contact with the American missionaries, more specifically with Aldin Grout. The missionaries Lindley, Venables and Wilson were originally sent to minister to the Matabele, and Adams, Grout and Champion to the Zulus. The mission to the Matabele was a failure from the start, being met with indifference and even covert hostility by Mzilikazi and his people. When the Boer Commandos attacked Mosega (present day Zeerust) in January 1837, the Americans wisely decided to clear out, in order to avoid retaliation on themselves. After a circuitous trek via Thaba Nchu and Graham's Town and experiencing many vicissitudes, they joined their co-workers in Natal.

One marvels at the fact that Joseph Kirkman was not fully 14 when, in the company of James and Charles Brownlee, he went to the London Mission Society station at Bethelsdorp near Port Elizabeth, to take on the job of guide, wagon driver, general assistant and interpreter for the newly-arrived missionaries, and ventured into the unknown. Their knowledge of isiXhosa would have enabled them to cope with isiZulu with ease. James Brownlee (who was killed in the war of 1850) accompanied Lindley, Venables and Wilson to the hinterland, while young Joseph Kirkman and Charles Brownlee accompanied the Champion and Grout parties to Port Natal. All were under 17 at the time.

With his friend and fellow-interpreter Charles Brownlee, Joseph trekked by wagon from Bethelsdorp on 21 March 1836, conducting the missionaries Adams and Grout to Port Natal, and also conveying the spouses of Adams and Champion. The Rev Champion was already at the Umlazi mission in Port Natal, having sailed there three months previously to establish a bridgehead. The wagons reached King William’s Town on 4 April, where the party received encouragement from Sir Harry Smith. On 9 April they reached Butterworth Mission, and arrived at the Umlazi Mission in Natal on 21 May, after a wagon trek lasting two months. They stayed with the Champions at Umlazi for a few months, and on 30 August Charles and Joseph conducted the Champions and Grout into Zululand, with two wagons, to launch their missionary work.

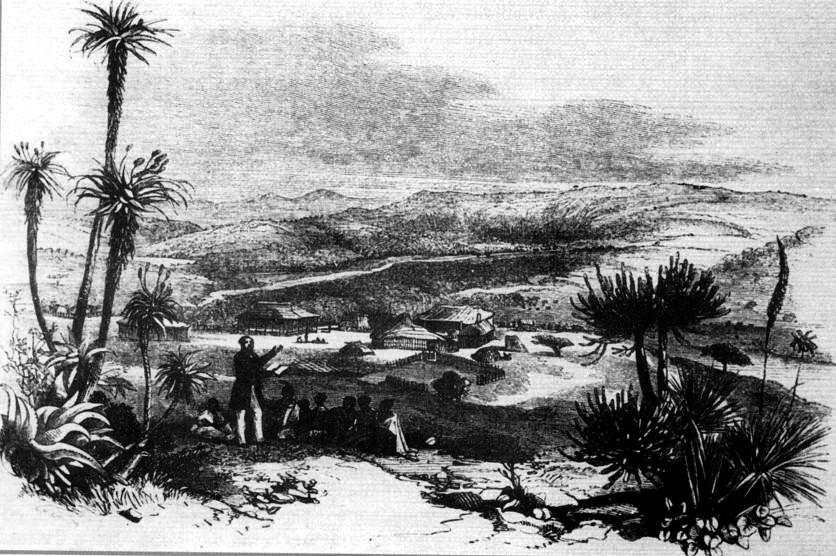

Rev George Champion delivering an open-air sermon at the Ginani Mission Station

In July 1836, Grout and Champion visited Dingane, who subsequently gave them permission to carry on missionary work in the Hlomendlini, the territory lying between the Tugela and the Amatikulu Rivers. In September they established their mission station there, in a fertile well-watered valley. They chose a site in a bend of the Msunduzi River near its confluence with its tributary the Winya at a place they called Ginani. The name was derived from the isiZulu word nGinani, meaning “Lo! I am with you”. This site, between the present-day town of Mandini and the hamlet of Nyoni, lies near the old Indulindi road and 500m west of the main road to Gingindhlovu. It is situated about 13km north of the Tugela and about 14.5km from the ocean.

