Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In Fordsburg, passersby hurry through a nondescript market square bordered by Albertina Sisulu, Dolly Radebe, Mint and Central Roads, quite unaware it marks the final stronghold of armed strikers during the 1922 Rand Revolt.

Known as the 1922 Miners’ Strike, Rand Revolt or even Red Revolt, occurring merely five years after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, it remains the greatest violent political upheaval on the Witwatersrand (Rand).

Although the Rand has changed almost beyond recognition, many of the historical sites exist, to provide a glimpse of that seismic event. Some of these sites will be disclosed in a future article.

Accounts vary, but the Report of the Martial Law Inquiry Judicial Committee reported the fatalities of the strike and subsequent armed revolt to comprise 43 soldiers, 29 policemen, 11 revolutionaries, 28 suspected revolutionaries and 42 civilians.

A further 133 soldiers, 86 policemen, 45 revolutionaries, 73 suspected revolutionaries and 197 civilians were wounded.

After the revolt was quelled, 4 692 men, 62 women and 4 children were detained for questioning. Eight hundred and fifty-three people, including 9 women were charged with various contraventions, from murder and treason to minor infringements of the martial law regulations.

Ten unions established the Transvaal Strike Legal Defence Committee, to raise funds for legal representation to those appearing in court. Forty-six people were charged with murder and 18 were sentenced to death. Only four namely, C. C Stassen, S. A. (Taffy) Long, Herbert K. Hull and David Lewis were executed between 5 October and 17 November 1922. Vehement public protests against their hanging forced the government to backtrack and instead recommend clemency to the Governor General, for the remaining fourteen.

The severe post war economic recession lasting from 1920 until the beginning of 1922, underly the reasons for the strike. The declining gold price from £6,37 to £5,20 per fine ounce, placing marginal gold mines at risk, contributed to the strike.

The Chamber of Mines (Chamber) tabled three proposals for the gold mine wage negotiations. Firstly, to reduce wages of mine workers because the cost of living was decreasing. Secondly, to change underground working arrangements to reduce costs; and thirdly to modify the Status Quo Agreement, to lower the ratio of White to Black employees.

E. J. Way, President of the Institute of Engineers, in July 1921 said 50% of White mine workers could be replaced by skilled Black employees, thereby saving £1 000 000 annual. He said the gradual removal of the ‘sentimental colour bar’ would also bring lasting prosperity to the mining industry, through the restarting of marginal gold mines.

The South African Industrial Federation (SAIF) representing the unions, rejected the Chamber’s proposals. It argued it was unfair to reduce all wages to a lower rate which the marginal mines could afford, since many gold mines remained profitable.

The colour bar dates from the 1911 Mines and Works Act, when certain occupations were reserved for Whites. To ensure the gold mines operated without disruption during wartime, the Chamber and the SAIF implemented the Status Quo Agreement in 1918. It prohibited the replacement of Whites by Blacks in occupations traditionally performed by White employees. By 1920, thirty-two occupations employing 7 000 people were reserved for Whites, based on a ratio of one White employee for every 8.2 Black employees. The SAIF feared 4 000 Whites would lose their jobs if this Agreement was modified, although the Chamber maintained it would only affect about two thousand.

The Transvaal coal mines were also in dire straits. During the First World War they prospered because of increased exports. By 1921, exports had dried up because of cheaper British coal. Hence, the Chamber proposed to reduce coal miners’ wages by 5s per day.

Although the Chamber’s arguments were valid, so were the fears of White mine workers. Thousands of poorer Afrikaners had drifted from farms to the mines and because of the recession there was little alternative employment. The Rand trade unions had been formed by British immigrant workers specifically to protect Whites from competing against cheaper Black labour.

Initially refusing to interfere, the government felt the Chamber and SAIF should themselves resolve the matter.

Nevertheless, monitoring the coal mining negotiations the government cautioned the SAIF in December 1921, that it would ensure essential public services continued during a strike. This specifically applied to the Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Company, the main electricity provider on the Rand. Without electricity, the deeper underground levels of gold mines would flood causing lasting damage. The SAIF, unsurprisingly felt government was siding with the mine owners.

On 21 December 1921, Patrick Duncan Minister of Foreign Affairs, met the SAIF to discuss the coal dispute. The SAIF proposed arbitration, which Duncan conveyed to the Chamber. The Chamber rejected this, citing the precarious state of coal mines.