The history of Ginani is a moving story of the persistent struggle of these devoted evangelists against the equally persistent opposition of the local tribe, especially in the person of Kokela, the Chief of Nyanduna. In addition, the mission station was exposed to the vagaries of unrest that affected Zululand during 1837 and 1838, because besides Nyandhlana there were two other large Zulu villages in the Hlomendlini, which supplied Dingane with his best impis: Hlomendlini Omhlope, the kraal of the experienced White-shield regiment commanded by the famous leader Nongalaza, and Hlomendlini Omnyama, the kraal of the Black-shield regiment. The effects of every political and military event were felt at Ginani.

Dr Wilson and Venables, after having abandoned the so-called “Inland Mission”, established a mission station at the old Zulu military post Hlangezwa on the Umhlatusi River, about 30 miles south-east of Dingane’s kraal at Umgungundhlovu, with Charles Brownlee as interpreter. Lindley was on the Illovo river at Imfumi, and Adams, a physician not yet ordained as a missionary, was at Umlazi.

Dingane’s attitude towards the missionaries changed rapidly with the appearance of the Voortrekkers in Natal. The number of Zulu converts at Ginani suddenly dropped from an estimated 100 to a meagre four. All trade with the missionaries had stopped by the end of January 1838, and there were no longer any children in the school.

The conflict between Dingane and the Voortrekkers is too well known and adequately documented for any further repetition here. However, very importantly, young Joseph Kirkman, as a close witness to many of these events and their tragic consequences, kept a “diary”, or more accuratey a chronicle of some sort, recording those momentous happenings. Unfortunately, and this is the crux of this narrative, his writings seemed to disappear after an all too brief scrutiny by some notable historians, and they remain missing to the very present. Sadly, the fate of the original (or originals), as well as other of Joseph’s documents, has remained a mystery for all these years

Either in diary or other form, Joseph committed his experiences to writing, and was known to have sent copies to members of his family in the Colony. The fragments of his writings that were fortuitously viewed by historians, have become renowned for giving historians deeper insight into the circumstances leading up to and surrounding the massacre of Piet Retief and his party by Dingane, and the chain of events triggered by that atrocity.

In an article written in 1956, (a typescript of which is filed with the “Kirkman Papers” in the Killie Campbell collection), the expert historian on the Zulus, Natalian H. C. Lugg, wrote that:

Joseph Kirkman kept a diary or diaries, and one of these came into the possession of Sir George Cory, the historian, and I have before me a copied extract from this little book quoted in an address by Sir George at a meeting presented by the late Sir Edgar Walton in London on the 16th December. [Note: year not stated, but probably ca 1922]. In it Joseph narrates at considerable length his adventures and experiences whilst in Zululand during that critical and dangerous period...

Some years ago I was privileged to see a little note book in Kirkman’s handwriting in the possession of the late Mrs Kirkman, widow of the late S. E. Kirkman, a magistrate who died whilst stationed in Durban in 1919 - 20. He was probably a grandson of Joseph’s. As far as I can remember it contained information very similar to what I have before me, but as this was described as a fragment” by Cory because of its abrupt ending, this book may have been connected with the one in Cory’s possession.

Kirkman’s account, told very lucidly, must be regarded as a remarkable achievement as his education must have been of the most elementary kind. Dr Killie Campbell is now on the trail of this diary, and I feel sure she would greatly appreciate any assistance or information leading to its recovery.

The deceased magistrate to whom Lugg referred was Sidney Edwin Kirkman who was Joseph’s youngest son (not his grandson). He was born in about 1869 and died in 1923. The “late Mrs Kirkman” to whom Lugg also referred was Sidney Edwin’s widow Frances Sarah Kirkman née Cundill..

An article appearing in The Star in October 1956 was written in the same vein:

Does anyone know where the Kirkman “diary” is? It is a small hard-covered notebook, worn with age, and it carries the story that Joseph Kirkman told of his experience with Dingane during the blood-letting days in Natal from 1836 to 1840.