The SAIF convinced the Chamber intended to force matters, supported the coal miners’ strike, commencing 1 January 1922. On that day, all coal mines in the Eastern Transvaal and along the Vaal River ceased production.

A strike on the gold mines also seemed imminent when the Chamber informed the SAIF on 28 December 1921, that it still maintained its three proposals.

On the same day, the Victoria Falls Power and Transvaal Company (VFP) informed the SAIF, further negotiations would be fruitless as it intended to freeze existing wage rates.

The affected unions formed an Augmented Executive to co-ordinate this pending strike. All nine unions on the Augmented Executive supported the strike on the gold mines and at the VFP, with 12 192 workers voting in favour and 1 336 against, from a White workforce of just over 20 000.

The strike started on 10 January 1922, halting all gold mining activities, from Springs in the east to Randfontein in the west, causing 20 000 White and 180 000 Black mine workers to stand idle. The power stations of the Victoria Falls Power Company, supplying electricity to the gold mines and municipalities, excluding Johannesburg, also shut down for a while. Initially, only the Rosherville Power Station, situated between Johannesburg and Germiston was allowed to operate on a reduced basis. It provided just enough electricity for underground pumping and lighting operations. Johannesburg, although having its own power station, remained vulnerable because coal was provided by strike affected mines.

Rosherville Generating Station with its water reservoir (Eskom Heritage)

The government tried hard to get the Chamber and SAIF to resume negotiations. Several meetings and even a lengthy tri-lateral conference chaired by Justice Curlewis (14 - 27 February) took place. The meetings confirmed the Status Quo Agreement remained the stumbling block to resolving the strike. Demonstrating against the proposed modification of this Agreement, strikers coined the bizarre slogan, ‘Workers of the world fight and unite for a White South Africa!’. This slogan placed the socialists in a difficult position. While not supporting it, they hesitated to repudiate it for fear of alienating Afrikaans mine workers.

As the strike continued into February 1922, the situation became ominous. Striker commandos were formed, supposedly to maintain order, but seemingly more concerned with intimidating scab labour. A rumour that shopkeepers were no longer granting credit to strikers caused widespread concern. Many strikers relied on emergency relief because they lacked savings and the duration of the strike. Strikers also marched on Crown Mines in an aggressive mood, warning officials of the consequences if they continued working the mine.

Around this time, a leadership vacuum developed between the Augmented Executive and the Central Strikers’ Committee, responsible for coordinating activities of all local striker committees. It gave opportunity to extremists of the militant but fringe mine workers body, the Council of Action, to take over the strike for their own purposes.

Some of the Marxist members of the Council of Action were; Percy Fisher, William Wordingham, Ernest Shaw, F. W. Pate, A. McDermid, D. McPhail and Henry Spendiff.

At a Johannesburg meeting on 7 February, Fisher warned strikers against any local meetings to discuss terms with employers. He said the first man to return to work should be smashed until not a breath was left in his body.

The following day to neutralise the growing influence of the Council of Action, the police arrested Fisher, Spendiff, Shaw and Wordingham at the Trades Hall in Rissik Street, for inciting public violence. The magistrate refused to release them on bail ordering their remaining in custody.

Government aggravated the tense situation by announcing on 11 February that Police would protect those strikers returning to work. By mid-February, there were strike pickets at every mine shaft on the Rand.

The Council of Action members upon their release from custody on 22 February, immediately preached violent action. On 24 February, Shaw told a crowd all great political and social changes had only been achieved through militant action.

The first group of Special Police, the ‘Blues’ assumed duty on Monday 27 February. This force of about 700 armed and paid personnel protected the mines, relieving the regular police for other pressing duties.

The first serious clash between the Police and the strike commandos happened on the same day. Captain John Fulford, District Police Chief of the Eastern Rand, saw 50 mounted members of the Boksburg and Driefontein Hill striker commandos near the Witwatersrand Deep Goldmine, between Germiston and Boksburg. After the strikers delayed a train at the Angelo Crossing, the police overtook them and ordered a dispersal. When the strikers refused, a scuffle broke out with three policemen and eight strikers sustaining injuries. More than 20 strikers were arrested and detained in the Boksburg prison.

Boksburg Prison in Commissioner Street not far from where Captain Fulford fired on the strikers (SJ De Klerk)

The next day 28 February, Captain Fulford observed about 250 strikers marching from Boksburg North to the Boksburg prison in Commissioner Street, supposedly to sing the Red Flag to their imprisoned comrades. Fulford, convinced they intended to free the prisoners, twice ordered the crowd to disperse. When they refused, the police fired into the crowd killing three strikers.