Dr Killie Campbell, who houses a valuable collection of Nataliana in her home in Marriott Road, and Mr H. C. Lugg, former Chief Native Commissioner for Natal and a well-known authority on the Zulus, are both searching for it. Because of its great historical value and importance, and the light it throws on such incidents as the Retief massacre, they are keen to have the diary under proper protection.

Dr Campbell saw the diary about 25 years ago [Note: about 1931] when a descendant of Joseph Kirkman showed it to her. She warned the owner of its value but has lost track of it since.

Dr Campbell’s interest in Joseph’s writings were well documented in Norman Herd’s book Killie’s Africa: The Achievements of Dr Killie Campbell:

Long before the Second World War, Killie had become recognised as a conscientious collector of a wealth of documentary material which she describes as part of the national heritage and should not remain permanently in private ownership. Among the items of this character which fell into her receptive hands was the diary of Joseph Kirkman, a stripling of some 15 years attached to the American Missionary, George Champion, at his station in Zululand a few miles north of the Thukela.

Kirkman’s diary with its particularly significant references to the events of 1837 and 1838 was brought to Muckleneuk (Killie’s Durban home) by a woman whom Killie fails to identify save that she was a descendant of the diarist. She was without a doubt the person who had copied out a portion of the text for Sir George Cory’s benefit some years previously. Cory, who was then editing the missionary Owen’s diary for publication by the Van Riebeek Society, was quick to grasp the importance of this supplementary material.

Killie, herself, was enthralled with it. It was her bad luck that the document was whipped away before she could arrange for its entire contents to be reproduced on a typewriter.

Kirkman, despite his youth, was an acute observer of historical events, with a capacity to assess their significance. Since it was part of his duties to interpret, for Champion’s benefit, the information brought to the mission by Dingane’s emissaries, he knew very well what was going on. He received an early hint of the Monarch’s alleged intention to murder Piet Retief during the latter’s first visit to emGungundhlovu in 1837 - a prospect of which the Voortrekker leader was said to be blissfully ignorant.

When Retief announced his plan to call on Dingane again early in the following year, Champion signified alarm. He “told Mr Retief that he had now had two years’ practical knowledge of the King and as sure as Mr Retief paid a second visit to Dingaan, accompanied by sixty or more men, so sure would the King have them all put to death”.

Kirkman’s knowledge of Dingane’s original plot to rid himself of the Boers is explained by the fact that the amaThozi clan whose chief, Sigwebana (also a son of Senzangakhona) had been instructed to organise the execution, were settled on land but a short distance from the mission. Sigwebana was to accost the Boer party marching west to recover the Zulu cattle from Sikonyela, invite them to stop for refreshment, and put them to death. [Note: Senzangakhona was the father of Shaka]

The chief decided, however, not to carry out the plan and fled to Southern Natal when his frustrated monarch set upon his tribe, killing several hundred and pursuing others to their death in the river. Kirkman recorded that he saved the lives of a black woman and an infant who were taken out of the mission house, stunned by blows and left to the attention of the vultures.

His chronicle of events offers well-defined clues to the relationship between Dingane and the missionaries and other whites. It serves to disarm any suspicion there may have been that (Dingane) was either instigated or influenced by anyone in Natal to commit the horrible murder of February 6th, 1838.

Dingane was well aware that the missionaries deplored his savage deed and he was irritated by their censure. On the other hand, he was determined not to molest them unless they provoked him too far. This somewhat conciliatory note is confirmed by a note in the diary which commended itself to Killie for its historical significance and graphic quality of the writing. On the Sabbath day (February 11) the mission staff and two guests were seated at dinner when a shadow darkened the doorway. Everyone at the table turned to look. There stood a Zulu warrior in “full tails and fully armed, making his obeisance to Mr Champion. He stated that he had been sent by Dingaan to request Mr Champion not to be alarmed that he, the King, had put Retief and all the Boers to death. The missionary had Dingane’s full permission to leave and go to Natal or remain, should he wish to do so. If he stayed he would enjoy royal protection from any molestation....”

Because of the precipitate departure of her visitor with her priceless document, Killie was deprived of a complete picture of those tragic times, as drawn by a perceptive youth positioned so close to the centre of events. She was left with a photograph of the diarist and a couple of fragments from the little book, dictated to her staff while skimming through its pages, and Harry Lugg joined her in an effort to locate the document but without success.

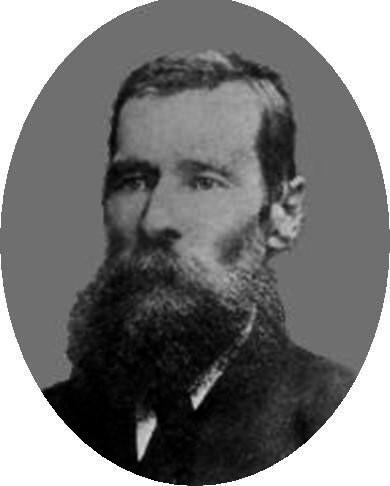

In her collection, however, Dr Campbell has a typewritten copy of a story that Kirkman had obviously dictated to an amanuensis, and a photograph of Kirkman himself, obtained from the relative.

Joseph Kirkman in later years (Killie Campbell Africana Museum)

Many copies of the manuscript, or part of it, seem to have been made over time, some in cursive before general use of the typewriter, and others typed in later years. Not one copy agrees with the others in all respects; the spelling of place and personal names varies hugely, and punctuation and syntax have been modified to suit the whims of the scribes and their target readership.

The African Studies section of the Johannesburg Public Library (The “J. P. L. Strange Collection”), has a typed transcription of The Life of Mr Joseph Kirkman in Zululand from 1836 - 1840, which they only make available to post-graduate students and research workers. The University of Cape Town Library also has a “Joseph Kirkman collection”, which they summarise as a “typed transcription; Joseph Kirkman, interpreter to G. Champion, American Board of Missionaries in Natal, with personal reminiscences”. This is another copy or transcription of the same document.

Joseph’s grandson Sir Reginald Blankenberg, donated a copy of the article A Fragment from the Past (Anna Howarth’s transcription of Joseph’s narrative) to the Natal Archives. Guy Butler used abbreviated excerpts and modified the text considerably for popular consumption in his book When Boys were Men, which incidentally also contains a chapter on Charles Brownlee, dealing with the tragic events at the Buffalo Mission in 1834, involving Joseph’s father, the Settler John Kirkman.

The celebrated historian Sir George Cory produced his own version in his book The Diary of the Rev Francis Owen, MA, Missionary with Dingaan in 1837 - 1838, together with extracts from the writings of the interpreters in Zulu, Messrs Hulley and Kirkman. This version is probably the closest to the original text, even though it has also been modified here and there. But at least it adheres more closely to the quaint, almost phonetic style of personal and place name spelling, and unconventional punctuation.

The historical writer Thelma Gutsche, in an article on the author Anna Howarth that she published in the Eastern Province Herald in 1961, dealt with Joseph’s writings and stated that: “The famous historian, Sir George Cory, obtained a copy of this record “from an old lady at Port Elizabeth” and published it in conjunction with the diary of the missionary Owen who was at Dingaan’s kraal at the time.” Thelma Gutsche asserted that “The old lady at Port Elizabeth was Anna Howarth”. It is certain that Anna Howarth had a copy of Joseph’s writings, which she probably acquired through her association with the Karoo family of Joseph’s twin brother John, with whom she lived for 40 years of her life.

A descendant of twin John lodged a typed copy of the manuscript in the MacGregor Museum in Kimberley. The writer has in his possession, acquired through family the family hand-me-down system, a handwritten manuscript in Anna Howarth’s own hand, the very manuscript that she submitted for publication in The State in December 1910, under the title A fragment from the past.

Several roneoed copies of a typed transcription of Joseph’s record, which came into the possession of various members of the Kirkman family, displayed this inscription below the title on the cover page: The original manuscript is now in the possession of E. B. Kirkman, a grandson of Joseph Kirkman, and a further note claimed copyright. This was Esmond Bruce Kirkman, who was a son of the late magistrate Sidney Edwin Kirkman whose wife was quoted by Lugg as being the custodian of the “diary”.