Their funeral procession at Boksburg on 2 March stretched for three kilometers, while at the Union Grounds in Johannesburg, 5 000 people gravely listened to the mournful sounds of the Last Post.

Now the strike reached a turning point, paving the way for the subsequent collapse of law and order. Henceforth, striker commandos attacked not only scab workers, but also police contingents.

Concerned at the escalating violence, the Augmented Executive wrote to the Chamber on 4 March, proposing an urgent meeting to discuss terms to resolve the strike. Unfortunately, the Chamber replied the same day in a very tactless letter.

It rejected the meeting request and replied it would no longer recognise the SAIF for any purpose, claiming it no longer represented the bulk of employees in the gold and coal industries. Presumably, the Chamber felt it had the upper hand and a forceful response would rapidly scupper the strike. Unfortunately, it only aided the Council of Action to hijack the strike and turn it into an armed revolt.

The Augmented Executive met throughout the night to discuss the Chamber’s response. The next morning, it announced a strikers’ ballot would be held to decide whether the strike should continue, or not.

The Council of Action dead set against this ballot, decided to take over the strike with the backing of the striker commandos. The Council immediately set up a Committee of Action to take quick decisions. Andrews, Fisher, Spendiff, Mason, Wordingham and Shaw, known for their radical views, were appointed to this Committee. Its immediate plan was to thwart the ballot and force a general strike across the Rand.

On 5 March, the Central Strikers Committee called a meeting of the district striker committees. Bill Andrews representing the Council of Action eloquently argued against the ballot and for the start of a general strike, as the only means of defeating the employers. His proposals were soon adopted.

On 6 March, thousands of strikers congregated at the Rissik Street Trades Hall where delegates from the union executives were discussing the strike situation and the proposed ballot. The striker commandos gathered outside, while the Committee of Action agitated them to a fever pitch. In the late afternoon, Joe Thompson, Acting President of the SAIF, announced the decision to embark on a general strike, commencing immediately and to be coordinated by a Council of Five.

Strikers congregating at the Rissik Street Trades Hall (Wikipedia)

The Council of Five shortly abdicated, unconditionally handing over authority to the Committee of Action.

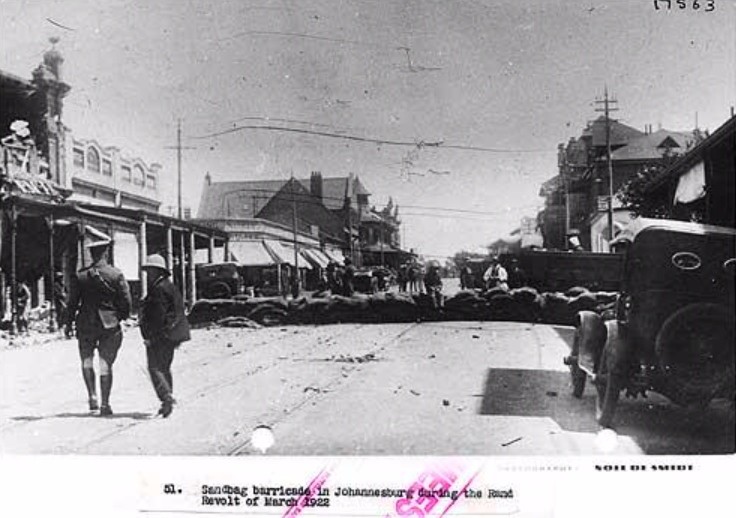

The striker commandos now started arming themselves. Police reports described strikers armed with bicycle chains, old swords and bayonets, poles barbed with spikes and a variety of firearms. The strikers also intensified their activities, marching everywhere, recruiting more workers to the strike and intimidating non-strikers.

Overnight, striker violence seemed to spread across the Rand.

On 7 March, strikers stopped railway employees at the Braamfontein, Kazerne, Johannesburg, Germiston and other stations from working. When the police arrived outside the New Law Courts at Von Brandis Square to control a crowd of several thousands, they were stoned and fired upon. Later the day, strikers were seen attacking Africans in Vrededorp. Lieutenant Colonel Godley Deputy Commissioner of Police for the Witwatersrand believed the racial attacks were instigated by the Council of Action to embarrass the authorities and intimidate citizens.

On Wednesday 8 March, the railway line near Driefontein on the East Rand was sabotaged and a train and a ganger fired upon. In the afternoon reports of fighting between strikers and Africans in Ferreirastown were received. On the Primrose Mine further racial violence occurred. It became clear the police were no longer able to control the strike, which was now rapidly developing into an armed revolt.

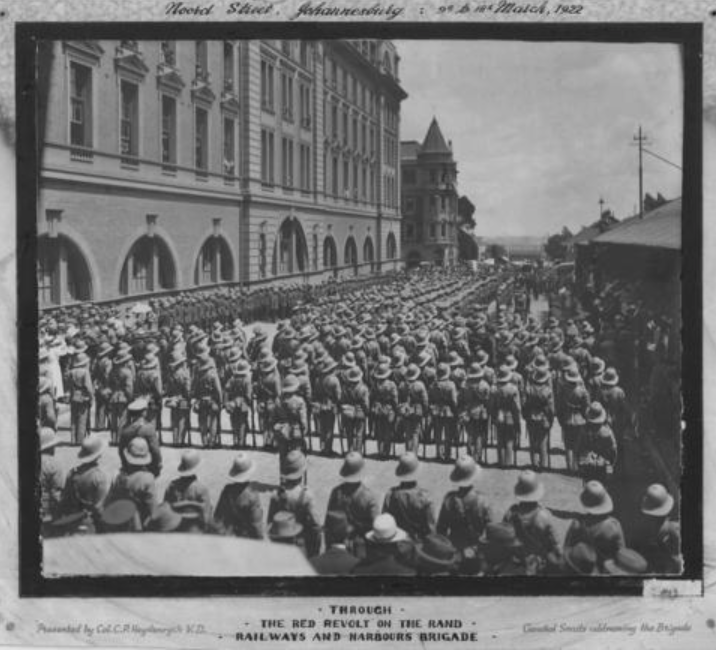

The government for political reasons hesitant to declare martial law, as a precautionary measure requested the Governor-General to issue a proclamation on 9 March, calling up several Active Citizen Force (ACF) units. They were the Transvaal Horse Artillery, Transvaal Scottish, Imperial Light Horse, Pretoria Regiment, two companies of the 1st Infantry Battalion – Railways and Harbours Brigade and the 1st Field Ambulance – SA Medical Corps.

The Railways and Harbours Brigade

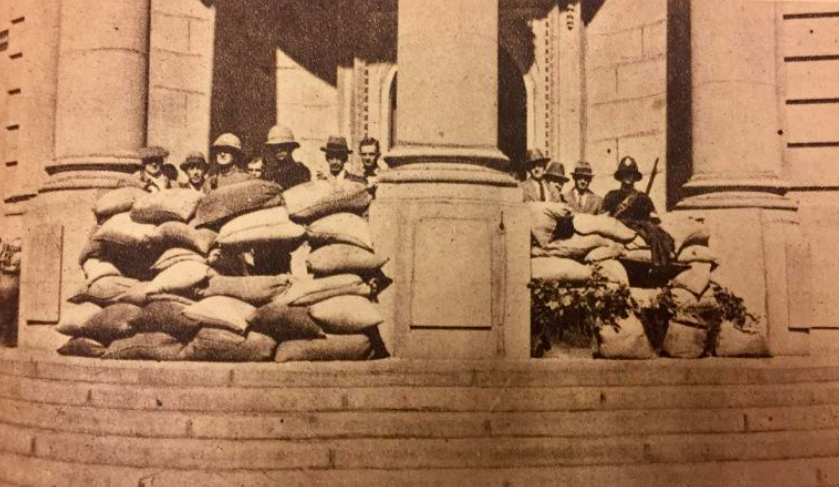

The same day, the police obtained alarming information. Striker commandos planned to attack the Newlands, Fordsburg and Auckland Park Police Stations, as well as the Cottesloe Camp of the Special Police. Following these attacks, the striker commandos intended to march onto the Town Hall to take full control of the city.

Three troops of police were accordingly deployed to the south of the Brixton Ridge overlooking the main road between Brixton and Newlands, with a fourth troop on a smaller ridge overlooking the Auckland Park Race Course. Although surrounded, they managed to prevent the various striker commandos from linking up and marching onto the City.