For many years the writer pursued several cold leads in a quest to find the missing manuscript(s). The paramount, tantalising question was what became of the purported original manuscript that was in Bruce Kirkman’s possession? Bruce died in Port Shepstone in 1970 in rather parlous circumstances. He had two sons, Richard Ian and Edward Alen. Both were already deceased at the time of the search, and any possible knowledge they may have had of the manuscript had gone with them. Follow-up with other descendants and relatives drew a disappointing blank.

However, in 1958 a singular event occurred which could conceivably allow the mystery of Joseph’s missing “diary” to be put rest. This event, described below, was discovered quite fortuitously while idly browsing through unlikely files in the National Archives, in pursuit of genealogical detail regarding Joseph Kirkman’s descendants.

During the late 1950s Bruce Kirkman was residing at Judith’s Farm in Argyle Avenue in Craighall Park, Johannesburg. This property was part of a larger tract of land known as River Bank Farms, and Bruce hired this dwelling from the joint owners, Sydney MacKenzie Barnett Potter and his wife Ursula.

Bruce Kirkman’s hired cottage on Judith’s farm

Barnett Potter emigrated to South Africa from London in the 1930s for health reasons, having suffered gas damage to his lungs during World War I. He had seen action as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corp. In South Africa he achieved acclaim and some notoriety as a journalist and broadcaster, his particular forte being in the spheres of finance and politics. Although he left the country in 1950 due to his antipathy to the rise of the Nationalist government, he did return in later years. He was the author of the best-selling book in South Africa, The Fault, Black Man……, a book which was, for obvious reasons, removed from library shelves post 1994.

In late 1958 the Potters, then residing in London, arranged for a team of thatchers to carry out renovations to the thatched roof of their tenant’s cottage on Judith’s Farm. In the process, the workmen injudiciously stacked bundles of thatching grass against the upper chimney of a slow combustion stove in the kitchen below. Predictably, the grass ignited and the fire spread, resulting in Bruce losing practically all his possessions in the ensuing conflagration.

In due course Bruce instituted a claim against the Potters, on the grounds that the catastrophe had been caused by their appointed agents, for whose actions, Bruce alleged, they (the Potters) should be held accountable. The case file makes absorbing reading, and reveals interesting drawn-out exchanges between the legal representatives of the opposing parties. This was spread over a lengthy period, with the Potters seeming to introduce, piecemeal, every conceivable stalling tactic, and demanding additional inconsequential detail at every turn. Bruce’s lengthy and minutely itemised inventory of articles lost in the blaze included clothing, bedding, curtains, crockery and glasses, furniture and every other household article imaginable.

But most importantly, Bruce was distressed about the loss of over 500 precious books, many of them claimed to be prized first editions. The detailed list of titles that he submitted covered a range of various technical works, books on gardening, fishing, travel, photography, fauna and flora, autobiographies, poetry and philosophy as well as various items of africana. Many were purported to have been brought from the U.K. and were out of print. Occupying pride of place at the very top of his list of titles, we find what must have been his most treasured possessions, namely the Kirkman Family Bible and the Diary.

With a reasonable degree of certitude it can therefore be construed that Joseph Kirkman’s elusive “diary”, so ardently sought by Killie Campbell, H. C. Lugg and other Natal historians, and so jealously guarded by Bruce, went up in smoke and ended up amongst the ashes in the burned-out ruins of the cottage on Judith’s Farm.

Sadly, the archived records of the legal proceedings do not intelligently reflect the final outcome of Bruce’s legal claim. Whatever may have transpired in the courtroom lies concealed in approximately 150 pages of now outmoded and indecipherable shorthand text.

Peter Kirkman was born in the rural Northern Transvaal (now Limpopo), educated in Johannesburg. He qualified as a Forester at the Saasveld College for Foresters near George, and spent his whole working life in the forestry sphere. A consuming interest in genealogy and family history culminated in the publication of his book “From Manchester to Albany and Beyond” which deals with the genealogy of his 1820 Settler forebears and their descendants.. This book was voted by the Genealogical Society of South Africa as the Outstanding Genealogical Publication for 2014.

Now retired and living in Hilton, he continues to busy himself as an amateur genealogist and family history “sniffler”.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.