The Brixton Ridge, a long-curved spine of low hills, spreads to the west of the city and flattens out in the south. Commanding this ridge was vital to the strikers to fend off attacks against their western stronghold from the north or north-east. From the ridge they would also be able to support the planned advance on their left and right flanks.

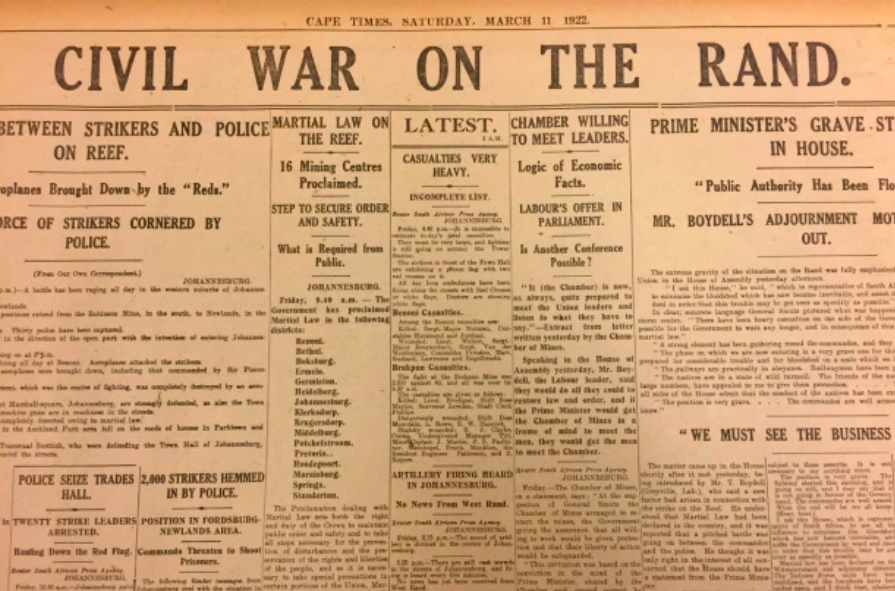

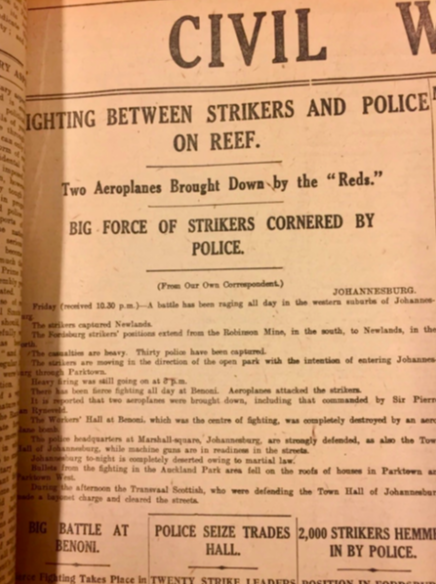

On Friday 10 March 1922, ‘Black Friday’ as it was subsequently called, fighting occurred from Newlands to Springs, excluding only Germiston and the West Rand. For a while it seemed the strikers’ revolt would carry the day.

Cape Times article

In the early hours, striker commandos attacked the Newlands Police Station and at 07h50 the beleaguered police surrendered.

The Police Charge Office at Fordsburg and the barracks about 400 meters distant, were both attacked. Lieutenant McDonnel and nine men held out at the Charge Office until about 18h00, when their ammunition ran out. They then fled to the nearby barracks, where the strikers were held off until the end of the revolt. One of the fleeing constables was assisted by a shopkeeper called Pieter Marais. The following day Marais was seized by the strikers, tried as a police spy, sentenced to death and summarily shot against one of the walls of his shop. Marais prior to dying a few hours later, uttered he was shot by a striker called Long.

Family Grave site of Marais Family, where Pieter Marais was buried in the Brixton Cemetery (SJ de Klerk)

At 09h00 the same day, the government finally proclaimed martial law on the Rand and adjoining districts. Simultaneously, additional ACF units and 26 burgher commandos were called up. The ACF units were the Durban Light Infantry, Railways and Harbours Brigade (Headquarters and two infantry battalions), Witwatersrand Rifles, Rand Light Infantry, two units of the SA Service Corps, and the 1st Sanitation Section – SA Medical Corps. The burgher commandos were drawn from the Eastern and Western Transvaal and Pretoria to Middelburg Military Districts.

General Beves was placed in charge of the Johannesburg area. Generals J. van Deventer and Coen Brits were to lead the offensive on the East Rand, while Colonel Hussey was given charge of the West Rand, where fortunately the revolt had largely fizzled out.

Notified of martial law, a strong police contingent surprised and arrested several delegates of the Council of Action at the Trades Hall. The police haul netted, amongst others, Bill Andrews, George Mason, Ernest Shaw and some incriminating documents.

The striker commandos soon struck back. As the air force flew sorties from the Swartkops aerodrome over Benoni and Brakpan, Captain W. W. Carey-Thomas acting as observer on the DH9 aircraft piloted by Lieutenant C. J. Venter, was killed by ground fire.

The Brakpan striker commando attacked a small armed garrison at the offices of the Brakpan Mine, killing the Special Police Commander Lieutenant Brodigan, three Special Police members and four Mine Officials.

At Benoni, the police were besieged in their barracks in Bedford Avenue. A Transvaal Scottish contingent of 200 men were sent by special train to relieve them. At Vogelfontein Station, the police cautioned them that the line had been interfered with at Avenue Halt. As the train slowly approached the Dunswart Crossing at about 14h00, fifteen mounted men were seen galloping away. Four platoons immediately detrained to cover the train. At the Crossing, they came under fire and the remainder of the battalion rushed to assist. In the ensuing skirmish 12 members of the Transvaal Scottish were killed and 30 wounded.

On Saturday 11 March, the mayhem continued. The Langlaagte Police Station was surprised and captured with one constable killed and 18 taken prisoner. The Jeppe and Booysens Police Stations were besieged but managed to hold out.

Then the Imperial Light Horse (ILH) was caught napping. From the Drill Hall, the general mobilisation centre, recruits for the I.L.H. were sent to the Regimental Headquarters at Ellis Park. There they were hastily equipped and formed into dismounted squadrons. The choice of Ellis Park as the Regimental Headquarters was a grave mistake, for the exposed camp was on an old football field twenty feet below the surrounding roads. At 13h30 about 150 soldiers gathered on the field, their rifles stacked some distance away. Suddenly without warning, the Jeppe and Denver striker commandos having crept unnoticed behind a high hedge on the south-eastern perimeter, opened fire. Another body of strikers fired on the camp from houses along Park Lane overlooking the camp. In moments the I.L.H. lost 8 men killed and 15 wounded.

On Sunday 12 March, government forces were finally ready to take the offensive.

At 06h30 in Benoni, a combined military and police force under Lieutenant Colonel Burne linked up with the 1st SA Mounted Rifles and two police units, near the Indian and African townships. Advancing towards the town centre it came under heavy fire from the Dunswart Iron and Steel Works where a large force of strikers was ensconced. Using the sole cannon at their disposal the military dislodged the strikers, who then retreated eastwards. Burne pursued them along Main Reef Road, though sustaining heavy losses due to sniping from roadside gardens and roofs of nearby houses. By 12h30 the relieving forces had marched out of Benoni and an hour later occupied the Brakpan Mine. They then advanced through Brakpan, without opposition. By 14h30 Brakpan was in Van Deventer’s hands and the process of rounding up the strikers began. The revolt on the East Rand was for all practical purposes over.

A section of the Cape Times article

Simultaneously, an attacking force consisting of the Durban Light Infantry, Witwatersrand Rifles, Rand Light Infantry, Imperial Light Horse, Transvaal Sottish and SA Mounted Rifles advanced from Milner Park, due west towards the Brixton Ridge. From the corner of Jan Smuts Avenue and Empire Road, 13 pounder guns of the Transvaal Horse Artillery (THA) shelled the north-eastern ridge and the Cottesloe School, where a strong force of strikers had gathered.

A section of the Transvaal Scottish advanced on the left, parallel to the northern boundary of the Braamfontein cemetery. With the terrain offering little cover it ran into deadly concentrated fire. Shot at from the ridge, the Milner Park Junior School and a dilapidated cottage near the north-western corner of the cemetery, the Regiment in no time suffered 3 dead and 29 wounded.

Two companies of the Durban Light Infantry (DLI) approaching via the Johannesburg Country Club, relieved the police on the ridge without suffering any losses. The striker commandos demoralized by the advancing troops, shelling from the THA and bombing by the air force, either surrendered or fled. Some seventeen hundred prisoners were taken and sent to interim prison enclosures below. The casualties on both sides were temporarily buried at Milner Park.

Following this successful advance, Lieutenant Colonel Thackeray established his headquarters at the Johannesburg Country Club in preparation for attacking the striker stronghold at the Fordsburg Market Square.

Shortly after daybreak on Tuesday 14 March, a military aeroplane dropped thousands of pamphlets over Fordsburg, warning all well-disposed civilians to evacuate the area via the Fordsburg subway before 11h00. From there they would be taken to an emergency camp at Milner Park.

The assault was almost due to be launched when an envoy from the strikers’ headquarters reached General Beves asking for terms, only to be told to surrender unconditionally.

The attack was arranged to emanate from the north, north-east and east.

At 11h00, one field gun of the THA commenced firing from Sauer Street, its observer placed on the roof of The Corner House. The remaining two artillery pieces fired from Brixton Ridge, just above the Auckland Park Camp. For seventy minutes almost 140 shrapnel shells rained down on Fordsburg, until the order to cease fire was given for fear of injuring captive policemen held in the Market Square building.

The DLI having bivouacked in Brixton, advanced on Fordsburg from the north with the Transvaal Scottish approaching from the north-east. The left flank of the Transvaal Scottish linked up with the Lieutenant Colonel Godley’s force attacking from the south-east and south. Godley’s force, consisting of police and special police also had a Whippet tank, which however broke down in the Fordsburg Subway. The strikers nevertheless found its appearance very unnerving.

Whippet tank approaching Fordsburg

At about 12h30 elements of the DLI and Transvaal Scottish having captured the Fordsburg Railway Station were advancing on the square, east of the station. Approaching the square, they encountered heavy rifle fire from barricades across the major roads running west to east. Major Adams and Lieutenant Gregorowski of the Transvaal Scottish were both killed in Main Road (now Albertina Sisulu Street).

Changing tactics and infiltrating through adjoining private properties the DLI entered a bottle store with frosted windows directly opposite the square. Surreptitiously placing a Vickers machine gun in this shop, they commenced firing at point blank range at the surprised strikers. A massed bayonet charge then carried the square. Inside the Market Square building they found the bodies of Fisher and his aide Spendiff, both having apparently committed suicide. Also found in the building were policemen held captive there following the surrender of the Langlaagte Police Station.

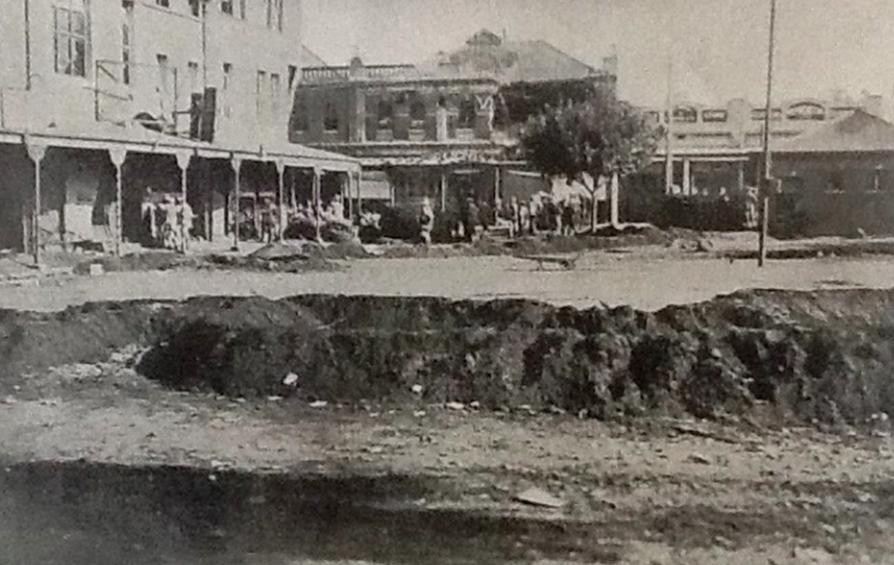

Fordsburg Market Square after the revolt. In the foreground the trenches dug around its edges and in the background McIntosh’s store damaged by artillery fire (Wikipedia).

By 14h00 the market square was secure and though sniping continued, the revolt was over. The captive strikers were marched off to the old Wanderers ground, next to the Johannesburg Railway Station. Here the thousands of strikers were screened and either formally charged and imprisoned or released.

During the next two days the ACF units fine combed Fordsburg, Brixton, Vrededorp, Turffontein and Rosettenville for revolutionaries and arms.

Unfortunate incidents occurred on 16 March, placing the Transvaal Scottish Regiment and government in poor light. W. E. Dowse, a member of the Rosettenville striker committee was arrested at his house for allegedly molesting Mrs. Adams, the wife of a scab worker. While taken to the Company headquarters of the Transvaal Scottish, Dowse allegedly tried to escape and was shot and killed by two soldiers.

Then the three Hanekom brothers and M. W. Smith were arrested by the Transvaal Scottish in connection with the cutting of telephone wires (which they admitted to but were forced to do so by the strikers) and concealing arms and ammunition (which they denied). They were taken down a secluded valley south of Rosettenville near Fouche’s Dairy to point out possible hidden arms caches. There all four were shot and killed while also allegedly trying to escape. There is a lingering suspicion this was in retaliation for the casualties suffered at the Dunswart Crossing and Brixton Ridge, although the subsequent commission of enquiry exonerated the regiment.

At midnight on 17 March 1922, the SAIF called the strike off. Strikers anxiously reported for work hoping to find out that their jobs had been held open for them. Many found themselves rejected because of their activities during the revolt. Almost 3000 mine workers were left unemployed due to a review of the mines’ labour force and their refusal to take back militant strikers. Even those who retained their jobs were subjected to lower earnings. In many ways this was a rather sad end to the strike, which started with so much hubris.

The government realising the prevailing legislation failed to effectively conciliate labour disputes, enacted the Industrial Conciliation Act, shortly prior to its defeat in the 1924 general election.

During this election, the opposition made great political play of Smuts’ hands supposedly dripping with blood following the violent suppression of this strike, the Bulhoek Massacre of the religious fanatics at Queenstown and the violent suppression of the Bondelswarts Rebellion in the then South West Africa.

The mine workers, deeply resenting the government’s handling of the strike, voted for either Barry Herzog’s National Party or Colonel Creswell’s Labour Party, who had entered into an election pact. The National Party won 63 seats (18 more than previously), the Labour Party increased from 9 to 18 with the South African Party obtaining merely 53 seats.

The subsequent Pact government created the Department of Labour in August 1924 to implement the provisions of the Industrial Conciliation Act. It also enacted the Mines and Works Act 25 of 1926 to reinforce the colour bar on the mines. Unfortunately for future race relations, this legislation remained in force for decades to come.

Click here to view surviving sites associated with the Rand Revolt.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

References

- Godley R. S. (1935). Khaki and Blue. Lovat Dickson & Thompson, London.

- Herd N. (1966). 1922 The Revolt on the Rand. Blue Crane Books, Johannesburg.

- Humphriss D. & Thomas D. G. (1968) Benoni Son of my Sorrow. Town Council of Benoni.

- Illsley J. (1989). Swartkop 1921 – 1986. SAAF Museum Publication.

- Juta H. C. (1933). The History of the Transvaal Scottish. Hortors Limited, Johannesburg.

- Kentridge M. (1959). I Recall. The Free Press Limited, Johannesburg.

- Klein H. (1969). Light Horse Cavalcade 1899–1961. Howard Timmins, Cape Town.

- Krikler J. (2005). The Rand Revolt. The 1922 insurrections and racial killing in South Africa. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

- Martin A. C. (1969). The Durban Light Infantry 1854–1960. Volume 1. The Headquarter Board of the Durban Light Infantry in co-operation with The Regimental Association.

- Oberholzer A. G. (1982). Die Mynwerkerstaking Witwatersrand 1922. RGN, Pretoria.

- Orpen N. (1975). The History of the Transvaal Horse Artillery 1904–1974. The Transvaal Horse Artillery Regimental Council, Johannesburg.

- Smith A. H. (1971). Johannesburg Street Names. Juta & Company, Johannesburg.

- The Johannesburg Historical Foundation. (Not dated). Some Historical Drives and Walks of Johannesburg. Framic Pty. Ltd., Johannesburg.

- The Star. (1922). Through the Red Revolt on the Rand. The Central News Agency Ltd.

- Van der Spuy K. (1966). Chasing the Wind. Books of Africa, Cape Town.

- Van der Waal G-M. (1987). From Mining Camp to Metropolis. Christo van Rensburg Publications (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg.

- Walker I. L. & Weinbren B. (1961). 2000 Casualties. South African Trade Union Council, Johannesburg.

- Walker M. (2013). The Pioneer Architects of Johannesburg. Privately published.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.